Order

Most people today are housed instead of creating their own homes. The natural process of defining what dwelling means for oneself is replaced by designs informed solely by statistics, and standards. The innate sense of belonging to your own dwelling needs to be restored with a proper framework providing order as well as inspiring individual expression. Architects should make way to give way

Spaces of human habitation are mostly defined by architects and most of what architects design are for humans. Therefore both have to teach and learn from each other, most of the time architects see their role as a “teacher”. In reality, it is only after people start using a building that Ideas take on meaning through lived experience, and all decisions are accurately evaluated. Not only should architects learn from users, but they should also give way for individual decisions. Lucien Kroll reflects in a dialogue with Reinier de Graaf in “Four walls and a roof”: “According to Vitruvius, the Roman master builder, architecture was the combination of three virtues: Utilitas, Firmitas, and Venustas. He forgot Humanitas.... That, I felt, needed changing?”1

roof for a market on a first floor of a Soviet block

Humans may not understand their own needs from a home until they have lived in it for years, it is impossible for architects to design spaces that support individual lifestyles in large scale projects. In his book “Lessons for Students in Architecture” Hertzberger articulates“Because we can never learn what each person really wants for himself, no one will ever be capable of inventing for others the perfect dwelling”,2 nobody should be forced to conform to a particular lifestyle inspired by the most common projections of human life. “Everyone should at least be free to give his personal interpretation to the collective pattern”3 (Hertzberger). An architect should incite better decisions and ensure order, but he should not over-encourage. The goal is to find a balance where individuals have the space to explore and create their own unique lifestyles, and architects provide a framework where they encourage just enough

Nowadays, it appears that only extreme opposites exist, leaving little room for anything in between. A useful comparison is the contrast between massproduced playgrounds and makeshift forts. Municipal parks in Georgia lack insights into communities, and are rigid and uniform, with standardized units distributed everywhere without context. Features like stairs, slides, and pathways dictate specific movements, limiting kids to the architect’s intentions. In contrast, makeshift forts empower kids to explore the potential of available materials and circumstances, even if they are basic and limited, children create their own movements, and scenarios, turning simple items into tools for imaginative play. These given properties are musical instruments, not the music itself.

A large amount of preconceived uses might be harmful for individual creativity. Architecture should not be looked at as a finished product delivered to its user, it should have properties that allow users to define the product themselves. “In consumer goods, production is followed by consumption. But there are totally different requirements to be fulfilled in the field of housing; requirements which do not ask for products, but which are themselves productive or creative.” 1

The above-mentioned mass-produced playgrounds might resemble Soviet mass-housing blocks, in this case, the lived experience clearly indicates that sometimes boundaries and restrictions are what forces people to be more individual, however, this leads to a lack of order, chaos, and in some cases even tragic results. Possession is one of the most important needs of a human, when it is oppressed like in mass housing, it reaches destructive measures. “it all has to do with the need for a personal environment where one can do as one like”1 - People living in mass housing units might own the property but they do not possess it, because they do not participate in creating them. “The only way in which the population can make its impression on the immense armada of housing block which have got stranded around our city centers is to wear them out. Destruction is the only way left.”2

A closer analogy to mass-produced playgrounds might be today’s development housing projects which try to provide a carefully curated image of a happy lifestyle for an average human, because it is financially driven the emphasis lies in capitalizing on the preferences of the majority, selling a standardized concept to the masses. Instead of creating properties to adapt to an individual’s lifestyle, this kind of projects provide as many formal properties for anyone to adapt to this common image of a “happy life”. “In mass housing the whole society the involvement of the individual is deemed to be undesirable. The general application of this method distinguishes us fundamentally from the way man has built earlier in history. [...] Our ideas of housing reduce him, in essence, to a statistic.”3

Standard Development block

Ideological changes in Georgia do not translate into change of the concept of housing today, both ways statistics are the main driver, development houses concentrated on profit dive into mass-production, they work practically in the same way as soviet mass-housing programs but distributed in many owners and regulated by the market. If being productive in the fastest way was the reason for monotony before, now, in the capitalist regime, it is desired to conform to the average, standard image to maintain value. One thing remains unchanged: “Man no longer houses himself: he is housed.”1

It is important to note that absence of limitations doesn’t lead to more possibilities or broader imagination, certain qualities are essential to provide a solid foundation for creativity. Having infinite possibilities of what one could do, might be the biggest reason one might end up doing nothing. In the case of individual houses and tectonics, Dom-Ino house like reinforced frame structure, especially in Georgia, has emerged as the go-to solution. It seems to have become the default choice, with little variation or alternative options considered when individuals decide to embark on construction projects.

So called “Shavi Karkasi” can be considered as a starting point with no properties, where most of the decisions are considered as user’s preferences, but in reality the user does not know what to do, if there is a possibility of individuality it is based on a collective pattern. The degrees of incentives are so low in basic reinforced frame structures that it becomes itself an agent of homogenization of spaces. Square columns, 5x5meter spans and other default properties result in default decisions. Specific properties set certain things in motion, no specificity at all creates generic architecture. In a way, Shavi Karkasi is over-defined as it is overly neutral

Another potential problem of having no limitations is chaos. Individuals cannot see the whole picture, and an ego-centric approach can be dangerous. It’s crucial to establish basic organizational and quality standards early on to guide design decisions. Architecture also benefits when something remains limited and unchanged—a constant, a reference point for all individual contributions. Without such contrast, it is impossible to identify individual contributions.

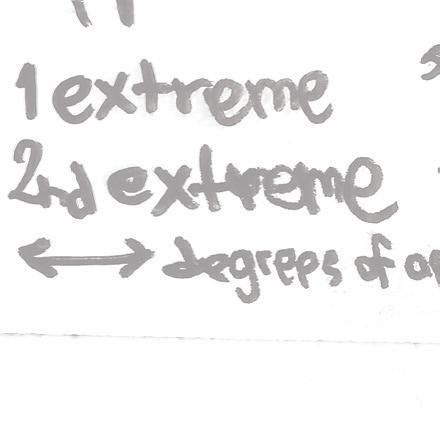

A line of degrees of possible adaptability can be introduced. Mass housing being on one side and individual houses on the other. But buildings positioned closer to the middle are much more important for understanding the goal of balancing order and individuality.

A project worth mentioning is Alejandro Aravena’s Elemental housing. This project provides half built units and a system with platforms and voids that supports potential extension of the units. In this case, I think, the project positions itself not in the middle, but on the both sides of the adaptability line. Its adaptable part is independent from the built part so much that it could be considered as different project set inside the limitations of the provided space. The unchanged, built part of the project is architecture that is already a finished product

Housing for medical faculty students by Lucien Kroll is definitely one of the important references in the middle of line, although it had a high degree of adaptability it was based on a system created by the architect. Instead of relying on a single perfect concept, Kroll used a mix of durable and adaptable structures to anticipate changes The rigid bay structure accommodates traditional rooms, while individual studios are created within the generative column grid. Students freely elaborate on the wooden ‘barns’ located on the roof. Kroll stated that the building was already finished when the load bearing structure was built. The building’s skin, space plan and interior stuff had to be added by the uses themselves. The users’ participation was the most direct way to introduce their wishes into the project. Kroll made several precautions in order to manage the users’ participation in the design of the infill of the load bearing structure. He set up a catalogue of compatible components, modulated the loadbearing structure on a 30cm grid and centralized technical services in accessible distribution points. These measures enabled an endless number of possible plan layouts and allowed Kroll to stay in control at the same time. This project, led by Kroll encourages experimentation rather than imposing a specific way of life

Both architects and users have their limitations, and their exclusive capabilities. Non-architects look at a building from the inside out, they concentrate on their own living spaces, on their own experience and cannot visualize the outcomes of their own interventions in the building as a whole. “The family puts screens on the porch one summer because of the bugs. Then they see they could glass it in and make it part of the house [...] It happens that way because they can always visualize the next stage based on what’s already there.”1 – Stewart Brand quotes an unknown architect in his book “how buildings learn”. But this way every decision is based on the individual lifestyle of the user, every decision is well grounded, and financially viable.

The desire to modify our own houses, comes not only from practical needs, one of the most important reasons is the need of possession, and to possess something individuals have to take actions to “sign” it. (user) does some carpentry, renews a floor, improves the heating, changes the lighting. From this point we can no longer draw a line which denotes the change to an activity we call building. Dwelling is indissolubly connected with building, with forming the protective environment. These two notions cannot be separated, but together comprise the notion man housing himself; dwelling is building 2 This way humans create a sense of belonging. We have a need focus on aspects of our daily lives that directly affect us. By actively effecting to these circumstances, they become meaningful parts of our lives. There is nothing worse than living amidst things that are indifferent to our actions.

An architect can never provide a tailored experience for each and every individual in bigger scale projects or sometimes even individual projects, however, an architect knows what buildings can provide. By helping users visualize possibilities, and creating Frameworks that are neither neutral nor specific there is a solid foundation for creativity. - “…so that it is appropriate for everyone in their own way and in their own words. Architects and architecture accordingly provide the language rather than the narrative and with it the ‘structure’ that can generate ever new narratives from place to place and from moment to moment.”3

Drawings by Donald Ryan (How Buildings Learn)

A useful concept relating to this topic is affordance, coined by James J. Gibson. Best-known definition of this term is from his book, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1979): “The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. ... It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment.”1 Gibson originally described affordance as all the potential actions available in the environment, which can be objectively measured and are independent of an individual’s ability to perceive them. However, the ability to perceive these affordances depends on the capabilities of the organism. For example, a set of stairs with high steps might not afford climbing for a crawling infant. So affordances must be measured along with the relevant actors

It is also important to distinguish affordances from perceived affordances, this distinction was first made by Donald Norman in “The design of Everyday Things” (1999) after admitting he was using the term incorrectly before: he was actually referring to perceived affordance. This distinction makes the concept dependent not only on the physical capabilities of the actor, but their goals, plans, values, beliefs and interests. 2 If an actor steps into a room with an armchair and a softball, Gibson’s definition of affordance allows that the actor may toss the recliner and sit on the softball, because that’s objectively possible. Norman’s definition of perceived affordance captures the likelihood that the actor will sit on the recliner and toss the softball, because of their experience with them in the past.

So if affordances of municipal parks may appear larger in quantity, it is because perceived affordances are more apparent, design of these parks come with a lot of preconceived uses. In my opinion, perceived affordances are a comfort zone for a human, and most of the time humans lean into them without considering all the other affordances. Having a small amount of perceived affordances can be a push for imagination. But it is important not to mix having less perceived affordances with having less affordances. There should be a lot of room for subjective assimilation but less room for preconvieved affordances

Percieved Affordances

“ Architects should not merely demonstrate what is possible, they should also and especially indicate the possibilities that are inherent in the design and within everyone’s reach. It is of the utmost importance to realize that there is a lot to be learned from how occupants respond individually to the suggestions contained in the design.”1

“Therefore, rather than being neutral, form should contain the greatest possible variety of propositions which, without imposing any one specific direction, can thus constantly bring about associotions. An incitement Is necessary to motivate ond stimulate man to adapt his environment to his own needs and to make It his own.”2

Plans and Section

Diagoon Housing (Hertzberger)

“How much one has to do with one’s neighbours depends to a great extent on the type of boundary there is between the gardens. A fence is essentially a means of obtaining maximum isolation from each other. Absence of all boundaries, on the other hand, means being seen constantly by one’s neighbours, being unable to avoid one another. Simply providing the rudiments of a partition between adjacent premises, by woy of on invitation to which everyone can respond as he wishes, provides on incentive ond legitimates the measures which everyone would like to take, but which they would otherwise hesitate to take on their own. A low base of perforated blocks provides the foundation or a brick wall, but it can also serve as the support for a wooden fence.”1

“Window frames are designed in a way as to offer a choice of glass or rather closed panels. As long as it is filled in symmetrically it will always show a characteristic appearance. Probably this architectonic intervention, the way it literally wants to explain the idea of framework (structure) and infill, was pushing too far and did not really work out. Those windows that are not composed after this design principle are added by inhabitants in places of their own choice.”1

“Viewed from the living-room above, the concrete beam marks a space that could, in principle, be turned into on outdoor living space to which access is provided by the ‘window’ · deliberately positioned and proportioned in such a way that, depending on personal interpretation, it can be used either as a Iarge window or as a small door. Garages were not formally provided for in the plan, although this would not have been unusual in this type of housing. But the carport-like space of street level can be used as such, and even garage-doors can quite easily be installed. but this space can equally well be used to creole on extra room: an office, study or workshop which can be mode directly accessible from outside if necessary. So many people leave their ca rs out of doors anyway.”2

Layout options

Some buildings are nobody’s own and some can be very specifically someone’s, like the polar sides of what architect can provide and what user creates, these two kinds of buildings are also extreme opposites, to explore this relationship between an architect and an user we need something in between. Two programs most appropriate and interesting for exploring this relationship between the architect and the user are housing and bazaar/commercial spaces. Looking at the lived experiences of these programs, they already display unplanned unique interventions of users. Users of housing have the strongest investment to be the architect themselves, for them their house is not a building, it is their property, it is a shell for their life. “If people have money to spare, they will mess with their building, at minimum to solve the current set of frustrations with the place” - Stewart Brand.

Occupants of Commercial spaces have a strong interest to be the architect as well, given that a significant portion of their lives unfolds within these spaces and the success of their businesses directly influences their wellbeing. This means architecture of commercial spaces are important for the owner: the ways they are presented to consumers, the ways they adapt and create a productive working environment and a well working system, all of this attributes need their own interpretation and change from owner to owner.

Both of these programs result in chaos, if uncontrolled. Both architect’s and user’s inputs are important and the line between individuality and over-defined architecture should be drawn while exploring these programs, and human relationship with them. Mixing these two programs requires a good amount of architectural interventions to distinguish and explore the relationship between these programs and provide a well working framework. This mixture of building programs also achieves to present different kinds of expressions of individuals in architecture. These programs also suggest several formal goals that will be interesting to explore: Identifying user’s identity to choose the correct framework; maintaining ability to see what it was originally; encouraging as big as possible decisions envisioned through experience.

Nestled along the sidewalk, this Overshadowing Commercial-private Building stands out with its interesting mix of spaces. On the ground floor, you’ll find various shops and commercial spaces where people can cut hair or browse through items for sale. This bustling area creates a lively atmosphere, drawing in passersby and adding to the energy of the street. Above, on the second floor, are private rooms and offices where users can retreat from the hustle and bustle below. Despite being in the heart of the city, these spaces offer a sense of peace and privacy, making them ideal for urban dwellers seeking a balance between city life and relaxation. With its thoughtful design that seamlessly integrates with the sidewalk, this building serves as a vibrant hub where commerce meets community, enhancing the overall character of the neighborhood.

This Neighborhood is mainly used for housing programmes, it could even be described as a quite one. But this particular block is slowly starting to become more alive and active. The foot traffic all around the day is more than other parts of this area, there are a lot of Bazaars nearby and the area is dence enough but not too much. These are some of the perfect properties for an active but also quiet building, which can make the neighborhood noisy during the day, but join in the quiet life during the night. The size and the dimensions of the site are also perfect for a housing/bazaar building.

Context map

Bibliography:

R. De Graaf, Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession (2017)

N.J. Habraken, Supports: an alternative to mass housing (1972)

Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn (1994)

Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture (1991)

H. Hertzberger, Diagoon Housing Delft (1970)

W. Galle, N. de Temmerman, Multiple design approaches to transformable building: Case studies. (2013)

J. J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1979)

D. Norman, The design of Everyday Things (1999)

Student Ilia Osiashvili

Mentor David Giorgadze

Supervisor Jesse Vo gler

VA[A]DS Fre e Universit y of Tbilisi