Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms.

Printed in the USA A-Print

Module Summary 2 Essential Question 3

Suggested Student Understandings 3 Texts 3

Module Learning Goals 5 Module in Context ............................................................................................................................... ........................ 7 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 8 Major Assessments 9 Module Map 12

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–11 How and why does language inspire?

Lesson 1 ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 25

n TEXT: “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Inspire Lesson 2 37

n TEXT: “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Winsome

Lesson 3 49

n TEXTS: “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay • “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson • “Kinetic Poetry Hope Is the Thing with Feathers,” Nook Harquail, director

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Argument, claim Lesson 4 61

n TEXTS: “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson • “Dreams,” Langston Hughes • “Dreams,” Langston Hughes (audio)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Precision and Concision

Lesson 5 73

n TEXTS: “Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou • “Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou (video)

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: The Suffix –dom

Lesson 6 83

n TEXTS: “Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou • “Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou (video)

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Figurative language

Lesson 7 93

n TEXTS: Inaugural Address, John F. Kennedy (excerpt) • Inaugural Address, John F. Kennedy (video) • “‘Ask Not … ’: JFK’s Words Still Inspire 50 Years Later,” Nathan Rott • “Dreams,” Langston Hughes • “Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou

¢

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Repetition in Writing

Lesson 8 105

n TEXTS: Inaugural Address, John F. Kennedy • Address to the United Nations Youth Assembly, Malala Yousafzai • “Thanks to Malala: Top 3 Ways Malala Has Changed the World,” Alex Harris

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Precise Language

Lesson 9 117

n TEXTS: “I Have a Dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. • “I Have a Dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. (video) • “Is Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ the Greatest Speech in History?” Emma Mason

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Concision

Lesson 10 127

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute with Precise and Concise Language

Lesson 11 ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 135

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Alternate claim, opposing claim

Focusing Question: Lessons 12–21

How and why does language persuade?

Lesson 12 145

n TEXTS: “Serena Williams—Rise,” Andre Stringer • Advertisements

¢

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Persuade, persuasive Lesson 13 159

n TEXT: “How Advertising Targets Our Children,” Perri Klass

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Manipulative, deceptive Lesson 14 ............................................................................................................................... ................................... 169

n TEXTS: “How Advertising Targets Our Children,” Perri Klass • “Serena Williams—Rise,” Andre Stringer • Advertisements

¢

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 15 179

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter I

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Phrases

Lesson 16 193

n TEXTS: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter I • Excerpts from “Friedrich Engels, Revolutionary, Activist, Unionist, and Social Investigator,” Rosalie Baker

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Clauses

Lesson 17 207

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter I

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 18 219

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter II • Excerpts from “Friedrich Engels, Revolutionary, Activist, Unionist, and Social Investigator,” Rosalie Baker

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Commandment

Lesson 19 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 233

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter III

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Maxim

Lesson 20 245

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapters IV–V

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 1 Lesson 21 255

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapters I–V

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Phrases and Clauses

Focusing Question: Lessons 22–30

How and why is language dangerous?

Lesson 22............................................................................................................................... .................................. 265

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter VI

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Scapegoat

Lesson 23 279

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapters VI–VII

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Varied Sentence Structures

Lesson 24 295

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter VIII

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Complex Sentences Lesson 25 307

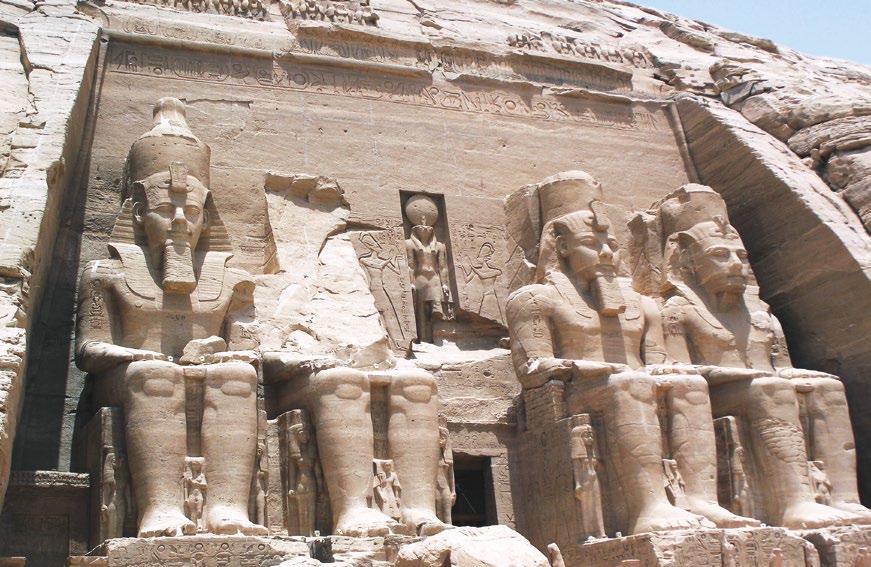

n TEXTS: The Temple at Abu Simbel • The Great Sphinx of Giza • Excerpts from “Grandeur at Abu Simbel,” Steven Snape • Excerpts from “Let’s Tour the Temple,” Ramadan B. Hussein

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Cult of personality

Lesson 26 319

n TEXTS: Mini BIO—Joseph Stalin (video) • Propaganda Posters • Animal Farm, George Orwell

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Allegory

Lesson 27 331

n TEXTS: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter IX • “First They Came for the Communists,” Martin Niemoller ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Complex Sentences in an Argument

Lesson 28 341

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell, Chapter X

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Simple Sentences in an Argument Lesson 29 355

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Orwellian Lesson 30 365

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Varied Sentence Structures in an Argument

How and why does language influence thought and action?

Lesson 31 375

n TEXTS: “In 1946, the New Republic Panned George Orwell’s Animal Farm,” George Soule • Review of Animal Farm, Michael Berry • Review of Animal Farm, Bapalapa2, student reviewer

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Satire Lesson 32 385

n TEXT: “Why You Should Read Animal Farm,” Kainzow, blogger

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: The Morphemes lit, litera Lesson 33 ............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 395

n TEXT: Animal Farm, George Orwell Lesson 34 401

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 2 Lesson 35 409

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

Lesson 36 415

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel at Peer Editing Lesson 37 423

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Review

Appendix A: Text Complexity 431

Appendix B: Vocabulary 433

Appendix C: Answer Keys, Rubrics, and Sample Responses 441

Appendix D: Volume of Reading 459

Appendix E: Works Cited 461

It is a paradox that every dictator has climbed to power on the ladder of free speech. Immediately on attaining power each dictator has suppressed all free speech except his own.

—Herbert HooverWhat is the power of language? Poets understand words’ power to inspire, advertisers understand words’ power to persuade, propagandists understand words’ power to manipulate, and leaders understand words’ power to sway the course of human events. In every facet of our lives, as we navigate an onslaught of information from myriad sources, we experience the power of language in personal, political, commercial, and civic arenas.

Those who fail to realize language’s power are powerless themselves. The dictatorial society depicted in George Orwell’s Animal Farm becomes inevitable only when citizens surrender their commitment to critical literacy and thoughtful participation in government. Young people today have greater access to information than at any time in history, but they must be able to evaluate its validity, ask questions that will help them differentiate truth from falsehood, and stand up for their carefully considered beliefs.

Module 3 cultivates students’ abilities to analyze the logic and validity of arguments; to consider the perspectives of differing sources; to hold thoughtful, respectful discussions with others holding conflicting points of view; and to recognize language’s potential for both inspiration and manipulation. The texts compel a deep examination of rhetorical and propaganda techniques and appeals to logos, pathos, and ethos. Through this study, students learn to identify these techniques when they encounter them and employ appropriate and logical reasoning in their own compelling arguments. Ultimately, students build an understanding of the need to develop the critical reading and thinking skills that will enable them to recognize when others attempt to persuade or manipulate them with language.

At the core of the module, Animal Farm, Orwell’s classic indictment of tyranny and corruption, provides a foundation for these lessons. However, because Orwell’s vision of language, class, and society is nearly as bleak as it is profound, poetry and speeches offer a vital, complementarily uplifting perspective. Alongside Orwell’s whip-wielding pigs, students meet metaphorical birds who croon songs of hope, politicians who call citizens to help those less fortunate, and activists who spread human rights and freedom, illustrating language’s power to spark positive change. Taken together, Animal Farm and the supplementary texts enable a study honoring the multifaceted yet inextricable relationship between language and power.

By the time students encounter the End-of-Module (EOM) Task, they know language is powerful. But, is language more powerful when used to uplift or to control? Students weigh evidence from the array of texts and craft their own argument in response.

Words carry power to inspire, uplift, persuade, manipulate, and control.

Language is a powerful tool for those seeking power or influence.

Failing to read and think critically about political content, media messages, and advertising can be dangerous.

Writers and speakers can use many techniques to inspire, persuade, control, and argue a point.

Photograph of Abu Simbel, Wikimedia Commons (http://witeng.link/0293)

The Great Sphinx, Encyclopædia Britannica Online (http://witeng.link/0295)

The Lincoln Memorial, National Park Service (http://witeng.link/0296)

“‘Ask Not … ’: JFK’s Words Still Inspire 50 Years Later,” Nathan Rott (http://witeng.link/0276)

“How Advertising Targets Our Children,” Perri Klass (http://witeng.link/0353)

“Is Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ the Greatest Speech in History?” Emma Mason (http://witeng.link/0286)

“Thanks to Malala: Top 3 Ways Malala Has Changed the World,” Alex Harris (http://witeng.link/0283)

“In 1946, the New Republic Panned George Orwell’s Animal Farm,” George Soule (http://witeng.link/0306)

Review of Animal Farm, Michael Berry (http://witeng.link/0307)

Review of Animal Farm, Bapalapa2, student reviewer (http://witeng.link/0308)

“Why You Should Read Animal Farm,” Kainzow, blogger (http://witeng.link/0309)

Excerpts from “Friedrich Engels, Revolutionary, Activist, Unionist, and Social Investigator,” Rosalie Baker (Handout 16B)

Excerpts from “Grandeur at Abu Simbel,” Steven Snape (Handout 25A)

Excerpts from “Let’s Tour the Temple,” Ramadan B. Hussein (Handout 25A)

“‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay (http://witeng.link/0314)

“Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou (http://witeng.link/0277)

“Dreams,” Langston Hughes (http://witeng.link/0292)

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson (http://witeng.link/0316)

“First They Came for the Communists,” Martin Niemoller (http://witeng.link/0303)

Poetry 180, Library of Congress (http://witeng.link/0321)

Images of Pro-Stalin Propaganda (http://witeng.link/0298)

“I Have a Dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. (http://witeng.link/0284)

Inaugural Address, John F. Kennedy (http://witeng.link/0313)

Address to the United Nations Youth Assembly, Malala Yousafzai (http://witeng.link/Malala-Yousafzai’s-speech-at-the-United-Nations)

“Caged Bird,” Maya Angelou (http://witeng.link/0278)

“Dreams,” Langston Hughes (http://witeng.link/0318)

“Kinetic Poetry Hope Is the Thing with Feathers,” Nook Harquail, director (http://witeng.link/0317)

“I Have a Dream,” Martin Luther King Jr. (http://witeng.link/0285)

Address to the United Nations Youth Assembly, Malala Yousafzai (http://witeng.link/0282)

Mini BIO—Joseph Stalin (http://witeng.link/0297)

Name and describe ways that language and words inspire, persuade, and control.

Describe the structures and techniques used in poetry and political speeches, both in terms of their written expression and oral delivery.

Analyze, contextualize, and critique George Orwell’s Animal Farm to identify and evaluate its themes.

Define and classify elements and examples of propaganda, argument, and persuasion; isolate varied persuasive techniques; and recognize appeals to pathos, logos, and ethos.

Recognize Animal Farm as an allegory, connecting it to the Russian Revolution and the rise of Stalin.

Analyze how the form or structure of a poem, as well as its rhymes and other repetitions of sounds, impact its meaning (RL.7.4, RL.7.5).

Analyze how an author develops and contrasts the points of view of different characters (RL.7.6).

Compare and contrast a text with its audio or video presentation, analyzing each medium’s portrayal of the subject and unique techniques (RL.7.7, RI.7.7).

Trace and evaluate a written argument, assessing the soundness of the reasoning and relevance and sufficiency of the claim (both to evaluate written arguments for their validity and to study models of arguments as preparation for drafting their own written arguments) (RI.7.8).

Formulate sound argument paragraphs to support claims with logical reasons and relevant evidence from Animal Farm and supplementary texts (W.7.1).

Develop and revise an essay presenting an argument about whether language is more powerful when used to uplift or to control, acknowledging alternate or opposing claims and providing a conclusion that supports the argument (W.7.1).

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience (W.7.4).

Pose questions that elicit elaboration from others in discussions about language and power, and then listen for on- and off-topic responses (SL.7.1.a, SL.7.1.c).

Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence (SL.7.3).

Purposefully use simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to signal differing relationships among ideas and help develop and pace argument writing (L.7.1.b).

Choose language carefully, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy, to express arguments precisely and concisely (L.7.3.a).

Determine the meaning of target vocabulary through context, by applying understanding of grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots, and by exploring related words’ connotations and denotations (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b, L.7.5.c).

Interpret figurative language, such as similes, metaphors, imagery, personification, and allusion, and use figurative language in writing in order to be precise, concise, and descriptive (L.7.5.a).

Knowledge: This study builds on Modules 1 and 2 as students continue to explore different facets of human experience in societal contexts. In Module 1, students read stories of individuals developing their identities in the context of the rigidly hierarchical medieval society. In Module 2, students examined the experience of individuals in the context of World War II. In Module 3, the focus shifts from the individual experience to the idea of humanity in society and the power of words to influence our thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Reading: Students deepen the close and analytical reading skills they developed in prior modules by analyzing the techniques writers use, through their written words, as well as oral and video presentations, to inspire, uplift, persuade, manipulate, or control their audiences. This exploration encompasses a broad variety of texts, including poems, speeches, advertisements, and arguments. In studying the core text, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, students identify similar uses of language by the novel’s characters, and they analyze how Orwell develops the characters’ perspectives to identify the novel’s powerful themes about language, power, and the rise of dictatorships. Students also consider the novel’s allegorical meaning as they compare its plot developments with the real-life events that it is based on—the Soviet revolution and the rise of Stalinism.

Writing: Students build on the descriptive and figurative writing they learned while practicing narrative writing in Module 1, and they continue experimenting with narrative writing techniques to inspire readers. The structures and techniques students developed with informative writing in Module 2 serve as foundational building blocks for writing effective arguments in Module 3.

Speaking and Listening: Students extend their speaking and listening skills in three Socratic Seminars about Animal Farm and the supplementary texts by asking for elaboration on key points, listening for off-topic responses, and evaluating arguments.

RL.7.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of rhymes and other repetitions of sounds (e.g., alliteration) on a specific verse or stanza of a poem or section of a story or drama.

RL.7.5 Analyze how a drama’s or poem’s form or structure (e.g., soliloquy, sonnet) contributes to its meaning.

RL.7.6 Analyze how an author develops and contrasts the points of view of different characters or narrators in a text.

RL.7.7 Compare and contrast a written story, drama, or poem to its audio, filmed, staged, or multimedia version, analyzing the effects of techniques unique to each medium (e.g., lighting, sound, color, or camera focus and angles in a film).

RI.7.7 Compare and contrast a text to an audio, video, or multimedia version of the text, analyzing each medium’s portrayal of the subject (e.g., how the delivery of a speech affects the impact of the words).

RI.7.8 Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to support the claims.

W.7.1 Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence.

W.7.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

L.7.1.b Choose among simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to signal differing relationships among ideas.

L.7.3.a Choose language that expresses ideas precisely and concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy.

L.7.4.a Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence or paragraph; a word’s position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

L.7.4.b Use common, grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (e.g., belligerent, bellicose, rebel).

L.7.5.a Interpret figures of speech (e.g., literary, biblical, and mythological allusions) in context.

L.7.5.c Distinguish among the connotations (associations) of words with similar denotations (definitions) (e.g., refined, respectful, polite, diplomatic, condescending).

SL.7.1.a Come to discussions prepared, having read or researched material under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evidence on the topic, text, or issue to probe and reflect on ideas under discussion.

SL.7.1.c Pose questions that elicit elaboration and respond to others’ questions and comments with relevant observations and ideas that bring the discussion back on topic as needed.

SL.7.3 Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

RL.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

RI.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

L.7.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

1. Write a paragraph about why “I Have a Dream” is inspiring, explaining both the contribution of King’s written words in the transcript and the contribution of his vocal delivery and image details in the video.

Demonstrate understanding of how and why language inspires.

Analyze the impact of a speech’s language.

RI.7.1, RI.7.7, W.7.9

2. Write an argument paragraph about which of the three animals Squealer, Boxer, or the sheep is most influential in helping Napoleon gain and maintain power in Animal Farm

3. Write an argument paragraph about the most important theme about the power of language that Orwell develops in Animal Farm

Demonstrate understanding of how and why language persuades.

Analyze how use of language allows Napoleon control the animals in Animal Farm.

Compose an argument with a claim, reasons, evidence, and elaboration.

RL.7.1, W.7.1, W.7.4, L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a

Demonstrate understanding of the role of language in Animal Farm, analyzing how Orwell develops a theme.

Compose an argument with a claim, reasons, evidence, and elaboration.

Acknowledge an alternate or opposing claim.

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, W.7.1, W.7.4, W.7.9.a, L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a

1. Read Maya Angelou’s “Caged Bird,” and view its video performance. Use a graphic organizer to analyze how two techniques in the video affect the poem, and respond to multiplechoice questions.

2. Read the beginning of Animal Farm, chapter V, pages 45–48. Respond to multiple-choice and short-response questions to explain how Orwell develops the contrasting perspectives of the animals, particularly Mollie, Clover, Snowball, and Napoleon.

3. Read the Animal Farm review, and complete the multiple-choice questions. Then trace and evaluate the review’s argument using the graphic organizer.

Analyze how a poem uses language to inspire. Analyze the impact of particular language techniques.

RL.7.1, RL.7.4, RL.7.5, RL.7.7, W.7.10, L.7.4.a, L.7.5.a, L.7.5.c

Analyze Animal Farm citizens’ perspectives on their society, leadership, language, and power.

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.4, RL.7.6, W.7.10, L.7.4.b

Demonstrate understanding of the elements of a strong argument. RI.7.1, RI.7.4, RI.7.8, W.7.10, L.7.4.a

1. Discuss which of the texts is most inspiring, and why.

2. Discuss whether it is the responsibility of a government or its citizens to make sure citizens get accurate, logical information.

Demonstrate an understanding of how and why language inspires in speeches and poems. Determine which texts include the strongest evidence supporting language’s uplifting effect.

Formulate opinions about language and power, supporting ideas with evidence from Animal Farm.

RL.7.1, RI.7.1, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

RL.7.1, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

3. Discuss whether language is more powerful when used to uplift or to control.

Reflect on the relationship between language and power, responding to classmates’ EOM Task arguments.

RL.7.1, RI.7.1, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

Write an argument essay about whether language is more powerful when it is used to uplift or whether it is more powerful when used to control. Develop your argument with evidence from Animal Farm and at least one other text.

Write an engaging introductory paragraph in which you clearly state a claim as to which use of language is most powerful.

RL.7.1, RI.7.1, W.7.1, W.7.4, L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a

Give two reasons for why this use of language is most powerful.

Support your reasons with textual evidence and elaboration.

Acknowledge alternate or opposing claims.

Include a conclusion that reinforces the argument and supports its significance.

Use a variety of sentence structures effectively to express ideas.

Use words, phrases, and clauses as transitions to create cohesion and clarify the relationships among claims, reasons, evidence, and elaboration.

Maintain a formal style featuring precise language and content-area vocabulary.

Demonstrate understanding of academic, text-critical, and domain-specific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms.

L.7.4.b L.7.6

Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

*While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

Focusing Question 1: How and why does language inspire?

1 “ ‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter)”

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about “B”?

Experiment

How do figurative language and sensory language work?

Formulate questions and observations about “B” (RL.7.1).

Experiment with figurative and sensory language inspired by “B” (W.7.3.d).

Develop a clear understanding of the word inspire based on its Latin root and dictionary definition (L.7.4.b).

2 “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter)”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of language and performance techniques reveal in “B”?

3 “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter)”

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers”

Organize

What is happening in “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” and its video version?

Examine

Why is writing a clear claim to introduce an argument important?

Analyze how Kay uses language to inspire her audience (RL.7.4).

Identify and analyze the performance techniques Kay uses to enhance “B” (RL.7.7).

Analyze Kay’s use of the word winsome based on its context and morphemes (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Analyze an argument paragraph about figurative language to understand the characteristics of a strong claim (W.7.1.a).

Interpret “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” and its video version, attending to language and structure (RL.7.4, RL.7.5, RL.7.7).

Deepen understanding of the words argument and claim by comparing and contrasting their use in academic and other settings (L.7.4, L.7.5.b).

4 “Dreams” (text and audio)

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” and “Dreams” reveal?

Experiment

How do claims work? Examine

Why are precision and concision important?

Compare “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” to “Dreams,” analyzing language and structure (RL.7.4, RL.7.2, RL.7.5, L.7.5.a).

Establish a claim about whether Dickinson or Hughes uses metaphor to inspire more effectively.

5 NR “Caged Bird” (text and video) Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of “Caged Bird” and its video performance reveal?

6 “Caged Bird” (text and video) Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of “Caged Bird” reveal?

Define and evaluate the impact of precision and concision in poetry (L.7.3.a).

Analyze how Angelou uses figurative language, structure, and rhyme in “Caged Bird” (RL.7.1, RL.7.4, RL.7.5, RL.7.7, W.7.10, L.7.4.a, L.7.5.a, L.7.5.c).

Integrate understanding about the suffix –dom to define words (L.7.4.b).

Analyze how Angelou uses language to inspire her audience (RL.7.4).

Fluently recite poetry using delivery techniques.

Analyze figurative language in the context of student-selected poems (L.7.5.a).

7 Inaugural Address (text and video)

“‘Ask Not … ’:

JFK’s Words Still Inspire 50 Years Later”

Organize

What is happening in the text and video versions of JFK’s inaugural address?

Examine

Why is supporting a claim with clear reasons and evidence important? Examine Why is understanding the difference between repetition for effect and redundancy important?

Summarize the central ideas in Kennedy’s inaugural address (RI.7.2).

Identify the reasons and evidence supporting an article’s claim (RI.7.8).

Understand the importance of eliminating redundancy while still using repetition for effect as appropriate (L.7.3.a).

8 Address to the United Nations Youth Assembly (text and video)

“Thanks to Malala: Top 3 Ways Malala Has Changed the World”

9 “I Have a Dream”

“Is Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ the Greatest Speech in History?”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Malala Yousafzai’s speech transcript and video reveal?

Examine

Why is supporting a claim with relevant evidence important? Experiment

How does precise word choice in a claim work?

Contrast Yousafzai’s speech transcript to the video to analyze the techniques she uses to inspire her audience (RI.7.7).

Explain the role of relevant evidence in an article about Yousafzai’s impact (RI.7.8, W.7.10).

Employ precise word choice in revising a claim (L.7.3.a).

What does a deeper exploration of King’s language in “I Have a Dream” reveal?

10 FQT All Module Texts Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of “I Have a Dream” and its video reveal?

Experiment

How does concise language work?

Analyze King’s use of language in “I Have a Dream” (RI.7.4).

Choose language to express ideas concisely and to avoid wordiness and redundancy (L.7.3.a).

Experiment

How does relevant evidence work? Execute

How do I use language precisely and concisely and avoid wordiness and redundancy in my writing?

Compare and contrast the transcript of “I Have a Dream” to its video, analyzing each medium’s portrayal (RI.7.1, RI.7.2, RI.7.7, W.7.2, W.7.9.b).

Gather relevant evidence and evaluate the techniques writers use to inspire (RL.7.1, RI.7.1).

11 SS

All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how and why language inspires?

Experiment

How do claims, clear reasons, and relevant evidence work?

Revise writing to express ideas precisely and concisely, eliminating wordiness and redundancy (L.7.3.a).

Engage in a collaborative conversation about how and why language inspires, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Draft an argument featuring a claim, reason, and evidence (W.7.1.a, W.7.1.b).

Use predicted and dictionary definitions of words and word relationships to understand alternate claims and opposing claims, developing basic argumentation skills (L.7.4.d, L.7.5.b).

12 “Serena Williams Rise”

Car Ad 1 Car Ad 2 Dessert Ad Soda Ad 1 Soda Ad 2

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about advertisements?

13 “How Advertising Targets Our Children”

Organize What is happening in the article “How Advertising Targets Our Children”?

Examine

Why is audience awareness important in argument writing? Examine

Why is asking for elaboration important in academic conversations?

14 “How Advertising Targets Our Children”

“Serena Williams Rise”

Car Ad 1 Car Ad 2 Dessert Ad Soda Ad 1 Soda Ad 2

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of persuasive techniques reveal in the advertisements?

Examine

Why are phrases and clauses important?

Formulate observations and questions about video and print advertisements to understand how advertisers try to persuade consumers (RI.7.1).

Deepen understanding of the meanings of the words persuade and persuasive by comparing and contrasting their meanings with those of related words (L.7.5.b).

Summarize the key points the author of an op-ed article makes about the effects of advertising on children (RI.7.8).

Deepen understanding of the words manipulative and deceptive by comparing and contrasting their meanings and using them in context (L.7.5.b).

Analyze the argument of an article to determine its claim(s), reason(s), and evidence (RI.7.8).

Identify phrases and clauses, and explain their function in specific instances (L.7.1.a).

15 Animal Farm, Chapter I Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about chapter I of Animal Farm?

Experiment

How does writing a claim supported by clear reasons and relevant evidence work?

Experiment

How does using phrases in arguments work?

16 Animal Farm, Chapter I

Excerpts from “Friedrich Engels, Revolutionary, Activist, Unionist, and Social Investigator”

Organize

What is happening in chapter I of Animal Farm?

Examine

Why are elaboration and transitions important in argument writing?

Experiment How does using clauses in arguments work?

Assert a claim about whether an advertisement uses fair or unfair techniques to persuade consumers, and support that claim with reasons and evidence (W.7.1.a, W.7.1.b).

Formulate observations and questions about chapter I of Animal Farm (RL.7.1).

Revise an argument paragraph by using phrases to create transitions, add detail and precision, and clarify relationships (L.7.1.a).

Describe key characters introduced in chapter I, identifying specific words, phrases, and actions Orwell uses to develop each character (RL.7.3).

Analyze how Old Major develops an argument in his speech (RI.7.8).

Write an argument paragraph about Old Major’s speech, using clauses to create transitions and clarify relationships (L.7.1.a).

17 Animal Farm, Chapter I Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Old Major’s argument and use of persuasive techniques reveal in chapter I of Animal Farm?

Experiment

How does asking for elaboration in academic conversations work? Experiment

How does elaboration in argument writing work?

Experiment

How does using phrases and clauses in an argument work?

Analyze the argument Old Major makes in his speech and song (RI.7.8).

Compare Old Major’s perspective of life on the farm with that of Mr. Jones (RL.7.6).

Revise argument paragraphs by using phrases or clauses to create transitions, add detail or precision, or clarify relationships (L.7.1.a).

18 Animal Farm, Chapter II

Excerpt from “Friedrich Engels, Revolutionary, Activist, Unionist, and Social Investigator”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character and perspective reveal in chapter II of Animal Farm?

19 Animal Farm, Chapter III Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of language and persuasion reveal in chapter III of Animal Farm?

Examine

Why are logical reasoning and accurate, relevant evidence important to making a strong argument?

20 NR VOC

Animal Farm, Chapters IV—V Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character and perspective reveal in chapters IV and V of Animal Farm?

Describe key character details and developments in chapter II, identifying words, phrases, and actions Orwell uses to develop each character (RL.7.3).

Analyze the contrasting perspectives of the animals in Animal Farm (RL.7.2, RL.7.6, W.7.9).

Deepen understanding of the word commandment by distinguishing among the connotations of similar words (L.7.5.c).

Analyze how Orwell develops and contrasts the perspectives of Napoleon and Snowball (RL.7.6).

Trace and evaluate Squealer’s milk-and-apples argument, assessing his reasoning and use of evidence (RI.7.8).

Use context to determine the meaning of maxim and deepen understanding of the word by comparing it to motto (L.7.4.a, L.7.5.b).

Summarize the opening of Animal Farm, chapter V, and analyze how Orwell develops the animals’ contrasting perspectives (RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.4, RL.7.6, W.7.10, L.7.4.b).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary and how to use affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of words or phrases (L.7.4.b, L.7.6).

Focusing Question 2: How and why does language persuade?

Focusing Question 2: How and why does language persuade?

21

FQT Animal Farm, Chapters I–V Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character and perspective reveal in the first half of Animal Farm?

Execute

How can I use a strong claim, clear reasons, and relevant evidence in an argument paragraph?

Execute

How do I use phrases and clauses in an argument?

Write an argument paragraph, establishing and supporting a claim about whether Squealer, Boxer, or the sheep are most influential in supporting Napoleon’s efforts to gain and maintain power (RL.7.1, W.7.1, W.7.4, L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a).

Revise Focusing Question Task 2 paragraphs by adding phrases or clauses to create transitions, add detail or precision, or clarify the relationships among the claim, reasons, and evidence (L.7.1.a).

22 Animal Farm, Chapter VI Organize

What is happening in chapter VI of Animal Farm?

Excel

How do I improve an argument paragraph?

Evaluate Focusing Question Task 2 response to identify areas for improvement and strengthen the argument (W.7.1, W.7.4, W.7.5).

Analyze the events of chapter VI from the perspective of different characters (RL.7.6).

Apply understanding of literary allusions to interpret the word scapegoat in context as it is used to describe Snowball (L.7.5.a).

Focusing Question 3: How and why is language dangerous? LESSON TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS23 Animal Farm, Chapters VI–VII Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Squealer’s arguments reveal?

Experiment

How does acknowledging alternate or opposing claims work?

Examine

Why is using varied sentence structures important when writing an argument?

Trace the techniques Squealer uses in his arguments about pigs sleeping in beds and about “Beasts of England,” and draft a written assessment of the soundness of his reasoning (RI.7.8).

Draft one or two additional sentences for the Focusing Question Task 2 response to acknowledge alternate or opposing claims (W.7.1.a).

24 Animal Farm, Chapter VIII Distill

What is the essential meaning of Animal Farm?

Experiment

How do complex sentences work?

Identify and evaluate the impact of varied sentence structures (L.7.1.b).

Identify and analyze a theme that Orwell develops in Animal Farm (RL.7.2).

25 The Temple at Abu Simbel

The Great Sphinx of Giza

Excerpts from “Grandeur at Abu Simbel” and “Let’s Tour the Temple”

26 Animal Farm “Communism”

“Mini BIO— Joseph Stalin”

Images of Pro-Stalin Propaganda

Know

How do the temples at Abu Simbel and the Great Sphinx at Giza build my knowledge of monuments of ancient Egypt and how those connect to central ideas in Animal Farm?

Combine simple sentences to create complex sentences to communicate multiple ideas (L.7.1.b).

Formulate observations and knowledge about selected monuments of ancient Egypt, and connect these to the ideas in Animal Farm (RL.7.2, SL.7.2, W.7.10, L.7.6).

Deepen understanding of the phrase cult of personality, in part by distinguishing among the denotations and connotations of words related to cult and personality (L.7.5.c).

Organize

What’s really happening in Animal Farm?

Examine

Why is the structure of an argument essay important?

Identify parallels between Stalin in the Soviet Union and Napoleon in Animal Farm (RI.7.2, RL.7.2, SL.7.2).

Demonstrate understanding of and accurately use the literary term allegory (L.7.5.a).

27 Animal Farm, Chapter IX

“First They Came for the Communists”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of theme reveal in Animal Farm?

Experiment

How do complex sentences work in an argument?

Identify signs of the growing class divide on the farm, and analyze the ways that the pigs use language to obscure inequalities (RL.7.2).

28 Animal Farm, Chapter X Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the dramatic conclusion reveal in Animal Farm?

Examine

Why are introductions and conclusions important? Experiment

How do simple sentences work in an argument?

Write complex sentences to present a claim, and contrast it with an alternate or opposing claim (L.7.1.b).

Describe a theme revealed in the final chapter of Animal Farm (RL.7.2, W.7.10).

Write simple sentences to clearly and concisely state a claim or conclude an idea (L.7.1.b).

29 SS Animal Farm Distill

What is the essential meaning of Animal Farm?

Engage in a collaborative conversation about Animal Farm and the power of language, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Describe a theme on language and power that Orwell conveys in Animal Farm, and provide a textual example of how he develops this idea (RL.7.2).

Develop an understanding of the suffix –ian through example and study of the word Orwellian, and then apply this understanding to define other new words (L.7.4.b).

30 FQT Animal Farm Know

How does Animal Farm build my knowledge of the dangerous power of language?

Execute

How do I use a strong claim, clear reasons, and relevant evidence in an argument paragraph? Execute

How do I effectively and purposefully vary sentences in a written argument?

Write an argument paragraph for your teacher and classmates about the most important theme about the power of language that Orwell develops in Animal Farm, supporting the claim with clear reasons and relevant evidence (RL.7.1, RL.7.2, W.7.1, W.7.4, W.7.9.a, L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a).

Vary sentence structures to emphasize important ideas and signal differing relationships in a written argument (L.7.1.b).

31 Review of Animal Farm, George Soule

Review of Animal Farm, Michael Berry

Review of Animal Farm, Bapalapa2, student reviewer

What does a deeper exploration of book reviews reveal?

Experiment

How do introductions work?

Compare and contrast multiple authors’ reviews of Animal Farm, analyzing differing interpretations and evidence (RI.7.9).

Draft an introduction paragraph using the HIC structure (W.7.1.a).

Develop a deeper understanding of and accurately use the term satire (L.7.6).

32 NR “Why You Should Read Animal Farm”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the argument in a book review reveal?

33 Animal Farm Know

How do the book reviews build my knowledge of how and why language influences thought and action?

Experiment

How does organizing and concluding an argument work? Excel

How do I improve my book review?

Trace and evaluate an Animal Farm review’s argument, assessing whether the author’s reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to support the claims (RI.7.1, RI.7.4, RI.7.8 W.7.10, L.7.4.a).

Analyze a book review website to identify its purpose and audience.

Integrate understanding of the roots lit and litera to define and use words (L.7.4.b).

Publish a book review arguing that an audience should or should not read Animal Farm (W.7.1, W.7.4, W.7.6).

34 EOM VOC

All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how and why language influences thought and action?

35 All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how language influences thought and action?

Execute

How do I use claims, reasons, and relevant evidence in an argument essay plan?

Plan an argument essay about language and power, identifying relevant evidence (W.7.5).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary and how to use affixes and roots as clues to the meanings of words or phrases (L.7.4.b, L.7.6).

Execute

How do I use the elements of an effective argument in an argument essay?

Develop an argument essay about language and power, supporting claims with logical reasoning and relevant evidence (RL.7.1, RI.7.1, W.7.1, W.7.4).

Delineate a partner’s argument about language and power, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence (SL.7.3).

Focusing Question 4: How and why does language influence thought and action?36 All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how language influences thought and action?

Excel

How do I improve my argument essay?

Excel

How do I improve my argument to show command of English grammar, language, conventions, vocabulary, and style?

37 SS All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of the power of language?

Provide and receive feedback to revise EOM Task essays and meet criteria for success (W.7.5).

Demonstrate an understanding of how to use precise and concise language, purposeful varied sentence structures, and a style appropriate for argument writing (L.7.1.b, L.7.3.a, L.7.6, W.7.4, W.7.5).

Engage in a collaborative conversation about language and power, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Review and deepen understanding of words, phrases, and morphemes learned throughout the module (L.7.6).

Focusing Question 4: How and why does language influence thought and action?Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (10 min.)

Learn (52 min.)

Notice and Wonder (27 min.)

Experiment with Figurative and Sensory Language (25 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (3 min.)

Assign the Volume of Reading Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Inspire (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.7.1, RL.7.4 Writing W.7.10

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.2

Language L.7.5.a L.7.4.b

Handout 1A: Poetry Terms

Formulate questions and observations about “B” (RL.7.1).

Complete a Notice and Wonder T-Chart.

Experiment with figurative and sensory language inspired by “B” (W.7.3.d).

Write examples of personification, metaphor, and simile inspired by “B.”

Develop a clear understanding of the word inspire based on its Latin root and dictionary definition (L.7.4.b).

Submit an Exit Ticket explaining how the core lesson’s Land quotation reflects the definition of inspire and its Latin root.

What is the power of language?

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–11

How and why does language inspire?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about “B”?

CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 1

Experiment: How do figurative language and sensory language work?

Focusing Question 1 kicks off Module 3’s exploration of the power of language by prompting students to consider how and why language inspires. This first lesson hooks students with the uniquely moving “B,” a spoken word poem that could shatter any cynic’s notion of poetry as abstruse or dull. The poem’s rich yet accessible language provides a useful springboard for students’ own poetry experimentation.

5 MIN.

Have students respond to the following in their Response Journal: “Imagine a child who could learn about life from you. The child could be someone you know, such as a younger cousin, or an imaginary child, such as a hypothetical future son/daughter or fictional character. Brainstorm a list of things you would tell or teach this child about life.”

Display a few items you might add to your list. For example, “I’d teach my future nephew how to bake rainbow cupcakes,” and “I’d tell him that standing up for what’s right is sometimes tough but always worth it.”

10 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question.

Ask what the word powerful means. Then ask what it might mean for language to be powerful.

Ask: “How would you feel if someone you admired gave you advice like you wrote in the Welcome task?”

If students do not use the word on their own, explain that some people might use the word inspire to describe how such advice affects them.

Ask for students’ current understanding of the word inspire. Then provide the following definitions for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

inspire (v.) 1. To fill someone with positive emotions, feelings, or thoughts.

2. To cause an increase in one’s desire to accomplish or create something, or to make a positive change in one’s life or attitude.

Have small groups share their Welcome task lists, and encourage them to add ideas to their lists if they become inspired by their peers.

Then ask the whole group: “In your opinion, which ideas from your list are inspiring?” Invite a few students to share.

Explain that students will begin investigating how and why language inspires by exploring inspirational poems.

52 MIN.

27 MIN.

Distribute Handout 1A. Explain that the listed terms are ones students have already learned. They will continue to add terms to enrich their writing and discussion about poetry. Ask pairs to review the definitions and jot a few examples in the third column.

Ask for an example to illustrate each term.

Consider displaying an anchor chart of poetry terms, allowing all students to easily refer to it during discussion and writing.

Explain that students will view “B,” a spoken word poem by Sarah Kay. Inform students that spoken word is the term for poetry that is intended to be performed, rather than just written on the page.

Tell students that on the first viewing of “B,” they should see what they notice and be prepared to share their observations.

Play “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter)” (http://witeng.link/0314).

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What do you notice about ‘B’”?

n Kay made “B” meaningful and relatable by addressing ideas like heartbreak and happiness.

n Kay specifies a daughter, but her hopes and advice could apply to any person.

n Kay acknowledges that life is full of pain but emphasizes that we should stay determined, curious, and positive. It’s inspiring.

n The poem is mainly made up of figurative language.

n Kay uses vivid images and unique language that make the poem engaging.

n The poem doesn’t rhyme.

n The lines are unique and unexpected.

Tell students they will view “B” again. This time, they should use a Notice and Wonder T-Chart to jot the most striking quotations that they notice as well as what they wonder.

Students record their questions and observations on their T-chart, referring to the written text as needed.

After replaying the poem and providing time for students to add to their T-chart, have pairs discuss the striking quotations they noticed, why they found these quotations striking, and what they wondered. Encourage pairs to seek answers to their questions in the text.

Ask the whole group: “What is the most striking quotation you noticed, and why?” Emphasize that students should honestly answer why they are drawn to certain points in the text and that this question has no wrong answers. Have students share.

n “There’s nothing more beautiful than the way the ocean refuses to stop kissing the shoreline no matter how many times it is sent away.” This figurative language strikes me because the persistent ocean reminds me that you should never give up.

n “Life will hit you hard…but getting the wind knocked out of you is the only way to remind your lungs how much they like the taste of air.” I like how Kay depicts life here because she doesn’t pretend that life always feels pleasant. At the same time, this gives me a positive feeling.

n “I am going to paint the Solar Systems on the backs of her hands.” This image is surprising and beautiful to visualize. It reminds me how big our world is and how much there is to learn.

Ask follow-up questions to deepen thinking about what students notice in “B.”

What idea does that quotation make you think about?

How does that line make you feel?

Which of your quotations are examples of figurative language? Which use sensory language?

What is the term for that literary technique?

Then ask: “What did you wonder about?”

n Kay says she wants her daughter to “look through a microscope at the galaxies that exist on the pinpoint of a human mind.” What does that mean?

n What’s the meaning of the word winsome?

n Kay’s words are caring and supportive. I wonder if her parents acted that way.

Rather than interpreting parts of the poem for students, ask the whole group for their thoughts about any questions raised, encouraging them to refer to the written text whenever possible. Provide definitions for unknown vocabulary.

Ask students what they notice about additional literary elements and techniques, such as mood, metaphors, similes, personification, and alliteration.

“B” is the first section of Sarah Kay’s moving TED Talk about the value of poetry (http://witeng.link/0155). Consider showing students the full talk to stimulate their motivation to experiment with craft in the next activity and to emphasize its value.

Individuals

Display the Craft Question: How do figurative language and sensory language work?

25 MIN.

Have students take out their Welcome task response. Explain that students will use the ideas they listed to experiment with their own figurative and sensory language inspired by “B.”

Remind students that they wrote metaphors and similes during their study of the Middle Ages. Explain that another useful type of figurative language is called personification. Have students add the following to Handout 1A.

personification (n.) The act of attributing human characteristics to nonhuman things.

Explain that an example of personification in “B” is the sentence, “life will hit you hard,” because hitting is an action that humans can do, but life is nonhuman.

Ask: “Where else do you see personification in ‘B’? Add at least one example to Handout 1A.” Then have students share.

n Life will “wait for you to get back up, just so it can kick you in the stomach.”

n “Remind your lungs how much they like the taste of air.”

n “The ocean refuses to stop kissing the shoreline no matter how many times it is sent away.”

To ensure students remember how to write metaphors and similes, have students identify examples in the text.

Then ask students to identify a few places in which the figurative language incorporates sensory language. For example, students may point out that they can visualize the personified ocean returning to the shoreline.

Display the following prompt: “Draft at least three original lines that convey what you might say to the person you had in mind when you completed your Welcome task. Write at least one example of personification, one metaphor, and one simile.”

Begin by collaboratively writing a few lines with the whole group. For example, you might say, “I’d want a future little cousin to know he can depend on me, so I want to write a metaphor comparing myself to something that represents that. What’s an example of something that’s dependable? Can you think of a dependable object, person, animal, or natural element?”

Consider offering the option to collaborate. Also provide the following optional sentence frames for writers who need more support.

The world is a because

Heartbreak will Friendship is like .

(metaphor) (personification) (simile)

Challenge advanced students to develop short poems inspired by “B.”

Remind students to be original, avoiding clichés such as, “Life is a rollercoaster.”

Students independently write their examples of personification, metaphor, and simile in their Response Journal.

Have students share in small groups. Then invite a few students to share their favorite lines with the whole group.

Have all students write short poems inspired by “B.” Consider providing the following optional template: If I should have a , instead of , they are going to call me because

And I’m going to And they’ll learn that life will . I want them to know the world is like .

(person you’re writing to) (what they might actually call you) (name that represents your role in their life) (reason for that name) (something you could do to teach them a lesson from your Welcome list) (use personification) (use a simile)

Encourage stronger writers to abandon the template and simply use the types of figurative language that best express their ideas.

Land 5 MIN.

Have students revisit the definition of the word inspire. Then facilitate a Whip Around to have students share the most inspiring quotation from the lesson, whether it is from “B” or from a student’s figurative language example.

3 MIN.

Distribute and review the list of additional texts from Appendix D: Volume of Reading, and the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions. Explain that the list contains books with further information about topics discussed in the module. Tell students that they should consider the reflection questions as they independently read any additional texts and respond to them when they finish a text.

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal, or submit them directly. The questions can also be used as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide (http://witeng.link/IG) for a further explanation of Volume of Reading as well as various ways of using the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions.

To ensure students remember how to write metaphors and similes, have students identify examples in the text.

Students use T-charts to record the most striking quotations they notice in “B” as well as what they wonder (RL.7.1). Each student:

Identifies quotations from “B” and is able to articulate why each quotation is striking when prompted.

Asks questions based on specific points in the text.

This lesson presents an opportunity for students to become comfortable discussing poetry. If they struggle, emphasize that all text-based observations and questions are legitimate. Also consider starting by having students collaboratively annotate “B” with their observations and questions.

Time: 15 min.

Text: “ ‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay (http://witeng.link/0314)

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Develop a clear understanding of the word inspire based on its Latin root and dictionary definition (L.7.4.b).

Vocabulary Deep Dives 20 and 34 provide vocabulary assessment tools and corresponding directions. To best meet students’ language needs, consider using these tools to assess students at the start of this module. Do not share results with students, but use the data to inform and differentiate vocabulary instruction. At the close of the module, reassess students using the same tool to determine their growth against the baseline data.

Explain that this lesson will help students develop a strong and precise understanding of the word inspire to ensure that, as they explore the Focusing Question and texts, their writing and discussions about inspiring language are clear and purposeful.

Ask a student to remind the class of the definitions of inspire from their Vocabulary Journal.

n To fill someone with positive emotions, feelings, or thoughts.

n To cause an increase in one’s desire to accomplish or create something, or to make a positive change in one’s life or attitude.

Provide the following definitions for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

in– (prefix)

spir spiro (Latin root)

In, on, onto.

Breathe, blow into.

Clarify that the prefix in– has multiple definitions. Students may already be aware that in– can mean “not,” as it does in the word inaccurate. It can also mean “in, on, onto,” as it does in the words incarcerate and inspire.

Then instruct students to independently jot an explanation of how the meanings of this prefix and Latin root relate to the Vocabulary Journal definitions of inspire. Also consider offering the option of drawing to reflect this connection.

Have small groups brainstorm other words that use this root, such as perspire, conspire, and spirit. Spanish-speaking students may observe the root’s presence in the Spanish word for breathe, respirar.

Have small groups share their responses, and then ask a few students to share with the whole group.

n Breathing is associated with life, so breathing into something is like giving life and energy.

n When you inspire someone you give life to their ideas, exerting a stimulating influence.

n If something inspires you, it’s like it breathes life into you and motivates you to accomplish or create something, or to make a positive change.

n When you inspire someone, you give life to emotions and thoughts. This is similar to how breath keeps our bodies going.

Instruct students to continue to refer to their Vocabulary Journal definition of inspire as they jot one or two examples of times when they have been inspired and then explain how the examples fit the inspire definitions.

Have small groups share.

Have students create a one- or two-sentence example of personification that expresses the role of inspiration in life. Advise students to refer to their example for inspiration and ask themselves: “How can I personify inspiration to show its meaning?”

Responses will likely be more creative without modeling, but if students need more support, Think Aloud with a small group or the whole class.

When I think about times I feel inspired, I think of each morning when I wake up. I’m sleepy at first, but when I consider the day ahead, inspiration stirs my thoughts and I feel excited to accomplish important things. I want to show how inspiration stirs thoughts and awakens me, so I’ll personify inspiration as someone with this impact: “Inspiration stands at the stove flipping thoughts like pancakes. When my alarm buzzes, she skips into my room to pull me out of bed.”

Students revisit the inspiring quotation they identified during the core lesson’s Land and respond to an Exit Ticket prompt about this quotation: “How does this quotation fit your Vocabulary Journal definitions of inspire? How does the quotation reflect the meaning of the Latin root of inspire?”

“‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay (http://witeng.link/0314) “Don’t ever apologize for the way your eyes refuse to stop shining” (http://witeng.link/0315)

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (5 min.)

Learn (59 min.)

Analyze Language (34 min.)

Analyze Performance Techniques (25 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (1 min.)

Assign Homework

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content

Vocabulary: Winsome (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.7.1, RL.7.4, RL.7.5, RL.7.7

Writing W.7.10

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.2

Language

L.7.5.a L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b

Handout 1A: Poetry Terms

White paper

Colored pencils or markers

Analyze how Kay uses language to inspire her audience (RL.7.4).

After creating a visual representation of a quotation from “B,” analyze the quotation.

Identify and analyze the performance techniques Kay uses to enhance “B” (RL.7.7).

Complete a chart analyzing two examples of performance techniques.

Analyze Kay’s use of the word winsome based on its context and morphemes (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Submit an Exit Ticket explaining how the word winsome helps reveal a central idea in “B.”

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–11

How and why does language inspire?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Reveal: What does a deeper exploration of language and performance techniques reveal in “B”?

In this lesson, students first analyze the written language in “B,” and then they analyze how Kay expresses those words on the stage. This is a collaborative study that prepares students to analyze poetic language and performance more independently in upcoming lessons.

5 MIN.

In their Response Journal, have students use personification to finish the following sentence based on a line from “B”: “Sure, life will hit you hard in the face sometimes, but life will also … ”

Challenge students to write a sentence that expresses an idea they truly believe in, rather than the first words that come to mind.

5 MIN.

Post the Focusing Question and Content Framing Question. Explain that students will look more deeply at the poem’s language, and they will also explore how Kay structures and performs the poem.

Ask a few students to briefly remind the class what “B” is about and what they noticed about its language in the last lesson. Students should understand that “B” frequently uses sensory and figurative language.

Remind students that using sensory and figurative language is something writers of all genres—not just poets—do. Have students Whip Around to share their personification examples.

Display the following quotation from “B.”

And when they finally hand you a heartache, when they slip war and hatred under your door and offer you handouts on street corners of cynicism and defeat, you tell them that they really ought to meet your mother.

First, explore what students know about the word cynicism. Clarify its meaning as needed.

Then discuss the following TDQs with the whole group with reference to this quotation to support students in closely analyzing Kay’s language.

1. What literary terms can you use to describe the language in the quotation, and why? What idea does this language express?

n Kay uses figurative language. For example, it’s not possible to literally give someone a handout of cynicism or defeat on a street corner.

n Kay uses a specific type of figurative language: metaphors. For example, she compares hatred to something you could slip under a door, like a piece of paper. This shows how easily hatred can spread.

n Kay uses sensory language. For example, she creates the image of the door.

n This language shows that pain and challenges are everywhere. Kay suggests that cynicism is so common, it’s like a handout offered on street corners. However, she suggests that her daughter shouldn’t accept “handouts” of cynicism and defeat and that it is possible to remain optimistic—especially with the support of a parent.

2. “B” doesn’t rhyme, but it does use another type of repeating sound: alliteration, which indicates a repeating consonant sound. Where in the stanza above does Kay use alliteration? How does the alliteration affect this stanza?

n The “H” sound is repeated in hand, heartache, hatred, and handouts

n The alliteration makes this stanza sound more engaging and memorable, which is appropriate because it’s the final stanza. It’s catchy and has a satisfying flow.

n The alliteration helps connect the ideas. These words are mostly negative, and they come quickly at the beginning of the stanza. This emphasizes that negativity can spread relentlessly. However, the alliteration ends when Kay says to tell them they “really ought to meet your mother,” shifting to a positive idea.

Have students add the following terms and definitions to Handout 1A.

alliteration (n.) The repetition of the same consonant sound in the beginning or stressed syllables of words in a sentence or phrase or line of poetry. stanza (n.) A section of a poem, made up of a group of related lines.

Extension

Have small groups create alliteration tongue twister examples.

3. Another term for sensory language is imagery Examine the imagery in the stanza above. What is its impact?

n Kay creates the image of war being slipped under the daughter’s door.

n This image is unexpected and unique, which engages the reader. It stirs the reader’s imagination.

n The image reinforces the idea that there’s pain in life and we will have to confront it, almost like we can’t avoid a piece of paper that’s been slipped under our door.

Have students add the following to Handout 1A.

Word

imagery (n.) Visually descriptive language, especially in a literary work.

n The tone is positive, caring, sincere, and honest.

n She comforts her daughter, emphasizing that she will be there to support her daughter through challenges.

n She is honest as she admits her daughter will encounter things like heartache.

Tell students that the next activity will allow them to use both their creative and analytical skills. Distribute white paper and colored pencils or markers to pairs.

Instruct pairs to select one striking quotation from “B.” Explain that they should write the quotation on their white paper using creative lettering, and on that same paper, they should illustrate at least one image from the quotation. Consider showing this model: http://witeng.link/0315. However, reassure students that simpler illustrations and stick figures are fine, as long as they are creative and thoughtfully represent the quotation.

Have students add a caption to their illustrations that responds to the following questions.

1. What image does the sensory language depict? What is its impact?

2. What other terms can you use to describe the language here? What idea does this language express?

Students write captions for their illustrations in response to the questions.

Some students may benefit from a handout that designates spaces for them to draw their illustration and quotation and respond to questions 1 and 2. Also consider adding a word bank featuring the terms personification, metaphor, sensory language, and figurative language.

In addition, consider offering extra credit for taking the activity home and developing it with paint, collage, or film. This is one way to honor multiple intelligences as well as promote sustained thinking about the text.

Have small groups share. Invite a few students to share with the whole group.

Conduct a Gallery Walk, and then have students point out specific aspects of various pictures that they appreciated.

Now that students have explored sensory and figurative language more deeply, have them return to the figurative language examples they wrote in the last lesson and consider revisions. Would they be able to illustrate that sensory language the way they did with “B”? Where might they add vivid sensory detail?

Tell students that although purposeful language plays an essential role in inspiring an audience, the way the writer chooses to present that language can have a major effect on the words. Students will explore this by considering structure, form, and performance techniques in “B.”

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “How can you describe the form and structure in “B”? How does this contribute to its meaning?”

n It doesn’t seem to use a rigid structure like a haiku. It sounds natural and free. This helps Kay sound genuine and passionate, like the words are flowing from her.

n The written poem organizes ideas in stanzas, which makes them easier to read.

n The line, “Believe me, I’ve tried,” is on its own in between two longer stanzas. This makes the line stand out to the reader. The reader sees that it’s important that the mother has personally struggled in life and wants to share what she’s learned.

If students do not mention it, guide them to see that the type of poem, spoken word, impacts the poem’s meaning as well.

Tell students that they will view the poem (http://witeng.link/0314) again. Explain that as they watch, they should jot a list of performance techniques Kay uses. Share an example, such as the observation that Kay speaks quickly at several points.

After playing the video, ask what performance techniques students noticed. As students share, chart their responses and have students do so in their Response Journal.

n Speak faster and more slowly.

n Increase and decrease volume.

n Pause.

n Emphasize particular words and phrases.

n Use body language and facial expressions.

n Speak expressively, changing your tone of voice.

If time is scarce, consider providing the list of techniques and having students focus on analyzing the listed techniques’ roles in Kay’s performance.

Have students create the following chart in their Response Journal. Then have them select three performance techniques from the list that they want to analyze in more depth as they watch “B” again.

Technique Example from “B”

How does this impact the words of the poem?

After viewing “B” again, students analyze three performance techniques using the graphic organizer, referring to the written text as needed.

Have students share.

Extension

Spoken word poetry is an engaging entry point to the study of poetry and language for many students. Consider having students explore additional spoken word poems online, take a field trip to a local poetry slam, and perhaps even host their own class poetry slam. For interested students, you might also recommend Louder Than a Bomb, an awardwinning documentary about a high school poetry slam competition.

Land5 MIN.

Students submit an Exit Ticket in response to the following: What does a deeper exploration of the language in “B” and the performance techniques Kay uses reveal about what makes language inspiring?

1 MIN.

Inform students that there is no homework for this lesson.

Students write captions for illustrated language to analyze its meaning (RL.7.4). Check for the following success criteria:

Uses a precise term to describe the language.

Clearly explains how the language expresses a specific idea.

If students struggle to articulate clear and specific analyses, provide the following sentence frames and collaborate with a group that needs more support to use them.

This is an example of because . The words and suggest that , helping Kay express the idea that .

Time: 15 min.

Text: “‘B’ (If I Should Have a Daughter),” Sarah Kay (http://witeng.link/0314)

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Analyze Kay’s use of the word winsome based on its context and morphemes (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Display the following quotation from “B”: “You will put the win in winsome … lose some. / You will put the star in starting over and over.”

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What context clues signal what winsome might mean?”

n I’ve heard people say, “You win some and you lose some.” It means you can’t always win, but that’s OK. Kay is alluding to that saying.

n Winsome must be the opposite of losing. Maybe it means something similar to winning.

n Kay has a loving attitude toward her daughter in the poem, so winsome is probably positive.

n We can tell it’s a word that helps support the idea that starting over and over is not a bad thing.

Ask small groups to brainstorm a list of words that end with the suffix –some.

Then chart responses.

n Awesome.

n Troublesome.

n Bothersome.

n Cumbersome.

n Gruesome.

n Lonesome.

n Tiresome.

Ask what these words have in common, and guide students as needed to see that they are all adjectives.

Provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

some (suffix)

Characterized by.

Explain that the Old English root wynn, from which win is derived, means “joy.” Then instruct small groups to draft definitions for winsome based on its morphemes and context.

Collaboratively draft a definition with the whole group, and then have students add the definition to their Vocabulary Journal.

winsome (adj.)

Charming, appealing, or attractive. charming, appealing, attractive

Remind students that they analyzed alliteration in “B” during the core lesson. Instruct small groups to create one to three alliterative sentences that show the meaning of the word winsome.