Unfettered Brush:

The Art and Writings of Tan Joo Jong

Published on the occasion of the exhibition:

Unfettered Brush:

The Art and Writings of Tan Joo Jong

Exhibition organised by NUS Museum, from 1 September 2024 to 30 June 2025.

Front Cover:

Tan Joo Jong, Bird and Lotus, 1980, Ink on paper, 68 x 46 cm

Back Cover:

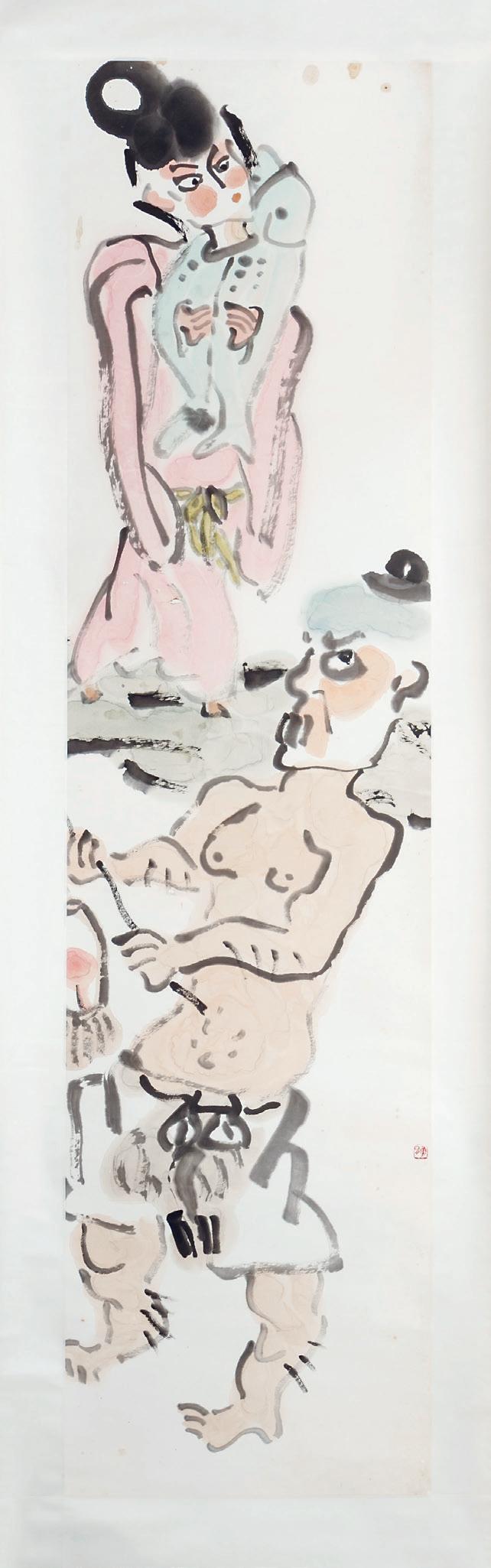

Tan Joo Jong, Opera Figures, circa 1977, Ink and colour on paper, 150 x 38 cm

Foreword

Ahmad Mashadi

University Curator

In 2013, NUS Museum held the exhibition, Between Here and Nanyang: Marco Hsu’s Brief History of Malayan Art, which explored the writings of art critic Marco Hsu. First published in the Nanfang Wanbao (Nanfang Evening Post), Hsu’s essays were later compiled into a book, A Brief History of Malayan Art. The series of articles aimed to chronicle and document the contemporary status of art in Malaya on the eve of Malaya’s independence. Written between 1961 and 1963 for a predominantly Chinese-educated audience, the articles charted cultural development against the backdrop of independence—a search and a proposition for a common ground that the Chinese-educated community might find, to stand with other ethnic communities for a shared future in the newly created nation-state.

Curator Chang Yueh Siang wrote, “This marked a shift from a Chinese person thinking about Malaya as ‘the Nanyang’, to considering a common cultural identity and future for the soon to be merged political entity of ‘Malaya’.”1 Importantly, Hsu’s essays provided a platform for younger artists2 to be featured publicly, introducing them as contributors to the cultural endeavour that was being undertaken. At the same time, discursively, young student artists were also participating in conversations about the social importance of art in these early years of the postwar movement towards independence. This can be seen in the essays written for an exhibition publication by “Chinese High Schools Graduates of 1953”3 (several of whom became members of the Equator Art Society), and those written by students from the Nanyang University (Nantah) Student Art Society in the 1960s.

This was the social and cultural milieu in which Tan Joo Jong was embedded when he embarked on his artistic journey as a student participating in the Nantah Student Art Society. From his personal artistic practice, Tan’s influence expanded

into the editorial sphere where he contributed to local art discourse as editor of the Educational Publications Bureau’s Singapore Art (1975–81) and, significantly, as arts editor of the Chinese daily Sin Chew Jit Poh (1979–83). He promoted artistic activities amongst various groups, particularly by giving generous coverage and reviews of many art exhibitions and events, but also through his official appointments and membership in art groups such as the Chinese YMCA Art Group, Hua Han Art Society and Modern Art Society.

Continuing from Marco Hsu’s ‘oasis’ (a metaphor for the flourishing postcolonial art scene), through his journalistic career (as well as his artistic practice), Tan played his part to cultivate the figurative land to foster a viable environment for local arts to thrive. By the 1980s, this vision for the arts had gone beyond a place of refreshment in a ‘desert’, and set its sights on a broader international and modernist horizon when Tan came together with several international artists to form the International Contemporary Ink Painting Movement.

The 1980s marked the burgeoning of the art scene in Singapore, which Tan Joo Jong covered as an editor. Unfettered Brush: The Art and Writings of Tan Joo Jong (made possible by a loan from a private collection) forms a cohesive link with research on the important contribution of press journalism to the arts, which began with our previous exhibition on Marco Hsu’s essays. With NUS Museum’s T.K. Sabapathy Collection (donated by the art historian who also wrote in the English-language press about contemporary artists beyond the Chinese-educated network), these projects allow NUS Museum to begin to trace a continuity in the development of a post-independence cultural history, and construct a map of the individuals and groups that laboured to establish a culture we can call our own.

1. Exhibition brochure, Between Here and Nanyang: Marco Hsu’s Brief History of Malayan Art, NUS Museum (21 August 2013–3 September 2016), p. 1.

2. Marco Hsu positioned these “vibrant young artists” into two groups: (1) practitioners who were usually academically trained in the Western media, and (2) those who contributed to the ‘Malayanisation’ of Chinese painting.

3. Special Issue for the Exhibition of 1953 High School Graduates, Singapore (1953). This exhibition took place in August 1953 and was held at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce before moving to the Hokkien Hoay Kuan.

Curator’s Introduction

Chang Yueh Siang Curator

Born in 1951, Tan Joo Jong (陈有勇) spent his early years in the postwar milieu where diverse cultural and ethnic considerations and propositions of a postcolonial national identity were forged. The 1950s saw the deliberation of Malayan independence, the debate of racial politics within government and on the ground, and the formulation of new language and educational policies. It is against this backdrop that the term ‘Malayanisation’ was coined to describe the search for native-grown culture in artistic and literary discourses.

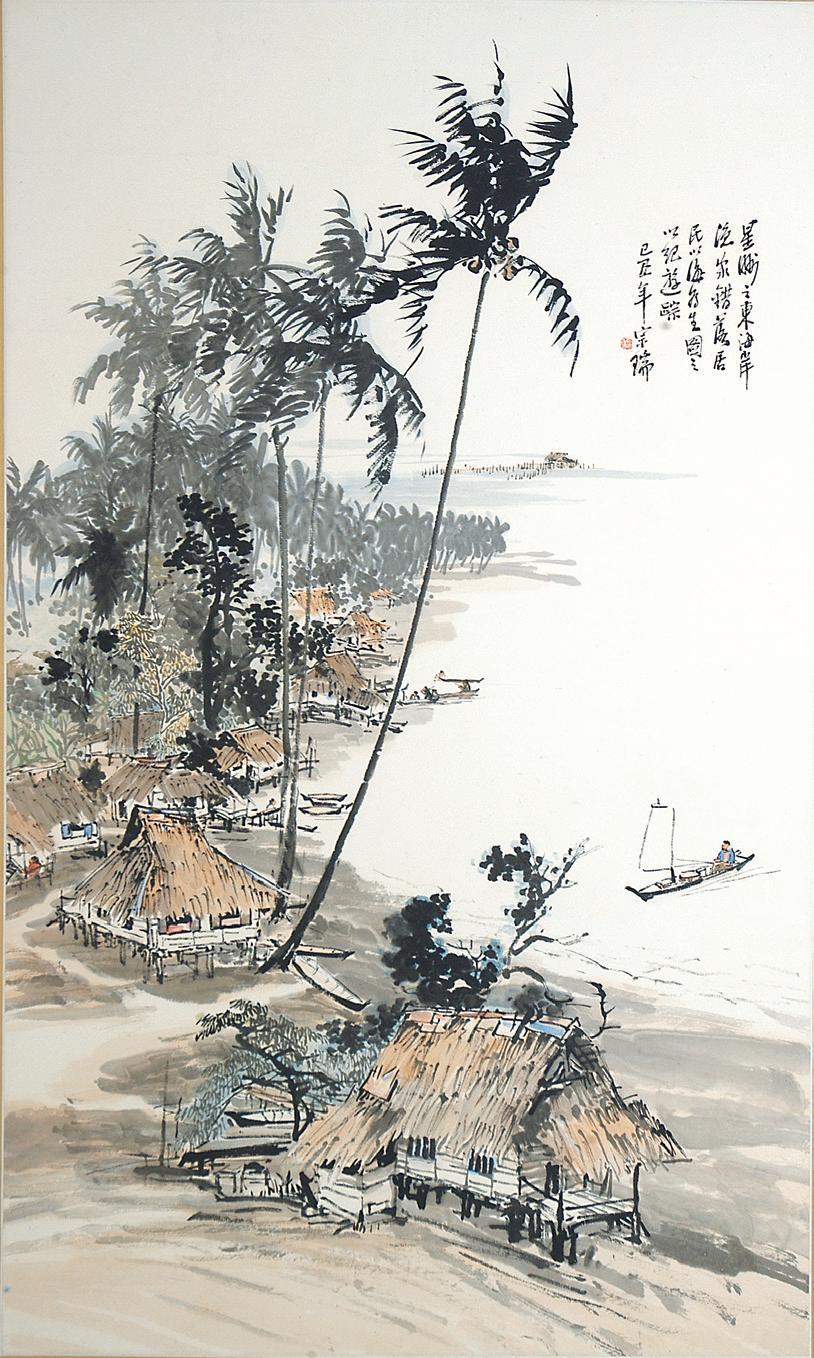

There is an apocryphal belief that the ‘Nanyang1 Style’ began with Chen Chong Swee (陈宗瑞), Chen Wen Hsi (陈文希), Cheong Soo Pieng (钟泗宾) and Liu Kang’s (刘 抗) visit to Bali in 1952.2 However, one might consider the proposal that what is today identified as Nanyang Style was the product of Malayanisation: “Nanyang Style — this is actually a Malayan style. Malaya is already on the path towards independence; it can’t not have its national style. This national style is tropical in nature, melding the artistic styles of the four people groups—Chinese, Malay, English, Indian—in a crucible. Only by allowing them to blend can a Nanyang style of art come about.”3

To simplify the diverse cultural activities of this period into schools or styles of art is to reduce the complexities of identity formation into diluted parts. Certainly, for urban artists (who were often from Chinese-language backgrounds with little interaction with other ethnic communities), the turn of the

artist’s gaze towards the local initially yielded romanticised images of idyllic kampongs or coastal fishing activities.

One of Tan’s earliest works, Changi Village (1972), perhaps, understandably, followed the conventions of this time, and would not have looked out of place alongside the works produced by his contemporaries. But these depictions were not always corroborated by other artists or writers4 whose observations were of rural or suburban poverty, and neither were these a mere question of aesthetic choice—words were staked on the morality of the choice of subject matter and artistic styles. (For example, essays in the Special Issue for the Exhibition of 1953 High School Graduates speak of the importance of establishing a “correct” Malayan culture;5 and caution against blindly accepting the “innovations” of artists such as Picasso, or styles like Fauvism. These artistic styles were perceived as indulgent and decadent—influences introduced by the “capitalist imperialist” colonisers to lull the people of Malaya into a continued stupored acceptance of subordination.6

What this discourse belies, however, was that artists were attempting to discover or define a local visual and cultural language that would be representative of nascent Malayan identity. This culminated in Ho Ho Ying’s (何和应) articulation to the Nanyang University (Nantah) Student Art Society that “our basis for Malayan art is not limited to kampong attap houses, sarongs, Malay fishing villages, etc. All new types of art created by Malayans are within our scope”.7

1. The term ‘Nanyang’ (translated literally as ‘Southern Seas’) was historically used by mainland Chinese seafarers and Chinese populations migrating by sea as a geographical term to denote the region today identified as Southeast Asia.

2. Marco Hsu ( 玛戈) was one of the first who published this attribution, in the essays anthologised in A Brief History of Malayan Art《马来亚艺术 简史》 .

3. San Wu (三无), “On the Nanyang Spirit”, in Yearbook of the 15th Cohort of Graduates from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts《南洋美专第十五 届毕业特刊》, 1955.

4. Such as A. Samad Said in his novel Salina (1961), or Han Suyin in And the Rain My Drink (1956).

5. A Xi, “The United Artistic Front Must Be Purged of Formalism,” p. 3.

6. Li Tianming, “Three Objections to Pablo Picasso: Formalistic Art is Degenerate Art”, p. 5.

7. Ho Ho Ying, “A Word from the President”, in Nanyang University Arts Society Exhibition, 1961, p. 2.

Chen Chong Swee, Kampong, 1949, Chinese ink and colour on paper, 114.3 x 68.5 cm. S1956-0015-001-0

Foo Chee San, Kampong in Pasir Panjang, 1965, Woodblock print, 57 x 38 cm. S1999-0016-005-0

Tan Joo Jong, Changi Village, 1972, Oil on board, 61 x 92 cm

Nanyang University 8

By all accounts, Tan did not receive formal art training, but showed interest and aptitude as a student in the art curriculum at Anglican High School which he attended from 1964 to 1969. Outside of school, he sought out teachers and artists for advice, but more significant to his early practice was his habit of sketching landscapes, and experimentation.9 Tan was to have gone to Australia on a Colombo Plan scholarship,10 but administrative changes led to his matriculation into Nanyang University (Nantah) in 1969, where he joined the Nantah Student Art Society. Here, Tan’s artistic inclination was nurtured, and he blossomed.

Art critic Marco Hsu, in A Brief History of Malayan Art, noted: “The situation of student-led study and practice of art is stronger at the Nanyang University than at the University of Singapore.”11 Over the years, the Nantah Student Art Society produced a distinguished alumni of artists and cultural catalysts such as Ho Ho Ying, Ho Kah Leong (何家 良), Tan Swie Hian (陈瑞献) and others.

Tan Joo Jong’s membership in the society shaped him in several ways. Firstly, it allowed Tan to experience the camaraderie of working as a collective. In the catalogue of the first exhibition that Tan participated in (the 10th Annual Exhibition organised by the Art Society since its inauguration in 1961), then President of the Society Ma Poh How (马波浩) gave a glimpse of the wide range of activities undertaken by the Art Society:

The Exhibition is not the entirety of what we do as an Art Society, but it is one of the most important… Apart from after-school activities such as still-life sessions, research, talks and seminars, we also do what we can to provide our services to the University and other campus communities. The banners, cartoons, posters and slogans for festive ceremonies and other group events… many of these were designed by us. Many publication covers, invitations and newsletters were also designed by us.12

8. A part of the NUS Museum collection originated from the Lee Kong Chian Museum that was established at the Nanyang University in 1970.

9. In this, Tan’s early experience in self-learning is similar to that of the artist Ng Eng Teng, for whom the gallery in which this exhibition is situated is named.

10. Conversation with Mrs Tan Joo Jong, 31 May 2024.

11. Marco Hsu, “Chapter 18: From Desert to Oasis”, A Brief History of Malayan Art, 1963.

12. Ma Poh How, “From the President”, Nanyang University Student Art Society’s 10th Exhibition Special Issue (1970), p. 4. The essay also lists the challenges of motivating and mobilising members to take more initiative to play their role within the organisation.

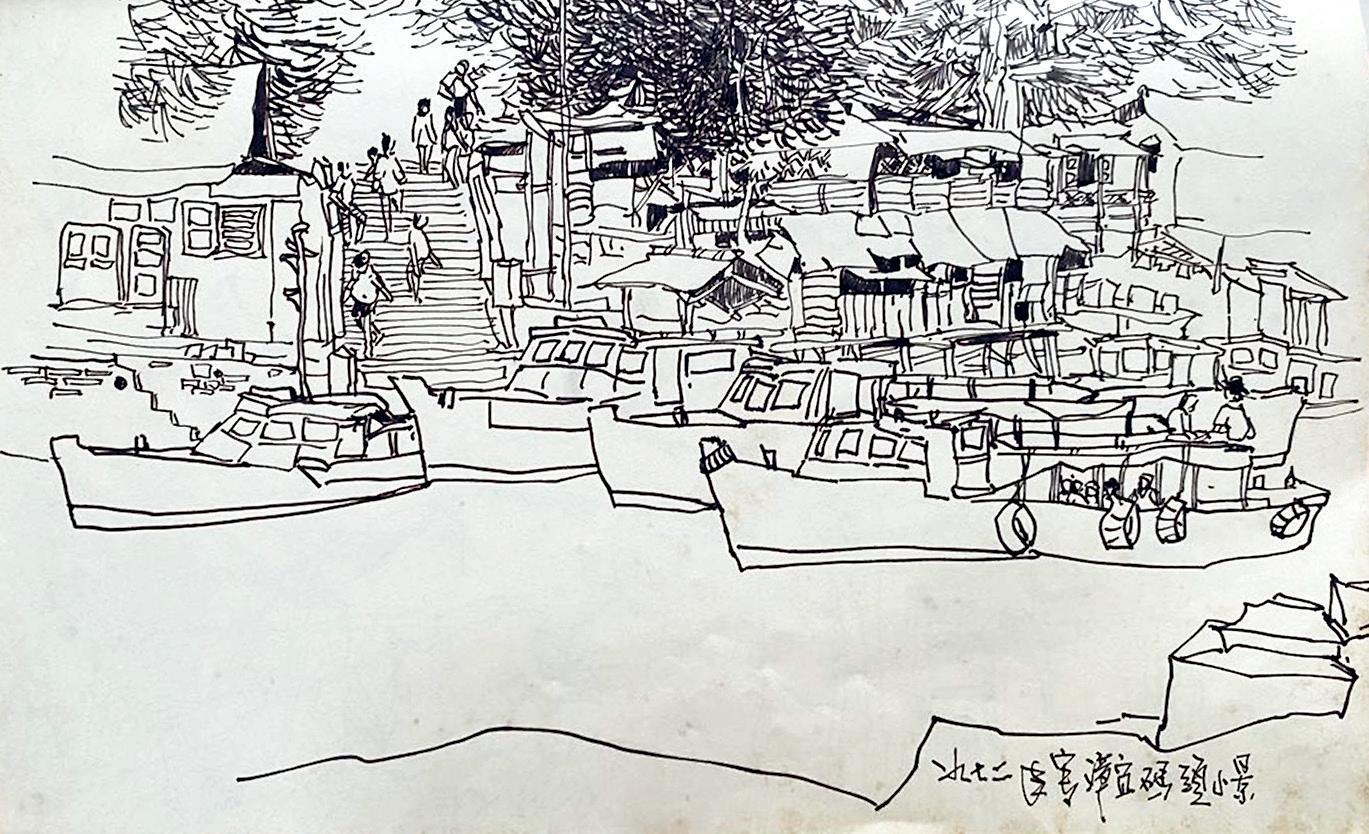

Tan Joo Jong, Sketch of Changi Point Jetty, 1972

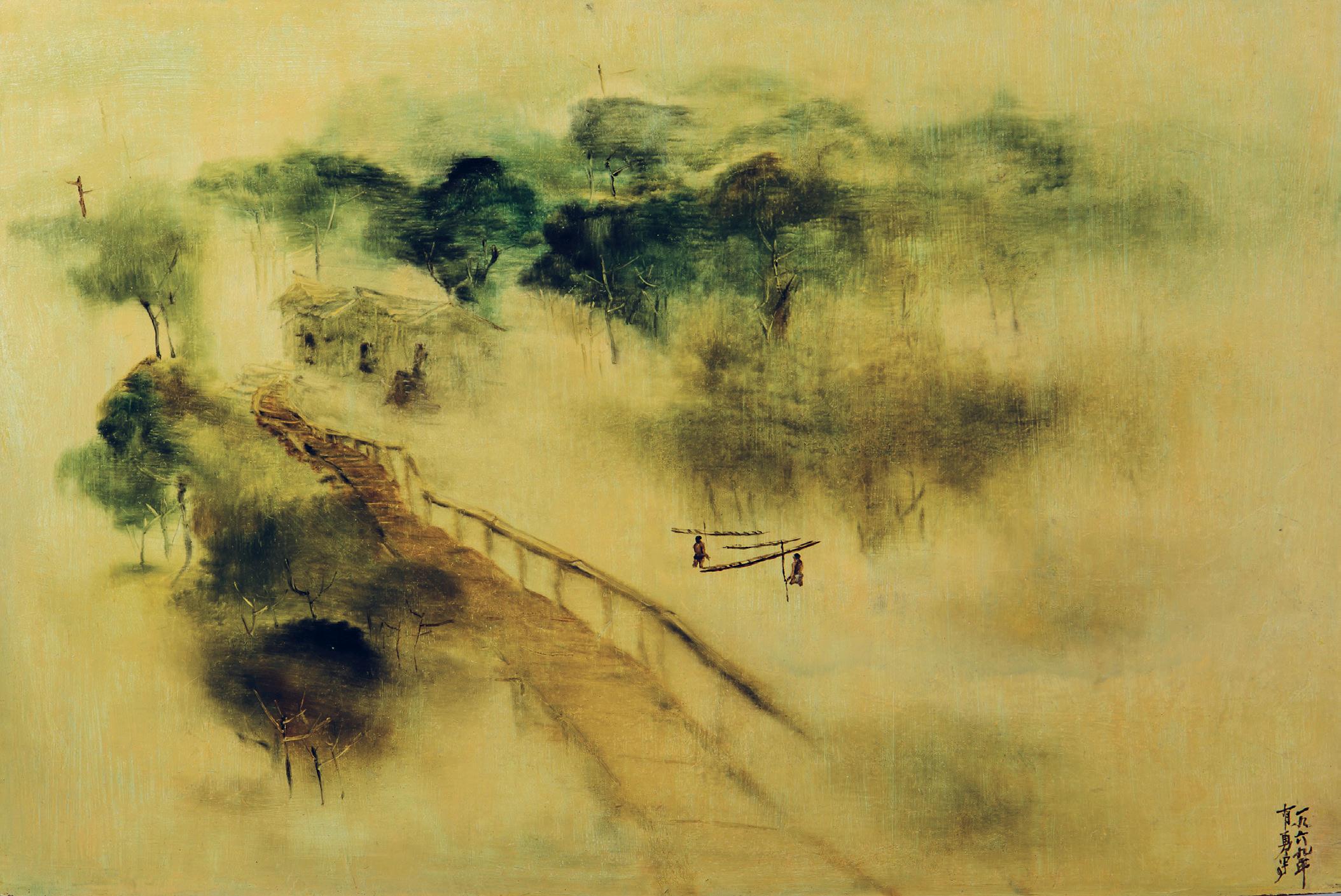

Tan Joo Jong, Bridge Over a Running Creek (小桥流水人家), 1969, Oil on board, 61 x 92 cm

Tan’s deep involvement in the Society’s activities produced a momentum that he sustained post-graduation, participating in various art associations and exhibitions. These included the Nantah Graduates (Alumni) series of exhibitions, as well as the Singapore Art Society, Modern Art Society, Hua Han Art Society, Chinese YMCA Art Club and others.

The Nantah Student Art Society offered an intellectually and artistically open space where students were free to experiment and express themselves using different styles, media and techniques. Nestled in such an environment, Tan could now stretch his artistic curiosity.

In his aforementioned first exhibition, Tan presented an oil painting on board, Bridge Over a Running Creek (小桥流水人家, 1969). Apart from this work and another painted in the same year, and Changi Village painted in 1972, there appear to be few known completed artworks made

in the early years of his student life (1970–72). Rather, Tan carried a sketchbook with him at all times, and produced copious amounts of sketches as part of his emerging personal practice. These sketches became the foundation that underpinned the paintings he created between 1973 and 1975.

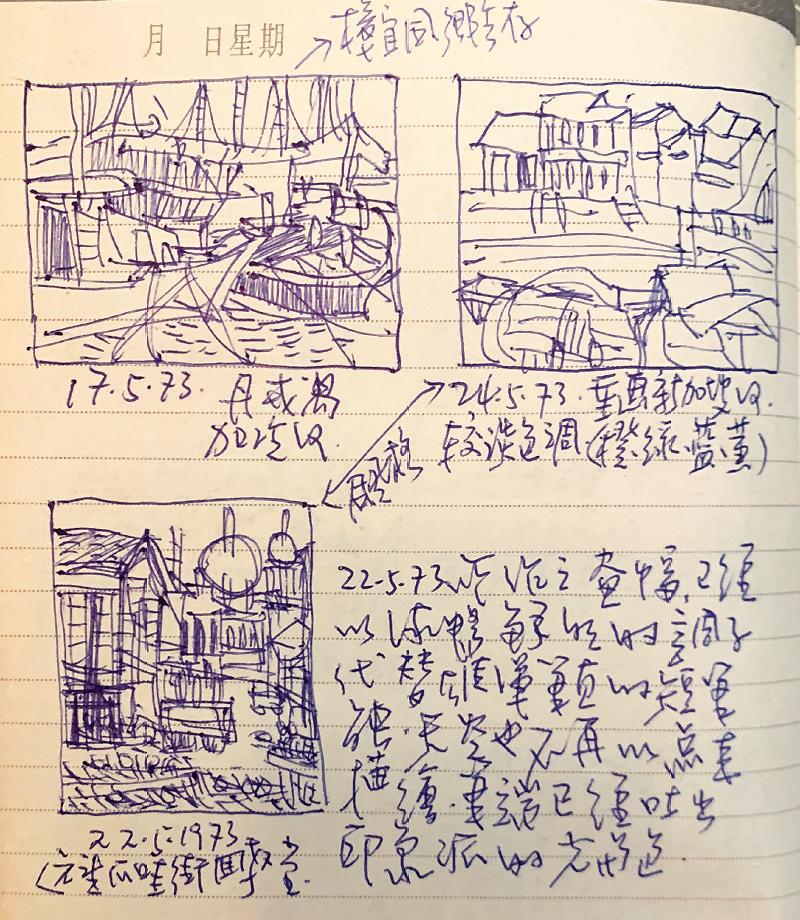

The media and techniques that Tan primarily experimented with during this period drew from Western traditions: oil and gouache on board or paper. His diary entries from 1972 to 1973 reveal his reflections, as well as his references— modern masters such as Picasso, Matisse, van Gogh, among others. From the personal materials available to us, this gradual development from drawing to committing colours onto board or canvas would appear to have been an intentional process of systematically layering up from technical foundations.

Diary entry showing sketch of Kampong Java dated 22 May 1973

Tan Joo Jong, Untitled (Kampong Java), circa 1973, Oil on board, 61 x 49 cm

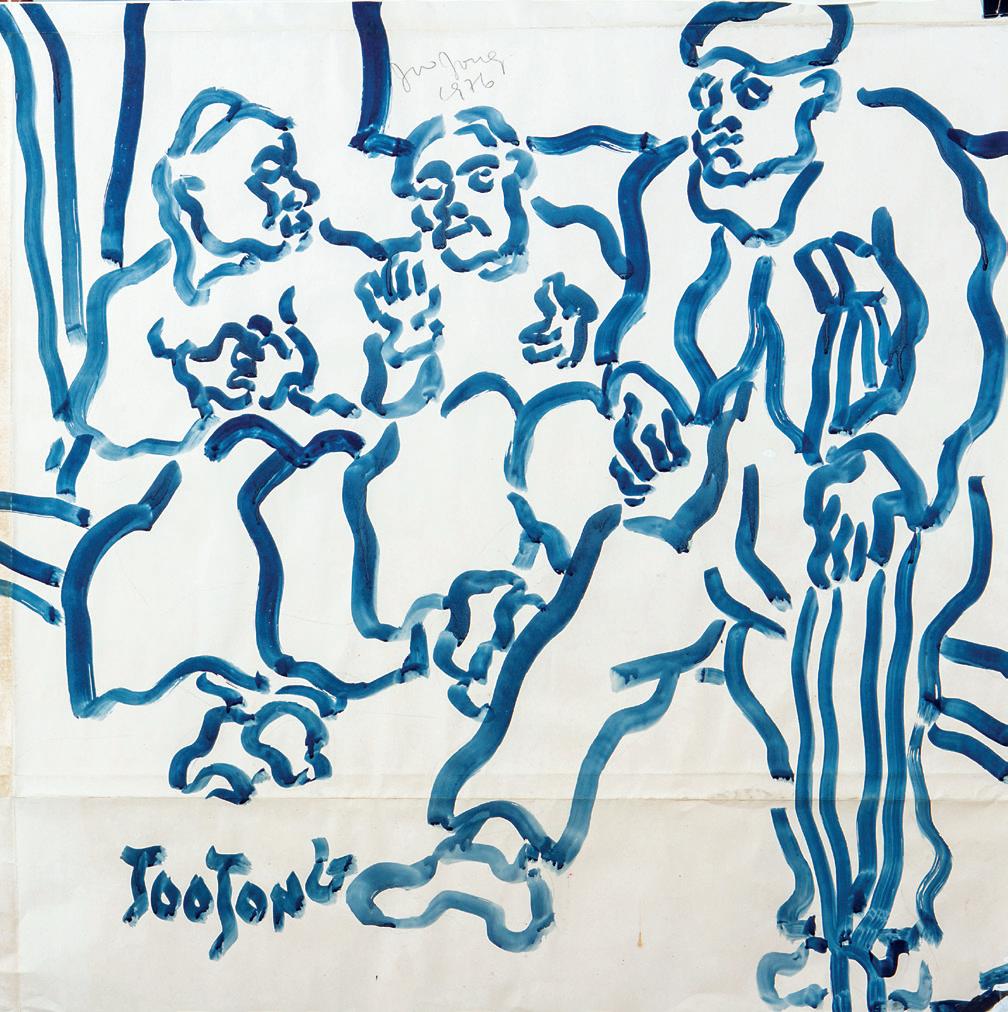

Tan Joo Jong, Untitled (Man with Crutches), circa 1976, Gouache on paper, 80.5 x 86.5 cm

Untitled (Man with Crutches), 1976, Gouache on paper, 61 x 51 cm

The Turn to Ink

From the exhibition publications produced by the Nantah Student Art Society, it is apparent that “all new forms of art created by Malayans [and by extension Singaporeans]”13 spanning media as diverse as oil, batik and Chinese ink— were practised and welcomed. Tan had had some exposure to Chinese ink before Nantah,14 and would have had exchanges with schoolmates who worked with ink. This background informed his turn towards Chinese ink circa 1975.

This transition also largely arose from practical considerations. After enlisting in National Service, Tan was posted to Tengah Air Base and was able to book out daily. Not wishing to waste a moment for painting, he rented a room near Yunnan Gardens (not far from the Nanyang University campus) so that he could practise daily. Under these domestic arrangements, it was impracticable to store canvases or use turpentine. As a result, he made the shift to Chinese ink as the implements for the medium were more portable.15

Some observers have said that the brush lines in Tan’s Chinese ink works were a continuity from the lines and strokes of his Western techniques. One of Tan’s early ink works, Kingfisher and Reed (1970), does appear to indicate

observation and draughtsmanship that relate to techniques in the Western tradition. While there may initially have been some apparent continuities, these were soon moulted as Tan went voraciously into the research and practice of ink.

Reminiscent of the period when he focused on sketching, he made sure to also ground himself in the fundamentals. Soon after turning to ink, his diary entry of 30 May 1976 indicated that he had visited See Hiang To (Shi Xiang Tuo, 施香沱) in March “to study calligraphy”, and that Yeh Chi Wei (叶之威) had encouraged him to research rubbings of stone carvings and inscriptions.16

Much of his exploration in ink was autodidactic, which he might have been self-conscious about. He later made it a point to note that he had been “much encouraged” by the words of artist-teacher Fan Chang Tien (范昌乾):

In the few years we were at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, we did not learn much (foundational techniques at best). What is more important is to feel your way by yourself. I relied on a few boxes of art books. Western artists do the same, as do Chinese ink painters.17

13. Ho, “A Word from the President”, p. 2.

14. The Chinese-ink painter Chen Wu Chi ( 陈悟迟, Tan Seng Yong) was an art teacher at Anglican High School, and Tan had exchanges with him during this period. Conversation with Mrs Tan Joo Jong, 13 May 2024.

15. Ibid.

16. See Hiang To, an ink master famous for his painting, calligraphy and seal-carving, is known to meticulously train his students to start with studies of different calligraphic scripts according to the chronology of Chinese writing.

17. Tan Joo Jong, diary entry, 28 September 1977.

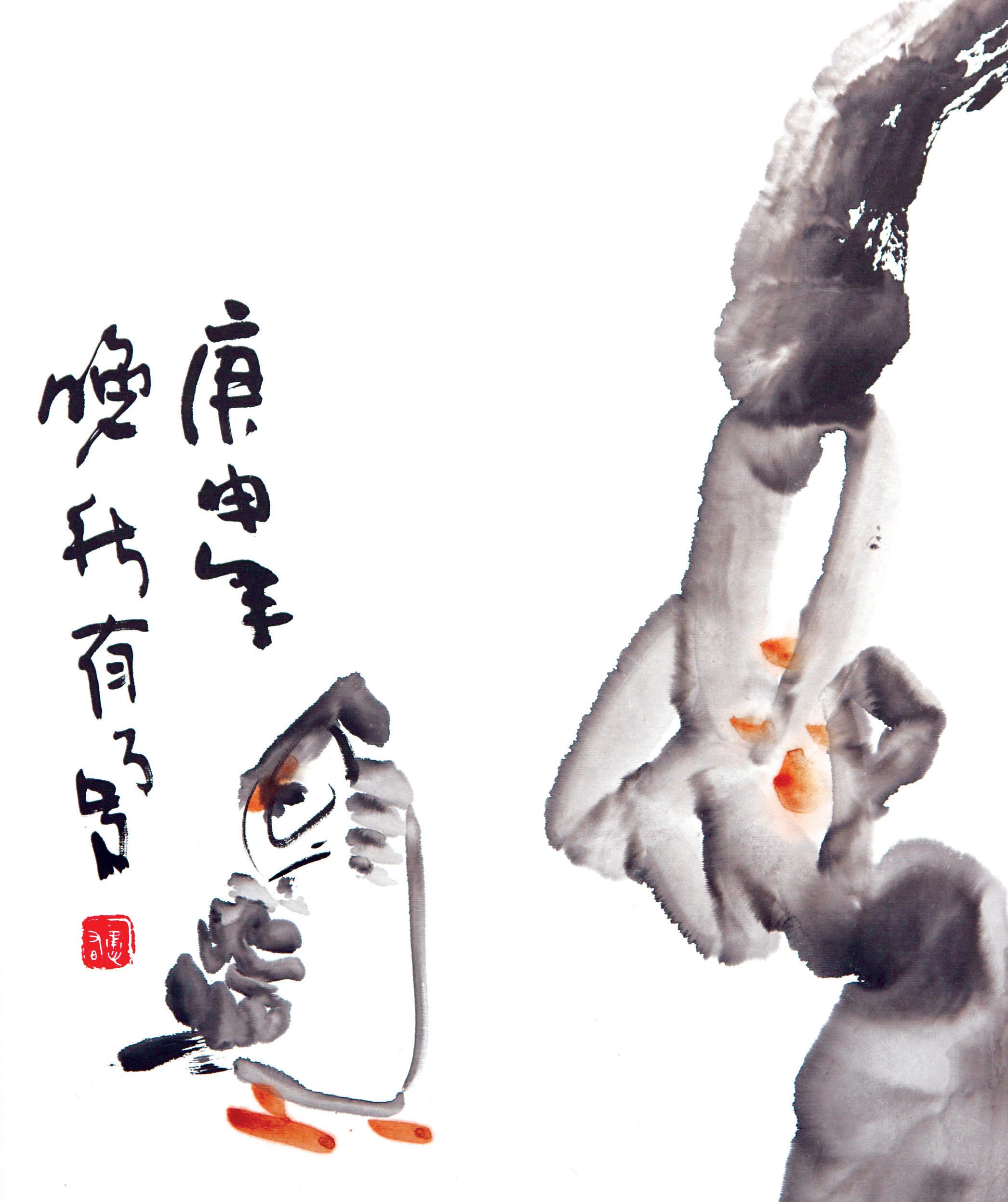

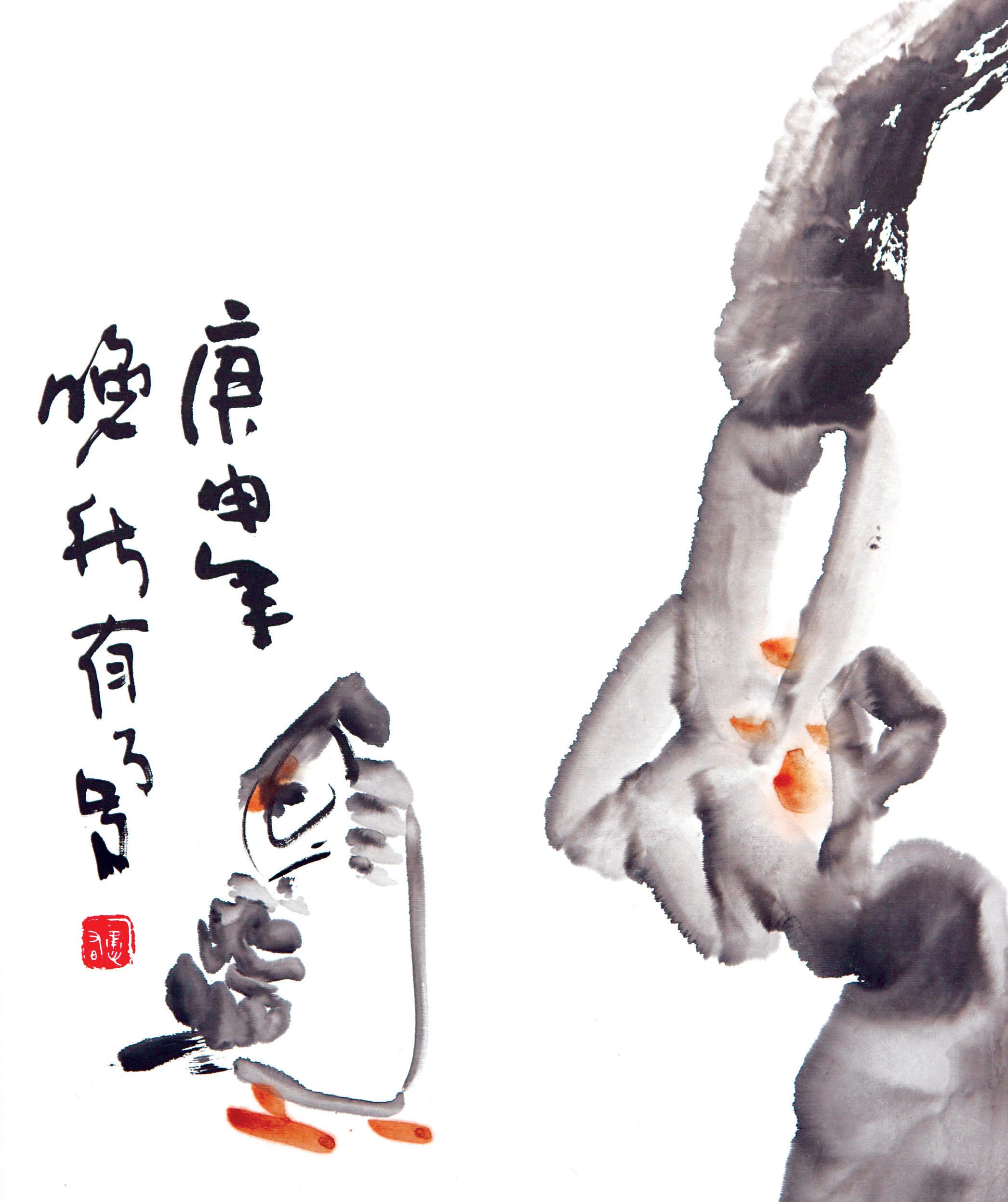

Tan Joo Jong, Kingfisher and Reed, 1970, 庚戌年, Ink and colour on paper, 74 x 32.5 cm

Proliferation of Art Discourse

This brings us to the second way in which the Nantah Student Art Society shaped Tan’s emerging practice: it formed the soil that germinated in him the seeds of intellectual discourse about art theory and practice, which provided a good foundation for his self-learning.

From its founding, art discourse had been a key aspect of the Society’s tradition. Earlier members such as Tan Swie Hian and Ho Kah Leong went on to play significant roles in the promulgation of art discourse in Singapore. Tan Swie Hian was part of the editorial team of a number of art-related publications including the cultural magazine Chao Foon (蕉风, Jiaofeng), while Ho established the Educational Publications Bureau which published the landmark 17-volume Singapore Art (新加坡美术, 1975–81). Each volume of Singapore Art was replete with essays by well-known artists, art teachers and commentators. Tan Joo Jong was the editor for the volumes published between 1976 and 1979, and Marco Hsu was a regular contributor.

The special issue that accompanied the Society’s inaugural exhibition in 1961 contained essays and commentaries on art, such as Chuah Thean Teng’s (蔡天定) writing on batik, and a piece on Chinese ink by renowned academic and calligraphy Professor Liu Tai Xi (刘太稀). The following year, led by Ho Kah Leong (Vice-President to Ho Ho Ying), the

Society launched the periodical, Fine Arts, with the hope that “art may truly serve the people” and to provide a platform for artists to establish a system of art theory that would guide artistic development in Singapore and Malaysia.18 Although this publication did not continue after the first issue, it can be said to be the precursor of Singapore Art

Not one to do things by halves, Tan read and studied intensively as he painted. He referenced as many artists as he could, though was particularly enamoured by Bada Shanren (八大山人), Guan Liang (关良) and Ding Yanyong (丁衍庸). His journalistic writings about ink and art in the late 1970s and early 1980s mirrored his artistic development.19

He wrote about Chinese ink, even drawing on classical texts and philosophies, but not in a way to insist on ink as a traditional, Chinese cultural canon.20 For Tan, an overemphasis on orthodoxy and technical accuracy itself was a type of ‘realistic formalism’, focused on technical mastery and lacking creative expression.21 In this, Tan understood formalism differently from the earlier student artists among the aforementioned 1953 High School Graduates. The latter condemned artists such as Picasso and Matisse for indulging in form (appearance) and feelings over moral content, and advocated realistic portrayal in both subject matter and the medium of representation.22

18. Ho Kah Leong, “Inaugural Foreword”, Fine Arts (Vol. 1), The Student Arts Society, Nanyang University, 1962, p. 1. There does not appear to be subsequent issues of this periodical published by the Art Society.

19. A selection of essays penned by him will be included in a publication that is being produced on the occasion of this exhibition.

20. One is reminded of Culture Minister Jek Yeun Thong’s exhortation on the occasion of the opening of the Nantah Lee Kong Chian Museum in 1972, that Singapore must not think of itself, and its culture, as a dependency of China. The Bulletin of Nanyang University, vol. 2, no. 30, August 1972, p. 6.

21. For example, Tan compares the technical mastery of Giuseppe Castiglione’s realist gongbi technique with Qi Baishi’s expressive xieyi technique, and Picasso’s freehand sketches with da Vinci’s anatomical sketches, to make the point that heavy emphasis on technique places restraint on spontaneous artistic expressions. Tan Joo Jong, “On Modern Art”, Singapore Art, vol. 3, Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau, May 1976, p. 8.

22. A Xi, “How to Learn to Draw”, Special Issue for the Exhibition of 1953 High School Graduates, p. 7.

As Tan saw it, all traditional art forms (such as painting and sculpture) are conveyed by lines and strokes;23 form and colour were vehicles for carrying the underlying emotions of art.24 He came to see ink as a way to excavate the implications and applications of the principles of art: “East Asian ink art… is unconstrained by time and space. It is an expression of traditional techniques, but also encompasses the spirit of the times. If artists of the East are able to wield ink in their creation, that would be leading the way for our times.”25

In his own practice, he emulated the minimalist lines of Bada Shanren,26 the expressiveness of Guan Liang in conveying the emotions of operatic characters, and the modern ‘eccentricism’ of Ding Yanyong—features that are particularly prominent in Tan’s Balinese landscapes from the 1980s. These landscapes were beyond Western ‘types’, Chinese composition or rural clichés (kampongs, fishing villages), but found new expressions through the essential lines and strokes from Tan’s brush.

23. Ibid., p. 9.

24. Ibid., p. 8.

25. Tan Joo Jong, “A discussion on the question of ink painting from classical texts and the philosophy of Zhuangzi” (Part 2) (从古文与 莊学再谈水墨画的几个问题 – 下 ), 南洋商报 (Nanyang Siang Pau), 7 February 1979, p. 27.

26. Tan Joo Jong, “Approaching Modern Chinese Ink Art through Guan Liang”, Singapore Art, vol. 8, Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau, July 1977, p. 35.

Tan Joo Jong, Urban Landscape, 1976, 丙辰年, Ink and colour on paper, 137 x 33.7 cm

Towards Professionalism

What is not evident in Tan’s individual practice is the extent of work he was also doing as a member of different art groups. Not only was he participating in exhibitions as a member (Singapore Art Society and Singapore Society of Chinese Artists, 1975–76), he also held official titles in various art groups (Secretary, Chinese YMCA Art Club, 1975–76; Secretary, Hua Han Art Society, 1979; Secretary, Modern Art Society, 1982; President, Hua Han Art Society, 1983).

Concurrently, he was one of the editors of Singapore Art (1975–79) and the art editor of Chinese daily Sin Chew Jit Poh. In the latter capacity, he devoted columns and pages to the coverage of local exhibitions, particularly of the different art groups, highlighting individual artists, not only to publicise them, but to review them as well. He interviewed, and reviewed, eminent artists such as Zao Wou-Ki (赵无 极), Guan Liang, Doyo Prawito and Shen Yao Chu (沈耀 初). There is much more research that can be undertaken to illuminate the relationships between the artists, and how these activities shaped the cultural milieu in Singapore, even before the government put in place the Renaissance City Plan from 2000 to 2012 to develop the arts in Singapore.

Finally, Tan’s influence expanded beyond his artistic practice as he promoted local art in his capacity as a journalist. In his career and practice, Tan not only contributed to developing an artistic vernacular; he looked towards grafting artistic practices in Singapore onto a larger plane. In 1982, he was one of the founding members of the International Contemporary Ink Painting Movement27 (other founding members included Singapore’s Chen Wen Hsi, Chung Chen Sun (Zhong Zhengshan, 钟正山) from Malaysia, Wucius Wong (王无邪) from Hong Kong, David Kwo (郭大维) from the USA, and representation from Taiwan and South Korea).

Tan's eclectic approach to art appears to have been informed by the range of discussions and practice in Singapore art The landscape that Tan left behind, which he had cultivated alongside other artists of his generation, created the conditions for a locally grown cultural scene beyond the ‘oasis’ that Marco Hsu described at the end of his essay in 1963. The ‘land’ was potentially ‘fertile’, responsive to cultivation and nurturing, but Tan’s aspirations for art (and the ink medium that he came to embrace) went beyond local boundaries: “If artists of the East are able to wield ink in their creation, that would be leading the way for our times.”28

27. This organisation is still active today.

28. Tan, 7 Feb 1979, p. 27.

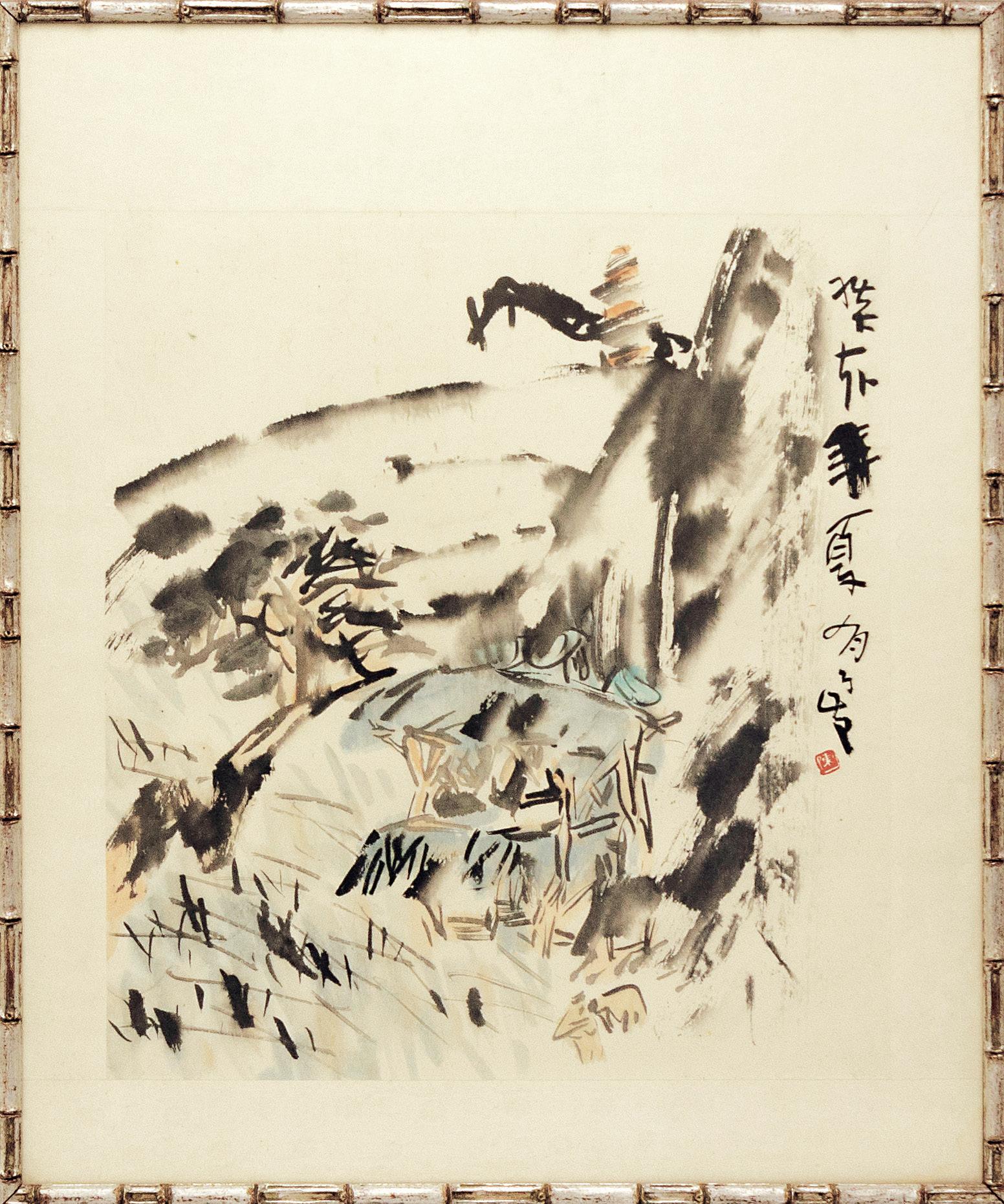

Tan Joo Jong, Bali Landscape, 1983, 癸亥年, Ink on paper, 58 x 52 cm

陈有勇文选摘录

EXCERPTS FROM TAN JOO JONG’S WRITINGS

1. 从古文与庄学 再谈水墨画的几个问题

在世界艺术史中,很少有像东方艺术那样,把文学、道德、 科学都包含在整个艺术文化系统中。而它的艺术自觉性, 又比西方艺术早了一千多年。「玄」学的启发,导致中国 艺术的真正自觉,毕竟中国艺术家所把握的艺术精神与境 界,都可说是心灵上的境界;他们所走的方向,是与西方 征服自然为己用的相反方向。梵谷在画布上激情的画上一 笔,引起了西方艺术家在精神上的某些自觉,以后的野兽 主义,表现主义,及立体主义在某个程度上来说,皆源於 此。然人与自然的亲和关系,主客合一的精神状态,唯有在 东方艺术里,不假藉宗教、神话及其他一切的力量,而能 真正地面对人性的根源,解决人类自身的问题以及因艺术 思潮而来可能发生的艺术危机。关於东西方艺术的问题, 笔者不在这里作深入的讨论,就以上的概念,作为东方艺术 为主体的文人水墨画及其与文学的结合发展,足以代表东方 艺术的某些精神实质,就这一点来讨论水墨画的几个问题。

在宋之前,「画无常工,以似为工,学无常师,以真为 师」几乎支配中国画坛的一般论调,必须指出的是,写 实是锻练艺术技巧的一种过程,而不是艺术之所以为艺 术的本质所在。中国艺术精神的本质,是由老莊,魏晋 玄学所开启而着落於水墨艺术的表现上。「形」也不为 人之所以为人的本质德性,亦不为人之「真」。只有深 入形之内部,才能把握其「神」而以神为物之「真」, 明乎此,才能了解文人水墨画的基木性格。董其昌在画 旨敍述得最为精僻:「看得熟自然传神。传神必以形。 形与心手相凑而相忘,神之所在也。」而莊子之所以 不以形为人之真,而以德为人之真的原因也就在此。 (上)

东方水墨画,是从人性的根源为出发点,以人格、学问、才 情和思想为其画格的依据。它和一般艺术的不同点乃在於它 所把握的是艺术的「全」,而一般艺术所把握的是艺术的「 偏]。水墨画之体现「为艺术而艺术」的信念,乃是以道德 人性,实际之生活来完成的,故其创艺之思想与情操和一般 艺术之所谓「为艺术而艺术」的信念,在本质上是完全不同 的。

东方水墨画因为恢复了它的自由解放性格,不囿於传统的艺 术观,似乎是抛开了人伦、政治、宗教与社会而建立其独尊 的地位。然正因为如此,它才能得与整个时代潮流相结合, 而发挥其无所为而无所不为的性格。它因为脱离某一文化项 目的束缚,而与整个文化、整个社会面相接触,甚至於人类 的心灵、本体和宇宙观。

东方水墨艺术在表面上看,似乎只是抒写心象,遗兴寄恨, 然它的内蕴力量实在是积极的,是整个民族经年累月历练发 展出来的结果,具有高傲的自尊和遥远的精神,不受时空的 限制,即能发挥传统技巧,又具时代精神。在未来的年代 里,东方艺术家如果能有所创作的话,我敢说那将是走在时 代的前锋。(下)

● (上篇1979年2月2日刊于《南洋商报》, 18页; 下篇1979年 2月7日刊于《南洋商报》, 27页. 新报业媒体有限公司版权所 有,复制需经许可。)

1. Re-examining Several Aspects of Ink Painting Through Classical Texts and Zhuangzi's Thought

As a cultural system that incorporates literature, ethics and science, Eastern art is distinctive in world art history. Its cultural awakening predates Western art by more than a millennium. The study of Xuan philosophy (Xuanxue, or Neo-Daoism) led to a true awakening of Chinese art. After all, the artistic domain held by Chinese artists can be said to be a spiritual realm. Their trajectory contrasts with that of artists from the West, which is one that conquered nature for one’s own use. It was van Gogh’s passionate brushstrokes on canvas that had roused the spiritual awakening of Western artists, and the subsequent styles of Fauvism, Expressionism and Cubism originated from this, to some extent. However, the affinity between humankind and nature, and the spiritual state of unity between subject and object, can only be found in the art of the East that does not resort to religion, mythology and external forces, but rather truly addresses the fundamental nature of humanity in order to resolve human problems, as well as the crises that may arise with the various waves of artistic thought. I will not discuss the problems of the art of East and West in detail here. Rather, the preceding concepts allow us to review the unified development of literati painting (the mainstay of Eastern art) with literature, as representations of certain spiritual essences of Eastern art.

Before the Song dynasty, the saying that practically dominated Chinese art discourse was, “There is no standard method in art but to seek resemblance; there is no teacher in this learning but Truth as the teacher.” It must be pointed out that realism is but a process in the honing of artistic techniques, and not the substance that makes art what it is. The essence of the Chinese artistic spirit was initiated by the philosophies of Laozi and Zhuangzi as well as the study of Neo-Daoism from the Wei and Jin periods, and found its expression in ink painting. ‘Appearance’ does not assume the moral nature of humanity, neither is it the ‘true nature’ of the individual. Only by delving deep beneath the surface of appearances can the artist grasp the ‘spirit’, and identify this spirit as the ‘truth’ of the object. Only when one has understood this, can one begin to understand the fundamental character of literati ink painting. Dong Qichang described this most incisively in his discourse on Chinese landscape paintings in Hua Zhi (Principles of Painting): “Familiarity by observation naturally translates into lifelikeness, which is expressed through form; when form, mind and hand converge without second thought, the essence of the subject matter is achieved.” This is also the reason why Zhuangzi did not consider appearances to be indicative of the true nature of a person, but rather regarded virtue as the integrity of a person. (Part 1)

Originating from human nature, Eastern ink painting justifies itself on the basis of personal character, knowledge, talent and thought. Where it differs from other forms of art is that it contains the ‘whole’ of art, contrasting with the ‘parts’ held by other art forms. The notion of ‘art for art’s sake’ as embodied in ink painting finds its fulfilment from a moral character and a life of practice. Therefore its creative thinking and sentiments differ qualitatively from the idea of ‘art for art’s sake’ found in art in general.

Having recovered its freedom of spirit, Eastern ink painting has liberated itself from the confines of conventional artistry, as if to abandon the order of human relationships, politics, religion and society, so as to establish its supremacy. However, it is precisely because of this that it can achieve unity with the trends of time, and express its characteristic of ‘doing nothing, yet accomplishing everything’. Since it is free from the confines of any particular aspects of culture, it engages entire cultures and societies, and even the human mind, matter and universe.

On the surface, Eastern ink painting may appear only to be sentimental expressions of the images of the mind, indulging the passions. Yet the innate strength is a positive one: it is the result of a people’s cultural practice over years and centuries. Brimming with pride, self-respect and a farreaching spirit, it is unconstrained by time and space; its techniques may be applied traditionally, but also embody the contemporary spirit of the times. If artists of the East are able to wield ink in their creation, that would be leading the way for our times. (Part 2)

● Source: Part 1 first published in Nanyang Siang Pau, 2 February 1979, p. 18; Part 2 first published in Nanyang Siang Pau, 7 February 1979, p. 27. © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

陈有勇文选摘录 EXCERPTS FROM TAN JOO JONG’S WRITINGS

2. 现代的绘画

毕卡索的作品,虽然一般人难以了解。正如一九O五年,马 蒂斯、德郎、勃拉曼克等人的作品一样,当时的观众都极力 加以否认及讥讽。然而,时至今日,这些人都被公认为代表 那个时代的历史巨匠,若以「英雄」来称呼,也是不为过 的。

要了解现代绘画,必须先追索其根基、历史背景及思想发 展。能够代表各个时代的艺术作品,在现今的观点来看,皆 显现出惊人的活力和极大胆的尝试。

…

目前,现代艺术已步上轨道,然而其所面对的问题是什么? 这不是三言两语所能回答的,也不能以我们所处的时间与空 间来回答。但在各个时代都出现三类艺术家——各个时代艺 术开拓的大师们:第二类的艺术家是继续大师们的基业,加 以发扬光大;第三类是学院派的追随者。第二类艺术家无法 冲破大师们所塑造的范畴时,故临仿其风格,或作技术上的 追崇,只能成为一个技术匠或某一派别风格的捍卫者。

一切的艺术作品,必须赋予作者的个性,通过自己的内心感 受而表现出来,才是真正属于自己的艺术品。一味追随某一 画派或主义,或是有了固定的理论或法则,这种艺术是可悲 的。而一切的派别和主义的评定,都是由评论家、史学家根 据各画家作品之共同处和倾向加以分别而名之。当时之印象 或野兽派画家,都是对前期艺术的一种自然的反抗天性所使 然,产生共通倾向之结果。

然总的来说,绘画应该由繁入简、由形入神、由理入趣,且 要表现出画家之哲学思想;最重要的还是无论在技术、内 容、形式上必需具有创造性。

●(1976年5月刊于《新加坡美术》第3期,7-9页)

2. Modern Art

Pablo Picasso’s works are not easily understood — just as those of Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck in 1905 were vehemently rebuffed and ridiculed. Today, however, these artists are all recognised as masters of that era. It would not be an exaggeration to call them ‘heroes’.

To understand modern art, we must first trace its roots, historical background and ideological development. Works of art that are representative of their respective eras continue to astonish with their vitality and the boldness of their attempts, even when viewed through our eyes today

Currently, the course is set for modern art; yet what are the challenges it faces? This cannot be answered in a few words, nor can it be addressed by the context of our time and space. However, there are three types of artists in every era. They are, firstly, the pioneering masters who pave the way for art in each era; secondly, the artists who build upon the foundation of the masters and expand on it; and thirdly, the academic followers. The second type of artists is unable to surpass the achievements of the masters and can only emulate the latter’s styles or replicate in esteem their techniques, becoming technical practitioners or mere defenders of particular styles.

All works of art must be imbued with the artists’ personality, expressed through their inner feelings, to be truly their own. It would be lamentable if art was to blindly pursue the ideals of a certain school of painting or set of ideology, or to rigidly adhere to a theory or formula. The naming and evaluation of all styles and principles are done by critics and historians according to the similarities and tendencies found in various artists’ works. The Impressionist or Fauvist of their time are identified as those who were motivated by a common propensity for a natural rebellion against preceding art movements.

Generally speaking, art should progress from the complex to the simple, from form to liveliness, and from reason to fascination. Art must express the artist’s philosophy and ideas. Most importantly, art must be creative in technique, content and form.

● Source: First published in Singapore Art, vol. 3, Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau, May 1976, pp. 7–9.

SELECTED WORKS

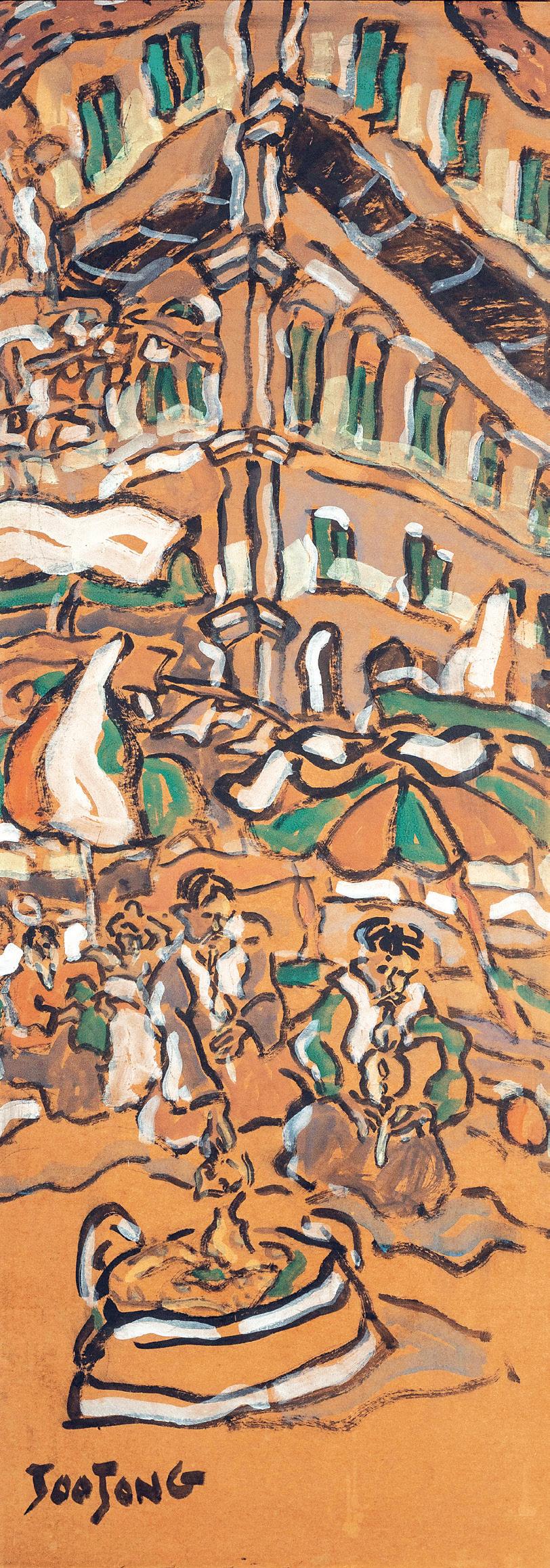

Untitled (Snake Charmer in Chinatown), circa 1975, Oil on board, 160.8 x 57.3 cm

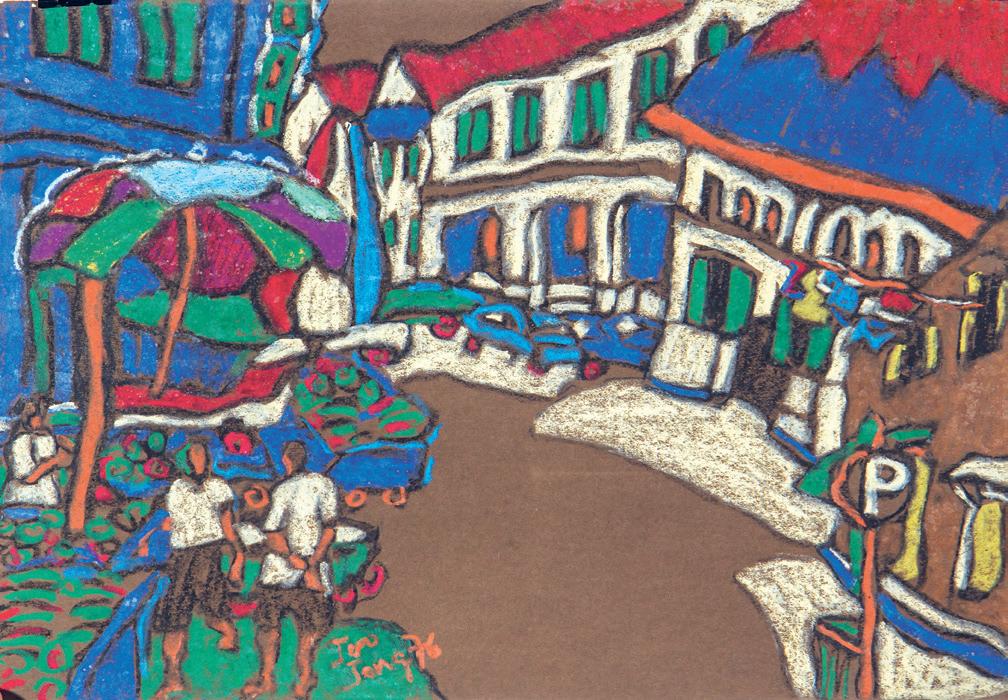

Chinatown, circa 1974, Pastel on paper, 39 x 57 cm

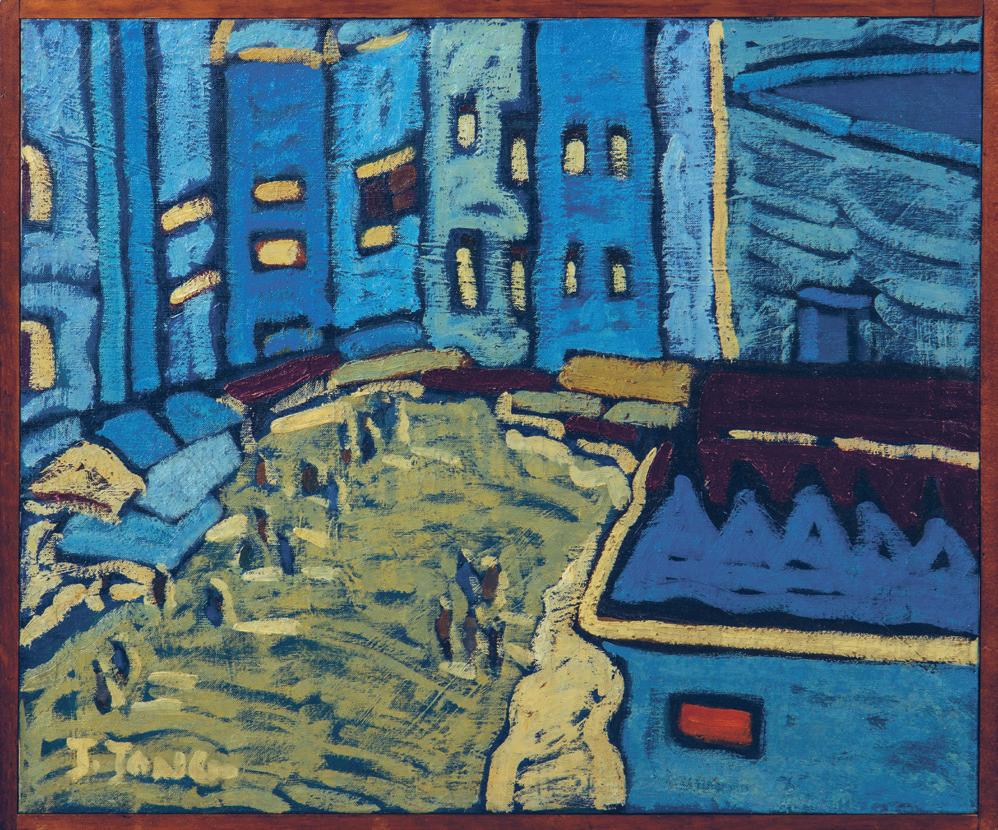

Untitled (From the Rooftop of the Chinese YMCA, Palmer Road), Oct 1974, Oil on canvas, 56.5 x 65.5cm

SELECTED WORKS

Chinese Ink, 1977-1983

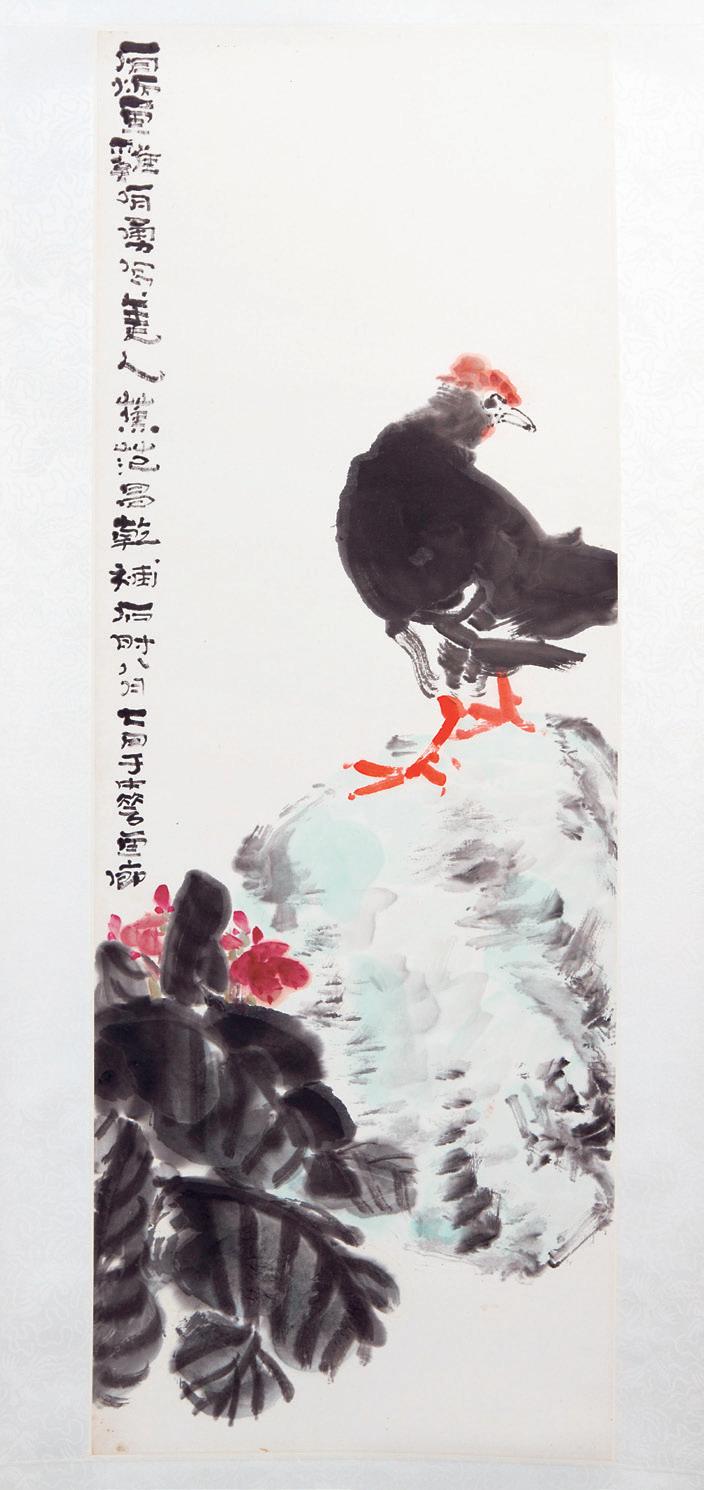

Rooster, Rock and Banana Leaf, (collaboration with Tan Oei Pang and Fan Chang Tien), year unknown (painted at the Chung Hwa Art Gallery on the 7th day of the 8th month), 100 x 36 cm

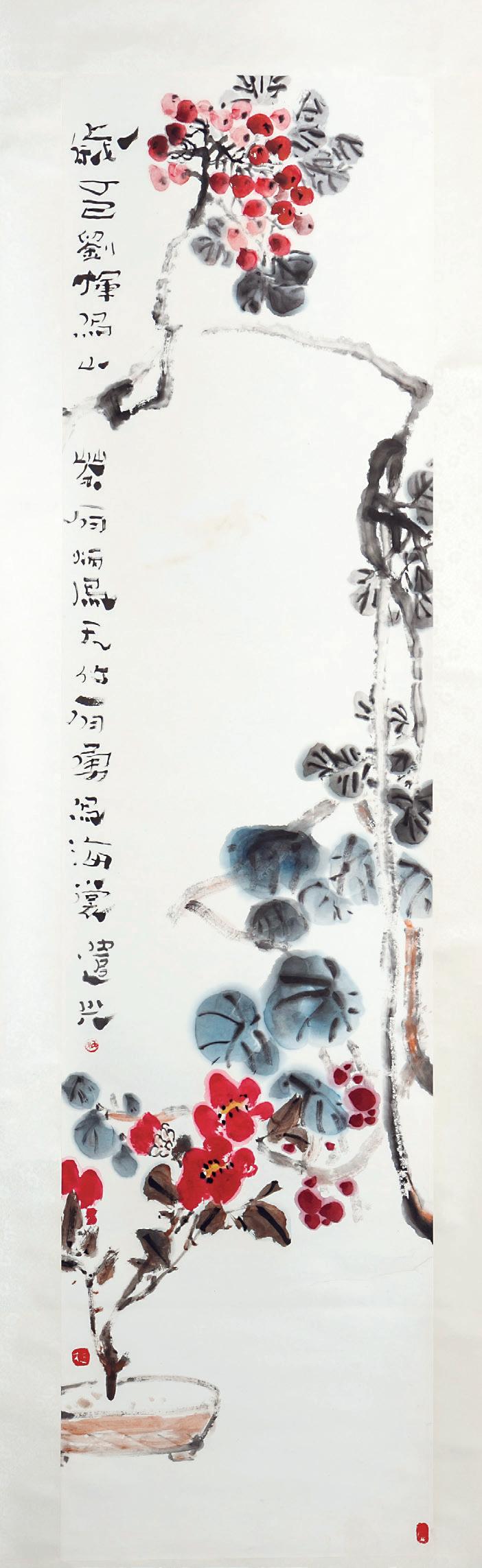

Camellias, Nandina and Begonias, 1977, 丁巳年, (collaboration with Low Eng and Tan Oei Pang), 1977, Ink and colour on paper, 138 x 34 cm

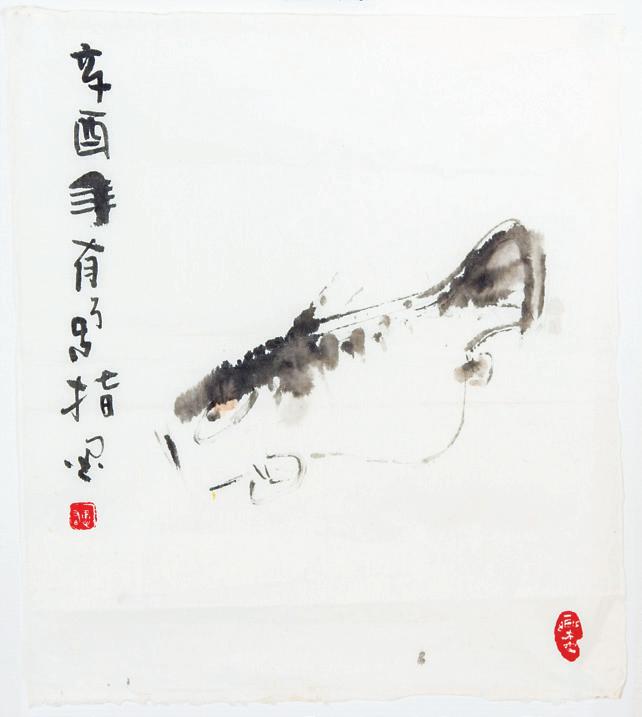

Fish

, 1981, Ink on paper (fingerpainting), 58 x 52 cm

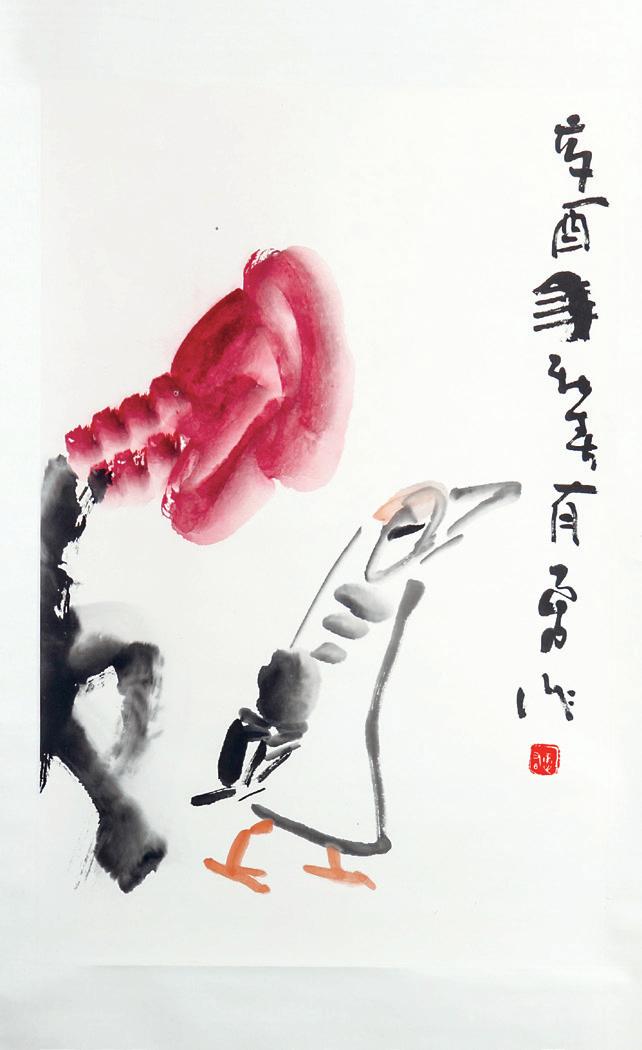

Bird and Flower, 1981, Ink on paper, 67 x 44 cm

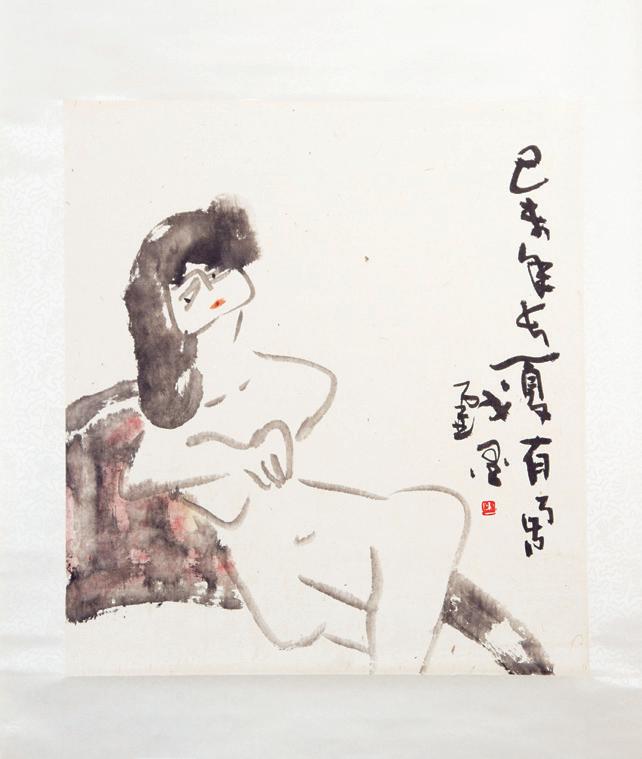

Nude (Portrait of a Lady), 1979, Ink on paper, 59 x 53.5 cm

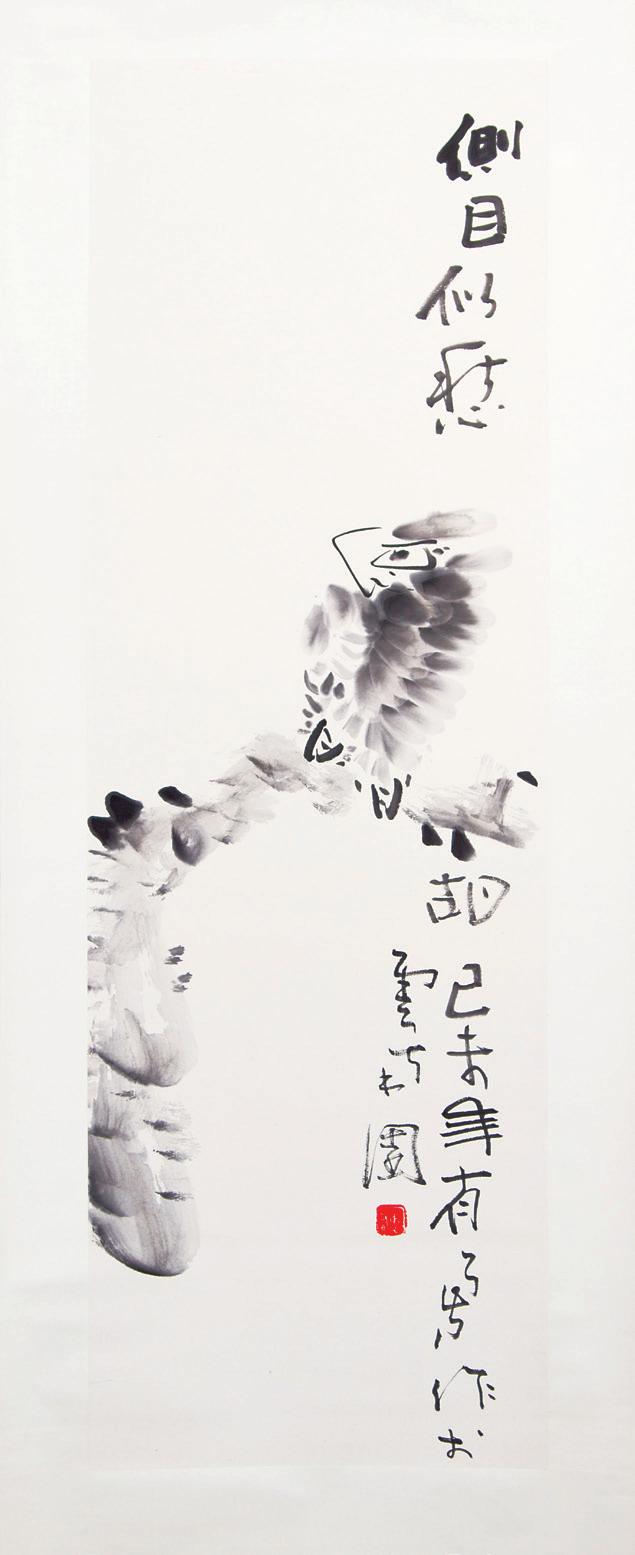

Eagle on Branch, 1979, Ink on paper, 112 x 36 cm

SELECTED WORKS

Chinese Ink, 1977-1983

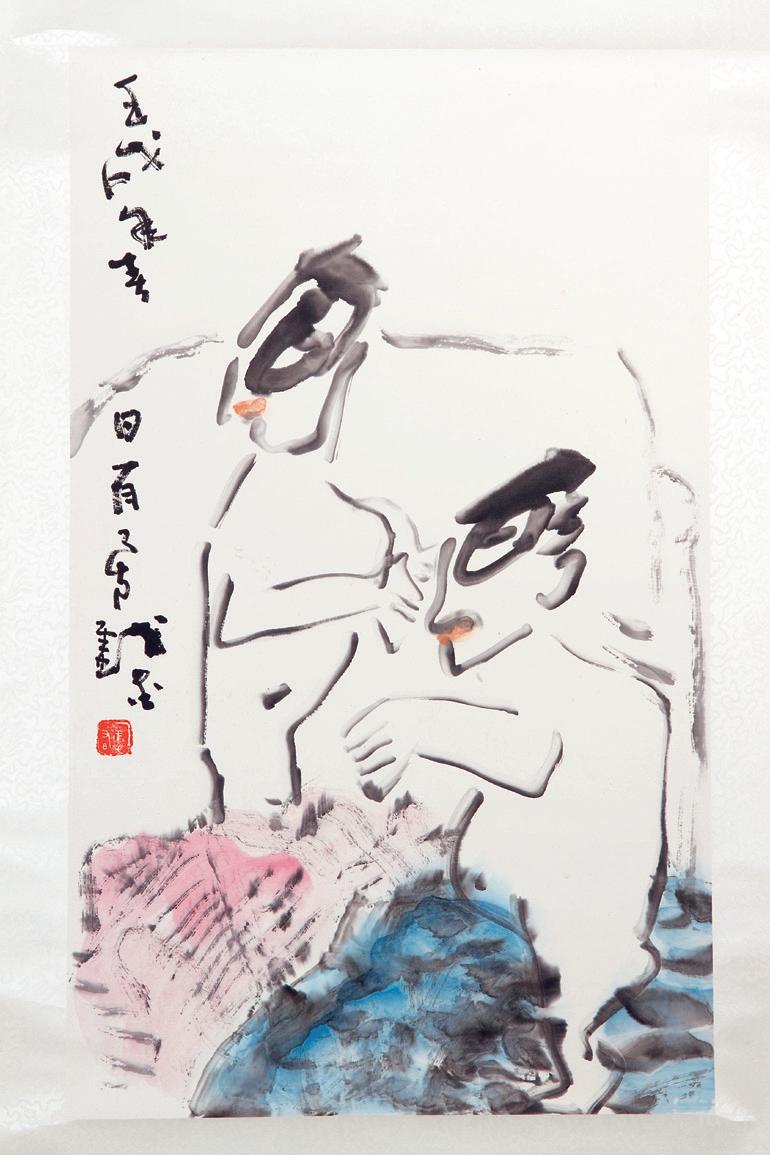

Untitled (Balinese Women), undated, Ink and colour on paper, 138.5 x 34 cm

Untitled (Balinese Men), 1982, Ink on paper, 73 x 44 cm

Acknowledgements

NUS Museum would like to thank the following for their generous support and kind assistance:

Mr Tan Guee Pang

Mrs Tan Joo Jong

NUS Museum is a comprehensive museum for teaching and research. It focuses on Asian regional art and culture, and seeks aexhibitions. The Museum has over 10,000 artefacts and artworks divided across four collections. The Lee Kong Chian Collection consists of a wide representation of Chinese materials from ancient to contemporary art; the South and Southeast Asian Collection holds a range of works from Indian classical sculptures to modern pieces; and the Ng Eng Teng Collection is a donation from the late Singapore sculptor and Cultural Medallion recipient of over 1,000 artworks. A fourth collection, the Straits Chinese Collection, is located at NUS Baba House at 157 Neil Road.

50 Kent Ridge Crescent

National University of Singapore Singapore 119279

TELEPHONE (+65) 6516 8817

EMAIL museum@nus.edu.sg

WEBSITE museum.nus.edu.sg

FACEBOOK facebook.com/nusmuseum

INSTAGRAM instagram.com/nusmuseum instagram.com/nusbabahouse

TELEGRAM telegram.com/nusmuseumbabahouse

OPENING HOURS:

Monday: By appointment (for schools/faculties)

Tuesday to Saturday: 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

Sunday and Public Holidays: Closed

EXHIBITION MANAGEMENT Devika d/o Murugaya

EDITOR Fiona Lim

TRANSLATIONS Yuen Kum Cheong, Chang Yueh Siang

DESIGN Lim Ming Yang

ISBN: 978-981-94-0619-7

© 2024 NUS Museum, National University of Singapore

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher.