10 minute read

7.6 Different perspectives about the distribution of income and wealth

In some cases, a poor ‘work ethic’ or attitude results in individuals being unable and or unwilling to gain or keep their job. The problems could be rudeness or a negative manner, lateness in arriving for work, a lack of effort, or unsatisfactory dress and personal appearance. This can make some people less employable and can lead to their exclusion from the labour force. This then leads to lower incomes and material living standards.

Of course, some individuals simply do not want to spend their life working and earning money — achieving a better work–life balance is an important consideration for them.

Advertisement

Rapid inflation causes income inequality Inflation (i.e. when most consumer prices are rising) can also cause inequality in both income and wealth, usually in favour of the better-off sections of society. For example, speculators buying assets like shares and property when prices are low — and selling them when inflation causes prices to rise — often do relatively well from inflation (as in the middle to late 2005–08, and 2021–22 when property prices rose significantly). Their share of both the income and wealth cakes tends to increase, relative to others. Typically, these people are the rich, with sufficient savings or credit rating to permit speculative activities. By contrast, ordinary working families and retirees on relatively fixed incomes often find that their wages and incomes rise less quickly than prices. Paying bills and buying food become more difficult. In addition, for young people, purchasing a house is less affordable because of higher property prices and interest rates on money borrowed from the bank. This adds to income and wealth inequality and erodes living standards. Overseas economic conditions cause income inequality Variable economic conditions overseas can cause income inequality. When there is strong economic growth abroad among our trading partners (e.g. China and USA), Australian mineral exporters and their workers find that rising commodity prices and sales lead to higher incomes, often faster than others in the community. For instance, the recent strong demand for mineral and rural commodities from abroad in 2021–22 saw incomes in these sectors rise strongly. In contrast, the falls recorded during the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–21 saw a fall in the incomes of some. Declining unionism has increased inequality Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic decline among workers in union membership. Figure 7.22 shows that following a peak of 51 per cent in 1976, the overall (the total of women and men) unionisation of the labour force has fallen to around 14 per cent by 2020. This means that when wage rises are being negotiated between workers and their boss, there is now less protection of workers from wage exploitation and unsafe working conditions. Even so, it is likely that union membership still affects the income difference between unionised and non-unionised workers. There is some evidence that pay rises are faster in occupations that are more highly unionised, since this shifts the balance of power in wage negotiations in favour of workers. The growth of technology is increasing inequality Increasingly, the application of technology, computers, robotics and automated processes are performing lots of tasks in manufacturing, banking, finance, packaging and warehousing that were once done by employees. This has reduced the number of staff required and has eliminated many boring and repetitive jobs. The growth in artificial intelligence (AI) is further accelerating this trend. While technology destroys some jobs, it creates others, usually for workers with greater skill, but not always at the same rate or in the same industry. As a result, unemployment may rise amongst the unskilled and/or UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS the growth in wages may slow down, as seen recently. Because the application of technology is controlled by business owners (i.e. those who operate capital resources), this tends to increase the profit share of Australia’s income cake that goes to business owners. Figure 7.23 supports this idea and shows that, over time, the share of the income cake going to ordinary employees has fallen dramatically. On the other side, there has been a rise in the share of GDP or income in the form of profits going to business owners.

FIGURE 7.22 Trends in Australia’s number of union members and membership rate as a percentage of all employees

Trade union membership (%)

Source: ABS, Trade Union Membership, see https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/trade-unio n-membership/latest-release. FIGURE 7.23 How Australia’s national income is shared between workers and business owners Sahe of income as percentage of GDP Trade union membership by sex 1974–75 2019–20

Changes in income shares as a percentage of GDP going to employees as opposed to business owners-Australia 50 40 30 20 10

Wages share as a percentage of GDP (compensation for labour) Profits share as a percentage of GDP (gross operating surpluscompensation for owners of capital) Linear (Wages share as a percentage of GDP (compensation for labour)) Linear (Profits share as a percentage of GDP (gross operating surpluscompensation for owners of capital))

57.6 22.4

47.9 36.8 60 0 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Source: Data derived from RBA, see https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/?v=2022-0412-15-55-46#output-labour.

1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Men (pre-2004) Women (pre-2004) Total (pre-2004)In addition, the application of technology has meant that the income gap Men (2004+) between skilled workers who use

Women (2004+) Total (2004+) technology (where there is an increasing demand but a limited supply) and those that are unskilled has continued to widen.

Students, these questions are even better in jacPLUS

Receive immediate feedback and access sample responses Access additional questions Track your results and progress

Find all this and MORE in jacPLUS

7.5 Exercise 7.5 Quick quiz 7.5 Exercise 1. a. Clearly explain any three of the following causes of inequality in Australia’s distribution of income, consumption and goods and services: (6 marks) • high unemployment and/or low hours of work • high inflation rates • stronger or weaker economic conditions overseas among our trading partners • inheritance • some government policies like tax concessions often used by higher income earners to reduce their actual tax rate. b. In an unregulated or free labour market, carefully explain why there are often wage differences between occupations. (4 marks) c. The forces of demand and supply in the labour market play a big part in explaining inequality in Australia’s weekly wages. From the following list, select one high- and one low-income occupation (two examples in total): • Basketball player, Andrew Bogut, (reportedly earned $16.2 million) • The manager of the National Australia Bank (reportedly paid over $5 million per year) • A crewmember/worker at McDonald’s (paid around $18 per hour) • A farmer (average income $278 000 in 2021–22) • A childcare worker or nurse in a public hospital • A successful heart surgeon (average income around $380 000 per year) • Tennis player, Ash Barty (reported income of $13.1 million) • A brilliant computer engineer and designer • A person with a poor ‘work ethic’ • Tennis player, Roger Federer (reported gross income of over $90.6 million). Draw and label a D–S diagram for the two examples selected. Referring to a range of specific demand or supply factors in the labour market, explain the most likely reasons why income is either relatively high or low for that occupation or person. (4 marks) 2. Examine the four images shown in figure 7.24 before answering the questions that follow: a. Explain why unemployment by the main household earner is far more likely to cause poverty than households where the main income earner is employed. (2 marks) b. Explain why children in sole parent households are far more likely to be living in poverty than in couple families. (2 marks) c. Explain why households dependent on government welfare benefits are far more likely to be living in poverty than households where the main income earner is employed. (2 marks) UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

d. Explain why sole parent households, where the main income earner is female, are far more likely to be in poverty than households where the main income earner is male. (2 marks)

FIGURE 7.24 Factors affecting Australian poverty rates

People who are unemployed are at most risk of poverty Children in sole parent families

Main household earner is unemployed 66% of households are in poverty Main household earner is employed 9% of households are in poverty Children in sole parent families are 3 times more likely to live in poverty than children in couple families 44% poverty rate 13% poverty rate

Social security payments Households relying on social security payments are five times more likely to experience poverty

Income source is

Govt payments 35% of households are in poverty Income source is Wages/salaries 7% of households are in poverty Gender gap Among sole parent families where the main earner is female, the rate poverty is 37% compared with 18% in sole parent families where the main earner is male. 37% poverty rate

18% poverty rate Source: ACOSS, Poverty and Inequality, see https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/poverty/#:~:text=Our %202020%20report%20Poverty%20in,424%2C800%20young%20people%20(13.9%25). Fully worked solutions and sample responses are available in your digital formats. Resourceseses Resources Weblinks Income and wealth inequality Labour market Where did a million Chinese millionaires come from? The manners and morals of high capitalism UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS Why we look down on low-wage earners Gina Rinehart: The power of one (Four Corners) The Fringe Dwellers Centrelink 32 Jacaranda Key Concepts in VCE Economics Units 1 & 2 Twelfth Edition

7.6 Different perspectives about the distribution of income and wealth

KEY KNOWLEDGE

• the different perspectives of households (consumers and workers), business, government, and other relevant economic agents regarding the selected economic issue

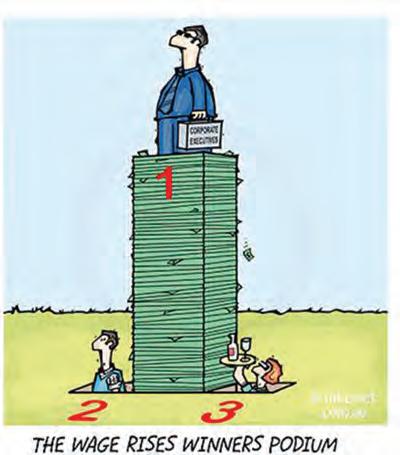

Source: VCE Economics Study Design (2023–2027) extracts © VCAA; reproduced by permission. What is the ideal distribution of income and wealth? Now that’s a tough question! Opinion is widely split about how income and wealth should be divided. On the one hand, some feel greater equality or fairness is a good thing, while others believe that inequality can be beneficial by creating financial incentives to propel efficiency and effort. As economic agents, people and groups have different viewpoints. For instance: • As an employee, you might feel that wages are too low and that the profits are unfairly high, allowing business owners to enjoy a lifestyle that can only be a dream for others. • As a business owner, perhaps you would like to pay staff less to cut costs, improve your international competitiveness, and boost returns. • As a consumer, you probably like cheap goods, even if this requires depressing wages and profits. • As a government facing periodic elections, you realise that it isn’t possible to keep everyone happy all of the time. Cutting taxes to make it fairer for one group unfortunately reduces the funds available for other purposes, like paying for welfare, education, housing, health or infrastructure. Your perspective about whether more equality or inequality in distribution of income and wealth is good or bad partly depends on your value or opinions about what you see as fair or unfair. Interestingly, a recent survey about the issue of income distribution found that 92 per cent of Australians believed that nobody should go without access to basics like food, healthcare, and power, and that nearly 80 per cent felt that it was up to the government to ensure people have enough money for basic accommodation and food. In other words, most Australians believe that too much inequality is a bad thing and that governments need to step in with appropriate policies, to help promote greater fairness and equity. The reality is that there will always be some inequality in the distribution of income and wealth. Indeed, most economists believe that a bit of inequality is good and in fact essential in our market economy. It creates incentives for the price system to efficiently allocate resources between different uses. However, opinion is divided about how much inequality is ideal.

FPO In this section, we are going to investigate a couple of these perspectives and examine why some inequality can have both good and bad effects on society’s wellbeing. Figure 7.25 sums up the opposing viewpoints or perspectives about the negative and positive effects of inequality for individuals, society, and general living standards. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS