11 minute read

2.8 How changes in relative prices and profits affect Australia’s resource allocation

that increased the quantity demanded at a given price have shifted the whole demand line horizontally to the right of the original line (from D1 to D2). (5 marks) b. Explain what is meant by an increase in the demand for electricity. (1 mark) c. List and outline three hypothetical non-price microeconomic events or factors that could increase, or have actually increased, the quantity of electricity demanded in Australia at all possible prices from

D1 to D2. (3 marks) d. Quoting figures from your diagram, explain what happened to the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity of electricity in this market following the increase in demand from D1 to D2. (2 marks) e. Referring to relevant parts of your diagram, clearly describe the main steps whereby there was a move in equilibrium from E1 to E2. For instance, why did the equilibrium price of electricity change from

Advertisement

P1 to P2? (4 marks)

Examine table 2.6 containing hypothetical data showing both the original quantities of electricity demanded and supplied at various prices in the market, with another set of data showing the effects of new and weaker non-price conditions that decrease the quantity supplied at any given price.

TABLE 2.6 The original quantities of electricity demanded and supplied, plus the new decreased quantity supplied, at any given price in the market

Possible price per kWh Original quantity of electricity demanded per day (millions of kWh) at a given price (D1) Original quantity of electricity supplied per day (millions of kWh) at a given price (S1)

6. New decreased quantity of electricity supplied per day (millions of kWh) at a given price (S0) $0.10 35 0 $0.15 30 10 5 $0.20 25 15 10 $0.25 20 20 15 $0.30 15 25 20 $0.35 10 30 25 $0.40 5 35 30 f. Using table 2.6, accurately construct and fully label a combined D–S graph showing the original demand (D1) and the original supply (S1) curves or lines for the electricity market, along with the original market equilibrium (E1). Your labelling must include an appropriate scale and units for each of the two axes (with both scales rising by regular intervals from zero), along with D1, S1, E1, P1 and Q1. On the same graph, plot and label a second supply curve or line (called S0) to show the effects of a reduced supply of electricity on the new equilibrium price (called P0) and equilibrium quantity (called Q0). Notice how the new non-price supply conditions that decreased the quantity supplied at a given price have shifted the whole supply line to the left of the original line (from S1 to S0). (5 marks) g. Explain what is meant by decrease in the supply of electricity. (1 mark) h. List and outline two hypothetical non-price microeconomic events or factors that could decrease, or have actually decreased, the quantity of electricity supplied in Australia at all possible prices from S1 to S0. (2 marks) i. Quoting figures from your diagram, explain what happened to the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity of electricity in this market following the decrease in supply from S1 to S0. (2 marks) j. Referring to relevant parts of your diagram, clearly describe the main steps whereby there was a move in equilibrium from E1 to E0. For instance, why did the equilibrium price of electricity change from P1 to P0? (4 marks) Non-price conditions or factors can affect the quantity of a particular good or service demanded or supplied at a given price. a. For each of the following markets, list the two most important non-price factors or conditions that could change the quantity demanded at any given price, shifting the position of the demand line and therefore 5 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS causing either a rise or fall in the market equilibrium price: (20 marks)

Market Non-price factors or conditions that change the quantity demanded at a given price, horizontally shifting the whole demand line

i. Property

ii. Hospitals

iii. Surfboards iv. Wool v. Travel vi. Labour vii. Electricity viii. Butter ix. Milk x. Smartphones b. For each of the following markets, list the two most likely non-price factors or conditions that could change the quantity supplied at any given price, shifting the position of the supply line and therefore causing either a rise or fall in the market equilibrium price: (16 marks)

Market

Non-price factors or conditions that change the quantity supplied at a given price, horizontally shifting the whole supply line i. Canola ii. Doctors iii. Iron ore iv. Bananas v. Workers vi. Cars vii. Houses viii. Televisions UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

7. The quantity of a particular good or service demanded at a given price is affected by changing prices in the market for a substitute product or in the market for a complementary good or service. In other words, markets for substitutes or those for complements are linked to that of the original product or service. a. Explain what is meant by a substitute product. (1 mark) b. Explain what is meant by a complementary good or service. (1 mark) 8. For each pair of markets shown in table 2.7: a. Indicate whether the two products are substitutes or complements. b. Complete each small demand diagram to show the effect of a new non-price factor on the original demand line for a substitute or a complement. (10 marks) TABLE 2.7 The impact on the quantity demanded at a given price of events affecting substitutes and complements

a. Substitutes or complements? b. Effect on the demand for the substitute or complement

i. Butter and margarine are called ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Effect of a rise in the price of butter on the demand for margarine: Price/unit D1 Quantity ii. Coffee and sugar are called ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Effect of a rise in the price of coffee on the demand for sugar: Price/unit P D1 Quantity iii. Petrol and cars are called ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Effect of a fall in the price of petrol on the demand for cars: Price/unit P D1 Quantity iv. Beef and chicken are called ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Effect of a fall in the price of chicken on the demand for beef: Price/unit P D1 Quantity

P UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

v. Coal-fired and solar power are called ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Effect of a government subsidy for households installing solar panels on the price of coal-fired electricity:

Price/unit P

D1 Quantity 9. Download the D–S diagrams as a digital document from the Resources tab and use this to complete the question. Complete and fully label the D–S diagrams in figure 2.17, each representing a single competitive market, to show the hypothetical effects of an event that alters the non-price conditions of demand and/or conditions of supply, thereby changing the equilibrium price and quantity. In most cases, you will need to add a second D line (D2) or a second S line (S2), along with a new equilibrium price (P2) and quantity (Q2). (18 marks)

FIGURE 2.17 The impact of new non-price factors in single markets on demand–supply diagrams The effect on the market for raspberries of the ending of the growing season The effect on the market for coal of a slowdown in global economic growth The effect on the market for plastic swimming pools of a heatwave The effect on the market for caged eggs of a successful advertising campaign by the RSPCA The effect on the market for synthetic fibres (like polyester used in clothing) of a fall in oil prices The effect on the market for hotel rooms here and overseas of a rise in consumer confidence The effect on the market for alcohol of an increase in the government excise tax on sellers The effect on the market for health care of a rise in the birth rate

The effect on the market for solar panels of an increase in the government subsidy paid to sellers UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS

Fully worked solutions and sample responses are available in your digital formats.

Resourceseses

Digital document D–S diagrams

2.8 How changes in relative prices and profits affect

Australia’s resource allocation

KEY KNOWLEDGE • the role of the market mechanism and relative prices in the allocation of resources in a market-based economy

Source: VCE Economics Study Design (2023–2027) extracts © VCAA; reproduced by permission. In this section we continue our examination of the operation of the market mechanism or price system by again making the connection between a change in the relative price of one good or service against another, and how this affects the economic decisions involving how Australia allocates its scarce resources between alternative uses. You may recall that all economies face the basic economic problem of relative scarcity. Because not all wants can be satisfied, we must make choices and answer three important economic questions: • What type and quantity of goods and services should be produced? • How should these goods and services be produced? • For whom should these goods and services be produced? As we previously pointed out, in Australia’s predominantly market-based economy, profitseeking owners of resources rely mainly on the operation of the price system to guide their decisions and allocate resources between various types of goods and services. Here,

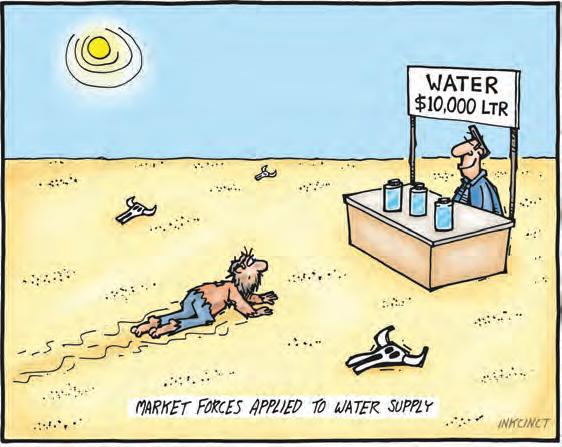

FIGURE 2.18 Market forces involve the operation of demand by buyers and supply by sellers. Together, these forces determine the relative market price as an indicator of the relative scarcity of each good or service, such as bananas or bottled water. In a competitive market, strong demand and/or limited supply would cause the product to be scarcer and this would be reflected in a higher price in the market. market forces involving demand and supply operate to determine the relative price, at equilibrium, of one good or service against another. Over a period of time, the relative prices of each good or service change due to new non-price conditions affecting the level of demand and/or level of supply. In turn, changes in relative prices cause price signals that act as incentives for decision makers. These affect the relative profitability of each area of production, thereby influencing the way the three basic economic questions are answered. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2.8.1 How the price system answers the ‘what and how much to produce’ question

• A relatively higher market price

Imagine that the equilibrium market price of ice-cream increased relative to that for yoghurt due to an increase in consumer demand for ice-cream at all possible prices (perhaps reflecting the operation of non-price factors like successful advertising, population growth or a rise in disposable income) while the demand for yoghurt fell (perhaps due to a non-price condition like a health scare). Here, it is quite likely that ice-cream would become relatively more profitable than yoghurt (assuming no other changes occurred). Higher profits in ice-cream would act as a positive incentive, attracting extra resources into this area of production, perhaps pulling resources out of yoghurt. • A relatively lower market price Alternatively, what would happen if the equilibrium market price of ice-cream fell, perhaps because there was an increase in the supply of ice-cream at all possible prices (perhaps due to lower costs such as milk or transport) relative to its demand? In this case, it is likely that ice-cream producers would face relatively lower profits against those for yoghurt. This disincentive would tend to repel resources from ice-cream production while encouraging more to move into yoghurt. In deciding what to produce — whether it be ice-cream or yoghurt, rice or wheat, cars or computers, wool or coal, or childcare or education — the market can usually provide the price signals, incentives or information to help owners of resources make the right production decisions that give consumers the types of goods and services they most want. One weakness, or market failure of this system, is that there are situations where socially undesirable yet profitable goods and services (e.g. illegal drugs, pollution, guns and prostitution) may be overproduced, while low priced, unprofitable or socially desirable goods and services (e.g. affordable healthcare, education and housing) are under-produced. In these instances of market failure, there is a strong case for government intervention in or regulation of some markets using taxes to discourage, or government subsidies to encourage, some types of production. This can alter the allocation of resources. 2.8.2 How the price system answers the ‘how to produce’ question In order to maximise profits, private owners of resources usually seek to minimise their production costs and maximise efficiency. So, for example, if it is cheaper to produce a pair of jeans using mostly labour resources rather than capital equipment like laser-operated machines, then this would normally be the preferred method of manufacture. Again, the market-based system involving demand and supply would provide the necessary price information as to which production method is the cheapest to use. One possible reason why labour might be cheaper in this case could be that its supply is high relative to demand. This would cause wage costs (the market price of labour) to be relatively lower (against the cost or market price of machinery). However, sometimes the cheap production methods used by firms could risk the wellbeing, health and safety of workers and the general community. For instance, some firms may want to cut their costs by having dangerous working conditions or releasing pollution, because these methods are relatively cheaper. Again, there may be a justification for having some government regulation of production methods (e.g. occupational health and safety standards) in cases where the market fails to make good decisions. UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2.8.3 How the price system answers the ‘for whom to produce’ question