IAN CHIU

Barcelona with Marianna Godfrey and Joseph L’Heureux

As part of a summer studio in Barcelona, two partners and I designed an intervention in one of Barcelona’s many courtyard gardens. In our site analysis for our selected garden, Jardin de Tres Tombs, we found that the garden was already successful as it was advantageously situated next to a community daycare. The playground, basketball hoop, and ping pong tables were all actively used to the delight of the locals at all times of day that we observed. Therefore, it was important for us to further enhance the experience in the garden without taking away the richness of life already taking place that made us fall in love with the site in the first place.

The only issue we observed in the space was lack of shade, which made some areas unused and prevented parents from having a place to watch their children. We also observed an abandoned car workshop making up the entire southeast façade. We decided planting a grid of trees and carving into the workshop would provide the needed shade, while also expanding the garden’s footprint. From there, we each split off to develop a variation on this central idea. My variation ties the outside of the intervention to the inside with an arch motif, which connects the column grid within the workshop to the branches of the tree grid outside.

Jardin de Tres Tombs features two entrances: one large alley and a smaller tunnel. The intervention seeks to engage both of these, jutting into the path of the large alley with a ramp, while a straight sightline to the back of the workshop all the way through the tunnel pulls people in from that way. The visual interplay of the arches, upside-down arches, and voids provides a playfully shifting architecture as users move through.

Rich Computing Center on Georgia Tech’s campus has sat abandoned after it was no longer needed as a server host. The current design revolves around two large server rooms that now sit empty, and the entire space is largely dark and inhospitable since it was moreso designed for the computers than people. In seeking to expand Georgia Tech’s College of Design, this proposal houses an expansion for the CoD within Rich by converting the two large server rooms into courtyards.

The conversion to courtyards brings in much needed space, light, and air into the previously imposing endless mass of Rich. The courtyards also seek to bring visual connection across their spans, providing a greater sense of connection between a largely isolated and fractured College of Design. One courtyard in the heart of Rich features seating and a stage for performances and convocations, while the other sits empty for more flexible programming. The courtyards continue the language of the College of Design dictated by other pre-existing courtyards throughout the campus in CoD buildings.

After excavating the mass of Rich to create the courtyards, a question rose of how to expand not just the College of Design’s physical space, but its influence on campus.

Spiritually relocating the excavated mass as two pavilions in the “grove” in front of Price-Gilbert Library alongside Rich and the Hinman Research Building activates a currently unused space as a highly visible location within the heart of campus.

One pavilion manifests as wood as it sits above ground amongst the trees while the other forms as concrete because it is embedded into the ground along an existing retaining wall.

Atlanta, Georgia

The musicians’ collective utilizes a fanning motion to tie the axis of the street to that of the BeltLine. This gesture also creates a threshold that pulls users into the building and outdoor terraces that overlook the BeltLine. Folding screen panels along the street and BeltLine facades allow for adjustment of shading and the impression of folding paper. The building thus acts as a giant lantern.

The design allows for both planned and impromptu performances. The outdoor terraces allow music to permeate down to the BeltLine. The central staircase allows sound to echo from the depths of the building to its peak. The primary performance space features a large folding wall that can open up to the BeltLine and entertain visitors passing through on the light rail.

The stereotomic public stair accentuates and draws inspiration from the surrounding site in multiple different ways. Its simple surfaces present a blank canvas for local artists to make their statement on, much as the space under the bridge. There are spots for users to rest and recline both short term alongside the path of the stairs and long term in an area following the curve of the road. Pointed outcrops clearly delineate a space for users to enjoy views, while the presence of trees emphasize where to rest. The form of the stair also takes care to ensure the flow of traffic is not emptied directly onto the BeltLine. There is instead a large plaza once the stair reaches the ground.

Atlanta, Georgia 04|

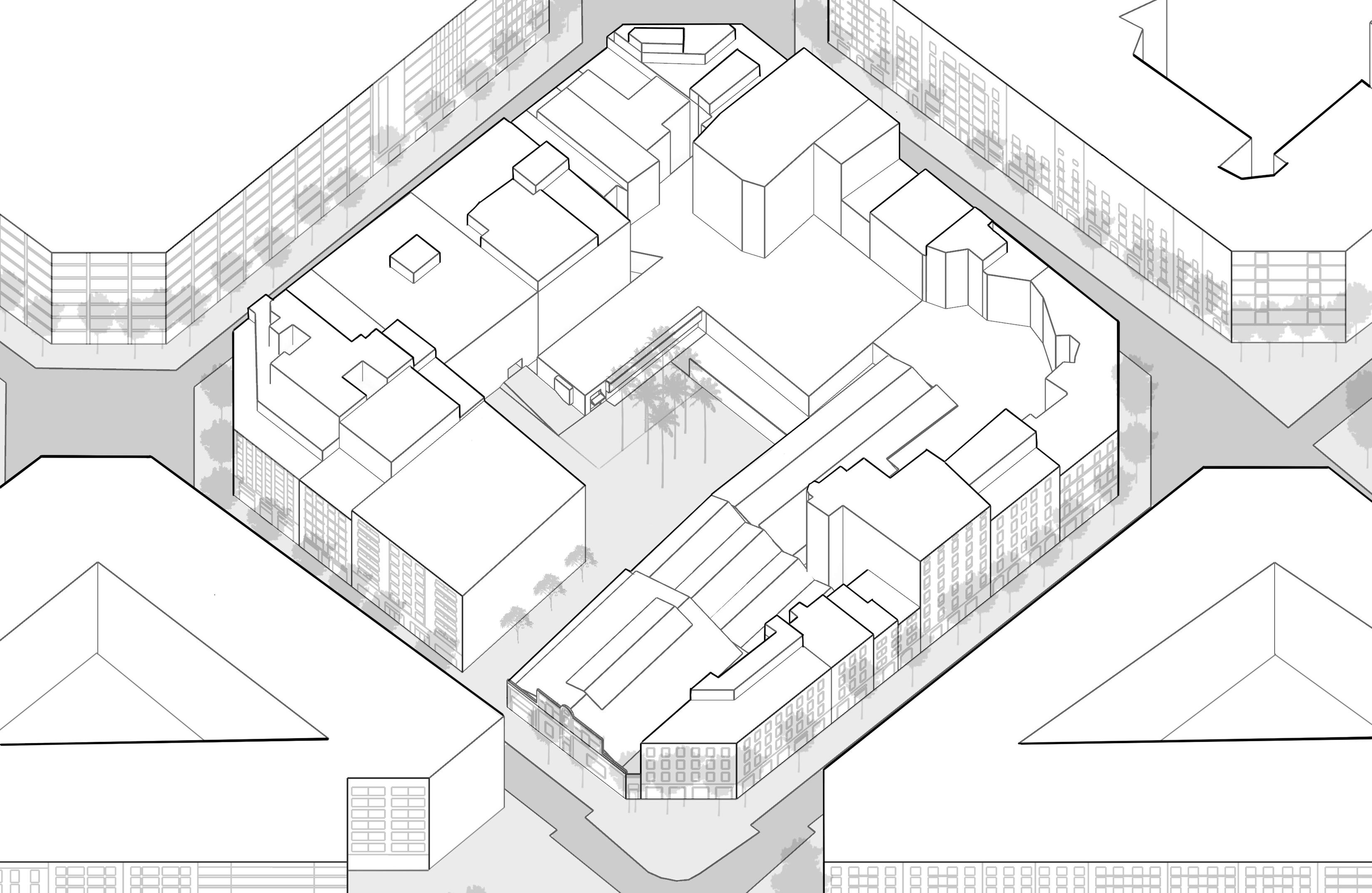

Makerplace is a proposal for a mixed-use affordable housing complex in West End that will sow the existing community with educational opportunities rather than supplant it in the manner of recent gentrified developments. When Whitehall Tavern created a gathering space along a crossroads in 1835, a community sprouted around it that became what is now West End. Makerplace seeks to revitalize West End by recreating this community gathering space in a modern context by housing not only people but both maker and marker space, in a communal environment that will nurture community growth and bonding.

To ensure quality of life for the individual residents of the complex is not lost in pursuit of the larger scale community building, each apartment features both a balcony and a small “front-porch” area where residents could put a seat or plant a small garden. The arrangement of housing expresses three courtyards, which in turn define the non-housing programmatic arrangement. The Culberson Street courtyard, will be exclusive to residents of the complex, and will feature both a pool and a large green lawn, both of which encourage residents to spend time with one another.

An intermediate courtyard features a winding ramp connecting Peeples to Culberson. This monumental ramp encourages residents to adopt it in their daily routine by creating a more direct path from the southern end of Culberson Street to the northern end of Peeples, thus encouraging further engagement with the complex and library.

The crowning jewel of Makerplace is the makerspace, which also serves as a “markerspace” whose openness and color invite engagement and security through visibility. Ease of viewing and access into the makerspace from multiple elevations inspires the curiosity of locals to explore and look closer. The makerspace is accessible from Peeples Street, but is also accessible through the third courtyard. This courtyard serves as an outdoor expansion of the makerspace’s community-building experiences, providing a safe, open area with built-in seating to help host activities such as outdoor reading time, chess club, and local performances. Surrounding the courtyard are indoor meeting spaces that could host seminars or club gatherings. Curvilinear forms distinguish the public programming such as the monumental ramp or the makerspace from the rectilinear apartments or residential courtyard.

Chicago, Illinois with Sarah Davis 05|

This project involved using Gothic-based sheets developed through research to design a club. Given the prevalence of residential, arts, and educational buildings in the site at 645 Wabash Avenue in Chicago, along with the ties the American Deaf community has to the North as the birthplace of American Sign Language, this club became a Deaf culture club.

Through research of the Deaf community, it was clear that the Deaf cherish an uninterrupted visual connection between two individuals. This need for connection was a guiding factor in the design, which is reflected in how almost no rooms have true solid walls and how club users can see through floors, ceilings, and the sheets.

The first phase of this semester long project involved analyzing Gothic tracery and conducting studies of how its component C, S, and J figures can be used to create open nodes, which in turn can compose a large grid that can be further transformed with movements such as subtraction and layering to create a variety of sheets. From the scale of a single figure all the way to the composition of entire sheets together, the transformations create unique voids within.

The Gothic tracery inspired vertical sheets and horizontal beams that make up the structure of the building add a playfulness and intricacy to the construction that can be likened to the hand movements of ASL.

Side facades utilize the untransformed open node grids to tie themselves to the four sheets while still distinguishing themselves from them. Colored glass on the two sheets that make up the exterior facade vary in depth based on proximity to localized symmetries within the sheets.

Galicia, Spain with Emily Mosbaugh and Sophie Myers

Modeling project of Arata Isozaki’s Museo Domus. Involved capturing the rich textural details of Isozaki’s work in both drawing and in rendering.

3inch thick engineered

Milan, Italy

Parametric modeling of the tower portion of Zaha Hadid’s Generali Tower. Involved analysis of 2d and 3d partis, the rotation and scaling as the building increases in height, the system of columns, and the system of the facade.

In addition to modeling the tower as is, variations of the structure were created. Variation 1 features columns that do not form a continuous line throughout the height of the building. Variation 2 features a lower amount of columns that are instead thicker.

Atlanta, Georgia 08|

This design serves as an urban infill project for a site in historic Castleberry Hill. It had to have a live/work space for two artists and exhibition space, which were to have their own circulation, as the exhibition space is not meant specifically for the two artists. Space for an additional 10k massing was also to be set aside.

The main goal of this design is to celebrate craft. In this digital age we only think about finished products, and more of what we have is created by machines rather than by someone’s hands, so the design serves to remind people of the skill of craft. A milliner and a welding artist serve as the two artists because, as a pair, they capture the history of craft. Millinery is thought of as a traditional craft while welding has modern industrial associations.

Nelson St., but can’t be accessed there. The design engages both these sides by splitting into two spaces. To ensure the design functions as one whole and not two separate designs, the final concept is one whole split into two halves that are physically separate, but visually linked. Both follow the site geometry of the brick façade’s angle, while as a contrast the 10k massing does not.

The design creates a timeline from the south façade all the way to Nelson St. Raw materials are brought to the warehouse space by the brick facade. The artists mold these materials into art. Finally, finished art is displayed in the gallery by Nelson St. The 10k massing features an overhang, creating an open space underneath, which allows people in the gallery to see the artists in their studios, tying the two buildings together. The artists become a living exhibit where they can be seen first hand, creating their art. Within the gallery, visitors can view sculptural works from all angles, such as from above through a large skylight. The main stairs wrap around the gallery and feature platforms where people stop to look at the artists.