20 minute read

3.3 The effectiveness of strategies used by government to influence consumer behaviour

• You see a sign on yummy doughnuts advertising them at 70 per cent off the recommended retail price. You immediately dive in and purchase a box of them thinking it’s too good to miss, irrespective of whether they were really worth the original exorbitant price.

In these examples, our perception of what constitutes good value has been changed by the way the options have been presented.

Advertisement

Resourceseses

Resources Weblink A Brief History of Nudge Overconfidence bias Some consumers subjectively believe they are better than they really are in spotting a bargain, winning a lottery, avoiding a risk, or making accurate estimations. They have an overconfidence bias in making good decisions. Behavioural economists sometimes attempt to measure this bias using experiments. They often ask participants to answer general knowledge questions and to rate how confident they are about the correctness of their answers on a scale of 1 to5, against the actual proportion of correct answers. Some studies report that the overconfidence bias is far more common amongst millennials born between 1980 and 1995 (65 per cent have a confidence bias), than amongst older baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 (23 per cent). The problem with this bias is that it can lead people to make non-rational choices based on limited knowledge and research that they may later regret. • For example, how often have you predicted that a homework task will take you less time to complete than it does? • Overconfidence can also lead to lots of optimistic people starting a business, despite the reality of much lower chances of success. • In driving a car, overconfidence leads to more accidents. • In finance, overconfidence can lead some investors to make riskier decisions with poorer outcomes than originally expected. Vividness bias Sometimes information presented in a striking way causes people to focus too much on one thing, rather than consider all the other options that potentially could be more beneficial and increase their utility or satisfaction. This is called the vividness bias and can lead to silly or irrational choices. • For example, using highly charged, persuasive or vivid language, perhaps even bold type on emails, or callouts on graphs and other data, can encourage people to make decisions that are not necessarily based on the complete picture or a consideration of all the facts. As a result, the choice made might not be the one that maximises wellbeing or self-interest. What about the common reaction to dramatic front-page headlines about shark attacks in Western Australia? As a result, some decide never to go swimming again at Torquay (Victoria). However, this could represent an incorrect assessment of the actual risk of attack during ocean swimming that is estimated by some to be about 1 in 37 50 000. An incorrect assessment may well deprive some of the joys of surfing. Similarly, heavily focussing on graphic headline reports of an aircraft crash can cause some people to never fly, even though one US study found that, on average, the chance of dying in a car accident is around 1 in 110 as opposed to a 1 in 9800 chance in an aircraft. Remembering a standout piece of information rather than seeking the bigger picture can distort decisions UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS people make and cause them to be substantially irrational. • Bias could also be the selective use of a vivid colour on an image or advertisement designed to focus consumer attention and encourage them to ignore or analyse the other possible options. As a result, the decision made might not maximise self-interest, satisfaction, and wellbeing.

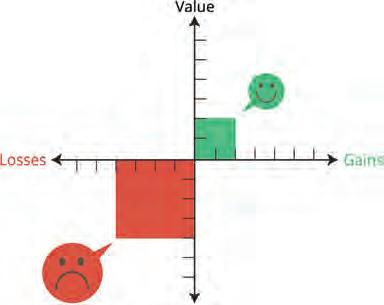

Short-term or present bias is often preferred Consumers often make choices by reference to the time period over which they gain a benefit or suffer a loss. Behavioural economic theory suggests that in making choices, people typically have a present bias. They seek immediate reward or gratification. Thinking about future consequences (good or bad) is often rated as much less important: • For example, would you rather receive $5 right now or wait two weeks and collect $10? Although using a longer-term time frame would produce double the benefit, this is often undervalued and, consequently, is less attractive as a choice. • Student attitudes to the completion of homework provide another illustration of the present bias. Studies have shown that many students do less homework than that needed to maximise their results. Often, this is because they disproportionately overvalue the short-term rewards like going out to a concert or party with friends and undervalue the impact this is likely to have on their career choices and employment prospects over the long-term (say in 5–10 years’ time). • This present bias has also been demonstrated in experiments with children and lollies. A child was told that they could have one lolly right now, but by waiting an hour they could have all five. It was found that most went for the immediate or short-term payoff, even though it reduced their overall gain and was not in their self-interest. Clearly, their choice represents an irrational decision. • Given the volatility of share market prices, investors with a short-term bias are more likely to face higher risks and make losses, than those with a longer-term view. In these cases, the decisions made are not altogether rational nor optimal. Risk or loss aversion bias Behavioural economics shows that people tend to place more importance on avoiding losses, than on making equivalent sized gains. In other words, people have a risk aversion bias and as some say, ‘losses loom larger than gains’. • As an example, pretend that there are two unmarked envelopes in front of you — one of which has $100 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS dollars in it and the other has nothing. You are offered a choice. You could select one of the envelopes and have a fairly good one in two chance of winning $100. Alternatively, you could receive a guaranteed $50 cash by not choosing either envelope. As an economic agent, which option would you go for?

• Another illustration can be found in the share market. While most investors would experience pleasure from making a capital gain of $1000 (i.e. when they sell their shares at a higher price than that at purchase), some research suggests that their pain or displeasure from the same-sized loss of $1000 is twice as great! In other words, this causes them to have a loss aversion thereby potentially reducing their returns. • A loss aversion bias could also mean that with government attempts to influence our behaviour, using disincentives and financial penalties for bad choices are likely to be more effective than rewards for good ones.

Narrative fallacy Consumers can be sucked into various scams, simply because of the plausible and impressive way information is presented, often ignoring the absence of a more detailed and analytic approach. The narrative fallacy occurs when decision makers put too much importance on the story or narrative, rather than cold hard and relevant facts. • As an example of this approach to decision making, some Australians have been persuaded to part with millions of dollars that disappear into a black hole, never to be seen again. This type of narrative is often applied to get rich quickly schemes, ways to avoid tax, and supposedly fail-safe strategies for making money by somehow beating the market. • After years in the doldrums with huge losses, a large clothing business uses media releases to publicise the arrival of its new CEO who comes with an impressive record of leadership success (but not mentioned in the hype that this was in a small engineering firm). Does this necessarily mean that her/his arrival will cause the clothing company to be successful as forecast in the media hype or spin? The nudge The nudge is an idea derived from behavioural economics. It is a gentle strategy that helps to steer people’s decisions or behaviour towards a predictable and wanted outcome, while still allowing consumers to have free choice. In this respect, the nudge clearly differs from more direct disincentives or punitive methods such as bans, fines and laws designed to punish people who fail to make a certain decision (e.g. punishing car drivers for using mobile phones when driving, or banning soft drinks at the school canteen). The nudge is often applied to help achieve predictable outcomes. For instance: • Lollies are sometimes displayed at eye level near the checkout queue in some supermarkets to prompt a purchase. • Automated mobile phone reminders are sent to prompt people that they have a doctor’s appointment coming up. • Free waste disposal vouchers are provided by councils to encourage people to clean up their backyard. • A default organ donation scheme is used in some countries to encourage donations by requiring people to opt out if they do not wish to participate, rather than having a default setting that involves an opt in decision. Opting-in will be less successful in solving organ transplant shortages for sick patients. This is because it takes time and effort to get out of the scheme, so more people just go along with it. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Artificial intelligence

Increasingly we see an expanded role of artificial intelligence (AI) in making decisions. For example: • There are driverless cars that can navigate with little or no passenger input. • Large-scale algorithmic share trading is now common. It involves computer codes and chart analysis to enter and exit share trades that are triggered by factors like price changes and the degree of volatility. While some commentators see this as a threat, other studies have concluded that carefully designed and tested AI can even improve the quality of decision making, simply because programs can factor in far more variables and thus help to overcome the bias and limitations imposed by bounded rationality in making economic choices.

Resourceseses Resources Weblinks Behavioural Economics: Crash Course A Brief History of Nudge Nudge, the Animation: Helping people make better choices Nudge Theory Explained with Examples Behavioural Economics Crash Course Nudging: The Future of Advertising Marginal Analysis and Consumer Choice Marginal Analysis, Roller Coasters, Elasticity, and Van Gogh: Crash Course 3.2 Activities

Students, these questions are even better in jacPLUS

Receive immediate feedback and access sample responses Access additional questions

Track your results and progress Find all this and MORE in jacPLUS 3.2 Quick quiz 3.2 Exercise 3.2 Exercise 1. Outline four ways that traditional explanations of consumer behaviour can differ from those suggested by behavioural economics. (4 marks) 2. Set up and complete a table like that below, relating to types of consumer bias in decision making: (5 marks) Bias or factor Explanation An example UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS (a) Status quo bias (b) Herd behaviour (c) Framing bias (d) Anchoring bias (e) Present bias

3. This question is about herd behaviour: a. When thinking about how consumers make decisions, define what is meant by herd behaviour. (2 marks) b. When consumers decide to buy clothes, explain how their decision, based on the idea of herd behaviour, would differ from one based on a traditional viewpoint. (2 marks) 4. You have been to a lovely presentation with a free supper and convincing spiel by a smooth-talking expert about how to get quick returns of 125 per cent on an investment in Nigeria that he personally recommends. He recounts his successful experiences where he went from rags to riches in just two years. Along with many others that evening, you decide to immediately invest $50,000 in the scheme. According to the behavioural economic theory, explain the ways that this decision differs from the traditional viewpoint of consumer behaviour. (2 marks) 5. a. From behavioural economics, define what is meant by the nudge. b. As a consumer of goods and services, outline two examples of situations where you might experience a nudge. (2 marks) c. As opposed to a disincentive, fine or other punishment, outline one weakness and one strength of using a nudge to influence behaviour related to the problem of leaving litter on the beach. (2 marks) 6. You are an investor and are deciding between two possibilities. One offers a return of 6 per cent a year and the other just 1.2 per cent. By reference to behavioural economics, bounded rationalism, and types of biases, explain why some investors, especially older ones, might settle for the 1.2 per cent option. (3 marks) 7. You are about to flip a coin and you say to your friend, ‘if it’s heads up, I win. You will have to give me $5. Alternatively, if it’s tails up, I agree to give you $5.’ According to behavioural economics, explain why a typical friend might be reluctant to play the game under these rules or conditions. (2 marks) Fully worked solutions and sample responses are available in your digital formats. 3.3 The effectiveness of strategies used by government to influence consumer behaviour KEY KNOWLEDGE • the effectiveness of strategies used by government to influence consumer behaviours Source: VCE Economics Study Design (2023–2027) extracts © VCAA; reproduced by permission. Earlier in our studies we saw that sometimes governments intervene in the economy to help reduce market failure in allocating resources efficiently and improve society’s general wellbeing. Typically, such strategies might include policies such as: • incentives (e.g. the payment of cash subsidies and allowing tax write-offs to reward certain behaviour) • disincentives (e.g. indirect taxes, laws, fines, and government regulations to discourage or punish undesirable behaviour that lower society’s general wellbeing) • educational advertising campaigns (e.g. to improve the knowledge of decision makers, so they are more likely to make rational and beneficial decisions). Government strategies to intervene in the economy UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Incentives Decentives Educational advertising campaigns

All these strategies are designed to modify the way we behave. To be effective in re-allocating resources efficiently, they draw on ideas from the traditional viewpoint of consumer behaviour and more recent studies in behavioural economics. In the next few pages, we will look at some of these government strategies and consider whether they are effective in improving society’s general wellbeing.

3.3.1 The effectiveness of government strategies to reduce alcohol consumption The Australian government attempts to influence consumer behaviour around alcohol using excise taxes, the random breath testing of drivers, and educational advertising campaigns. Let’s start with a look at the excise tax on alcohol. While this tax represents a lucrative source of government revenue in the budget raising over $7 billion a year, the more important goal is to reduce the consumption of alcohol and the incidence of alcohol-related problems (e.g. accidents and property damage, disease, injuries, health, deaths, lower life expectancy, violence, relationships, child abuse, crime, quality of life). The National Drug Research Institute in Australia put the annual cost of these harms at a staggering $67 billion. Our alcohol consumption is too high with 25 per cent of Australians drinking at risky levels, accounting for 25 per cent of all road accidents, 25 per cent of all police time, 30 per cent of family violence, and 15 per cent of hospital emergence presentations. Many studies have shown that the use of excise taxes is a very effective way of reducing alcohol-related harms for individuals, families, and the wider community. They work by simply making alcohol dearer to purchase and hence, following traditional theory, less attractive for consumers. For example, in the case of full-strength beer, the tax represents over 40 per cent of the price of a carton, while whisky and gin are taxed at around 57 per cent. Estimates also suggest that a tax and hence price rise of 10 per cent would reduce alcohol consumption and harm by an average of 5 per cent, especially amongst younger consumers with less income, where demand contracts sharply as the price rises. Thinking of the traditional viewpoint and behavioural economics, the excise tax, combined with informative advertising campaigns (e.g. drink driving, you’re not drinking alone, alcohol and pregnancy — One Drink) and random breath testing of drivers, acknowledge that some consumers have limited willpower to resist excessive alcohol consumption. Not everyone makes well-informed and rational decisions. In addition, the financial penalties of paying the heavy excise tax and, potentially, the fines, possible jail sentences and licence disqualification appeal to the traditional viewpoint of self-interest. Based on the data available, this is what we know about the effectiveness of government strategies in this area: • Information from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) suggests that for one reason or another, average alcohol consumption per capita measured in litres per year has fallen to its lowest level since the late 1960s, especially amongst younger age groups that are more sensitive to higher prices. • Between 2006 and 2020, there was a substantial fall in the proportion of adult consumers regularly consuming alcohol, from around 74 per cent to 66 per cent. • Despite evidence of success, cost–benefit research tells us that government policy could be made more effective. For example, one study claimed that a 75 per cent increase in excise on alcohol would ’maximise UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS the welfare of Australians’ and raise billions of dollars in government revenue that could be used to help reduce the adverse social effects of excess alcohol intake, improving efficiency in resource allocation, and limiting market failure caused by poor consumer decision making.

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable diseases in Australia. It causes a range of cancers (e.g. lung, mouth and throat), heart disease and strokes, stomach ulcers, reduced mobility, and a greatly shortened life expectancy. It also harms the health and wellbeing of passive smokers inhaling second-hand smoke. All up, it kills around 24 000 people each year. Furthermore, it reduces workforce productivity by an estimated $5 billion a year due to increased absences. It is also a burden on our public health system and taxpayers (who need to meet the cost of higher health expenses), it weakens the government’s finances and harms the health of family members. Recently, the National Drug Research Institute (NDRI) estimated that the annual cost to the country was a massive $140 billion. Clearly smoking is a problem and an example of market failure that the government can’t afford to ignore. As a result, several strategies have been tried including laws that require plain packaging (with warnings of the dangers of smoking and graphic images of the impacts on our health). There has also been the Quit advertising campaign (i.e. to educate people, so they make more informed decisions as consumers), age limits for the purchase of tobacco, and the banning of smoking at indoor venues. However, most economists believe that the rise in the rate of excise tax has had the greatest success in significantly reducing tobacco consumption. For example, in 2010, the government increased the excise on tobacco by 25 per cent in one hit, followed every year between 2013 and 2021 by annual rises of 12.5 per cent. These changes made smoking far less attractive and has pushed up the price of a packet of 20 cigarettes to around $40. This has contracted demand for tobacco. As shown in figure 3.1, for one reason or another, there has been a significant reduction in the percentage of Australians who smoke daily (see graph 1), combined with a rise in the proportion who have never smoked at all (see graph 2). The evidence seems to suggest that the government’s strategies have successfully altered consumer behaviour, especially amongst the young. Research also shows that even higher tax rates could further contract consumer demand and improve the health and wellbeing of Australians. However, those who are unable or unwilling to quit smoking face serious opportunity costs and, sadly, their addiction often forces them to cut back on other essentials like food or power. Thinking of the traditional viewpoint and behavioural economics, the advertising campaigns also recognise that consumers are not always well informed, nor do they always make rational decisions. However, the campaigns UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS have helped to change behaviour by making smoking less socially acceptable and push against herd behaviour.

At the same time, the excise tax has been a disincentive. It appeals to the traditional viewpoint that, financially, it would be logical and in consumers’ self-interests to give up smoking.

FIGURE 3.1 Changes in smoking rates amongst the Australian population

70 Graph 1 – Percentage who smoke daily

10 2001

Sex 60 Males Females 50 Persons Per cent 30 40 20 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019 10 0 2001

70 60 50 Per cent 30 40 Sex Males 20 Females Persons 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

Graph 2 – Percentage who have nevered smoked Source: Australian government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, see https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/tobacco-smoking. 3.3.3 The effectiveness of government strategies to influence 0 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS consumers and improve the health system

The Australian government uses a range of strategies to improve the health system. For example, unlike most countries around the world, our Medicare system means that all people can enjoy access to free or heavily subsidised public healthcare. In fact, each year, the federal government spends around $110 billion (around 17 per cent of all budget outlays) on providing healthcare. Clearly this increases the quantity of resources allocated

to this area, helping to reduce market failure and the under-production of a service that we all need. Despite this, there are still reports of long waiting lists in public hospitals and the under-funding of public healthcare for our ageing population.

One important government strategy used to reduce this problem and ease pressures on the public health system is to encourage individuals to take out health insurance, providing access to the private system. As an incentive to join, the government provides Private Health Insurance Tax Rebates of up to 32 per cent of the cost of insurance policies at an annual cost of around $7 billion. This policy seeks to make private health insurance cheaper for consumers, thereby increasing the demand for policies and, supposedly, making more people less dependent on the public system.

Thinking of the traditional viewpoint and behavioural economics, the private health insurance tax rebate is an incentive designed to help overcome consumer self-interest where people are mostly happy to use the public health system paid for by all taxpayers, since this involves no extra cost to them. Possibly, too, it helps redirect some people from herd behaviour of simply relying on the public system to meet their health needs.

Armed with this background information, we now ask the question ‘to what extent have the government’s health strategies been successful in modifying consumer behaviour?’ Let’s start by looking at recent changes in the proportion of the population who have taken out private health insurance. This is shown in figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2 Changes in the proportion of Australia’s population with private health insurance (percentage) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Hospital treatment General treatment Source: Australian government, APRA, Quarterly private health insurance statistics, see https:// www.apra.gov.au/quarterly-private-health-insurance-statistics. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS • Notice that subsidising private health insurance has not managed to increase the proportion of Australians taking out policies. However, it seems that it may have helped to limit the small fall in participation. Part of the problem is that the cost of healthcare is increasing due to our ageing population, new and more expensive treatments, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently, these have put a lot of upward pressure on the cost of premiums while average incomes have been fairly static. So, despite the government’s tax rebate, private health is less affordable and queues in public hospitals have tended to grow even longer.