The Final Issue

WHAT THE DECLINE OF AIDS ORGANIZATIONS TELLS US

THE TRUE STORY OF BRANDON TEENA

PLUS: RUSSELL TOVEY, KAWIKA GUILLERMO, DREW DROEGE, MARC BENDAVID, ERIC MCCORMACK AND REVRY’S CO-FOUNDERS TALK TO IN

WHAT THE DECLINE OF AIDS ORGANIZATIONS TELLS US

THE TRUE STORY OF BRANDON TEENA

PLUS: RUSSELL TOVEY, KAWIKA GUILLERMO, DREW DROEGE, MARC BENDAVID, ERIC MCCORMACK AND REVRY’S CO-FOUNDERS TALK TO IN

PUBLISHER

Patricia Nicolas

EDITOR

Christopher Turner

ART DIRECTOR

Georges Sarkis

COPY EDITOR

Ruth Hanley

SENIOR COLUMNISTS

Paul Gallant, Doug Wallace

CONTRIBUTORS

Jesse Boland, Matthew Creith, Adriana Ermter, Shane Gallagher, William Koné, Karen Kwan, Elio Iannacci, Stephan Petar

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT

Charlie Smith

COMMUNITY RESOURCE NAVIGATOR

Tyra Blizzard

ADVERTISING & OTHER INQUIRIES (416) 800-4449 ext 100 benjamin@elevatemediagroup.co

EDITORIAL INQUIRIES (416) 800-4449 ext 201 editor@inmagazine.ca

IN Magazine is published six times per year by Elevate Media Group (https://elevatemediagroup.co). All rights reserved. Visit www.inmagazine.ca daily for 2SLGBTQI+ content.

180 John St, Suite #509, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1X5

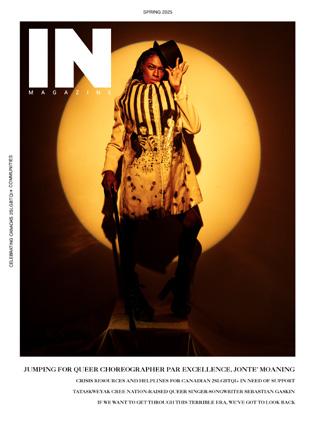

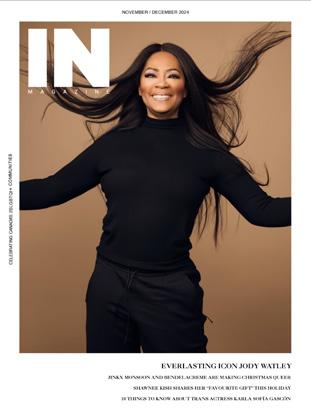

ON THE COVER:

06 | WHAT THE DECLINE OF AIDS ORGANIZATIONS TELLS US ABOUT MOVING PAST OUR TRAUMAS – AND OUR SUCCESSES

The end of Canada’s oldest HIV service agency should be a cue for today’s 2SLGBTQI+ activists to start again, this time hopefully from a place of less fear and ignorance

08 | GET LIT

Choosing Canadian-made candles goes beyond setting a festive mood this season

11 | CLOSING THE GAPS

Winnipeg’s CIN and Nine Circles Community Health Centre are reimagining care, and turning advocacy into action

13 | THE PROTEIN CRAZE

How much of this macro do we really need?

14 | KAWIKA GUILLERMO ON QUEERNESS, GAMES, AND FINDING SELF IN DIGITAL WORLDS

The author of Of Floating Isles talks to IN about turning games into stories of queerness, breaking stereotypes, and survival

16 | MARC BENDAVID EXPLORES THE POWER OF MEMORY AND TRANSFORMATIVE BONDS

In his debut novel The Sapling, the Canadian actor beautifully shares the profound, lifealtering friendship he formed with his teacher

18 | LOOKING INSIDE THE QUIET DISCRIMINATION OF “LOOKISM”

There’s a certain kind of prejudice in this world, and it isn’t pretty…

20 | DINNER WITH FRIENDS AND THE GROWING PAINS OF ADULTHOOD

The feature film debut of CSA winner Sasha Leigh Henry not only challenges the conventions of the “hangout” story, but sheds light on a Black queer narrative rarely seen in Canada

23 | RUSSELL TOVEY HOPES FLIRTING ISN’T OVER

IN Magazine talked with the Looking actor to discuss what drew him to play a closeted American man in Plainclothes, plus the danger of public sexual interactions, and the loss of queer signalling during the Grindr age

26 | THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING MESSY

A conversation with actor/writer Drew Droege about his newest play, which takes a stab at unhinged white gays on the loose

30 | REVRY’S CO-FOUNDERS REFLECT ON A DECADE OF BRINGING QUEER JOY TO THE WORLD

Co-founders Damian Pelliccione and Christopher J. Rodriguez chat about the streaming network’s early days, the success of King of Drag and what viewers can expect in the future

32 | STEAMY SAUNA

Queer love heats up in this foreign drama, an intimate reimagining of Romeo and Juliet

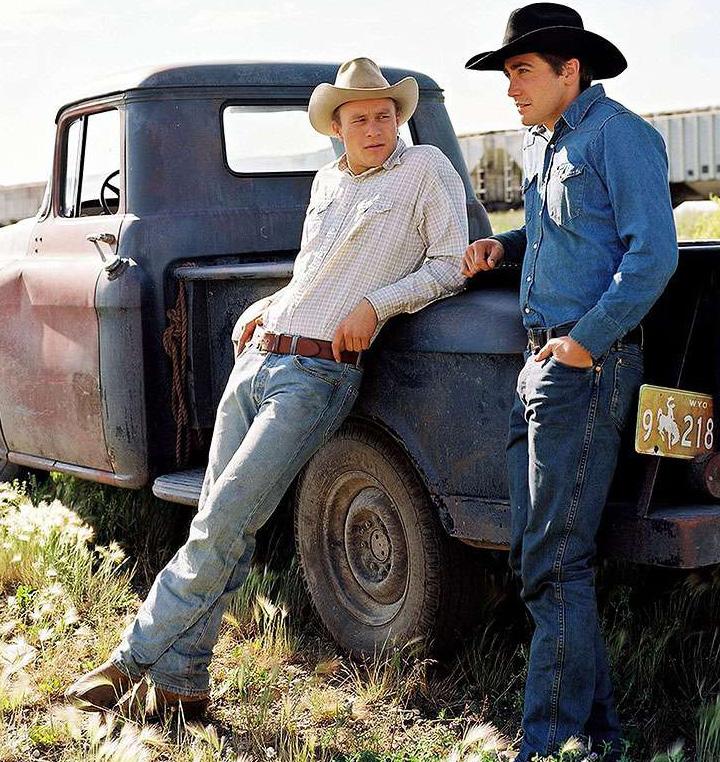

34 | 20 YEARS LATER AND BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN IS STILL IMPACTFUL

Brokeback Mountain premiered in 2005 during a very different era for gay rights, but its legacy lives on through its indelible characters

38 | ERIC MCCORMACK HEADS BACK TO SCHOOL IN MIDDLEBRIDGE MYSTERIES

The Canadian actor talks about joining the new Audible Original podcast, while reminiscing on the legacy of Will & Grace

40 | HOW BRANDON TEENA’S MURDER CHANGED HOW WE TALK ABOUT GENDER AND JUSTICE

His 1993 murder exposed the dangers of living authentically in a world not ready to understand. Three decades later, Teena’s story continues to shape how North America talks about gender, justice, and who deserves protection

46 | SNOW GLOBAL

From mountain hut revelry to drag queens on skis, Arosa Gay Ski Week in southeastern Switzerland proves that the Alps have never looked this fabulous

50 | FLASHBACK: DECEMBER 25, 1977 IN 2SLGBTQI+ HISTORY

Beverly LaSalle is murdered on All In The Family

The end of ACT, Canada’s oldest HIV service agency, and other AIDS organizations, should be a cue for today’s 2SLGBTQI+ activists to start again, this time hopefully from a place of less fear and ignorance

By Paul Gallant

In this season of the hilarious FX TV comedy The English Teacher, the titular gay English teacher is quietly delighted when his high schoolers decide they want to perform Angels in America , Larry Kramer’s epic two-part play about, among other things, the HIV/ AIDS crisis in the 1980s. But then Mr. Marquez, played by out show creator Brian Jordan Alvarez, is thrown for a loop when his students want to adapt the landmark work into a performance about their own experiences of COVID-19.

“I mean, this stuff all happened, like, 90 years ago,” declares one student.

“Why didn’t the gay guys just stop having sex? Wouldn’t that have solved the problem?” asks another.

“That’s not possible for those people, no offence, queen,” replies the first student, looking knowingly at Mr. Marquez.

“You have to understand,” the teacher tells his class. “They didn’t know what AIDS was. They didn’t know where it came from. There was so much fear and so much misinformation.”

“Like with COVID?” says the student who gets the last word.

Since the summer of 1981, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. reported a rare pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma in five young gay men in Los Angeles, the fear of HIV/AIDS – or the denial of that fear – has been intrinsically connected to the lives of gay and bi men. First, it was a mystery disease. Then it was a disease caused by sex, especially gay sex. Fear of AIDS became as much a part of being gay as coming out. My own coming out in the 1990s was paired with buying a large box of condoms, and having my GP tell me I needed to get myself into a monogamous relationship ASAP. That’s what gay life was: being casual and sometimes greedy about who we have sex with. But also being diligent in how that sex unfolded. The management of bodily fluids was a matter of life and death.

“If only we live to see the day when homophobia, transphobia, racism and poverty no longer require vigilance and attention – now that will be a peace dividend.”

AIDS was a societal crisis, an emotional crisis and a spiritual crisis as much as it was a health crisis. And it struck the gay community just as we were asserting ourselves on the wider social and political stage, particularly in North America and Europe. More people were coming out, more bars and saunas and other gay-oriented businesses were opening, more mainstream entertainment was referencing gay life, more politicians were acknowledging 2SLGBTQI+ people. It should have been pure euphoria. But it wasn’t, because there were also, at the same time, more funerals for men who were dying very young. The most vivid memories for many gay men who are over 50 today was of friends’ unexpectedly quick, painful deaths.

Prevention strategies improved: first, the wider use of condoms, then PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) in the form of daily prevention pills and now injections. Treatments improved dramatically after a decade of being as toxic as the virus itself.

But that first decade of HIV/AIDS inflicted a wound on our psyches, our sense of ourselves, of what it meant to be a good gay. For the religiously inclined, there was a sense that AIDS was a punishment for the sin of homosexuality. I knew gay guys who, right up until the 2010s, believed they were probably HIV-positive but avoided getting tested, and therefore avoided treatment, because they could not come to terms with the weight of being HIV-positive. Though highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) came onto the market in 1996, allowing HIV-positive people to live long and healthy lives with fewer side effects, and PrEP started being prescribed in 2012, the story that a certain generation of gay and bi men told ourselves about HIV/AIDS did not change very much. In the early years of the epidemic, we were neglected and ignored. Sometimes anger seemed like the only way to get results.

Forty-four years later, our institutions are finally feeling the pressure to reframe the issue, to let the facts of HAART and PrEP, rather than our collective trauma, inform decisions. Next spring, Canada’s oldest HIV service organization will close after 42 years of leading the charge against the disease. The AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) is not the only HIV/AIDS organization that is acknowledging the new world we live in, a world that seems to be shifting away from progressive thinking and empathy. In the U.K., NAM aidsmap, a long-running HIV information charity, closed up shop in 2024, transferring its assets to the Terrence Higgins Trust and National AIDS Trust. AIDS Fund Philadelphia shut down in 2024, while the San Francisco AIDS Foundation went through a dramatic downsizing in June 2025.

This is mostly good news. When a societal problem is mitigated or solved, there is no sense in directing community resources towards it. If only we live to see the day when homophobia, transphobia, racism and poverty no longer require vigilance and attention – now that will be a peace dividend. Organizations other than ACT are still doing good work. But few victories are clear-cut. The AIDS “solution” has primarily been a pharmaceutical one, one delivered by corporate entities beholden to shareholders. Reduced HIV infection rates, and healthy lives for those who are positive, are in the hands of big business, government funders and regulators…not the most dependable friends.

Though grassroots campaigns to get gay and bi men to use condoms were perhaps less effective in the long term than pills and injections, there’s a loss of a sense of community, a loss of empowerment in handing over our health to big pharma. Our well-being has been commodified. Our community’s crisis has become one of a thousand demands on the healthcare system. Even for the gay community, monkeypox and drug-resistant syphilis have become tougher nuts to crack. ACT was founded in 1983 by a group of concerned community members, all volunteers and activists. Toronto’s Hassle Free Clinic, founded in 1973, also had humble grassroots origins. But they’ve been overshadowed by the slick efficiency of the self-check-in terminals at Toronto’s HQ, a hub for “cis guys into guys and two-spirit, transgender and non-binary people.” Funded by the provincial government as well as by donations from companies like Gilead Sciences, which makes the HIV treatment drug Biktarvy and the HIV prevention drug Descovy, HQ is a remarkable service. But it has less heart than its predecessors.

It’s hard to find a way forward after an emotional and monumental event. There’s an urge to fight the last war again and again. That’s true not only for HIV/AIDS and other horrors. Our community’s cockiness about the successful campaign for equal marriage, which was legalized nationally 20 years ago, has probably made us less effective in fighting the current backlash against our community, particularly in defending trans rights. Today’s issues are more about attitudes, health spending and educational policy than the legal rights we advocated for during the marriage debate. Organizations that were built to win court cases haven’t shown themselves to be great at other forms of advocacy.

The AIDS crisis did teach us something: how to start from scratch, from a place of fear and ignorance, to build something that saves lives and maybe changes the world. The end of ACT and other AIDS organizations should be a cue for today’s 2SLGBTQI+ activists to start again, this time hopefully from a place of less fear and ignorance.

Choosing Canadian-made candles goes beyond setting a festive mood this season – they are a thoughtful way to celebrate craftsmanship, support local industries and bring home scents that tell a uniquely Canadian story

By Adriana Ermter

As the days shorten and winter wraps itself around us, candles become more than decoration – they become a ritual. A flickering flame can soften the edges of a cold night, turn an ordinary room into a warm refuge and anchor us during the busiest season of the year. On the cusp of the holidays, candles are everywhere: glowing on dinner tables, nestled into gift boxes and filling homes with cozy, heart-warming scents like pine needles, spices and wood fires. This year, however, what we choose to light matters.

“There’s a whole movement for keeping the dollars close to home right now,” explains Michelle Kalman, founder of The Go-To, a public relations company focused on representing Canadians and their brands. “Canadians want to back Canadian brands, financially and personally.”

Sure, a candle may seem like, well, just a candle. But buying Canadianmade reshapes how we support local craftsmanship, entrepreneurship

and economic sustainability. Every purchase helps fuel local farms, sustains beekeepers, supports essential oil producers, strengthens small businesses and protects the ecosystems that make these candles possible.

“It’s important for people to support the brands that are helping support the economy in which they live,” says Victoria Mierzwa, the cofounder of LOHN Candles, based in Toronto. “It benefits everyone: manufacturers, wholesalers, the employees of wholesalers, the suppliers of raw materials.… Buying a candle from one brand doesn’t just benefit that brand: it benefits everyone that’s connected to that brand, and that can make a huge impact in supporting all types of businesses.”

Which makes the choice to shop Canadian-made more relevant than ever. A 2025 study from Food Processing Skills Canada (FPSC) found that 81 per cent of Canadians are motivated to buy Canadian. While ongoing U.S. tariffs may have ignited this shift, the outcome is

undeniably positive: it supports communities, protects the environment and celebrates locally grown ingredients.

A well-lit advantage

“Homegrown candles are very high-touch products,” affirms Mierzwa. “You know you’re going to get a small batch candle that is handmade, and the quality is impeccable. There’s no automation. It’s all about the hand mixing of the wax and the fragrance, the hand pouring and packaging by hand. It’s about keeping the business within Canada and supporting the Canadian industry.”

This industry blends the agriculture and scents of our landscape – soy fields in Ontario, cedar groves in British Columbia, golden beeswax from Prairie hives and more. Each ingredient tells a story tied to the land and the people who cultivate it.

Homegrown ingredients

Start with soy wax. Canada’s soybean fields stretch across Ontario, Quebec and the Prairies. According to Statistics Canada, 1.6 million acres of soybeans were planted in Manitoba alone this year. With nearly 200,000 working farms across the country, buying soy-based candles supports Canadian farmers and reinforces the shift towards renewable, plant-based resources.

When harvested and pressed, those soybeans produce a clean, creamy wax that burns slowly and evenly. The wax has a smooth, buttery texture and a subtle, natural scent that doesn’t compete with fragrance oils. Brands like SOJA&CO in Montreal, and Homecoming Candles and the Canvas Candle Company in British Columbia, rely on 100 per cent hand-poured soy wax, creating candles that last longer and emit fewer toxins than paraffin alternatives.

“A 2025 study from Food Processing Skills Canada (FPSC) found that 81 per cent of Canadians are motivated to buy Canadian.”

While not plant-based, beeswax is another Canadian treasure. Sourced from hives scattered across British Columbia and Alberta, it is golden, warm and rich with a natural honeyed aroma. It burns cleanly, releasing negative ions that help purify the air. BC Candles in Richmond, B.C., is one of many companies harnessing this ingredient’s purity. And beekeeping is on the rise. Statistics Canada notes nearly 15,500 of these buzzy professionals in 2024, marking six years of steady growth. Supporting beeswax production sustains both the candle industry and the pollinators vital to Canada’s ecosystem and food supply.

Coconut wax, while not locally grown, plays a starring role when blended with soy for a smooth, clean burn. Canadian brands like Hollow Tree Candle Co. in the Pacific Northwest source ethically produced coconut wax and blend it locally. What makes their candles distinctly Canadian is how this wax becomes a vessel for homegrown

scent stories – forest floors after rain, cedar cabins, mountain air – all transformed by Canadian craftsmanship.

And then there are the essential oils. Canadian forests and fields provide an abundance of aromatic botanicals, from spruce, pine, cedar and fir, to lavender, peppermint and clary sage. These oils are extracted from leaves, needles and flowers, capturing the pure essence of nature. Vancouver-based Woodlot builds its plant-based aromatherapy blends around these materials, creating scents so evocative that opening the packaging to one of their candles feels like stepping into a West Coast forest and taking a deep breath of crisp air, damp earth and resinous woods. Supporting brands like Woodlot means supporting the growers, distillers and harvesters who make these ingredients possible.

The impact of choosing Canadian candles reaches far beyond the checkout counter. Economically, it keeps dollars circulating nationwide among farmers, beekeepers, essential oil producers, artisans and retailers. Ethically and culturally, it strengthens identity and pride.

“When you live in Ontario, buying a candle that was made in Newmarket, like one from The Market Candle Company, just feels authentic,” says Kalman. “It makes you feel good, too, because you know it supports the local maker. It’s like a rebellion against generic buying. It’s Canada strong – a way to check that box to promote and remind ourselves to be Canada proud.”

That pride is often rooted in a sense of place – moments like camping in Tofino or summers in Muskoka. Many Canadian brands weave these inspirations into their scents. B.C.’s Homecoming, for example, is known for its clean, modern fragrances that echo West Coast sea air and towering evergreens. LOHN crafts poetic scent narratives inspired by journeys and rituals, transporting you to windswept lakeshores, snowy trails and sunlit kitchens.

“We like to create scents with our candles that feel a little more personal, like our fir and cypress tree scent ‘Evergreen,’ a juicy red wine ‘Bordeaux,’ and a wild ivy called ‘Snowdrop’ that’s super, super magical,” enthuses Mierzwa.

Scents and sensibility

For consumers, candles offer hyper personalization – a way to align purchases with values while supporting Canadian artisans and sustainability. Mala, based in Vancouver, plants a tree for every candle sold, and recently partnered with Veritree to verify their reforestation impact. Vigyl Candles blends light with art through gender-fluid, photography-like inspired packaging, creating a shared cultural experience. Wild Flicker in Hanover, Ont., which began as a side hustle and a counter to migraine-inducing scents, has evolved into a thriving vegan, clean-burning brand.

After all, says Mierzwa, candles are “the first and the last piece of the puzzle. You’ve come home, you’ve maybe unloaded your groceries, you’ve taken off your shoes, you’re ready to enjoy your space. The ritual of lighting a candle signifies something’s about to happen. Maybe you’re entertaining or maybe you’re going to relax.”

Either way, when you light a Canadian candle, it’s always a small act with a big impact.

Inside the fight for equity — and how Winnipeg’s CIN and Nine Circles Community Health Centre are turning advocacy into action

Across Manitoba, the numbers tell a story that demands attention. HIV incidence rates in the province are now more than three times higher than the national average, making Manitoba a focal point in Canada’s ongoing HIV response. It’s a situation shaped not only by viral transmission, but by systemic inequities – and by the persistence of social, economic and racial barriers that have allowed a public-health crisis to deepen quietly in plain sight.

Behind the statistics are communities facing overlapping challenges: poverty, stigma, substance use, and the lingering legacy of colonialism that continues to affect Indigenous health outcomes. While the rest of Canada has seen gradual progress, Manitoba’s rates are rising. That reality has become a rallying cry for a network of advocates determined to change the narrative.

A province confronting inequity

While sexual contact remains the leading cause of HIV transmission across Canada, Manitoba’s epidemic looks markedly different. Here, injection drug use is the primary driver: a reflection of how inequitable access to health care, harm-reduction tools, and prevention education has left certain communities disproportionately vulnerable.

According to Mike Payne, Executive Director of Nine Circles Community Health Centre and co-strategic facilitator for the CIN (Collective Impact Network), health disparities are the true engine behind the province’s growing HIV rates. Factors such as a lack of awareness of HIV risk, limited access to PrEP and PEP, structural racism, and stigma have all contributed to the alarming rise in new diagnoses.

Payne notes that HIV is significantly impacting First Nations and Indigenous people and communities in Manitoba – an outcome that Nine Circles believes is a direct result of long-standing structural racism.

“Nine Circles and its broad community partners have established a clear provincial HIV strategy,” Payne tells IN Magazine, “and our advocacy efforts push our community, regional, provincial and federal leadership to acknowledge, co-lead and accept shared accountability with the community to raise awareness of HIV and opportunities for prevention, to reduce stigma around HIV, sexual health, substance use, mental health and homelessness, and to take direct action to address the underlying causes.”

Building a network for change

Amid these challenges, the CIN has emerged as one of Manitoba’s most forward-thinking advocacy coalitions. Co-led by people with lived experience and guided by collaboration among service providers, researchers and health-system leaders, the network aims to bridge the gaps between policy, practice and lived reality.

“We have been at the forefront of bringing new community-led research and innovation,” says Payne. “Our advocacy struggle is gaining regional, provincial and federal commitments to sustain innovations beyond the pilot or research stage. We work to evolve new ways of working together for collective impact.”

The CIN was born from a recognition that Manitoba needed a more coordinated strategy: one that treated HIV not just as a medical issue, but as a social and structural challenge requiring partnership at every level. Through advocacy, consultation and research, the network has been pushing for long-term solutions rather than temporary or project-based fixes.

Payne emphasizes that there are unique challenges in different communities across Manitoba, and distinct solutions to those challenges are required at the regional and community levels – solutions that take time, skill and resources to build.

From advocacy to action: The example of Nine Circles

At the centre of the CIN’s work stand community organizations like Nine Circles Community Health Centre, a Winnipeg institution that exemplifies what the Network is striving for province-wide. It integrates clinical

services, harm reduction, education and social support into a seamless model that treats health not as a transaction, but as a relationship.

“Nine Circles envisions a future where all Manitobans who live with, or are vulnerable to, HIV and other STBBIs [sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections], receive equitable health and social services that fully meet their needs,” says Payne.

The centre’s philosophy is grounded in compassion and non-judgmental care. Its clinicians work in partnership with clients, addressing the social conditions that make treatment adherence difficult – whether that’s unstable housing, food insecurity or trauma.

Harm reduction as health justice

Nowhere is Nine Circles’ impact more visible than in its Pit Stop program, which offers safer drug-use and safer-sex supplies, take-home naloxone kits, a needle exchange and drug-checking services. The goal isn’t just to prevent HIV infection resulting from shared needles or overdose; it’s to affirm that every person deserves dignity and safety, regardless of circumstance.

But the work doesn’t stop at direct services. Nine Circles also acts as a hub for education and community connection, offering workshops, peersupport spaces and opportunities for leadership development. Through these efforts, people with lived experience are empowered not only as clients, but as advocates and educators.

The road ahead

The path forward will require continued advocacy, collaboration and sustained funding. While Manitoba’s community sector has been innovative, it cannot sustain progress without stable policy support and investment. Advocates are calling for an integrated provincial HIV strategy that unites health regions, Indigenous leadership, and community organizations under a shared framework of accountability. That framework would prioritize harm reduction, prevention, testing access and culturally appropriate care – but just as importantly, it would prioritize people with lived experience as equal partners.

Across Manitoba, organizations like Nine Circles and networks like CIN are demonstrating that community-led innovation can lead the way. What they need now is consistent commitment from decision makers to maintain the momentum.

A blueprint for change

As the landscape of HIV care evolves, Manitoba offers a powerful case study in what’s possible when communities lead with compassion and courage. The CIN’s collaborative advocacy is reframing what public health can look like – less about bureaucracy and more about partnership. And at the heart of it all, Nine Circles Community Health Centre remains a living testament to those ideals. It’s where the policy meets the person, where advocacy becomes action, and where care extends far beyond the clinic walls.

For the thousands of Manitobans living with or at risk of HIV, that kind of holistic, inclusive and justice-driven care isn’t just life-changing –it’s lifesaving.

For more information on Manitoba HIV/STBBI Collective Impact Network, visit www.cinetwork.ca. For more information on Winnipeg’s Nine Circles Community Health Centre, visit www. ninecircles.ca. For more information on the Manitoba HIV Program, visit www.mbhiv.ca.

ViiV Healthcare Canada supports the HIV/AIDS community through various initiatives across the country, including the evolving needs of Nine Circles. To learn more about ViiV Healthcare Canada, visit www.viivhealthcare.ca.

This content is sponsored by ViiV Healthcare Canada.

How much of this macro do we really need?

By Karen Kwan

Everyone seems to be obsessed with getting more protein into their diet: from adding cottage cheese in every type of recipe to foods pumped up with the macro (everything in the grocery store – from ice cream to candy – is loaded with more protein these days). But is this just a fad? And is there a maximum to how much protein you should be consuming?

This macronutrient has gotten a ton of attention in the past few years, thanks to its association with building muscle and losing weight (compared to fat and carbs, both of which people associate with being at the root of weight gain). Protein is key to our health, as it’s the only macro that contains nitrogen (which the human body does not produce). The amino-acid proteins we get from the foods we eat benefit not only our muscles, but also our bones, hair, nails and immune systems.

How much protein do we actually need?

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body mass. So, for example, if you’re 140 lbs. (63.5 kg), you need a minimum of 51 grams of protein daily. Your needs may be different, though, depending on your age, physical activity level and weight. For example, if you’re 40 years or older (which is when we start to lose muscle mass as we age), you should aim for 1-1.2 g per kilogram of body mass. If you exercise regularly, you have greater protein needs as well. If you’re an adult who works out regularly, you’ll want to try to get 1.1-1.5 g per kilogram of protein daily (70 g if you weigh 140 lbs.). And finally, if you’re overweight, a doctor or dietitian can best help you assess what your protein needs are.

The irony about today’s protein craze is that while many of us are scrambling to get more protein into our diets, many experts say North Americans meet or even exceed our protein needs; according

to 2015 data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the average person in the U.S. and Canada gets a full 90 g a day.

Once you’ve calculated how much protein you actually need, you might be wondering how to best approach getting that protein. If you’re not already getting your RDA of protein, experts recommend you take small steps and add a little more protein to your meals and snacks throughout the day, rather than primarily adding it all into your breakfast, for example.

Also, you don’t have to resign yourself to having protein shakes all the time (although if you’re busy, a protein shake is a convenient way to hit your protein target). Ultimately, you should aim to get your protein from a variety of sources so that you’re consuming micronutrients from a variety of whole foods rather than a steady diet of protein shakes.

The body can’t store protein – so if you consume protein beyond what your body needs, it just gets used as energy or stored as fat; it doesn’t, as many may hope, translate into developing more lean muscle (you need to do additional strength training to help you build muscle). Getting too much of this macro hasn’t been shown to poorly impact health, though. That said, there have been some findings that people with kidney disease might be putting excess stress on their already compromised kidneys with a protein-heavy diet. As well, studies have shown that, given that many highprotein foods are also high in total and saturated fat, consuming too much protein over an extended period of time may lead to elevated blood lipids and heart disease. It’s always best to speak to your doctor about your dietary needs if you have pre-existing conditions and have any concerns about your protein intake.

The author of Of Floating Isles talks to IN about turning games into stories of queerness, breaking stereotypes, and survival

Vancouver’s Kawika Guillermo isn’t just a gaming expert; he’s an established author with a pretty notable career. His debut novel, Stamped: an anti-travel novel, won the 2020 Association for Asian American Studies Book Award for Creative Prose, and his second novel, All Flowers Bloom, won the 2021 Reviewers Choice Gold Award for Best General Fiction/Novel. His latest release, Of Floating Isles, is a collection of essays that use video games as a creative way to explore deeper themes of identity, belonging and community, especially for marginalized individuals.

In Of Floating Isles , the award-winning author and professor explores how video games served as both a compass and a mirror throughout his life. As a games scholar and a queer, mixed-race person, he dismantles the stereotype of gaming as a space for a single type of person, revealing it as a profound landscape for self-discovery.

IN Magazine recently sat down with Guillermo and talked about how games, far from being an escape, helped him understand his own sexuality and find solace in times of hardship. We also explored how video games can lead us to a deeper understanding of ourselves.

Why write about queerness and video games? How do they relate in your life as a gamer?

Games have been unfairly assigned this boogeyman of cis-heteronormyness, which in my experience couldn’t be further from the truth. I mean, games are about role-playing, about hitting our unseeable pleasure-buttons, about playing with others in often impassioned, unhinged ways – screaming, jumping for joy, intensity, laughter. As soon as you boot up Street Fighter

or Mortal Kombat , the first thing you do is decide what kind of gendered – or agendered – person you want to squash your friends with. Games also give us these strange pleasure-shocks of self-recognition when we find ourselves playing dress-up, or romancing a character we didn’t think we’d be attracted to.

I think the way we have thought of games as anti-queer is something invented by big companies who want to sell games as children’s toys, and restrict their meanings for their own benefit. Of Floating Isles confronts this question I’ve wondered all my life: how can we have this daily habit involving play, interaction, pleasure and experimentation, and not see it as queer?

You return to queerness throughout the book, though the book is also about growing up very religious, as Filipino American, and facing many hardships, including the loss of loved ones. How do you see queerness formed through all these moments? Some chapters focus on sex, gender and queerness, but you’re right that I don’t isolate queerness as one form of difference in my life. I think that’s because I’m ‘queer’ from what we see as ‘normal’ in a multitude of ways, and they are all part of being queer, too: I am neuroqueer (as neurodivergent people are often read as queer), I am Asian-queer (as Asian men in North America are particularly read as effeminate and queer), and gender-queer as well. I think for those of us who have multiple ways of diverging from the norm – and being excluded, othered – our queerness becomes invisible, as people tend to centre on other things, like our poverty, our immigration status. But for most queer people in the world – non-white, non-Western – queerness is rarely an isolated identity we get to claim. And for me, video games really spoke to that ambiguity, that mixture of otherness that we have

a hard time explaining to others. Video games have always been queer, as the game scholar Bo Ruberg writes, but they have also always been meaningful as a space where participants don’t need to declare their identity at the door, or even have it all figured out.

Can you give examples of ways games helped you understand your own sexuality?

Chapter 2 of the book contains intimate moments I had with chatroom role-players, where, years before I even had my first kiss, I experimented erotically with anonymous people playing characters from the game Final Fantasy 7 – I was the pony-tailed hot mess, Reno. Later in the book, in Chapter 8, I talk about the term ‘player-sexual,’ which explains how in some games, the player can romance almost any significant character, no matter their gender or sexuality. I think of how ‘player-sexual’ can make us think differently about the cycles of being bisexual – the ‘bicycle’ – and how bi-erasure often comes from a fear of bisexual ambiguity, of uncertainty, which can make bisexual/pansexual people seem a threat to both straight and gay people. Yet in many modern role-playing games, bisexuality is almost a default, and it’s a given that you as a player can go any which way, that you could respond to anyone’s ‘dire warning about the yonder dragon’ with a salacious flirt. I found that this resonated with my sexuality and helped me understand my own attractions.

Much of Of Floating Isles focuses on your experience with suicidal ideation, including moments when you sought to end your own life. How did video games relate to these feelings? Would you say they rescued you in some way? No, I try to be clear that it was people and community and acceptance that rescued me, and then knowledge, learning, love and friendship that helped me find reasons to live. Games cannot rescue us – I try to be clear about that, as I don’t want anyone to walk away from this book thinking games will save us from anything. But when we talk about these things that do rescue us – community, love, support, self-acceptance, knowledge – games are not irrelevant, either. In the fifth chapter I write about how, during a year of suicidal ideation, the game Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind helped me learn to survive by travelling and connecting with others, and by understanding myself better. And many games since Morrowind have helped me understand devastating atrocities and wars around the world, and helped me seek out the political will and solidarity to find hope in those moments – hope that is crucial to our own survival. Still, I don’t want readers to think that games could ever do all the work of saving or condemning us: that’s work only we can do for ourselves. But when we leave games out of these conversations about health, spirituality, meaning and death, we exclude so much possibility for growth and understanding, and in the end we only hurt ourselves.

Your eighth chapter focuses on the different concepts of gender formed through games, focusing on the work of trans designers and scholars. What did this work mean to you in your life experience with games?

In 2016, I started playing the game Overwatch, a game full of heroes who are diverse in just about every conceivable way: nationally diverse, neurodivergent, racially diverse, gender diverse, queer. I played Overwatch nearly every day for seven years, becoming so familiar with each of my favourite characters (almost all

queer women) that my bodily habits, style and attitude began to transform. I use the concept of ‘blueprinting’ from the scholar and artist micha cárdenas to explore how games like Overwatch don’t just offer positive representation, but help us enact different ways of imagining our own desires, beliefs and habits.

One of my main Overwatch heroes, Pharah, is still, I believe, the only lesbian Arab woman in all of mainstream gaming. In a time when Arab peoples are so often depicted as anti-queer radicals, or ‘terrorists,’ Pharah’s presence really means something, not just because we see her, but because we perform her – we enact her missions, we dress her, and after many hours of playing as her we come to see ourselves through her eyes. For me, the power of video games is in these transformative moments, and I hope Of Floating Isles helps us come to terms with games, and with our messy, queer, gender-bendy selves that games help us create.

Of Floating Isles by Vancouver author Kawika Guillermo is available in select bookstores across the country now.

In his debut novel The Sapling, the Canadian actor shares the profound, life-altering friendship he formed with his teacher

By Stephan Petar

Everyone has stories. Some are publicly shared and others remain exclusive to a person or a small group of people. Some stories are snapshots of one’s life, reflecting a single moment. Others can stretch a lifetime.

Actor Marc Bendavid ( Reacher, Dark Matter ) has held a transformative story for more than two decades, and it’s one that altered his life. It’s a story about a platonic intergenerational friendship between him and his teacher, Klara. The friendship blossomed during a life transition for Bendavid that saw his home dynamic change and the realities of adulthood begin to take shape. It’s a narrative those closest to the performer have only heard or experienced snippets of.

When he learned Klara was dying, the realization that his memories of this delicate relationship could be lost dawned on him. “I felt this sudden pressure that I was now the sole caretaker of all these very special memories; that on the approach of Klara’s death I would be the only one to have them,” he shares. “I wanted to write them down, so as not to forget them myself.”

He wrote down a collection of moments between the two as he was grieving. These eventually became the subject of his debut novel, The Sapling. The autobiographical fiction has been described as “incredibly delicate” and “tender.” It’s not only a tribute to their friendship, but a tale illustrating the fragility of memories.

Bendavid met Klara when he was in the sixth grade. He was 11 years old, and she was 43. Klara, an immigrant from South

Africa, was an art teacher at his school. The book documents their connection, which involved lengthy phone calls, letters exchanged and photography excursions into nature.

As the tale progresses, readers witness the evolution of their friendship. It becomes infrequent as Bendavid moves to high school, to university and into adulthood. When he learns Klara is dying, the narrative explores his coming to terms with her impending death, the moments they shared and his grief. Providing a glimpse into an unusual bond, its loss and the questions it raises.

When we sat down with Bendavid, he explained how he unlocked these memories and what writing process he adopted to complete the book.

memories…

“So many questions now, all rushing headlong into the same answer: I don’t remember ,” Bendavid writes in The Sapling The sentence illustrates how fragile our memory can be; how it can begin to fade over time. Throughout the text, Bendavid isn’t afraid to contemplate these lost moments. He even poses questions, which seem to be prompts to help him potentially regain them.

While the author did recall key moments, other details about the decades-long friendship re-emerged when he least expected. After learning from Klara’s daughter that Klara was dying, Bendavid began experiencing vivid dreams that he mentions in the novel. He describes them as “very intense” and appearing every night for a few weeks.

“I would wake up in the middle of every single night for two weeks with these memories,” he says about that section of the book, noting it wasn’t an exaggeration. “ It was as though once I fell deep enough asleep, pages of a book were held in front of me and I could just take notes.… It was that vivid.”

He jotted down details over months, documenting whatever began flooding back. “I would remember a conversation or an outfit or a piece of art,” he shares. “I would write them down and a lot of times they were a couple of lines or a paragraph handwritten on a piece of paper.”

Given the distance, and being closer in age now to the adults around him at the time, it seems Bendavid re-evaluates moments from his past through a different lens. In one recollection, he recalls a family acquaintance raising suspicion about the friendship. He admits the moment made him feel shameful and horrible at the time. “If it seems obvious today, even commendable, that an adult might feel obliged to ask this of a child in my circumstance, I simply couldn’t believe it then,” he writes in the book.

Even when he believed every stone had been turned, new memories emerged during the editing process. “I think because I forced myself to be in the space of this story for so many days, hours and months that things just wafted up through the floorboards.”

The way Bendavid recounts these moments and illustrates the influence it had on him will no doubt have readers evaluating and exploring the bonds they hold or have held – reminding them to value every moment as well as encouraging them to share their histories. While the book is now in stores, it’s likely the author will continue excavating memories of this time in his life for years to come.

Turning life fragments into a story…

Though The Sapling is Bendavid’s first book, he’s been writing poems, short stories and essays his whole life. But those works never went anywhere. “I never really finished anything properly.… I would just abandon things,” he reveals, noting he did finish a novella. “I have this graveyard of unfinished projects around me and I wanted to finish something to the end with this.”

To prevent The Sapling from ending up with his other projects, he entered a strict writing routine. “Monday to Friday, four hours every morning. I’m locking myself up in a little office,” he says about his writing process. “If I can’t write or am too tired or unfocused, then I read. I have to be with written words in some way or another.”

His partner, actor François Arnaud (Midnight Texas, Yellowjackets), played a major role in helping him focus. “He was an essential part of my discipline,” Bendavid shares, noting he gave Arnaud strict parameters not to disturb him unless there was an emergency. “He kind of shepherded me when I was reluctant, or told me to get back to work.”

Bendavid credits his writing discipline partly to his acting profession, noting an actor’s persistence and endurance. When asked if his passion for gardening helped, he agrees that it did, although he admits he had never thought about it before.

“What you do in a garden is you go back. You keep going back to the same part with the same plants and do the same thing.… You trim or you feed or you water or you transplant,” he explains. “You’re always going over a landscape that’s more or less the same to observe the little changes.” He likens this repetitive gardening practice to reworking chapters during the editing process.

When it came to choosing a title, he had a list of options. In the end, The Sapling felt right. It encapsulates his passion for gardening, his love of nature, and a specific memory. It is also a nod to the moment in his life when he met Klara, as “sapling” also means a young person.

The book introduces an unconventional friendship that many may not agree with. “These kinds of friendships can occupy a potentially powerful position and that’s also why they’re potentially dangerous. It is essentially a power dynamic that’s out of whack,” Bendavid says. “If the adult in that dynamic has your best interests at heart, it permits you to grasp a sense of identity and self-possession that can be more powerful than what we give kids at 13 and 14.”

Overall, the book is a contemplative read. It may have readers examining the relationships in their life, searching for memories and seeing them from a new perspective.

There’s a certain kind of prejudice in this world, and it isn’t pretty…

By Jesse Boland

If nobody today told you that you’re beautiful, it’s probably because you’re not.

If that statement was upsetting for you to read, then you should probably just close this tab now, because the rest of this article is about to get really ugly. And, yes, I will be using the word “ugly” frequently – because the phrase “not conventionally attractive” is

simply too delicate to properly limn the significance of what will be discussed, as well as because I’m on a word count here. When we use words like “beautiful” and “ugly” to describe people, we are referring to the polar ends of the spectrum of attractiveness as well as the beneficiaries and victims of lookism. And if that term is a new word for you, get ready for a journey of perspective as we jump into the deep end of the pool of superficial shallowness.

Lookism refers to the prejudicial, discriminatory bias of people based on their level of physical attractiveness. It is one of the underlying discriminations of other types of intolerances such as racism, misogyny and ableism, as well as their subbranches such as featurism, colourism and fatphobia. Yet despite being such a fundamental foundation of so many forms of oppressive intolerances, lookism is rarely mentioned in either academic studies or HR anti-discrimination training. And that’s for one major reason: it’s ugly to talk about ugliness. Acknowledging that somebody, or even yourself, is unattractive is perceived as being shallow and superficial when, really, it is simply addressing the wildebeest in the room that everybody with two eyes can see.

Being considered ugly is deemed as being the most horrendous appellation a person can be, so much so that it has even morphed the actual definition of the word. The original etymology of the word “ugly” stems from the Norse word ugga and then uggligr, which means “to be dreaded,” whereas “beauty” comes originally from the Latin word bellus, meaning “to do, show favour, or revere,” before they both eventually evolved into the words they are today being qualitive terms for physical attractiveness. Now, with the knowledge that being ugly is perceived as such a hindrance that it literally means “to be dreaded,” and being beautiful is such a virtue that it is synonymous with reverence, is it not safe to say that a person’s level of physical attractiveness may determine their lived experience in society? If we can acknowledge that being pretty is a privilege, would that same logic not deduce that being ugly is handicap?

The thing about beauty and ugliness is that it is so difficult to discuss, because we like to pretend that beauty/ugliness is in the eye of the beholder, when deep down we know that is not the case. Beauty is technically subjective, much like art, where it is open to interpretation and cannot be specifically defined, and therefore there are truly no “good” or “bad” looking people. But let’s be real with ourselves. Similar to art, there reaches a point of universal acceptance that something is good or bad despite its subjectivity. The Godfather is a good film, Katy Perry’s “Woman’s World” is a bad song, and any other opinion is void.

The same can be said for a person’s perceived level of attractiveness, which can be understood in something I have coined the “’90s Sitcom Blind Date Test.” Imagine an episode of Friends where Ross is supposed to go on a blind date with somebody that Phoebe set him up with; he goes to the door to greet his date and sees her for the first time. If the door were to open and the woman on the other side were to be played by either Cameron Diaz or Kathy Bates, we would immediately know, from the initial visual alone, exactly what the joke is and what the following story of the episode is going to be. If the door opens on Cameron, then Ross scored big but is probably going to mess this up; if it’s Kathy, then he is in trouble and we gotta see how he’s going to get out of this one. Hotness and ugliness are objective signifiers in visual mediums so much so that actors are sometimes literally credited as “Hot Guy” and “Ugly Friend #2” in castings. At a certain point, denying a recognition of someone’s blatant level of attractiveness is akin to saying, “I don’t see colour.”

Still not convinced? Think of the ways in which particular behaviour is either tolerated or punished based on the person who is doing

so, and why that might be. Confidence may be considered the true test of beauty, but the true measure of ugliness is audacity. For people who are not fully secure in their appearance, it may be daunting to put themselves out there by posting a selfie or wearing a sexy outfit in public, but we as a society have at least been taught to celebrate people for being “brave” in pushing themselves out of their comfort zones and not say anything mean about them…as long as they’re nice. But when an ugly person has the audacity to be rude, mean or aggressive, the gloves come off, and we are seemingly given the green light to say the quiet part out loud and tell them what we’ve been holding in since we first laid eyes on them.

Lizzo was celebrated as the body positive queen of self-love for years because her image was that of a kind, funny, empowering person, so much so that we forgave her for not being conventionally attractive because of her weight and teeth. But the moment allegations were made in 2023 by her former dancers and creative director that she had created a toxic and emotionally abusive work environment, the public perception of the endearing fat woman went out the window, and people felt they were vouchsafed permission to hit ‘send’ on the nasty drafts they had been writing in their heads for years.

You have to pick a struggle; be ugly on the inside or the outside, because if your spirit matches what we see in front of us, you will be put in your place. And best believe, there is an unspoken place for people who look the way you do.

If reading this has maybe hit a little close to home for you because you’ve realized you are either a victim or a perpetrator of lookism –good. The first step in combating this discrimination is to accept that it does in fact exist systemically, and that we are all hegemonically complicit in it. But just as addressing our subconscious racism or internalized homophobia is integral to unlearning our unconscious biases, the same can be done for dismantling lookism. Questioning why we approach certain strangers at parties and not others, reevaluating who we follow on Instagram and how that shapes our perceptions of what the average person is supposed to look like, and unpacking if someone is actually a nice person or if they’re just hot and smile when they speak – these are just some of the ways in which we can begin to combat our own prejudices and overcome the oily, wrinkled skin barrier of ugliness to recognize the human underneath it.

If you’re still reading this, I can only assume that you’re ugly –because a hot person would likely have been distracted by now by a DM from someone asking to have sex with them, but you weren’t. Accepting that beauty isn’t one of the gifts your parents left for you under the genetic Christmas tree is a tough pill to swallow, but it only proves that every other gift you have is a gift that you have earned. If people say that you are funny, kind, intelligent, charming or cool, you know they actually mean it, because they’re certainly not saying that just to sleep with you. Ugliness isn’t a curse, but it is a struggle, and it’s one you somehow manage to overcome every day, because it doesn’t define you that you don’t have the unfair privilege of beauty. If nobody today told you that you’re beautiful, it’s because you’re so much more than that.

The feature film debut of CSA winner Sasha Leigh Henry not only challenges the conventions of the “hangout” story, but sheds light on a Black queer narrative rarely seen in Canada

By William Koné

I love friendship stories. For me, they’re the most compelling films and television series because they invite writers to explore themes surrounding the human condition through multiple lenses. Friendship stories create conversation by showcasing different characters navigating emotional challenges in their own unique way. It’s a narrative tool that encourages you as a viewer to hold empathy for what these characters endure, even if you don’t relate to them. This normalizes our lived experiences onscreen. It’s the reason films like Waiting to Exhale, First Wives Club and The Best Man continue to resonate with people today.

“Hangout” stories elevate the genre by depicting quality time among friend groups within a specific setting. This was evident in TV with The Golden Girls, Living Single, Friends and Sex and the City as these characters mingled in their homes or at a local

eatery. Conversations among these friends ranged from career aspirations to sex, to aging, to life satisfaction. The locations where the conversations took place became characters themselves. A connection was built between the viewer and the characters as the viewers watched these intimate exchanges strengthen, or hinder, the friendships.

Unfortunately, hangout stories have declined in recent years, despite the longevity they achieved decades earlier. Cultural historian Bob Batchelor has noted that streamers are less invested in the genre, as it takes longer for audiences to latch onto them. This is evident with the string of Black American hangout series that have been cancelled after three seasons or less, such as Run The World, Harlem, Grand Crew and South Side . In Canada, hangout content is even scarcer: Bellefleur is the only current

scripted example on air. Meanwhile, hangout stories centring Black folks remain a rarity in our country. This creates a visible gap among new generations seeking stories centring the highs and lows of friendship.

Having said all that, when I attended the Toronto International Film Festival this year, it brought me great joy to learn that Sasha Leigh Henry’s feature film debut, Dinner with Friends, is, in fact, a hangout drama! I have admired Henry’s work since her short film Sinking Ship and the CSA-winning Bria Mack Gets a Life; her humanistic writing style often showcases the humanity of Black Canadian life.

Drawing from classic hangout films like The Big Chill and Diner, Dinner with Friends follows a group of Torontonians as they grapple with the pressures of adult living and the growing fractures within their bond. Through the course of many years, they convene at different dinner parties where difficult truths about their evolving identities and their wavering friendship emerge.

What distinguishes the film from its predecessors is its predominantly Black cast. In casting Dinner with Friends, Henry said, “The motivation was to create roles that would untether Black people from the strife of our identity. We don’t get to exist [onscreen] without it being some conversation about our race. What can I offer into the canon of storytelling that tells you something about us, while broadening the scope of what’s possible for us?”

In depicting queerness in Dinner with Friends, Henry’s intentions were different. “It was important [to include queer characters] because there are eight friends in the film,” says Henry. “Most of my friend groups have at least one queer person in them. We just don’t have enough decent representations of Black queerness that aren’t about their coming out story. I wanted to offer that freedom for those performers when we cast Josh and Ty.”

“ DRAWING FROM CLASSIC HANGOUT FILMS LIKE THE BIG CHILL AND DINER, DINNER WITH FRIENDS FOLLOWS A GROUP OF TORONTONIANS AS THEY GRAPPLE WITH THE PRESSURES OF ADULT LIVING AND THE GROWING FRACTURES WITHIN THEIR BOND.“

Henry and her screenwriting partner Tania Thompson expanded that thought further by including Black queer characters in the film. Josh and Ty (played by Leighton Alexander Williams and Michael Ayres) are a couple within this predominantly straight friend group, but their characters aren’t reduced to the “gay best friend” stereotype. Their relationship and their perspective carried as much emotional weight in the narrative as their hetero counterparts. This was quite refreshing to see, as hangout films historically didn’t feature queer characters in the core friend group. For example, Matthew Laurance’s character Ron in St. Elmo’s Fire was Demi Moore’s flamboyant neighbour, but his character lacked a point of view. Ron served as a comedic gag and an eventual plot device to confirm Andrew McCarthy’s heterosexuality.

In playing Josh and Ty, Leighton Alexander Williams and Michael Ayres stress that very point. “It’s always been my dream to play fully realized characters, regardless of their sexuality,” Williams states. “Being trusted to bring a strong queer character like Josh to life was truly a gift. While Josh can be sharp-tongued, hotheaded and cantankerous…he’s also hilarious, loyal, honest and charismatic. Those are my favourite types of characters!”

“It was so rejuvenating to be a part of this film,” Ayres shares, “to play a queer character who isn’t defined by a struggle with their queerness. Ty’s and Josh’s queerness and their Blackness is a fact rather than an issue, which is kind of subversive.”

What drew me to Dinner with Friends was the exploration of grief surrounding fractured friendships. Grief Theory describes loss in two ways. Primary losses describe the event that elicits a devastating change to one’s life, such as a death or a breakup, while secondary losses are the residual changes surrounding that event, such as a change in identity or a change in beliefs. While hangout stories often follow friendships thriving over time, Dinner with Friends challenges that trope by highlighting the pain of estranged bonds. This is especially true with Josh and Ty’s story, as they contend with the disconnect between their aspirations as a queer couple and the aspirations of their straight friends. As the only characters without desires for parenthood, both question whether there’s a place for them in the group as they continue to pivot from heteronormative milestones. It’s a harsh reality that many 2SLGBTQI+ folks contend with, but such a nuanced perspective often isn’t considered in stories featuring predominantly straight characters.

“The film hits close to home because I’m in that phase of my life right now,” says Ayres. “I’m on a totally different trajectory than many of my friends, not just because I’m queer but because I’m living as an artist. You don’t always get to take everyone with you when you move into new chapters of your life. It gets harder to close the distance between you and the people you thought you would always be in proximity to.”

Williams drew from his own experiences to portray this emotional conflict in Dinner with Friends. “I’ve had friends who I loved deeply, but life pulled us in different directions because our values no longer aligned. As a result, those friendships came to an end. Losing friends in real life helped me fight to hold on to the ones Josh had [onscreen],” Williams notes.

Showing these characters contend with the isolation of queer life, I argue, elevates hangout stories by unpacking what is needed for 2SLGBTQI+ folks to be seen as their authentic selves within straight spaces. This is a need that I believe is fundamental for any lasting friendships, regardless of sexuality.

True-to-life characters

As characters, both Josh and Ty are compelling. Beyond the playfulness they present onscreen, what I appreciated most was their ability to be unapologetically feminine and masculine in their gender expression without judgment from their peers.

“Yes, their environment in this film is extremely straight, but it’s still a safe space for Josh and Ty to move through,” says Ayres.

“They’re never in danger among their friends, which is nice.” As a couple, Josh and Ty’s dynamic carries a yin-and-yang quality. While Josh possesses a simmering yet sensitive bravado, Ty is quietly perceptive based on his observations of those around him.

This is highlighted during the film’s climax, when an altercation finds Josh and his straight friend Joy (played Tattiawna Jones) exchanging verbal blows because of their conflicting lifestyles. It is Ty who consoles and challenges Josh after the fight, allowing viewers to witness the loving nature of their relationship. “It’s one of my favourite scenes I shot with Michael,” Williams states.

“Their [Josh and Ty’s] argument exhibited emotional intelligence and a great deal of listening from both men. We can see why they

work as a couple and why they have the strongest relationship in their friend group.” Ayres seconds his scene partner’s remarks.

“The two of them are the sturdiest pair out of all the couples in this film. You can really feel how much they love and support one another, even as they disagree and get on each other’s nerves. It’s aspirational without being unrealistic. Their relationship is kind of a dream.”

Ayres’ point was one of my key takeaways as I left the Dinner with Friends screening. I was reminded that film has the power to be impactful and aspirational at the same time. It’s a temporary escape into a world of possibilities that can instill hope within our lives. As a screenwriter and as a Black gay man, I’ve been longing for stories like Josh and Ty’s to legitimize a queer way of being that offers compassion through our personal journeys. When you don’t see images of yourself reflected in media, a sense of despair persists as you question whether there’s a place for you to thrive in life. It felt inspiring to witness Henry successfully fight to make a film that not only advocates for Black folks’ triumphs and pains within friendships, but also spotlights love among Black queer folks as they stand firmly within their authenticity.

“I hope we see a variety of stories including Black queer bodies. That our characters experience joy, love and success. I’m ready for a renaissance of storytelling where Black queer characters exist in different stories. We deserve light-hearted romcoms, more queer folx falling in love, and badass Black queer superheroes,” Williams comments. Ayres, in discussing his hopes for Black queer storytelling, also strives for diverse representation. “I want to see complicated and unlikable Black queer characters onscreen, who are allowed to be messy and make mistakes. I want to see myself reflected in the entirety of my experience as a person. There is space for different kinds of struggles beyond identity. There is space for stories where we don’t have to be on our best behaviour.”

As the fate of hangout stories continues to loom, Dinner with Friends stands as a welcomed addition to the canon. The film reminds us that in maintaining curiosity for new perspectives within friendships onscreen, there’s room for the legacy of the genre to grow and to be celebrated.

IN Magazine talked with the Looking actor to discuss what drew him to play a closeted American man in Plainclothes, plus the danger of public sexual interactions, and the loss of queer signalling during the Grindr age

By Matthew Creith

by

NEOSiAM

As awards season is fast approaching, Russell Tovey’s name might be at the top of many insiders’ lists to not overlook. In Plainclothes, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, the Looking heartthrob delivers a quietly powerful portrayal of a closeted New Yorker named Andrew who is navigating desire, vulnerability and survival in 1990s America. This was a time when undercover police were often tasked with entrapping gay men in public situations when they sought connection with other men, behaviour that was criminalized.

Directed by Carmen Emmi and co-starring Tom Blyth as Lucas, an undercover officer tasked with entrapping gay men, Plainclothes is an erotic thriller that lingers long after the credits roll. Lucas finds himself drawn to Andrew, a man who not only must steer away from societal danger but also offers tenderness and care during what might be Lucas’s first experience of love, lust and intimacy.

IN Magazine had the opportunity to talk to Russell Tovey when the film premiered theatrically this fall, to gain his insight into the experience of making such a unique movie and what modern gay dating is like compared to 1990s-era America.

I had the chance to watch Plainclothes at Sundance, and I’ve been wanting to talk to you ever since. Before dating apps, gay men often faced real risks just to connect with other gay men. What drew you to Andrew as a character navigating that world?

What drew me to Andrew, and what always draws me to a script, is the dialogue. Within a few pages, I was like, ‘I need to say these words. I want to inhabit this person.’ I’ve always had a slightly romantic notion of Syracuse [where the film was shot]. We had a very beautiful time there, and I was just very excited to be filming upstate in an area where the writer-director was from. He was working with all his family and friends who were up there, and there was something really wholesome and special about that.

I’m very much drawn to queer stories, and Andrew was unlike anyone I’d played before. His struggles, his need for connection, and the way he navigates the world I found fascinating, enthralling and exciting. I loved the idea of being a character that is enabling or facilitating someone else’s first experience, and how you approach that, and the responsibility of that.

It felt beautiful. I really pushed for this: Andrew makes sure that Lucas has a very loving, kind, generous first experience. It was fundamental to me that the first experience was safe, that sex was safe, that the communication was safe, and that he was very clear with him. There was no ghosting, as we’d say now. They wouldn’t have said that then. But in this relationship, however long it lasted, I felt like Andrew wanted to give Lucas something that he wouldn’t be traumatized by. So many people’s first experiences are very traumatic, very selfish, and this was something that I found beautiful.

You’ve played several queer roles, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Looking. That show was transformative for me personally. I wasn’t out when I first started watching,

but I came out during its run, and I don’t think that was a coincidence. Seeing gay men in relationships and friendships that evolved over time really mattered. How did Plainclothes feel distinct in its depiction of gay men’s experiences?

Well, when safe spaces are taken away and representation is minimal, queer people are pushed to the margins into dangerous scenarios. This isn’t that dangerous a scenario that they’re in, but because of society, because of timing, there isn’t freedom for living authentically. People are pushed into these dangerous places. I feel like this film is indicative of that. It’s based on a true story of gay men being targeted. That’s shocking, and it feels like it should be a historical piece. But the way the world goes, it’s cyclical. The conversations that are happening here [in the United Kingdom], versus over where you are, are quite frankly terrifying.

I don’t think when we were making this film that we realized the enormity of what it is. It doesn’t feel like a historical piece; it feels contemporary.

“ I LOVE THE WAY QUEER PEOPLE INTERACT IN SAFE SPACES. IT’S A BEAUTIFUL THING. FLIRTING, CONNECTIONS, MEETING STRANGERS, STARTING CONVERSATIONS. THAT’S BEAUTIFUL. IN MY LIFE, THAT ISN’T LOST. I’M NOT SOMEONE DEEP INTO APP CULTURE.”

Especially for younger audiences who didn’t live through that era, how important is it to revisit that history?

For me, as Russell, knowing our history is imperative. Knowing the shoulders of giants that I can stand on. Especially trans women and trans people, I feel like I have a responsibility with my platform to amplify their stories, to cite sources, and to pay homage to them. I’m only here because people did this work before me. I hope people will watch this and learn, and want to go off and know more, and want to know about their history.

I feel like we, as a community, have an inherited trauma, and we need to know what’s happened, and what is happening, to understand it. What mistakes were made in the past, how they were overcome, and where we’ve got to now. It doesn’t feel like there has been an opportunity for that education to stick.

I hope people also feel that this film is beautiful, and it’s a universal story about unrequited love, and the need to police one’s feelings because of society. I want people to feel touched. I’ve had a lot of people who have seen the film say these characters live beyond it with them. They care about them. They want to know if they’re okay. They want to make sure they’re happy. It’s a beautiful story.

The film also captures the paranoia and coded signals of cruising culture: silent exchanges, glances, gestures. I remember that myself from going out, and it feels very different from today’s swipe culture. Do you think something’s been lost with dating apps replacing public spaces and bars?

I think IRL is so important. But a lot of those things still exist. I still really trust the two-and-a-half-second, three-second rule: look back, and then it’s on. I love that. I’ve always been fascinated by that. I love the way queer people interact in safe spaces. It’s a beautiful thing. Flirting, connections, meeting strangers, starting conversations. That’s beautiful. In my life, that isn’t lost. I’m not someone deep into app culture. It’s impossible for me to a certain extent, but I love IRL connections for sure. I hope we don’t lose the ability to flirt.

Absolutely. What do you hope audiences, gay and straight alike, take away from Plainclothes, especially about the risks gay men faced just a few decades ago?

There are many things I want people to take away. I want people to discover Carmen Emmi as a brand-new talent. I want people to discover independent films. This was made for hardly anything, by people who believed in it and were passionate about it. It’s having such a beautiful response and impact. I want people to be inspired by that and get behind independent film and storytelling of this level.

I want people to see representation of themselves on screen, to see possibilities, to see characters that allow them – like you said you had with Looking – to find their authentic truth. I want people to be entertained. People ask a lot about the sex scenes, but I feel like the sex scenes here are universal. It’s the human condition. The things I’m drawn to are stories that, especially in today’s climate, help us find similarities rather than differences. I want people to watch this film and see similarities in these characters that they feel in their own lives. We all feel the same things. We all long for the same things. We all desire and need and deserve the same things, however we feel about other human beings, whoever we’re attracted to. I want people to see the similarities in these characters in their own lives.

It really is such an erotic thriller with a lot of heart. In today’s Marvel-heavy film landscape, having an independent film like this break through feels rare and refreshing. Thank you. But you see, for example, with Plainclothes, we’re so fortunate to get a theatrical release. Then it’ll end up somewhere

online, on a streamer. But the real stories, the places where we find the realities of life, are in independent film. I’m proud to be part of this season of independent films that are coming out. There are so many brilliant voices, performances and storytellers. It’s really exciting, but it’s also very important that we support that.

Looking beyond Plainclothes , I’ve noticed you’ve been promoting The War Between the Land and the Sea on social media. What can you share about that?

This is written by Russell T. Davies. It’s a new five-part series for Disney and BBC. It’s a Doctor Who spin-off, so it exists within that umbrella. It will be out at the end of the year or the start of next year. I play a character, Barkley. He’s someone very lowly in an office, booking people’s taxes, overlooked and slightly ignored. He’s a drifter, going through the motions. Something happens, and he’s given the biggest responsibility ever.

I loved it. I’m really proud of it. I’m really excited about it. It feels exciting and important, and it has an important message, which I’m not allowed to read or talk about yet. But I’m incredibly proud and excited.

That sounds fantastic. Russell, thank you so much for your time, and good luck with Plainclothes. I’m excited for more people to experience it.

I’m really moved that you felt Looking changed you, because it changed me as a person and as an actor. I’m proud of that, and that’s the show I can watch, even though I’m in it, as a fan. That doesn’t happen a lot. Those characters still live with me. Doris! Where’s Doris?

I love her. Any time she pops up, I can’t wait to see what she does.

Why isn’t she the biggest fucking thing on the planet? She is just amazing. She’s an amazing artist as well. She makes great paintings. Lauren [Weedman, the actor who portrays Doris] is heaven, and I didn’t have enough scenes with her. I kept saying to [Executive Producer] Michael Lannan, ‘Please put me in more scenes with Doris. There’s no need for me to hang out with Doris, but please!’

We can only hope for a reunion of sorts! Thank you for speaking with me today, Russell! Cheers!

A conversation with actor/writer Drew Droege about his newest play, which takes a stab at unhinged white gays on the loose

By Elio Iannacci

Drew Droege was born to be invited to brunch. His stories about being raised in the American South, living in Los Angeles and surviving the rigours of La La Land’s casting chaos are best heard over mimosas or Caesars (that’s Bloody Marys in America). His addictive storytelling is partly how so many queers – me included – got through the pandemic: we listened to his podcast Minor Revelations , with guests ranging from Bowen Yang to Fortune Feimster, or hopped onto YouTube to watch clips of him embodying the pretensions and peculiar wisdoms of actress Chloe Sevigny (with a swarthy yet cutting “Good Evening America”). For TV fans, his slew of credits includes Hot in Cleveland and Grey’s Anatomy

His cameo in Luca Guirdinin’s Queer reintroduced the South Carolina–born talent to Hollywood’s always-slow-on-the-uptake casting directors. Theatre audiences, however, already knew what kind of brilliance he brought with the biting, witty and prescient plays he wrote and starred in, such as Happy Birthday, Doug and Bright Colors and Bold Patterns – both exposing modern gay life as fragile, radical, hysterical and histrionic.

His most news-inducing production, Messy White Gays (now in New York City until December), plays to his strengths once again. The cast includes the just-as-sharp Pete Zias, the gorgeous Derek Chadwick, and the always-beguiling James Cusati-Moyer and Aaron Jackson. Each is well chosen to blow up the twisted gay archetypes Droege writes, down to smithereens. The show’s set-up says it all, as it begins with a throuple that goes from three to two when one pair kills the odd man out. The press release for the play is already one for the books, stating:

“It’s Sunday morning in Hell’s Kitchen. Brecken and Caden have just murdered their boyfriend and stuffed his body into a Jonathan Adler credenza. Unfortunately, they’ve also invited friends over for brunch. And they’re out of limes! Feel bad for them! They’re MESSY WHITE GAYS!”

It makes sense that brunch is the backdrop, because Droege’s best work (whether on stage, screen or podcast) has the same flavour: sharp gossip, unfiltered honesty and boozy outrageousness, best savoured when the world is still a little hungover.