DEI GUIDE FOR WALES' ENVIRONMENTAL SECTOR

RACE

FOCUSED REPORT

INTRODUCTION

This research guide serves as a resource for environmental organisations seeking to enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion, addressing the lack of research on underrepresentation in the Welsh environmental sector. It examines the barriers faced by disadvantaged communities in accessing nature-based work and education.

This report shares key findings and practical ideas to help address the challenges faced by ethnic minority communities in rural and coastal North West Wales. It is based on open conversations and honest feedback from people living in these areas, and aims to support real, positive change. The consultation focused on three main goals...

Understanding where we are now – looking at background data and statistics to get a clear picture of the current situation.

Listening to local voices – hearing directly from individuals and groups from ethnic and racial minority backgrounds about their experiences.

Translating learning into action – Reflecting on what has been shared and turning insights into meaningful, actionable steps that environmental NGOs (eNGOs) can use to begin the journey towards genuine inclusivity.

During this consultation process, 123 individuals took part, with a further 78 people directly engaged through detailed focus group discussions, one-to-one conversations, and workshops. The consultation took place against the backdrop of farright riots occurring across the UK, adding urgency and weight to the voices and experiences shared.

UNDERSTANDING DEI IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL SECTOR

UK-WIDE CONTEXT

Additionally, geosciences (the study of Earth such as geology, geography and environmental sciences) rank as the least ethnically diverse discipline at the UK undergraduate level (2017 Policy Exchange report).

T he environmental sector is the second least diverse field in the UK (after agriculture) with only 4.8% of environmental professionals identifying as people of colour, compared to a 15% UK average across all sectors.

Survey results from members of the Ecological Society of America found that historically excluded groups of people including scientists of colour, LGBTQIA+ individuals, disabled individuals and women, were 1.5 times more probable to encounter negative workplace experiences and were more likely to consider leaving their workplace compared to their counterparts. Some issues highlighted were hostility, intimidation or bullylike behaviours, work devaluation and disparaging language (Primack et al 2023).

Additionally, there is often a lack of diverse representation in leadership and senior positions within scientific disciplines. Unsupportive and exclusionary work environments reduce equitable access to resources, opportunities, transportation, communication, and field staff (Nelson et al 2017).

Previous studies have identified several barriers to accessing green spaces for ethnic minorities, including:

FEAR OF RACISM AND SAFETY ISSUES LACK OF CONFIDENCE NEGATIVE PAST EXPERIENCES FINANCIAL CONCERNS

A CLOSER LOOK AT WALES

There is limited official data on the number of people employed in the environmental sector in Wales, making it difficult to accurately assess the diversity and inclusivity of the workforce. Sector-specific statistics for Wales are scarce, which presents a challenge in understanding both the overall representation and the barriers faced by underrepresented groups. This lack of comprehensive, disaggregated data restricts our ability to gain a full picture of how diverse the environmental sector workforce truly is, and the specific challenges that individuals from marginalised communities may encounter.

To address this gap, this report has used qualitative research methods — including focus groups, one-to-one interviews, and anonymous surveys — to amplify the voices of people from underrepresented communities. These approaches provide deeper, more nuanced insights into personal experiences and the lived realities of individuals who are often absent from official statistics. The feedback gathered through these methods reveals both systemic barriers and individual stories, helping to ensure that the perspectives of historically excluded groups are heard and represented.

DIVERSITY IN WALES: A SUMMARY OF 2021 CENSUS DATA

According to the 2021 Census, Wales has a population of approximately 3 1 million people The ethnic composition is predominantly White, with diversity concentrated in urban areas:

White 93 8%

Asian, Asian British, or Asian Welsh: 2 9% (89,000 people)

Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: 1�6% (49,000 people)

Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean, or African: 0 9% (28,000 people)

Other Ethnic Groups 0 9% (28,000 people)

By focusing on the voices of those who could be directly affected, this report aims to provide a clearer, more accurate picture of the state of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the environmental sector in Wales. This qualitative approach ensures that the specific barriers faced by marginalised communities are brought to light, guiding more targeted and effective actions for positive change.

DIVERSITY IN WALES:

A SUMMARY OF 2021 CENSUS

DATA

Although there is little sector specific data on the diversity of the environmental workforce in Wales, census data provides valuable context by illustrating the broader demographic makeup of the population. While it does not allow for direct comparisons with the environmental sector, it can help identify potential disparities in representation and indicate where targeted interventions may be most effective

ETHNIC DIVERSITY IN URBAN AND RURAL WALES: A SNAPSHOT

The map shows that Wales’ ethnic diversity is unevenly distributed, with urban areas generally more diverse than rural regions. This snapshot compares two cities—Cardiff, the most diverse city in Wales, and Bangor, a smaller university city— with two rural towns—Llangefni, one of the least diverse, and Haverfordwest, which reflects broader rural trends.

Percentage of usual residents in wales identifying with an ethnic minority group by local authority (2021 Census)

Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire

(Population: ~14,000)

Haverfordwest, the county town of Pembrokeshire, reflects the broader demographic trends of rural Wales� Pembrokeshire as a whole has a population of around 125,000, with 97.6% identifying as White While ethnic diversity has increased slightly over the past decade, it remains one of the least diverse regions in Wales

The largest minority ethnic group is people of Mixed or Multiple ethnic backgrounds, making up just 0.9% of the population

Llangefni, Anglesey (Population: ~5,000)

Llangefni, a market town on the Isle of Anglesey, reflects the demographics of rural North Wales The town and surrounding areas are among the least diverse in Wales, with 98.1% of residents identifying as White Llangefni has a strong Welsh-speaking community, and migration from outside the UK has historically been low compared to urban centres

Bangor, Gwynedd (Population: ~18,000)

Bangor, a small city in Gwynedd, is one of the most diverse urban areas in North Wales Around 85% of its population identifies as White British, while 15% belongs to non-white ethnic groups. Its diversity is influenced by Bangor University, which attracts students and staff from a range of backgrounds� Cardiff

(Population: ~362,000)

Cardiff, the capital of Wales, is the most ethnically diverse city in the country Around 19�2% of its population identifies as non-white, with significant communities of Asian, Black, and mixed ethnic backgrounds 11

BARRIERS TO ACCESSING GREEN SPACES

“ 83% of White children had access to a garden or green space. Only 57% of Black chidren had similar access. ”

A

ccess to green spaces is essential for the health, well-being, and overall quality of life of individuals and communities. However, numerous barriers prevent full engagement with nature, particularly for underrepresented and marginalized groups. These barriers can range from physical and geographical challenges to socio-economic, cultural, and institutional factors. Understanding these barriers is key to fostering inclusivity and ensuring equitable access to outdoor spaces for all.

- Youth Statistics (The Wildlife Trusts, 2022)

“Access

to highquality green space

is

a fundamental determinant of wellbeing , providing both physical and mental health benefits, especially for those in disadvantaged communities.”

- Natural Resources Wales (2021)

“11

million people in the UK live in areas with limited access to green space”

- Friends of the Earth (2021)

WHAT’S HOLDING ENVIRONMENTAL NGO’S BACK?

We spoke with a range of chief executives and operational managers from small and medium-sized environmental NGOs (eNGOs) working across rural and coastal Wales.

When asked about the challenges they face in improving racial and ethnic inclusivity, respondents painted a picture of a sector already under significant pressure — dealing with staff shortages, limited funding, and a lack of time to explore the deeper, systemic issues. Many raised concerns about the long-term sustainability of their work, while also describing the resistance they encounter when engaging with wider systems, decision-makers, and institutions.

Key Challenges Faced by eNGOs in Advancing Racial and Ethnic Inclusivity:

Geographic Isolation and Transport Barriers

Language and Communication Gaps

Information is often presented in technical or academic language, or only in English/Welsh, which can alienate people who speak other first languages or who are unfamiliar with the sector’s jargon.

Lack of Representation in Local Populations

Rural and coastal areas of Wales often have lower ethnic diversity, making it harder for organisations to identify and build relationships with local minority communities.

Limited cultural awareness and training

Many staff and volunteers have not received training in cultural competency or antiracism, leading to uncertainty about how to engage inclusively and respectfully.

Historical Exclusion and Mistrust

Some communities may have had negative past experiences with institutions, or feel excluded from traditional narratives of “nature” and “conservation,” which can create mistrust or disconnection.

In remote rural areas, public transport is limited or non-existent, making physical access to events, jobs, or volunteering opportunities difficult for many — especially those without a car or facing economic hardship.

Fear of Getting It Wrong

Some staff feel nervous about saying the wrong thing or unintentionally causing offence, which can lead to inaction or tokenistic approaches.

Funding Structures That Don’t Support Long-Term Inclusion Work

Short-term, project-based funding often doesn’t allow the time or flexibility needed to build trust with communities or support longterm inclusive practices.

Staff Capacity and Resource Constraints

Small teams with limited funding and overstretched workloads often struggle to prioritise or properly resource inclusive engagement work.

Structural Barriers Within Institutions

The absence of

ethnic minority leaders or staff within the environmental sector in Wales makes it harder for young people to see a place for themselves.

Decision-making processes within eNGOs, funders, and partner organisations can be slow, hierarchical, or exclusive, limiting meaningful participation from underrepresented communities.

INDUSTRY ASSUMPTIONS

What we heard – and why it’s time to look again

I

n our NGO management consultation we discovered that many rural environmental groups assume there’s no ethnic diversity in their areas, but local data and lived experiences as outlined earlier in this report show otherwise - diverse communities are present, just often overlooked by typical outreach and engagement methods.

“There are no ethnically diverse people in our catchment, so DEI isn’t relevant to us.”

“There’s no-one here”

If you aren’t seeing diversity in your work, it’s likely not because it isn’t there—but because your outreach, access routes, or environments aren’t resonating. Inclusion takes intent—not assumption.

Know your patch –properly.

Use local authority data (e.g. Gwynedd, Conwy, Powys) to understand ethnic and linguistic diversity. Contact your local council’s equality officer, schools, or community health teams for anonymised insights.

Build trust before asking for involvement.

Show up without asking for input or partnership immediately. Attend community events as a guest, listen, and earn permission to co-create.

Go where people are.

Advertising solely through your own newsletter or Facebook page is not enough. Translate materials where needed, visit communities in person, use WhatsApp and religious or cultural centres.

FROM RACIAL EQUITY TO RACIAL JUSTICE

Why It Matters for eNGOs in Wales

L

ori Villarosa and Rinku Sen from the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE) highlight the importance of moving from a racial equity lens to a racial justice lens when working towards meaningful change. This distinction is important for environmental NGOs seeking to deepen their commitment to inclusion.

For eNGOs in rural and coastal Wales — this means asking not just “How do we include more diverse voices?” but also:

A racial equity lens helps identify disparities and separate symptoms from causes. It focuses on fair access, treatment, and opportunity for all people, and is often a good starting point.

A racial justice lens, however, goes further. It looks at how power operates, calls for the redistribution of resources, and aims to transform the systems and structures that create inequality in the first place.

“How are we sharing power with the communities we want to serve?”

A RACIAL EQUITY LENS A RACIAL JUSTICE LENS

• Analyzes data and information about race and ethnicity.

• Understands disparities and the reasons they exist.

• Look at structural root causes of problems.

• Names race explicitly, when talking about problems and solutions.

“Who holds power and makes decisions in our organisation?”

“Are our partnerships and fundingreinforcingstructures exclusion?”

Adopting a racial justice lens means shifting from treating inclusivity as an add-on or a tick-box exercise to embedding it in the core mission, governance, and operations of the organisation.

• ...adds four more critical elements:

• Understands and acknowledges racial history.

• Creates a shared affirmative vision of a fair and inclusive society.

• Focuses explicitly on building civic, cultural economic, and political power by those most impacted.

• Emphasizes transformative solutions that impact multiple systems.

While this work is complex and long-term, it is essential if we are to build an environmental movement in Wales that is fair, resilient, and representative of all communities.

LIVED EXPERIENCE & INSIGHTS

EXPLORING BARRIERS TO A MORE DIVERSE & EQUITABLE ENVIRONMENTAL SECTOR

SURVEY

What is the best way to be contacted by organisations?

An online survey was made available to the public for several weeks, widely advertised through posters and social media to ensure accessibility.

The survey aimed to collect confidential feedback on barriers to the environmental sector. Demographic data was also gathered to provide context for the responses.

The anonymous format was designed to create a safer space for participants to discuss sensitive topics and identify the resources and opportunities they need.

Although the online survey provided a useful starting point, its limitations became apparent during analysis. To explore the issues more meaningfully and hear people’s lived experiences in greater depth, we followed up with targeted in-person interviews.

... of respondents identified as ethnically diverse

What type of support/ resources would make it easier to access environmental spaces?

... of respondents believed racial/ ethnic discrimination to have been a barrier in education or career development

59.2%

... of respondents believed where they grew up limited their opportunities to take part in nature

Most popular answers Most popular answers

Free travel to volunteer days or stakeholder events

What barriers do you face in accessing green spaces or careers in the environmental field?

More awareness of events through a greater range and frequency of advertising

Funding for exhibitions, kit / internships / opportunities to gain experience

How could the environmental sector be more inclusive? Most popular answers

• Secure long-term, reliable funding to support inclusive work.

• Provide regular, tailored training so staff have the knowledge and confidence to embed racial equity into their everyday practice.

• Target community involvement and outreach.

• Create paid entry-level roles for students.

• Provide targeted free activities for adults as well as children.

• Improve promotion of activities.

• Offer flexible, family-friendly volunteering.

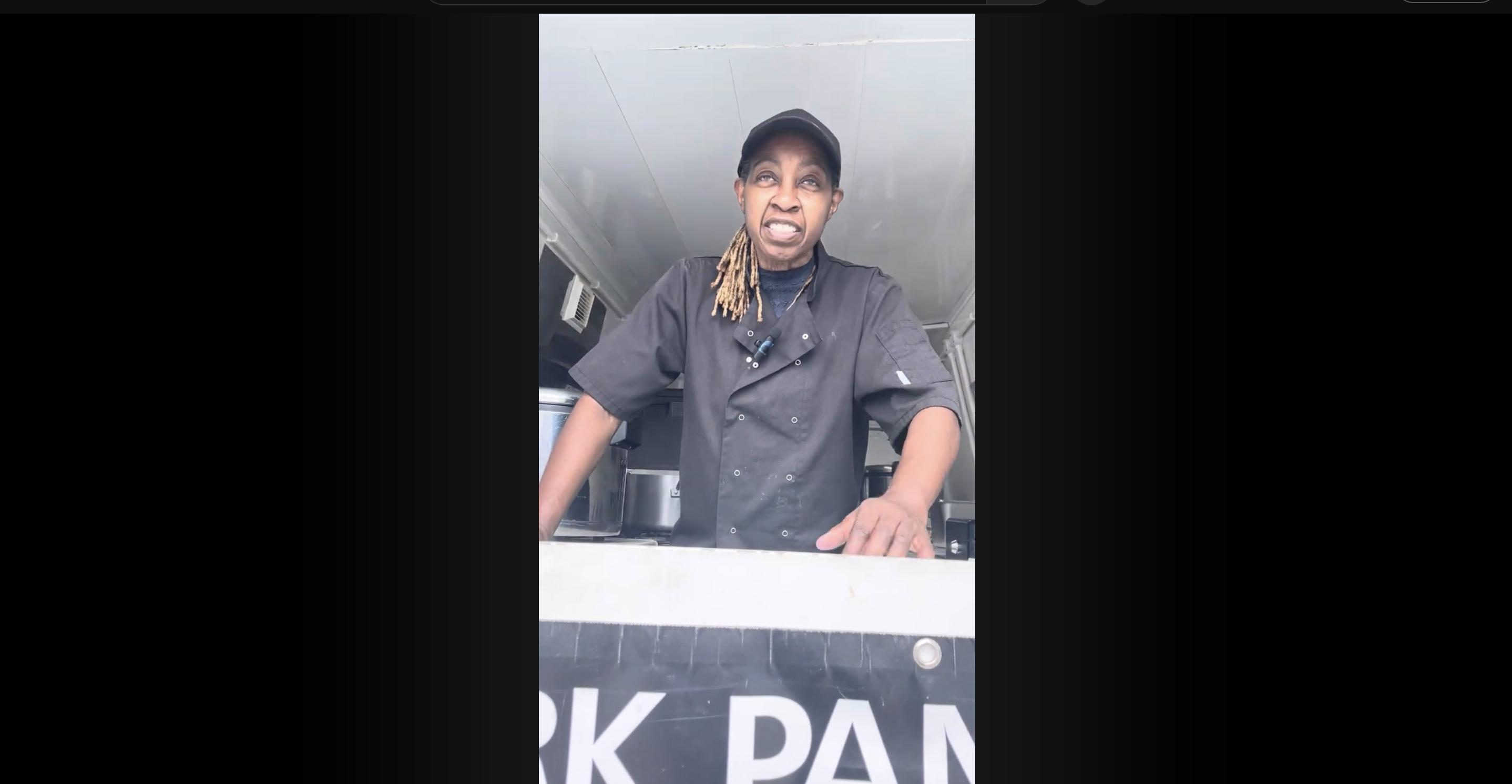

SNAPSHOT INTERVIEWS

To better understand the barriers to inclusion and access, we visited the local street market in Bangor, North Wales, to engage directly with people from a variety of backgrounds. We conducted in-person interviews with individuals from diverse cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic contexts, spanning both rural and urban areas across North Wales.

These conversations revealed valuable insights into the factors that may contribute to underrepresentation or disengagement from nature-based and environmental career pathways.

What emerged was clear: many people hold distinct perceptions of the environmental sector and face both practical and systemic barriers to engaging with it. These challenges must be recognised and addressed if we are to create truly inclusive access to environmental opportunities.

1 What environmental or nature-related jobs do you know about? Have you ever considered working in this field?

2

Would you be interested in joining an environmental training or activity? Why or why not?

WE FOCUSED ON THREE GUIDING QUESTIONS TO HELP SHAPE OUR APPROACH:

3 What can we do to make the environmental sector more welcoming and inclusive for people from diverse backgrounds?

Perceptions of the Environmental Sector

John associates the environmental sector with farming and has considered working in nature due to his love of peace and quiet� Living at the intersection of built-up, coastal, and countryside areas, he feels drawn to spending more time in natural spaces

Interest in Training and Engagement

John expressed interest in participating in an environmental training program, particularly in understanding the logistics of how the sector operates� However, time constraints pose a significant barrier for him, as his business commitments are demanding Any activities would need to be scheduled at convenient times to fit into his busy schedule

Suggestions for Inclusion

To make the environmental sector more inclusive and engaging, John suggested fostering business collaborations between organisations and local partners For example, linking environmental work with farmers’ markets or partnering with farmers could create networks that encourage broader community participation

Name: John

Location: Rhyl

Heritage: Sumang Oriental Filipino

Name: Sarfaraz

Location: Bangor

Heritage: Indian

Perceptions of the Environmental Sector

Sarfaraz, a tech shop manager with Indian heritage based in Bangor, has not previously engaged with the environmental sector However, he enjoys gardening and planting trees, which aligns with his interest in nature

Interest in Training and Engagement

Sarfaraz is keen to participate in environmental training activities during his free time With a master’s degree in management, he is particularly interested in learning about land and woodland management The main barrier for him is balancing his free time, as he enjoys traveling and exploring He would be more inclined to participate in activities that offer opportunities to visit new locations, ideally with transport provided

Suggestions for Outreach

Sarfaraz emphasized the importance of environmental education and outreach within underrepresented communities He suggested leveraging social media to connect people across rural Wales and using leaflets to distribute information about campaigns and events to residential areas Direct communication with rural communities about upcoming events would also encourage participation

Name: Pauline

Location: Harlech

Heritage: Jamaican / British

Perceptions of the Environmental Sector

Pauline immediately associated the environmental sector with farming and said it doesn’t appeal to her She sees a stark contrast between how nature is valued in the UK and the West Indies—where it’s central to daily life and survival In the UK, she feels a “broken system” fosters disconnection from nature

Interest in Environmental Activities

Pauline enjoys growing her own seeds and producing organic food but is often held back by a lack of free time

Challenges and Opportunities

She sees a need for Afro-Caribbean communities in North Wales to connect and support one another Pauline believes environmental organisations could help create these spaces She also noted economic pressures, with many parents favouring financially stable careers over environmental work, which limits long-term involvement in the sector

Scan the QR code to hear Sarfaraz talk about her experiences

Name: Cella

Location: Holyhead, Ynys Mon

Heritage: Nigerian / British

Perceptions of the Environmental Sector

When Cella thinks of careers in the environmental sector, organisations like the RSPCA, working with birds, and park warden roles come to mind However, she had not heard of smaller local organisations such as the North Wales Rivers Trust Cella expressed an interest in working with animals in sanctuaries and said she would consider a career in the sector

Interest in Training and Engagement

Cella is open to participating in environmental training programs and trying new experiences However, she made it clear that she has no interest in paperwork, preferring hands-on engagement instead

Challenges and Calls for Action

Cella strongly believes that environmental organisations need to advocate for vulnerable communities that have been ignored or silenced She highlighted the example of Anglesey’s Penrhos Coastal Park in Holyhead, where land that was initially meant to be gifted to the community for reforestation following aluminium pollution was instead sold to a property developer for a leisure village She criticized the council for prioritizing business and financial investments over the interests of young people and the community In her view, environmental organisations should step up to address environmental injustices like this, build relationships with communities, and become allies rather than bystanders 1

“Environmental education needs to reach underrepresented communities — especially through social media and trusted local leaders.”

“There’s a need for Afro-Caribbean connections in North Wales — to support one another and be visible in these spaces.”

(On representation and support networks)

(On outreach strategy)

“I’d consider a career in the sector — I just hadn’t heard of local organisations like North Wales Rivers Trust before.”

“I’d

be more likely to get involved if it took me to new places — and if there was help with transport.”

(On practical access and engagement)

“There’s a broken system in the UK. In the West, nature is disconnected from daily life and survival.”

(On how environmental values differ across cultures)

“That land was meant to go to the community — but it was sold to a property developer. No one consulted us.”

“Environmental organisations should stop being bystanders and start addressing injustice. They need to become allies.”

( On accountability and action) (On visibility and awareness)

(On environmental injustice and lack of community voice)

FOCUS GROUPS

TTo build on our initial findings, we hosted a series of in-depth focus groups, both virtually and in person. Each session brought together small groups (three or more participants) to spark open, honest conversations and explore the challenges in greater depth.

We made accessibility a priority by offering a range of participation formats, mindful of people’s time, travel needs, and access to technology. This flexible approach allowed us to hear from a wider variety of voices — not only from local Welsh communities, but also from participants based in other parts of the UK, adding richness and national context to our understanding.

Two virtual focus groups connected individuals from both rural and urban areas. We asked five key questions focused on access to green spaces, barriers to environmental work, and what inclusive environmental futures could look like. What emerged were honest reflections, shared frustrations, and a strong desire for change — including calls for greater visibility, trustbuilding, paid opportunities, and better cultural representation in the sector.

1 What careers do you know of in the environmental sector? Have you ever explored a career in the environmental sector? Our 5 key questions:

2

Did you grow up in an urban or rural area? Did this affect your participation in nature-based volunteering/work/education?

3 What reasons may there be for the lack of diversity in the environmental sector?

4 How can we engage marginalised groups in the environmental sector and remove barriers limiting their interaction in environmental spaces?

5 What forms of contact are most accessible for you or your community? (social media/ radio/ email/ posters/ word of mouth/ community billboards/ other?)

1

1

What careers do you know of in the environment sector?

Have you ever explored a career in the environment sector?

“I had to actively seek out nature. It wasn’t around me.” – Jacob

2

Challenges faced by individuals raised in urban environments

Rural programmes should offer maps, video guides, and newcomer-friendly support access.

“It’s rewarding, physical, and clears your head”

“It’s seen as something you do for free - not a real job.” – Ashley

Lack of services like guides, signage, and beginner resources limited access.

3 What reasons may there be for the lack of diversity in the environmental sector?

Safety concerns: Joe felt unsafe as a gay person of colour in rural green spaces

— highlighting how racism and homophobia can compound exclusion.

Cost & transport were major barriers, especially in rural areas.

Not feeling included

Inner-city, disabled, and minority communities often feel disconnected from nature.

Environmental work is often seen as low-paid or only for the middle-class or privileged.

Lack of access to nature

Limited access to green spaces lowers interest in nature-based careers.

Transport costs and lack of local programmes create further barriers.

Feels distant from real-life priorities

Environmental issues are often seen as unrelated to immediate concerns like housing, income, or health.

The sector rarely presents messages or opportunities in culturally relevant or practical ways.

Physical & Structural Barriers

Many outdoor sites are not disability accessible.

Marginalised groups often lack community-based environmental opportunities.

Lack of representation and career pathways

Concern for personal safety

Racism, homophobia, and social exclusion deter people from marginalised groups in rural or outdoor spaces.

Many feel unsafe or unwelcome in traditional environmental settings.

Few visible role models from diverse backgrounds in the sector.

Limited job training or career pathways for underrepresented groups.

How can we engage marginalised groups in the environmental sector?

Make outdoor access inclusive: Enable people with disabilities to join hikes, volunteering, and nature-based activities.

Go beyond PR: Embed real DEI practice through transparent hiring, training, and representation.

Go to where people are: Partner with grassroots groups and host inclusive, cocreated events.

Integrate with everyday life: Connect environmentalism to housing, arts, food, and cultural identity.

Create safe, accessible spaces: Use digital tools and real-world venues designed for comfort and belonging.

Design with care: Host events specifically for marginalised groups, with childcare, incentives, and community benefits.

Link nature wellbeing:toFrameactivitiesenvironmental around mental health, creativity, food, or fun.

Educate and inspire: Show that environmental work can be enjoyablemeaningful, — economicallyand sustainable.

5 What forms of communication are most accessible for you or your community?

Social media: Widely used, especially by younger audiences. Word of mouth: trusted and effective in close-knit or rural communities.

Schools and education centres: important hubs for reaching families and young people.

Posters and community noticeboards: in high-footfall areas like shops, bus stops, and libraries.

This summary condenses key points from conversations. To hear the full perspectives and personal experiences shared in the focus group, watch the video.

Local radio: Particularly accessible for older generations.

UNDERSTANDING LIVED EXPERIENCES

In-depth interviews:

To deepen our understanding of the challenges faced by individuals within and outside the environmental sector, we conducted a series of in-depth one-to-one interviews.

These interviews explore both the barriers encountered by those already working in the sector and the perceptions and experiences of those unfamiliar with it. Through this process, we identified key themes, discussed potential solutions to address the challenges, and highlighted positive aspects.

Johnathon, 24 Conservationist and wildlife enthusiast, educational content creator Scan the QR code to hear Johnathon talk about his experiences

Nature Connection: Loves walking, cycling, skating outdoors, and observing birds, fish, and insects. Childhood fascination with exotic animals and bones sparked her passion for zoology.

Current Role: Intern at Synchronicity Earth, working on global freshwater/ocean conservation with Indigenous communities.

Passion: Inspired by evolution and adaptation — sees ancient organisms as keys to understanding both nature and human history.

Career Journey:

• Transitioned from retail and finance to conservation through university, traineeships, and social media wildlife content.

• Gained core skills via London Wildlife Trust’s ‘Keeping It Wild’ – from community engagement to comms.

Barriers Identified:

• Qualifications & gatekeeping: Entry-level roles often require degrees and unpaid volunteering, limiting access.

• Low pay: Environmental roles are undervalued financially, despite their importance.

• Isolation: Felt like the only Black male interested in wildlife growing up; few role models in the sector.

Systemic Solutions

• Push for top-down change: Sector leadership must prioritise DEI, not just individuals.

• Focus efforts on disadvantaged areas: Bring nature access, workshops, and fieldwork to overlooked communities.

• Expand traineeships and revise school curriculums to reflect diverse nature stories and careers.

• Celebrate uniqueness: Make diverse identities feel welcomed, not exceptional.

Lershae, 25 Lives in Bangor, North Wales, though she grew up in Manchester Heritage: Jamaican

“Diversity means learning new perspectives that you may have never experienced... it means being able to grow.”

- Lershae

Access Barrier: No car = limited access to nature. Calls for better public transport.

Lived Experience: Faced microaggressions as a neurodivergent Black girl; nature wasn’t visible or accessible growing up.

Interests: Passionate about music, but inspired by botanical gardens to apply to the National Trust. Finds nature grounding and ADHD-friendly.

Urban Inequality: Highlights how urban development reduces green space for minority communities.

Engagement Tips: Wants welladvertised, inclusive, affordable events with activities for all ages.

To attract more diverse communities, organisations need to ensure they have diverse experts and relatable role models.

As Lershae puts it, “It is so beneficial to see yourself in a position you may have never seen before... to know, Okay, I can do it.”

- Lershae

Joe, 20 Environmental Conservation graduate, raised in the rural Peak District

Lives in Bangor

Joe’s main challenge in accessing green spaces and environmental work is transport. Without a car, his employment opportunities are limited. primarily due to financial constraints and the difficult bus system in rural North Wales.

Early Connection: : Developed a love for mountains and nature growing up in the countryside.

Career Views: Sees the sector as consultancy-heavy and hard work-focused, but values the positive impact nature can have on well-being.

Barriers Faced:

• Faced racism at school as the only mixed-race student.

• Felt alienated at university, particularly by lecturers whose values clashed with his (e.g. hunting culture).

Access Challenge: Lack of transport limits job options — rural North Wales has poor public transit and low pay, making car ownership hard.

Inclusion Insight: Wants open, stigma-free dialogue in the sector and more diverse staff and media representation to create safer spaces.

Stephanie, 21 Nature enthusiast and aspiring zoologist, with a passion for cichlids and biodiversity Studying zoology in Bangor, from London Heritage: Guinea-Bissau

Regarding diversity in the environmental sector, Stephanie notes a significant lack of awareness about environmental careers. Environmentalism is often perceived as a ‘white job’.

Nature Connection: Loves walking, cycling, skating outdoors, and observing birds, fish, and insects. Childhood fascination with exotic animals and bones sparked her passion for zoology.

Urban Barriers: Noise, light, and pollution make urban green spaces feel uninviting. City life disconnects her from the land and seasonal changes.

Access in Wales: Lack of a car and poor public transport limits access to rural nature in Wales.

On Diversity & Representation :

• Feels the sector is often seen as a “white job” and not prioritised in some immigrant communities, where medicine or law are considered more viable.

• At university, she was one of only three people of colour in her classes; most staff were white and male.

• Missed representation: She wasn’t taught about POC zoologists or naturalists and sees a real lack of diverse role models in education and media.

Solutions & Engagement Ideas:

• Promote environmental careers through schools with diverse role models across topics.

• Raise awareness of high-level and business-related roles within the sector to challenge career stereotypes.

• Reach marginalised communities by: 1. Advertising events in local parks and public spaces during summer. 2. Going to neighbourhoods directly for feedback and co-creation of programmes. 3. Making decision-making more community-led and inclusive, especially in city centres

Chad, 25 Marine biologist and zoologist

Heritage: Jamaican

For Chad, a welcoming environment is largely determined by the attitude of the staff. A warm reception at work or events is key to feeling comfortable.

Nature Roots: Grew up closely connected to nature in Jamaica — sparked his passion for wildlife and conservation.

Student Experience: Often the only person of colour in lectures, which has affected his comfort and attendance.

Career Interests: Drawn to wildlife media, zoo work, and hands-on conservation.

Barriers: Mental health and anxiety may limit participation in training or programmes.

Engagement Tip: Environmental orgs should actively connect with student groups of colour to improve outreach.

Inclusion Insight: A welcoming space depends on staff attitude. Anti-racism and inclusion training is key.

Jetta, 21 MSc Entomology

student, aspiring museum curator with a passion for insect conservation

Heritage:

Welsh and AngloIndian

Scan

Career Goal: Wants to manage insect collections in museums, focusing on wasps as natural pest controllers in agriculture.

Academic Path: Studied Wildlife Conservation, now completing a master’s in Entomology.

Barriers Faced:

• Financial constraints limited access to placement years and training.

• No car or licence = reduced mobility and fieldwork access in rural areas.

• Suggests better bike routes, carpooling, and networking events to share fieldwork contacts beyond personal networks.

Supportive Opportunities

• Hands-on experience through Bioblitz, Duke of Edinburgh, and student-led societies.

• Encouraging academic staff helped her build confidence and connections. Diversity & Inclusion

• Noted a lack of diversity in the field, which makes it harder to relate to peers.

• Motivated to be a role model for others and increase representation. Recommends:

• DEI training for staff

• Diverse leadership

• Accessible events via public transport, inclusive communication (captions, newsletters, socials)

• Wheelchair-friendly routes and multiple access formats

COMMUNITY CONVERSATIONS

Exploring barriers and opportunities in Wales

T

o gain real insight into the experiences of local communities in Wales, we ran four engagement events. This included one open session on diversity in the environmental sector, and a more focused workshop held at the North Wales Africa Society’s community base.

These different formats helped us test what actually works to build trust and participation. Crucially, they revealed clear barriers—like transport, confidence, and lack of targeted outreach—that are often overlooked or misunderstood by organisations. They also gave us a clearer picture of where people are starting from and what support is really needed.

Trialling different engagement approaches: what worked, what didn’t

To better understand how to engage underrepresented communities in the environmental sector, we trialled four different types of engagement events. Each format was designed to test different levels of openness, setting, and audience familiarity, allowing us to explore what builds trust and where barriers still exist.

1. Listening session

We began by attending a closed-group session with a community group focused on climate issues. This was a listening and relationship-building event held in a trusted community space. It gave us the opportunity to get to know the group, understand key concerns, and introduce our work in a non-pressured environment.

2. Open public river walk event:

Following the session, we invited attendees to a wider river walk open to the general public and advertised across our channels. Several participants signed up during the previous event, showing clear interest. However, closer to the date, they withdrew due to last-minute work and childcare commitments— highlighting that even motivated attendees face real-life barriers to participation when events are not tailored to their needs.

3. River art workshop in a community Space:

We then held a closed-group children’s river workshop directly in the groups community building. This event had a strong turnout and was well received by both children and parents. The familiar setting, targeted format, and accessible timing helped build trust and laid the foundation for future partnership work.

4. Snorkel survey event –a missed opportunity:

We also invited NWAS participants to one of our regular snorkel survey sessions. While there was high interest, we hadn’t accounted for the fact that some participants had never learned to swim and they thought this would be provided. This meant they couldn’t safely take part—a valuable reminder not to assume everyone shares the same baseline skills, especially when offering specialised activities.

Case study 1

Creative workshop with North Wales Africa Society Building relationships and attending an event as participants to get to know the group.

Format: Art-based workshop exploring activism, identity, and local colonial history (e.g. HM Stanley statue)

Activity: Participants designed monuments celebrating people of colour

Location: Held at NWAS community space — safe, familiar, and locally accessible

Turnout: Well-attended by community members, with participants highlighting the value of being in a safe space among people with shared lived experience

Engagement: In-person focus group held during the creative session, using 3 guiding questions

Key Conversations:

• Reflections on safety, identity, and racism

• Discussion of recent hate crimes and rising far-right activity (Aug 2024)

• Participants felt safer in Wales than in larger English cities

• Younger attendees were highly aware of these issues via social media

Case study 2

Guided river walk (Cegin Valley)

Format: Family-friendly, educational walk on river ecology, INNS, and water testing

Promotion: Shared via social media, posters (urban/rural), and direct invites to diverse community contacts

Attendance: All attendees were white; no people of colour attended despite confirmed interest

Barriers Identified for non attendance:

• Schedule conflicts (e.g. shift changes)

• Last-minute dropouts

EVENT 1

• Interest in signing up to our wider river walkover event.

This was an open event to all in the community and we had signs up from our previous workshop. However they were unable to attend.

Insight: Even friendly, open events can miss the mark with ethnically diverse communities if there isn’t some upfront, tailored outreach or time spent building relationships first. This needs to be more than an introduction session.

Case study 3 River art workshop (Ages 4–16) at Bangor African and Caribbean Centre We designed and created a river workshop at the groups community premises. This was well attended.

Format: Creative workshop engaging children with local river issues through art and discussion

Activity: Participants designed a river, wrote wishes for its future, and learned about pollution, sewage, and climate change

Topics Covered:

• Climate change awareness (even among youngest attendees)

• Pollution, sewage flooding, and fish population decline

• Children expressed strong advocacy for cleaner, healthier rivers

Turnout: High attendance, likely due to:

• Saturday timing

• Familiar, safe venue (BACC)

• Age-inclusive, hands-on format with art supplies provided

Accessibility: Parents felt confident leaving children in a trusted community setting

Promotion: Advertised via North Wales Africa Society, directly reaching local families

Insight: Community-based, closed-group events in familiar spaces generated stronger engagement than open-access, travel-dependent ones

Case study 4 Community snorkel event invitation

Activity: Participants were invited to take part in guided snorkel sessions to explore local freshwater habitats, supported by trained staff.

What Happened: While several NWAS participants signed up enthusiastically, many later reached out to ask whether swimming lessons or water confidence training would be provided—highlighting that some attendees couldn’t swim. This revealed a key assumption: we hadn’t considered that not everyone would have basic swimming skills, especially within ethnically diverse or underserved communities.

Barrier Identified:

• Absence of prior swim instruction

• No prior experience in open water

• Missed opportunity due to activity-specific access needs

We extended an invitation to North Wales Africa Society (NWAS) members to join one of our regular snorkel survey workshops, aimed at engaging communities with rivers through inwater exploration and biodiversity recording.

Insight: High interest doesn’t guarantee accessibility. We must stop assuming shared starting points. For many communities, especially those underrepresented in the environmental sector, there are unseen barriers like swimming, driving, or prior exposure to outdoor activities.

Recommendation:

• Offer water confidence and swim training in advance of future snorkel or in-water sessions.

• Partner with local leisure centres or Swim Wales to bridge the skills gap before delivering water-based activities.

Learning Point: Enthusiasm was high, but assumptions about skill level created unintentional exclusion. Future inclusion means meeting people where they arenot where we expect them to be.

Our events highlighted a consistent pattern:

Trust, familiarity, and belonging drive engagement.

Turnout was significantly higher when activities were held in familiar, community-led spaces with people participants already knew and trusted. In contrast, attendance at broader, open-invitation events was lower, with common barriers cited including last-minute work scheduling and transport difficulties.

This suggests that to build genuine inclusion:

1

Environmental organisations must start by working within closed or communityspecific groups, offering welcoming, naturebased activities where people feel safe, seen, and valued.

2

Only once trusting relationships are established should these efforts be gradually extended into broader programmes. Inclusive engagement must be built, not assumed— starting with presence, listening, and sustained partnership.

ACTIONS YOUR ORGANISATION CAN TAKE TODAY

The environmental sector has the power to bring people together, inspire action, and create meaningful change— but only if everyone has a seat at the table. This report highlights key recommendations to break down barriers and build a more inclusive sector where diverse voices shape decisions, opportunities are accessible to all, and nature truly belongs to everyone.

ACTIONS YOUR ORGANISATION

CAN TAKE TODAY

Based on a combination of formal and qualitative research — including online focus groups, anonymous surveys, and in-person discussions—these recommendations address challenges in employment, workplace culture, community engagement, and representation. From fair hiring practices and paid internships to decolonising environmental education and making outdoor spaces more welcoming, this report outlines practical steps towards lasting change.

While these findings provide valuable insights, no single approach can capture the full diversity of experiences across Wales and the UK. Interventions must be tailored to specific communities, and ongoing collaboration is essential to ensure progress continues. By working together, we can create a sector that is not only inclusive but stronger, more innovative, and better equipped to tackle environmental challenges for all.

ROADMAP TO JUSTICE 1 2 3

PHASE 1: FOUNDATION ACTIONS (YEAR 1)

PHASE 2: DEEPENING THE WORK

(YEARS 1-3)

PHASE 3: INTEGRATION & CO-OWNERSHIP

PHASE 1: FOUNDATION ACTIONS 1

CREATING FAIR ACCESS TO GREEN JOBS

Practical

Solutions

Integrate free driving lessons and access to vehicles into early-career roles.

Partner with jobcentres, local authorities, or social funds to remove transport barriers — particularly in rural, field-based, or outreach roles.

Goal:

Remove entry barriers and build equitable routes into environmental careers for underrepresented groups.

Diverse applicants can access jobs without needing unpaid experience, insider contacts, or specific academic backgrounds.

What this looks like:

Roles are promoted widely, with clear, inclusive language and transparent selection criteria.

Career development and progression are supported for all staff.

Offer paid internships, traineeships, and apprenticeships, especially for those from marginalised communities.

Remove unnecessary degree requirements where experience is equivalent.

Use blind recruitment and diverse hiring panels.

Partner with community groups, schools, and colleges to create outreach and mentoring programmes.

Clearly outline progression pathways in job descriptions and staff inductions.

I d e as

Partner with Welsh universities (e.g. Bangor, Aberystwyth) to highlight diverse students and researchers already engaging in climate, marine, and biodiversity work.

Wal e s

STRENGTHENING INCLUSION IN YOUR ORGANISATION

Goal:

Foster safe, supportive, and diverse work cultures where everyone can thrive.

What this looks like:

Staff feel confident bringing their full selves to work without fear of exclusion, microaggressions, or bias. Managers model inclusive behaviour and actively challenge discrimination.

Diverse identities are respected, celebrated, and reflected across the organisation.

Practical & Innovative Solutions

Develop peer support and identitybased affinity groups: Create safe internal networks for staff with shared lived experiences (e g� LGBTQ+, global majority, disability, working-class) to connect, advise leadership, and support wellbeing�

Decentralise recruitment: Accept non-standard applications (e g� video), recruit beyond traditional networks, and value lived experience alongside formal qualifications.

Create a “DEI Innovation Fund” within the organisation: Invite staff to pitch small-scale projects that improve inclusion, with ring-fenced internal funding to test and scale what works�

Appoint an Inclusion Champion within senior leadership: Ensure DEI is not siloed within HR but held at the top, with clear accountability in performance reviews and board oversight

Offer paid internshipto-employment pathways for underrepresented groups: Design roles that guarantee progression from a supported internship to full employment — with training, mentorship, and cost-of-living support built in

Map access to green workspaces and community links: Audit whether your sites, field offices, or green spaces are physically and culturally accessible to all — and build local partnerships to open them up�

COMMUNITY

ENGAGEMENT & ACCESS TO NATURE

Practical & Innovative Solutions

Expand access to green spaces and involve communities in shaping environmental initiatives.

What this looks like:

Goal: Events and initiatives are physically, financially, and culturally accessible to all. Communities feel welcomed and included in activities — not treated as an afterthought or labelled as “hard to reach”. Programmes are co-designed with local people, not just delivered to them.

Offer nature-onprescription and wellbeing referrals: Partner with local health boards and GPs to allow people to access green engagement activities as part of mental health or wellbeing support�

Pay community members as cocreators, not just participants: Recognise the time, knowledge, and lived experience of community collaborators through stipends or short-term contracts Build equity into the engagement process

Embed nature activities in familiar, everyday settings: Run pop-up events in car parks, high streets, schools, or community cafés — bringing nature to people instead of expecting them to travel to it�

deasforLocal

Connection

in W a sel membersFeaturecommunity from North WalesgroupsAfricaSocietyorsimilar alreadyinvolved in localconversations.DEI-environment

Create mobile green space hubs: Use vans, trailers, or pop-up units to deliver nature-based activities, workshops, and access to kit (e g� binoculars, waterproofs) to rural or urban doorstep settings�

Co-design citizen science and local monitoring projects: Train local people to monitor biodiversity, water quality, or air pollution in their area — and feed into real decision-making� Build ownership and trust through shared data and storytelling

Provide free skills training tied to local jobs in nature: Use community programmes as stepping stones to green jobs, offering things like first aid, bushcraft, habitat surveying, or digital mapping skills — linked to local employment pathways

Celebrate local culture in nature spaces: Include art, music, food, and storytelling relevant to the community to make events feel like their space — not an outsider’s programme�

Create family-first policies for events: Offer child-friendly activities, breast/ chest-feeding spaces, quiet zones for neurodiverse attendees, and free transport or minibus pickups from local hubs�

REPRESENTATION & ENVIRONMENTAL STORYTELLING

Goal:

Ensure diverse voices and experiences are visible in environmental education, media, and decisionmaking.

What this looks like:

Campaigns, reports, and outreach reflect the true diversity of communities affected by environmental issues — not just those traditionally involved in the sector.

People of colour, disabled people, LGBTQ+ voices, and others are visible and valued in leadership, media, and storytelling roles.

Environmentalism is explored through multiple lenses — including justice, wellbeing, culture, urban space, and lived experience — not just wilderness and conservation.

Practical & Innovative Solutions

Build partnerships with ethnic minority and disability-led media outlets: Don’t just rely on mainstream or sector channels — collaborate with community radio, YouTube creators, newsletters, or social enterprises that already reach diverse audiences�

Host community storytelling takeovers: Hand over your social media or campaign platforms to community groups or individuals for “takeover days” where they share what environmentalism

Train and mentor community storytellers: Set up mentorship programmes to support emerging creators — especially from working-class, racialised, or rural backgrounds — to build confidence, technical skills, and platforms�

Redefine what counts as ‘environmental’: Include stories about urban gardening, food access, energy poverty, cultural land practices, or migrant farming — reflecting a fuller spectrum of environmental justice

Include bilingual, culturally resonant storytelling: In Wales, this could mean supporting stories in Welsh, English, and other community languages, and reflecting the specific cultural landscapes of diverse Welsh

Fund and commission first-person narratives: Pay people from underrepresented backgrounds to tell their own environmental stories — through blogs, short films, zines, audio diaries, or visual art� Avoid extractive storytelling�

Create inclusive media guidelines: Develop internal guidance to ensure all comms and campaigns are reviewed for bias, tone, and representation — ideally co-created with staff from underrepresented groups

Use participatory photography and film: Put the camera in participants’ hands — let them document their connection with nature and place, supported by training, resources, and editing help�

REPRESENTATION & ENVIRONMENTAL NARRATIVES

Dr Vandana Shiva - eco-activist, writer, food sovereignty advocate, philosopher of science and physicist She has written over 20 books Shiva works to protect traditional agricultural knowledge, indigenous seed diversity

Nadeem Perera - a wildlife TV presenter, author, activist and bird watcher Cofounder of Flock Together

Decolonise environmental education by including Indigenous knowledge and diverse conservation leaders.

Challenge stereotypes of environmentalists by promoting diverse role models in media and public campaigns.

Ensure media and outreach efforts reflect the diversity of people engaged in environmental work.

Highlight POC leadership in environmentalism, ensuring decision-making reflects diverse communities. Showcase inclusive environmental movements and history beyond the Western lens.

Dominique Palmer - Climate activist and writer- Palmer advocates for marginalised communities and educates about intersectionality within her activism, campaigning for legislation change and was part of organising the UK’s first Black Ecofeminist Summit and has spoken in UN climate change conferences

Chico Mendes - Was a Brazilian rubber tapper, environmentalist and trade union leader who fought to preserve the Amazon Rainforest and advocate for the human rights of indigenous people

Nemonte Nenquimo - is an Indigenous activist, author and member of the Waorani Nation from the Amazonian Region of Ecuador. She is the first female president of the Waorani of Pastaza and co-founder of the Indigenous-led nonprofit organisation Ceibo Alliance. Working to protect the Amazon from oil extraction deforestation and fighting for legislation to protect Waorani land

INSPIRATION: WHO IS DOING GREAT WORK IN

THIS SECTOR ALREADY?

Colourful Heritage & NatureScot Traineeships (Scotland)

Providing paid placements, qualifications, and mentoring to young people from ethnic minority backgrounds to build careers in nature and conservation.

Black2Nature (UK-wide)

Founded by birdwatcher and activist Dr. Mya-Rose Craig (Birdgirl)

Running nature camps and safe spaces for young people of colour to experience the outdoors, tackle racism in the sector, and advocate for greater visibility and leadership.

Generation Green (England)

Led by: The Access Unlimited coalition (including YHA, Scouts, Outward Bound Trust, and others)

Delivering inclusive green job training, residential experiences, and placements to over 100,000 young people, many from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds.

Action for Conservation (UK)

Offering youth mentoring, school programmes, and leadership camps specifically designed to connect marginalised young people to environmental action. Their WildED and Penpont Project empower youth as climate leaders.

Flock Together (UK/Global)

A collective reconnecting Black and Brown people with nature through birdwatching and community walks, challenging the assumption that nature spaces are white-dominated and fostering joy in the outdoors.

Muslim Hikers (UK)

Organising inclusive hikes and outdoor events for the Muslim community, breaking down cultural and safety barriers to accessing national parks and rural landscapes.

Diverse Sustainability Initiative (UK)

IEMA and a coalition of sustainability professionals

Working to diversify the sustainability sector, improve representation in leadership, and tackle recruitment and retention barriers through pledges, data, and industry guidance.

ETHNICALLY DIVERSE ENVIRONMENTALISTS FROM WALES & THE UK

Jamal Ajibade

London, UK

Youth climate justice activist with Nigerian heritage.

Known for her work with Extinction Rebellion and campaigning on climate and racial justice, often advocating for emotional resilience and community care in activism.

Intern at Synchronicity Earth, with a focus on conservation, youth engagement, and creating accessible environmental careers for underrepresented groups.

Shares lived experiences as a young Black man in the environmental sector, and is an advocate for systemic inclusion.

Environmental educator and advocate, co-founder of Nature Is A Human Right, and speaker on environmental justice and equity.

Focuses on ensuring everyone has access to safe, green spaces and is visible in media campaigns and sector panels.

Aneesa Khan

Climate justice activist and writer of Indian heritage, involved in Loss and Damage advocacy and environmental equity work.

She bridges climate science and social justice, representing youth at UN climate negotiations.

Bristol, UK / WelshBangladeshi heritage

A prominent young ornithologist, activist, and founder of Black2Nature, which organises nature camps for young people of colour.

She was the youngest person in the UK to receive an honorary doctorate (from Bristol University) for her work on diversity in conservation.

Strong links to both Wales and wider UK environmental policy discussions.

Tayshan Hayden-Smith

London, UK

Founder of Grow2Know, a community gardening initiative born after the Grenfell tragedy.

Uses urban

greening to engage underrepresented communities, particularly Black and working-class youth.

Advocates for racial justice, nature connection, and inclusive environmental design.

Leyla Hussein OBE

Somali-British health activist with environmental justice interests

While primarily known for campaigning around mental health and gender-based violence, she has also spoken on the intersection of environmental and racial justice, especially around access to green space for healing.

Artist and environmental storyteller based in the UK

Works at the intersection of art, nature, and climate justice, especially around decolonising environmental narratives. Projects include immersive storytelling and community co-creation on environmental themes.

Daze Aghaji

Johnathon Mbuna

Maya Chowdhry

Dr. Mya-Rose Craig (Birdgirl)

This section moves us from fair access to shared power — asking not just who’s in the room, but who sets the agenda.

PHASE 2: DEEPENING THE WORK

FROM INCLUSION TO TRANSFORMATION

Many organisations stop at awareness training, diverse imagery, or inclusive events — all important first steps. But if we stop there, we risk reinforcing the very systems we aim to change.

Deepening the work means shifting from inclusion to powersharing, co-design, and structural change. It’s not just about who is in the room, but who sets the agenda, who holds the budget, and who defines success.

This section invites you to look beyond internal fixes and shortterm projects — and begin building models that embed justice, challenge hierarchy, and create space for shared leadership and lived experience to shape outcomes from the start. If Phase One helped organisations open the door, Phase Two is about moving out of the way, and building the new system together.

1. Reframe Inclusion as Power-Sharing, Not Outreach move From: “How do we invite people in?”

To: “How do we share power, decision-making, and resources?”

2. Decolonise Environmental Practice

From: “Teach diverse groups about nature.”

To: “Acknowledge, value, and uplift Indigenous and migrant environmental knowledge.”

3. Build Economic Justice into Environmental Careers

From: “Open volunteering opportunities.”

To: “Remove structural barriers to environmental work.”

What this means in practice:

Example: Set up a co-creation panel for your next project that includes local Somali, Afro-Caribbean, or Eastern European residents who co-design the activities and hold equal voting power on budget and delivery.

Examples of what this means in practice

Host workshops or storytelling walks where individuals can share how their cultures relate to land, water, and seasons — e.g. cultural planting rituals, nature-based foods, or oral histories.

Add migrant histories to place: e.g. create a Bangor “River Memory” trail featuring stories from AfroCaribbean residents living near the Cegin or Menai rivers.

Example: Allocate £5,000 micro-grants annually for grassroots groups (e.g. a refugee gardening group or Muslim hiking club) to run their own nature-based activities in their community’s style.

Example: When writing funding bids, include named community groups as delivery partners, and share decision-making on how funds are used.

Audit your signage, teaching materials or interpretation boards: are they English-only and Eurocentric, or do they also include multilingual, diasporic, or decolonial perspectives?

Examples of what this means in practice:

Fund paid green traineeships for young people of colour from towns like Wrexham, Llanelli or Holyhead — not requiring a car, degree, or unpaid work experience.

Partner with ethnic minority organisations (e.g. EYST, BAWSO, Race Council Cymru) to co-develop entry routes into river conservation or community growing, offering kit, travel support and work placements.

Provide driving lessons and language support for trainees who speak English as a second language, especially around acronyms and specialist technical language.

4. Redesign Engagement Around Belonging

5. Hold the Sector and Your Organisation Accountable

From: “We did our DEI training.”

From: “Invite diverse communities to our events.”

To: “Design events where people feel they belong, without needing to assimilate.”

Examples of what this means in practice

Work with community leaders in Wales to codesign women-only walks, halal campfire meals, or multilingual river cleanups.

Plan nature events at trusted cultural centres (like the Bangor African & Caribbean Centre or Newport Yemeni Centre) and let them lead invitations.

Address cultural safety head-on: ensure facilitators are trained in anti-racism, provide prayer space or halal food, and be explicit that discrimination won’t be tolerated.

To: “We report publicly on who holds power — and shift it.”

Language Equity Audit Prompt

Prompting teams to reflect on everyday language that may produce power imbalances.

In practice, this looks like:

Publish an annual racial equity dashboard: % of staff, trustees, volunteers, and trainees from racially minoritised backgrounds in your organisation.

After events or projects, collect anonymous feedback forms in multiple languages asking: “Did you feel welcome?” “Did this reflect your identity?” “What’s missing?”

Build an alliance of Welsh eNGOs committed to racial justice — sharing data, holding each other accountable, and pushing funders to support long-term inclusion work (not just 6-month projects).

Do we say “hard-to-reach” rather than “historically excluded”?

Do we name racism or hide behind vague terms?

Are we unintentionally centering whiteness in our storytelling?

Why it works: Language shapes culture

This

section

moves

us from fair

access to shared power — asking not just who’s in the room, but who sets the agenda.

PHASE 3: INTEGRATION & CO-OWNERSHIP 3

REBUILDING THE SYSTEM - TOGETHER

Phases One and Two focus on making space — first through inclusion, then by sharing power.

But real, lasting change happens when diverse communities don’t just access or influence the sector — they help shape, run, and redefine it.

Embedding justice into the core of environmental organisations

— not as a bolt-on, but as a shared blueprint.

Shared Leadership Structures

Move beyond tokenism to co-governance.

Leadership must reflect the full breadth of communities you serve — and share real power.

Example:

Example: A national Welsh nature charity adopts a joint leadership model, where racially minoritised leaders are recruited through an equity-centred process, supported with long-term mentorship and decision-making power. The charity also embeds an Equity Advisory Board with voting rights on strategy, resourcing, and accountability.

This ensures equity isn’t siloed in HR or outreach — it’s structurally built in.

Phase Three is about deep integration: embedding racially and ethnically diverse people, cultures, and knowledge into the heart of the environmental movement in Wales. It’s a shift from inviting others in to co-owning the system together.

Integrated Programmes and Place-Making

Design from the ground up, not bolted on after the fact.

True integration means involving communities from day one — in setting priorities, shaping language, and co-owning outcomes.

Example:

A wetland restoration in rural Ceredigion is co-designed by local farmers, Somali growers, and Welsh-speaking youth. The project reflects multiple relationships with land — combining ecological science, migration histories, and cultural planting practices into a shared vision.

Embedding justice into the core of environmental organisations

— not as a bolt-on, but as a shared blueprint.

Research Reference List

Agyeman, J. (1989). Black people, white landscape: The impact of race and class on environmental quality in Britain. Built Environment, 15(1), pp. 38–43.

Agyeman, J. (1990). Black people in a white landscape: A study of the relations of black people to the British countryside. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 33(4), pp. 481–492.

Friends of the Earth. (2020). England's Green Space Gap. [Online] Available at: Body Green Space Index. (2024). The State of Green Space in Wales. Fields in Trust. [Online] Available at: Body

Morris, N. (2003). Black and minority ethnic groups and public open space: Literature review. Edinburgh: OPENspace Research Centre.

Nelson, R.G., Rutherford, D.L., and Harwood, S.A. (2017). Mentoring and Retention of Underrepresented Groups in Ecology and Environmental Fields. Ecology and Society, 22(4), 20.

Office for National Statistics. (2020). Access to gardens and public green space in Great Britain: 2020. [Online] Available at: Body

Platts, L. (2015). Ethnicity and Family: Relationships within and between ethnic groups. UK Government Ethnicity Facts and Figures. Policy Exchange. (2017). Academic Diversity: Perspectives from the Geosciences. [Online] Available at: Body

Primack, R.B., Martine, C.T., and Losos, E.C. (2023). The Equity and Inclusion Crisis in Ecology: How to Recruit and Retain a Diverse Workforce. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 21(1), pp. 4–11.

Ramblers/YouGov. (2020). Access to Green Space Survey Results. Ramblers Association.

Robinson, J.M., Jorgensen, A., Cameron, R., and Eames, C. (2023). Barriers and enablers to green space use for ethnic minority groups: A review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 81, 127837.

The Community Green Report. (2004). What the public tells us about their local green spaces. CABE Space.

The Race Report. (2023). Ethnic Diversity in the Environmental Sector. [Online] Available at: Body

Urban Green Nation. (2010). Building the evidence base. CABE Space.

Inclusive Employment & Career pathways Community Engagement Access to Nature Workplace Culture

No degree required for some roles

Collect demographic data (anonymously) from applicants and staff to track representation and identify gaps