3 minute read

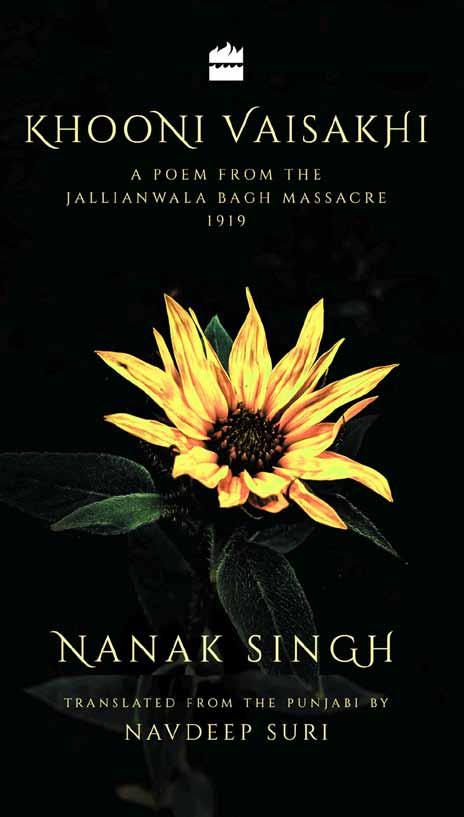

‘fire and fire and fire they did’

from 2020-08 Melbourne

by Indian Link

A poem from the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, 1919

Like birds from the woods, they flocked together

So the hawk could have his fill, my friends. To quench Dyer’s deadly thirst With streams of blood their own, my friends. Ah! My city mourns with grief today

Happy homes lie shattered because they go. Heads held high offered for sacrifice For Bharat Mata’s pride and honour, they go. Pray, stop these valiant souls of God! Straight to the abyss, they rise and go.

O mothers, watch your precious sons

To give up their youthful lives, they go. O sisters, hold back your brothers dear You won’t see them again once they go.

O wives, hang on to your dear beloveds Or you’ll spend your lives widowed, if they go.

O children, go run and hug your fathers

’Cause you’ll be orphans if they go. Stop them, hold them, do what you can They won’t come back, once they go. Says Nanak Singh, Can’t stop them now For nation’s sake to die they go.

Five-thirty sharp the clock had struck Thousands gathered in the Bagh, my friends. Leaders came to lament the nation’s woes Taking turns to speak out loud, my friends. Voiced grievance, hardship, anger, sorrow Saying, no one listens to us, my friends. What can we do, what options left?

Can’t see any ray of light, my friends. Those words forlorn, they barely voiced Came soldiers thundering down, my friends.

At Dyer’s command, those Gurkha troops Gathered in a formation tight, my friends. Under the tyrant’s orders, they opened fire Straight into innocent hearts, my friends. And fire and fire and fire they did Some thousands of bullets were shot, my friends.

Like searing hail they felled our youth A tempest not seen before, my friends. Riddled chests and bodies slid to the ground Each one a target large, my friends. Haunting cries for help did rend the sky Smoke rose from smouldering guns, my friends.

Just a sip of water was all they sought Valiant youth lay dying in the dust, my friends.

That narrow lane to enter the Bagh Sealed off on Dyer’s command, my friends. No exit, no escape, no way out was left Making the Bagh a deathly trap, my friends. A fortunate few somehow survived While most died then and there, my friends. Some ran with bullets ripping their chest Stumbling to their painful end, my friends. Others caught the bullet while running away Dropping lifeless in awkward heaps, my friends.

In minutes, the Bagh so strewn with corpses None knew just who was who, my friends. Many of them did look like Sikhs Amid Hindus and Muslims plenty, my friends.

In the prime of their youth, our bravehearts lay Gasping for one last breath, my friends. Long hair lay matted in blood and grime In slumber deep they sleep, my friends. Says Nanak Singh, Who knows their state But God the One and Only, my friends.

Poonam was the main one in her family in whom her mother confided. The stories started when Poonam was just a child; she thinks she was younger than her daughter is now. Most parents read books to their children before they sleep. Nirmal’s bedtime tales were of growing up in Lahore, the journey she made to India and the experience of being a refugee. She was not always judicious in the amount of detail she shared. Early on in her life, Poonam had a sense that something terrible had happened to her mother.

In the retelling of Nirmal’s experiences, it was as if she were reliving it all again. ‘It was part of our daily lives… It was the formative experience of her life and in a strange way it became the formative experience of my life because she spoke about it all the time.’

Poonam does not think of it on a day-to-day basis now, but says partition defined her because it so utterly defined her mother, and shaped who she became. ‘Partition is always there in the background.’

In the last years of her life, Nirmal lived in this family home, cared for by her daughter. Photos of her with her beloved grandchildren are on prominent display in the kitchen. Nirmal, or Nimmi as she was known, began her life on the outskirts of Lahore, born into a middle-class family in 1929. She spoke of her pets: the rabbits and dogs. Her family were Hindu, belonging to the Arya Samaj sect, which rejects idol worship and promotes equality of women.