13 minute read

6.6 Different perspectives about the issue of international trade

TABLE 6.4 Some factors that can change the conditions of demand and supply and hence the price of the A$ in the foreign exchange market

Three factors that can affect the level of credits or receipts for exports, changing the demand (D) of the A$ and hence the exchange rate Three factors that can affect the level of debits or payments for imports, changing the supply (S) of the A$ and hence the exchange rate

Advertisement

1. Changes in overseas rates of economic growth (e.g. amongst our trading partners China, USA) affect sales of Australian exports, and hence the D for the A$ and the exchange rate. 1. Changes in Australia’s rate of economic growth affects the value of our spending abroad on imports. This alters the S of the A$ and hence the exchange rate.

2. Changes in consumer and business confidence overseas affect sales of Australian exports, and hence the D for the A$ and the exchange rate. 2. Changes in Australia’s consumer and/or business confidence affect spending on imports. This alters the S of the A$ and hence the exchange rate.

3. Changes in the selling price of Australian-made goods and services, perhaps due to higher or lower production costs or efficiency, alters the international competitiveness or attractiveness to consumers of Australian exports. This affects the D for the A$ and the exchange rate.

3. Changes in the Australian government’s spending on imported defence equipment and in levels of foreign aid, alter the S of the A$ and hence the exchange rate. Depending on whether the exchange rate for the $A rises or falls has a huge impact on the value of Australia’s exports and imports of goods and services (and the trade balance). Figure 6.13 shows recent changes in the value or price of one A$ against the US$, the yen and the euro.

FIGURE 6.13 Recent changes in the value of one A$ when swapped for the US$, the yen and the euro in the foreign exchange market Australian dollar yen 200 Yen per A$ (LHS) 150 US$ per A$ (RHS) 100 50 1987 1994 2001 2008 2015 2022 * ECU per A$ until 31 December 1998.

Source: Bloomberg

0.40 0.80 1.20 1.60 US$, euro Euro per A$* (RHS) UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Source: RBA Chart Pack, see https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/exchange-rates.html.

Referring to figure 6.13, notice that following a mostly higher $A in 1984, its value fell or depreciated towards 2001. Then there was an appreciation and another peak in 2013, followed by generally lower levels since.

You might now wonder whether it is better for a country to have a high or low exchange rate for international trade. The answer depends on who you are. • For an exporter: ◦ A lower exchange rate makes Australian goods and services relatively cheaper and hence more internationally competitive and attractive for overseas buyers. This boosts sales, AD, GDP, employment ◦ and incomes. A higher dollar makes it tougher for exporters to sell their goods and services because they are dearer to overseas consumers. This slows sales, injections, AD, GDP, employment, and incomes. • For an importer: ◦ A lower exchange rate makes imports dearer for us to purchase and our currency will not go as far. This cuts our purchases and spending on foreign goods and services, and tends to boost AD, GDP, ◦ employment, and incomes. A higher dollar makes imports cheaper and more attractive to Australian consumers. Being a leakage, higher imports tend to slow AD, GDP, employment, and incomes.

As a general rule, exporters (at least those who don’t need to purchase imports of goods or services from overseas to enable production) often prefer a lower exchange rate, while importers of goods and services from overseas tend to fancy a higher exchange rate. Put another way, a weaker A$ tends to strengthen the balance of trade, whereas a higher A$ tends to weaken the balance of trade. 6.5.2 The level of economic activity and inflation both locally and overseas affect the value of exports and imports The level of economic activity (i.e. the change in production and sale of goods and services) and inflation, both in Australia and overseas, can affect the value of our exports and imports. • The level of economic activity in Australia mostly affects the value of our spending on imports. ◦ When Australia’s economic activity is rising due to generally stronger aggregate demand factors such as consumer and business confidence and increases in disposable income, there is more spending on imports of goods and services (e.g. luxury cars, equipment, overseas holidays, appliances). In addition, because consumer prices also start to rise more quickly, locally made goods and services become relatively less attractive than those from overseas. This also increases imports. For these reasons, higher levels of economic activity tend to weaken our trade balance. ◦ In contrast, when domestic economic activity slows due to weaker local aggregate demand factors, spending on imports slows. This tends to strengthen the trade balance. • The level of economic activity overseas, especially amongst our trading partners (China, USA, Japan), affects their spending on our exports: ◦ When economic activity is stronger abroad and their output and inflation rate is rising, overseas consumers tend to buy more Australian exports of commodities and services. This causes our trade balance to strengthen. ◦ However, when economic activity internationally slows and output is cut, our export sales decline. This weakens our trade balance. 6.5.3 The level of international commodity prices received for our exportsUNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS Australia is a large exporter of commodities including minerals and rural products. The prices that are received and paid for these reflect global conditions of demand and supply in various markets. When there is a global market shortage, commodity prices rise, while market gluts depress prices.

• Higher commodity prices for the goods Australia sells overseas (e.g. gold, iron ore, gas, wool and wheat), due to strong global demand relative to supply, mean that the value of our exports rise, bolstering the trade balance. • In contrast, lower commodity prices received, due to weaker global demand relative to supply, cause the value of our exports to fall. The trade balance becomes less favourable.

Figure 6.14 shows the changing level of commodity prices received for commodity exports of Australian iron ore and coal.

FIGURE 6.14 Recent changes in global commodity prices received for Australian exports Iron ore (LHS) 2015 Thermal coal (LHS)

Bulk commodity prices Free on board basis Coking coal (RHS)

* Iron ore 62% Fe fines index; Newcastle thermal coal and premium hard coking coal.

Average Australian export price Spot price* 2022 2015 2022 2015 2022 100 200 300 US$/t 0 150 300 450 US$/t Source: RBA Chart Pack, see https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/commodity-prices.html. Notice the general spike in commodity prices during 2021–22. This helps to explain Australia’s large trade surplus in recent times. 6.5.4 Severe weather events and pandemics here and overseas affect the value of exports and imports Over recent years, Australia has not been alone in experiencing more frequent and severe weather events linked with climate change. In addition, there has been the COVID-19 pandemic. These have impacted Australia’s exports, imports and trade balance. • For example, as less favourable aggregate supply conditions, recent cyclones, floods, drought, fires, and the pandemic have all reduced Australia’s productive capacity and potential level of exports. Farms and businesses were destroyed. The pandemic health emergency and the associated lockdowns caused labour shortages, limiting output. In addition, borders were closed to international tourists and overseas students, reducing exports of services. • However, when conditions are more favourable due to beneficial weather conditions, exports tend to rise more quickly (although when our borders are open, more Australians holiday and travel overseas, increasing the value of imports). 0 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Students, these questions are even better in jacPLUS

Receive immediate feedback and access sample responses Access additional questions Track your results and progress

Find all this and MORE in jacPLUS

6.5 Quick quiz 6.5 Exercise

6.5 Exercise 1. a. Explain the term, exchange rate. In general terms, outline how Australia’s exchange rate is determined. (2 marks) b. Outline the effect on Australia’s exchange rate of an increase in the value of exports or credits. (2 marks) c. Outline the effect on Australia’s exchange rate of an increase in the value of imports or debits. (2 marks) d. Explain how each of the following international transactions would be likely to affect the exchange rate for the Australian dollar in the foreign exchange market, assuming all other things remained unchanged or constant: - Australia imports oil from Saudi Arabia - Australia sells natural gas to Japan. For each transaction shown in figure 6.15, complete and fully label the D–S diagram to hypothetically show the impact of the transaction by shifting the D line for the A$ (D1 to D2) or the S line for the A$ (S1 to S2), thereby bringing about a change in the equilibrium price or exchange rate (ER1 to ER2) and the equilibrium quantity of dollars traded (Q1 to Q2). Explain why the exchange rate changed in the way you have shown on the diagram. (4 marks) FIGURE 6.15 The impact of trade transactions on the exchange rate for the A$ D1

Q1 Q1

S1 ER for the A$ ER1 E1 D1 Quantity of A$

S1 E1ER1 Quantity of A$ ER for the A$ 2. a. Giving appropriate examples for Australia, define the term, commodity exports. (1 mark) Examine figure 6.16 showing an index that measures the average price of Australia’s commodity exports, before answering the questions that follow. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

FIGURE 6.16 Index of Australian commodity prices.

Index

RBA Index of commodity prices SDR, 2019/20 average = 100, log scale

135 Index 135

100

100 30 1992 1998 2004 2010 2016 2022 65 30 65 Source: RBA Chart Pack, see https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/commodity-prices.html. b. Explain how the peak in our export commodity prices in 2011–12 and the trough in 2015–16 would tend to affect Australia’s balance of trade. (3 marks) 3. Explain how severe weather events and the COVID-19 pandemic might affect Australia’s balance of trade. (2 marks) 6.6 Different perspectives about the issue of international trade KEY KNOWLEDGE • the different perspectives of households (consumers and workers), business, government and other relevant economic agents regarding the issue of international trade Source: VCE Economics Study Design (2023–2027) extracts © VCAA; reproduced by permission. Having some understanding of what international trade for countries like Australia involves, it is now time to look at the different views or perspectives about the issue. For example: • As a consumer, you probably enjoy having access to cheaper goods and services from overseas and a far broader product choice. • As a business owner, while you might benefit from being able to expand by selling goods and services overseas, you might not appreciate strong product and price competition from imported substitute products that squeeze your profits and may cause you to close down. • As a worker in an industry that faces strong competition from imports, you worry about your employer being forced to close because local production costs, including wages, are just too high relative to overseas. • As a government, you might be popular with consumers who want cheaper prices thanks to imports, but might also be unpopular with other voters who have lost their job when local firms close due to foreign competition. The point here is that people have different views about whether international trade is a good or bad thing and UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS whether it should be encouraged.

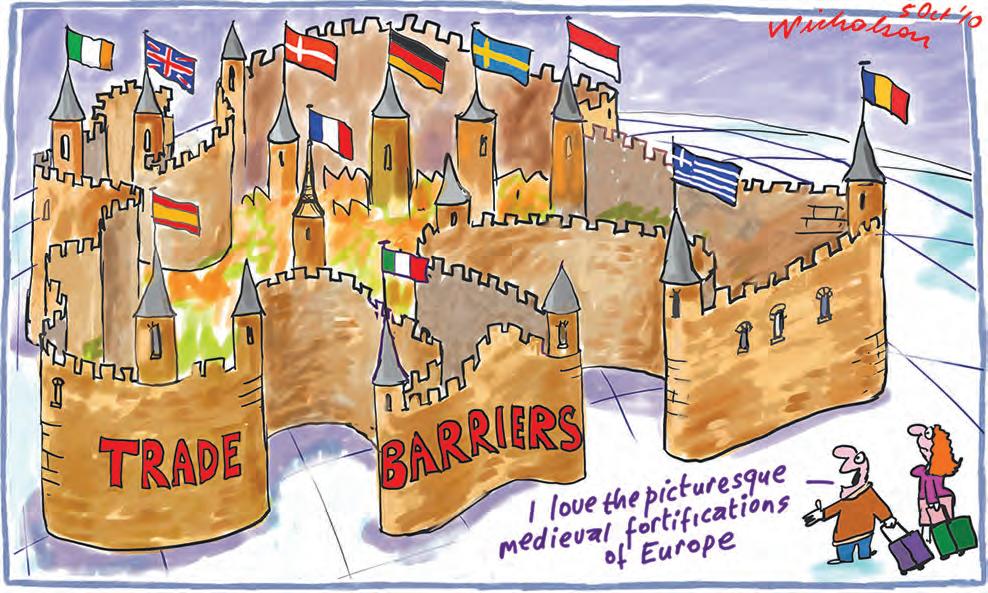

Over the years, economic debate has raged between two opposing viewpoints: • On the one hand, there are those who argue the benefits of trade liberalisation and free trade where there is little or no government protection of local industry from import competition. Most see this approach as a way of increasing efficiency in our use of resources and, thereby, increasing national production, employment, incomes and living standards. • On the other hand, there are those who believe in what is called, protectionism. Here, the government uses policies that deliberately restrict the level of foreign competition in local markets, so that firms and their employees can survive and be profitable. Table 6.5 sums up some of the main ideas behind these two opposing perspectives.

TABLE 6.5 Government policies towards international trade involving free trade or protectionism

Free trade — no government protection of local industry from imports Protectionism — government protection of local industry from imports

• There are no tariffs or taxes placed on imports coming into the country from overseas, designed to make imports dearer to local consumers. • High tariffs are placed on imports to make them dearer than the local goods. • There are no subsidies paid to local producers to help cover their costs so they can sell goods and services more cheaply. • Subsidies paid help local firms to cover some of their production costs so they can sell profitably at lower more competitive prices. • There are no import quotas limiting the volume of foreign goods permitted to enter the country so that consumers are forced to buy more locally made items. • Import quotas limit the volume of particular goods that can be imported so local consumers are forced to purchase more of the local product. • Many multilateral (involving many countries) and bilateral (usually between two countries) free trade agreements (FTAs) are signed to reduce or abolish tariffs on the movement of imports and exports between countries, so that the volume of two-way trade increases.

• No free trade agreements (FTAs) are signed. Interestingly, most governments around the world have now adopted economic policies that involve the liberalisation of trade and a gradual move towards free trade. Protection levels are now very low in most countries including Australia, where our average tariff rate on imports is less than 1 per cent. However, nations like the Solomon Islands, Palau and Bermuda have average tariff rates above 30 per cent. 6.6.1 One perspective: The advantages of free trade Supporters of trade liberalisation and the shift towards free trade, believe that businesses must be efficient and survive without special taxpayer-funded government support. For them, it’s more a matter of encouraging survival of the fittest, rather than having industries propped up on life support! Figure 6.18, sums up their four main arguments: Specialisation, greater efficiency, economic growth and incomes UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS Without protection, free trade means that resources will be allocated by market forces into areas of production where a business or a country is relatively most efficient and where production costs are relatively lowest. This means that different countries are encouraged to specialise in producing particular types of goods and services where they have a cost advantage, or at least where their costs disadvantage is least. Resources will thus be put to work in their most productive use. As a result of free trade, more output (GDP) will be produced from the same inputs, and hence incomes and material living standards should be higher.

FIGURE 6.17 Free trade involves no tariff barriers or other forms of protection for local industry. While free trade brings benefits such as cheaper goods, some groups, including farmers and local industries, see it as a threat to their survival.

FIGURE 6.18 Some advantages of free trade Advantages of free trade

Encourages specialisation, efficiency in resource allocation and faster rates of economic and income growth

Bigger markets for Australian exports can grow our international sales and trade Creates more jobs, employment and income, especially in the long term

Promotes lower inflation, increased purchasing power and greater consumer choice There are two types of cost advantage that are especially relevant to international trade, based on specialisation in production: 1. Absolute cost advantage. A country might have an absolute cost advantage where it is the cheapest or most efficient producer of a particular good or service in the world. For example, if South Korea is the cheapest or most efficient producer of cars in the world, it is said to have an absolute cost advantage UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS over other countries. It is likely that its car exports will sell very well indeed. Similarly, if Australia is the cheapest producer of iron ore and has an absolute cost advantage, Korean and other manufacturers would be keen to buy this from us. Both countries would benefit from specialisation in international trade since each has an absolute cost advantage in different areas of production.