Special Issue: COVID-19: Education Response to a Pandemic

Volume 9 – Issue 2 – 2021

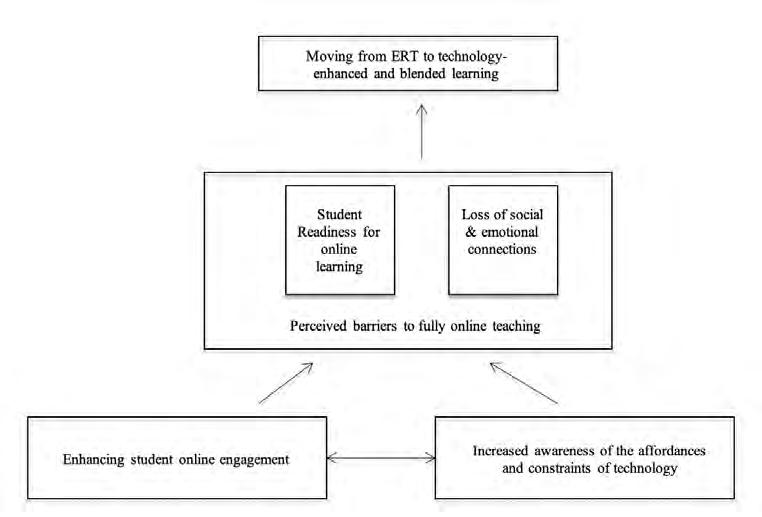

synchronous communication platform, and two were conducted via email due to technical or personal issues related to participants. Email responses and Zoom interview transcriptions served as the raw data in this study. Email interviews were conducted in two phases, in which interview questions were sent to participants and their answers were returned, followed by probing questions from the researcher for clarifications or to elicit richer responses to support a deeper exploration of the personal experiences being discussed (Smith, 2004). Results The analysis highlighted three common themes: enhancing student online engagement; increased awareness of technology affordances and constraints; and moving from ERT to technology-enhanced and blended learning. In this section, these themes are explored and supported with representative quotations from faculty interviews. Enhancing Student Online Engagement A common challenge among all participants was ensuring students’ active engagement with instructor, peers, and course material. All participants discussed ways in which they tailored activities/assignments and teaching strategies to encourage student engagement in this new learning environment. Take Helen for example, The main issue faced in moving online was developing a medium that allowed students to talk between themselves, as they would in a class, and not for all communication to be lecturer to student, but also that we managed to succeed in facilitating student-to-student communication as well. When first required to shift online, Nora continued to implement her existing f2f plans with no changes; however, she noticed a decrease in student engagement and interaction. Within a week of the shift to ERT she realized that she could not simply map the three hours she normally provides in class to the virtual space because it is a completely different environment. She recognized that online environments requires different types of incentives for students to participate and engage with peers and course material. As a result, she worked on changing some of the learning material and pedagogical use of technology tools, such as discussion boards, to increase student engagement with course topics. For instance, instead of using the discussion board for discussions and debates as she did prior to the pandemic, she began to use it for student reflection to encourage a deeper cognitive engagement. Helen, Susan, Nora, and Sara discussed their students’ preference for text-based interaction versus audio/video during live sessions. For Helen, this preference was a challenge. She explained, the ‘teaching’ was challenging, at least to me; I like to see the whites of students’ eyes. Similarly, when Susan was asked about the most challenging aspect of remote teaching, she replied, The inability to understand the extent of student understanding. When repeatedly asked, ‘Is anything unclear?’ very few students used to respond. Susan found it difficult to assess student understanding of topics discussed during live sessions due to students’ reluctance to ask questions, compounded by the lack of eye contact that would allow her to gauge students’ reactions and facial expression. So, instead of asking students if they had any questions, she began by asking course-related questions throughout the live sessions and encouraged students to respond via the chat facility, a strategy she found to be very effective as the chat facility was very active in all my classes.

13