Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms. Printed in the USA A-Print

Module Summary 2 Essential Question 3 Suggested Student Understanding 3 Texts 4 Module Learning Goals 5 Module in Context............................................................................................................................... ........................ 6 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 7 Major Assessments 9 Module Map 11

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–7 What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker? Lesson 1 ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 23

n TEXTS: “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.,” Alexis O’Neill (Handout 1A) • “Americans All” poster • “United We Win” poster ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Marginalization, segregation, equality Lesson 2 ............................................................................................................................... ........................ 37

n TEXT: Code Talker, Joseph Bruchac, “Listen, My Grandchildren” ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Sacred and the morpheme sacr Lesson 3 49

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapter 1 ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Reassure, remember Lesson 4 ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 61

n TEXT: Code Talker, pages 5–11 and 215–218

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Bleak, brutal, catastrophic Lesson 5 ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 73

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 2–3 ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Precise and Concise Writing Lesson 6............................................................................................................................................................................................ 87

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 4–5 ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Precise Writing

Lesson 7 ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 99

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 1–5

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Culture, tradition

How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?

Lesson 8 109

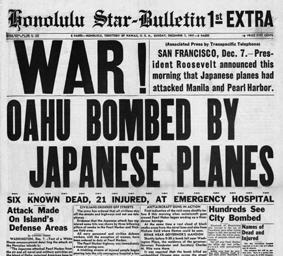

n TEXTS: Code Talker, Chapter 6 • “Pearl Harbor and World War II,” Brandon Marie Miller and Mark Clemens (Handout 8C) • Images of Pearl Harbor headlines

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: The Suffix –ism

Lesson 9.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 125

n TEXTS: Code Talker, Chapters 7–8 • Images of Pearl Harbor headlines

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Motto

Lesson 10 139

n TEXTS: Code Talker, Chapter 9 and pages 222–223 • “A Beautiful Dawn,” Radmilla Cody

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Formal Style

Lesson 11 153

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapter 10

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Transitional Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 12 ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 167

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 11–12

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 13 ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 183

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 13–14

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Offensive Lesson 14 ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 193

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 15–17

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Formal Tone

Lesson 15 209

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 18–20

¢

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Concise Writing

Lesson 16 221

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapters 21–23

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Misplaced Modifiers

Lesson 17 ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 233

n TEXTS: Code Talker, Chapters 24–26 • Photograph of Flag Raising on Iwo Jima, 02/23/1945, Joe Rosenthal

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Pulverized

Lesson 18 ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 243

¢ TEXTS: Code Talker, Chapters 27–28 • “Navajo Code Talkers,” Harry Gardener (Handout 18A)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Transitional Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 19 255

n TEXT: Code Talker, Chapter 29

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment

Lesson 20 265

n TEXT: Code Talker

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Sentence Structures

Lesson 21 ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 275

n TEXTS: Code Talker • Ansel Adams photographs (Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office; Manzanar from Guard Tower; School Children)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Dangling Participles

Focusing Question: Lessons 22–31

What did the Wakatsukis experience during World War II, and how did it affect them?

Lesson 22 287

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston, Chapter 1

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Interrogation and Its Morphemes

Lesson 23 299

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar, pages 9–13 • “Relocation Camps,” Craig Blohm (Handout 23A)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Formal Style and Tone

Lesson 24 ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 309

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar, Chapter 2 • “World War II Internment of Japanese Americans,” Alan Taylor • “Relocation Camps” (Handout 23A)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute with Transitional Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 25 321

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar, pages 21–34

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Subordinate, communal, integrated

Lesson 26 331

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar, pages 31–41 and 61–64

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Sentence Structures

Lesson 27 ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 341

n TEXTS: Ansel Adams photographs (Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office; Manzanar from Guard Tower; School Children)

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Geometric, organic, symmetrical, asymmetrical

Lesson 28 ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 355

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar, pages 71–78

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Formal Style and Tone

Lesson 29 ............................................................................................................................... .................... 365

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar, pages 113–114, 142–149, and 167–176

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Prevail, strive, endure

Lesson 30 377

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar • Code Talker

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Modifying Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 31 387

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar • Ansel Adams photographs (Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office; Manzanar from Guard Tower; School Children)

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment

How did World War II affect individuals?

Lesson 32 395

n TEXT: Farewell to Manzanar

Lesson 33 401

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar • Code Talker

Lesson 34 407

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar • Code Talker

Lesson 35 ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 413

n TEXTS: Farewell to Manzanar • Code Talker ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Language Skills

GRADE 7 MODULE 2

The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it.

—Chief JosephThe history of the past is but one long struggle upward to equality.

—Elizabeth Cady StantonBy the late 1930s, the world was wracked by economic despair and facing rising fascist powers. Democracy looked weak, inadequate, and doomed. Hitler’s racially obsessed state loomed large over Europe, annexing Austria, allying with fascist Italy, and threatening to invade its neighbors. Americans were suspicious of Nazi sympathizers, but many feared that Germany could not be stopped.

In the Pacific, tensions were also mounting. An actively modernizing Japan emerged as a rising world power. Japan’s economy had suffered during the Great Depression, and in the 1930s, the nation increasingly came under military control. Espousing doctrines of national and racial supremacy, Japan’s expansionism into China in 1937 further strained relations with the West.

As relations with Japan deteriorated, the U.S. imposed embargoes on oil and other materials that Japan desperately needed. Japan viewed these measures as threats to its very existence, and in 1940, joined the Axis alliance with Germany and Italy, plotting massive invasions throughout East Asia. Japan feared that America’s industrial resources and manpower would overwhelm Japan in a prolonged war and hoped to stun the U.S. into negotiating peace. To that end, Japan launched a surprise air attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. America’s Pacific fleet was badly damaged—and America responded to the attack with fury and indignation. Hitler was convinced that the conflict with the U.S. was inevitable, and he was determined to stop American aid to Britain and Russia. Hitler declared war.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war instantly shattered America’s isolationist mood. Through the draft and widespread voluntary enlistment, young men everywhere were swept into war. A shared patriotic purpose united Americans.

As the war expanded, Germany imposed tyrannical control in the territories it conquered—forcing people into slavery, stealing their wealth, and using its feared secret police to brutally suppress dissent. An increasingly mechanized extermination system, centered on slave labor and death camps, ran ceaselessly until the war’s end. Six million Jews were murdered, while millions of other Europeans were worked to death alongside them.

Meanwhile, the American military remained racially segregated. As the U.S. fought against racially bigoted regimes abroad, many Americans noted the blatant disconnect and argued for reform at home.

Populations linked to enemy nations were at the greatest risk of government discrimination. On the West Coast, Japanese Americans faced accusations—often founded on blatant prejudice and encouraged by neighbors’ schemes to seize Japanese American property—of disloyalty and sabotage. More than 100,000 Japanese living on the West Coast, more than half of whom were U.S. citizens, were interned in federal camps (although men could win release to join the U.S. military, and many served with distinction).

Through the fictional account of Ned Begay, a Navajo teenager called to war, and the memoir of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, a former internee of Manzanar camp, students explore this world conflict by entering the lives of those who lived through it. In Code Talker, by Joseph Bruchac, the protagonist experiences assimilation and battlefield combat, yet his Navajo culture provides him strength, selfawareness, and language—all of which create a remarkable opportunity to serve his country. In Farewell to Manzanar, young Jeannie struggles to understand and come to terms with the effects of her family’s wartime internment. From these unforgettable stories, students gain insight into the World War II era.

The End-of-Module (EOM) Task is an informative/explanatory essay. In it, students detail how one individual encountered adversity and/or opportunity as a result of the war, and how they formed identity in a time marked by challenge on both a national and human scale.

How did World War II affect individuals?

World War II presented new opportunities and challenges for Americans.

Navajo Americans and Japanese Americans have made indispensable contributions to American society throughout history.

Cultural identity can be a source of strength and pride.

Stories about individuals can help us understand the larger forces that shaped a particular era.

Memoir (Informational)

Farewell to Manzanar, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston

Novel (Literary)

Code Talker, Joseph Bruchac

Biography

“Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.,” Alexis O’Neill

Historical Account

“Navajo Code Talkers,” Harry Gardiner

“Pearl Harbor and World War II,” Brandon Marie Miller and Mark Clemens

“Relocation Camps,” Craig Blohm

“World War II Internment of Japanese Americans,” Alan Taylor (http://witeng.link/0069)

Journalism

Pearl Harbor headlines

Music

“A Beautiful Dawn,” Radmilla Cody (http://witeng.link/0024)

Manzanar from Guard Tower, Ansel Adams (http://witeng.link/0039)

Photograph of Flag Raising on Iwo Jima, 02/23/45, Joe Rosenthal (http://witeng.link/0038)

Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office, Ansel Adams (http://witeng.link/0040)

School Children, Ansel Adams (http://witeng.link/0041)

“Americans All” (http://witeng.link/0004)

“United We Win” (http://witeng.link/0003)

Summarize the experiences of Japanese Americans and members of the Navajo tribe—before, during, and after World War II.

Identify the effects of cultural assimilation on Navajo individuals, as shown through the story of Code Talker’s protagonist.

Describe the role of the Navajo code talkers in the United States’ World War II victory, and explain how the war affected Navajo individuals.

Explain the causes of the Japanese internment, daily life at Manzanar camp, and the internment’s effects on Japanese American individuals.

Identify the basic facts of World War II, including Pearl Harbor’s role in escalating U.S. involvement and the major theaters of the war.

Analyze the central ideas of Code Talker and Farewell to Manzanar (RL.7.2, RI.7.2).

Analyze how discrimination, war, and citizenship influenced Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and her family (RI.7.3).

Analyze how elements of Code Talker interact—particularly how the wartime setting influences Ned’s identity (RL.7.3).

Craft a well-organized informative/explanatory essay that analyzes the wartime experiences of either Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston or Ned Begay, developing the topic with relevant details and quotations (W.7.2, W.7.2.b).

Produce informative writing that introduces a topic clearly, uses effective transitions, and concludes ideas effectively (W.7.2.a, W.7.2.c, W.7.2.f).

Attend to task, purpose, and audience with intentional decisions around content and style (W.7.2.d, W.7.2.e, W.7.4).

Develop and strengthen writing by engaging in a process of planning, drafting, editing, revising, and publishing (W.7.5).

Emphasize important points when speaking (SL.7.4.).

Overcome listening barriers.

Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate (SL.7.6).

Analyze the relationship between target vocabulary (synonyms, antonyms, or both) to better understand and apply each of the words (L.7.5.b).

Use transitional phrases and clauses to connect ideas within and between paragraphs (L.7.1.a).

Use precise and concise language when writing topic sentences and evidence sentences, and eliminate wordiness and repetition in writing (L.7.3.a).

Explore the meaning of grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots to clarify the meaning of target vocabulary (L.7.4.b).

Spell correctly (L.7.2.b).

Knowledge: Module 2 builds on Module 1’s exploration of identity in society. In Module 1, students built a foundational understanding of the concept of identity in the rigidly hierarchical Middle Ages and explored how structures can influence a society. In Module 2, students consider the influences of race, culture, war, and patriotism on identity, both individual and national.

Reading: In Module 1, students read narrative texts and analyzed how medieval settings developed characters’ identities. In Module 2, students continue to explore the influence of setting on character. Students analyze the impact of Code Talker’s World War II setting on the protagonist’s identity. They also analyze interaction between plot and character. Additionally, students extend their reading skills with a new focus on informational texts. By studying Farewell to Manzanar and several historical accounts about World War II, students make the jump from identifying literary themes to identifying informational central ideas. They also analyze the interaction between individuals, events, and ideas such as citizenship.

Writing: Students extend their writing skills by moving from Module 1’s focus on narrative writing to Module 2’s focus on informative writing. In their informative writing, students use many of the narrative writing skills they learned, such as using descriptive language, while developing new skills such as writing introductory paragraphs.

Speaking and Listening: In Module 2, students apply Module 1’s focus on how to set speaking goals and track progress. Students learn how to emphasize important points when speaking and to overcome listening barriers when listening, and they track their progress during the module’s Socratic Seminars.

RL.7.2 Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

RL.7.3 Analyze how particular elements of a story or drama interact (e.g., how setting shapes the characters or plot).

RI.7.1 Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

RI.7.2 Determine two or more central ideas in a text and analyze their development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

RI.7.3 Analyze the interactions between individuals, events, and ideas in a text (e.g., how ideas influence individuals or events, or how individuals influence ideas or events).

W.7.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content.

W.7.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. (Grade-specific expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1–3.)

W.7.5 With some guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on how well purpose and audience have been addressed. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1–3 up to and including grade 7 here.)

L.7.1.a Explain the function of phrases and clauses in general and their function in specific sentences.

L.7.1.c Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers.

L.7.2.b Spell correctly.

L.7.3.a Choose language that expresses ideas precisely and concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy.

L.7.4.b Use common, grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (e.g., belligerent, bellicose, rebel).

L.7.5.b Use the relationship between particular words (e.g., synonym/antonym, analogy) to better understand each of the words.

SL.7.4 Present claims and findings, emphasizing salient points in a focused, coherent manner with pertinent descriptions, facts, details, and examples; use appropriate eye contact, adequate volume, and clear pronunciation.

SL.7.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

RL.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

RI.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

L.7.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

1. Use an evidence guide to identify important aspects of Ned Begay’s Navajo identity in Code Talker

2. Write a paragraph that analyzes how a particular aspect of Navajo culture supports Ned Begay over the course of Code Talker.

3. In two paragraphs, analyze how Wakatsuki Houston develops two central ideas over the course of Farewell to Manzanar

Identify aspects of Navajo culture.

Demonstrate foundational understanding of Ned’s Navajo identity.

RL.7.1; L.7.2

Demonstrate understanding of how Ned’s wartime experiences affect his identity.

Write an evidence-based informative paragraph.

RL.7.1, 7.3; W.7.2, 7.4; L.7.1.a, L.7.1.c, L.7.2.b, L.7.3.a

Demonstrate understanding of how Wakatsuki Houston’s experience at Manzanar affected her.

Organize and develop a set of informative paragraphs. Write an effective introductory paragraph.

RI.7.1, 7.2; W.7.2, 7.4, 7.9; L.7.1.c, L.7.2.b, L.7.3.a

1. Read chapter 14 of Code Talker Then respond to multiple-choice questions and two writing prompts to demonstrate comprehension.

2. Read pages 34–41 of Farewell to Manzanar. Then respond to multiple-choice questions and write a summary.

Demonstrate comprehension of Code Talker’s World War II setting.

RL.7.1, 7.2, 7.3

Analyze how Ned’s identity develops.

Analyze the internment’s impact on individual members of the Wakatsuki family. Analyze the internment’s impact on the family unit.

RI.7.1, 7.2; L.7.2.b, L.7.4.a

1. Identify which aspects of Navajo culture are significant to Ned Begay at school, and explain and how these cultural aspects impact him.

Demonstrate an understanding of the role Navajo culture plays in Ned’s identity.

2. Analyze the themes and central ideas of Code Talker

3. Compare and contrast Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s wartime experience with Ned Begay’s.

Demonstrate an understanding of key ideas about Ned’s wartime experience.

Demonstrate an understanding of how World War II affected Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and Ned Begay.

RL.7.1, 7.3; SL.7.1, 7.6

RL.7.1, 7.2; SL.7.1, 7.4, 7.6

RL.7.1; RI.7.1, 7.3; SL.7.1, 7.6

Write an informative essay that analyzes World War II’s effect on either Ned Begay or Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. Revise the essay based on feedback.

Introduce a topic clearly, summarizing the individual’s experience.

Clearly organize ideas and use transitions (through words, phrases, or clauses) to develop the essay.

Include relevant facts, details, and quotations from the text.

Use words and ideas to show knowledge of the topic.

Write in an academic, formal style.

Provide a conclusion that builds off of and supports ideas.

Use precise and concise language. Spell correctly.

RL.7.1, 7.3; RI.7.1, 7.3; W.7.2, 7.4, 7.5, 7.9; L.7.2.b

Demonstrate understanding of academic, text-critical, and domainspecific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms. Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

L.7.6

* While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

Focusing Question 1: What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

1 “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.”

“United We Win”

“Americans All”

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about the images, text, and ideas in today’s lesson?

Examine

Why are the organization and style of an informational text important?

Identify and explain examples of the concepts of equality and marginalization in “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.” (Handout 1A).

Use the relationships among marginalization, segregation, and equality to better understand each word (L.7.5.b).

2 Code Talker, “Listen, My Grandchildren”

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about Code Talker?

3 Code Talker, Chapter 1 Organize

What is happening in Code Talker?

Identify observations and questions about the introduction to Code Talker (RL.7.1).

Analyze academic vocabulary by using context clues and morphology (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Analyze character traits of the protagonist of Code Talker (RL.7.1, RL.7.3).

Describe the character, setting, and key events in Code Talker chapter 1 (RL.7.3).

Use context and the prefix re– to analyze target vocabulary, and apply understanding in a brief response (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

4 Code Talker, pages 5–11, pages 215–218

Organize

What is happening in the Author’s Note in Code Talker?

5 Code Talker, Chapters 2–3 Organize

What is happening in Code Talker?

Examine

Why is the organization of ideas in a paragraph important?

Identify and arrange influential events in Navajo history based on the Code Talker Author’s Note (RI.7.3).

Identify key aspects of an informational paragraph (W.7.2.a, W.7.2.b, W.7.2.f).

Evaluate the impact of the words bleak, brutal, and catastrophic in context to describe Navajo experience (L.7.4.a, L.7.5.b).

Experiment

How does writing an effective topic sentence work? Examine

Why is being precise and concise important in informative writing?

Analyze how Bruchac characterizes the protagonist of Code Talker (RL.7.3).

Practice writing clear and effective topic sentences for an informative paragraph (W.7.2.a).

Examine why precise and concise writing is important in a topic sentence (L.7.3.a).

6 Code Talker, Chapters 4–5 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character, plot, and setting reveal in Code Talker?

Experiment

How does providing and elaborating on evidence in an informative paragraph work?

Experiment

How does being precise in informative writing work?

Analyze how Ned Begay’s traits influence his actions (RL.7.3).

Describe and elaborate on evidence in an informative paragraph about Ned Begay (W.7.2.b).

Build skill in writing and revising for precision through word choice (L.7.3.a).

Focusing Question 1: What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker?7 FQT SS

Code Talker, Chapters 1–5 Know

How does Code Talker build my knowledge of Navajo culture, history, and traditions?

Analyze Code Talker through a collaborative conversation with peers, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Analyze the influence of Ned’s Navajo identity on his school experience (RL.7.1, RL.7.3).

Demonstrate understanding of the meanings of and relationship between the words culture and tradition (L.7.4.d, L.7.5.b).

Focusing Question 2: How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

8 Code Talker, Chapter 6

“Pearl Harbor and World War II”

Images of Pearl Harbor headlines

Organize

What’s happening in these texts?

Experiment

How does a topic statement or sentence for a summary work?

Identify the important ideas and events of World War II and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that Bruchac develops in chapter 6.

Craft a topic statement and a summary of “Pearl Harbor and World War II” (Handout 8C) (RI.7.2, W.7.2.a).

Apply different meanings of the suffix –ism to content vocabulary, and create sentences to demonstrate understanding (L.7.4.b).

9 Code Talker, Chapters 7–8

Images of Pearl Harbor headlines

Organize

What’s happening in chapters 7 and 8?

10 “A Beautiful Dawn”

Code Talker, Chapter 9 and pages 222–223

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about chapter 9?

11 Code Talker, Chapter 10 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the events in chapter 10 reveal about the central ideas being developed in Code Talker?

12 Code Talker, Chapters 11–12 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the interactions of plot, setting, and character reveal in chapters 11–12?

Experiment

How do the structures and styles of different genres (informative vs. narrative) work?

Examine

Why is formal style important in informative writing?

Examine

Why are transitions important? Examine

Why are transitions important in writing?

Examine

Why is it important to emphasize points when speaking? Experiment

How do transitional phrases and clauses work?

Analyze how the author develops the central idea of Ned Begay’s Navajo identity (RL.7.2).

Demonstrate understanding of target vocabulary in a brief response about the module text (L.7.4, L.7.5.b).

Explore the features of different genres by adjusting writing style to a specified genre, task, and purpose (W.7.4).

Explain why using formal style is important in informative writing (L.7.3).

Determine central ideas that Bruchac develops in chapter 10 (RL.7.2).

Identify transitional phrases and clauses and explain their function in specific instances (L.7.1.a).

Analyze how the setting and plot, specifically school experiences, shape the identity of the protagonist, Ned Begay, in Code Talker (RL.7.3).

Use transitional phrases and clauses in writing (L.7.1.a).

Focusing Question 2: How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?13 NR Code Talker, Chapters 13–14 Organize What’s happening in chapters 13–14?

14 Code Talker, Chapters 15–17 Distill

What are the essential meanings of chapters 15–17?

Experiment

How does emphasizing important points when speaking work? Examine

Why are introductions and conclusions important? Examine

Why are tone and style important in an informative text?

After reading a new chapter, “The Enemies,” identify a central idea, describe the development of the central idea, analyze interactions between character and plot, and write a brief summary (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Demonstrate understanding of the multiple-meaning target word through the use of context clues, Latin affixes, and dictionaries (L.7.4).

Trace the development of a theme in chapters 15–17 (RL.7.2).

Identify the characteristics of formal tone in informative writing (L.7.3).

15 Code Talker, Chapters 18–20 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of plot, character, and setting in chapters 18–20 reveal?

Experiment

How do topic statements and evidence work? Experiment

How does being concise in informative writing work?

Develop skills in producing focused, informative writing by creating clear topic statements and adding relevant evidence to support topic statements (RL.7.1, W.7.2).

Revise a journal entry to be more concise, eliminating unnecessary words and phrases (L.7.3.a).

Focusing Question 2: How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?16 Code Talker, Chapters 21–23 Organize

What’s happening in chapters 21–23?

Experiment

How does elaborating on evidence work?

Examine

Why is correctly placing modifiers in my writing important?

Write elaboration sentences to clarify ideas and analyze evidence in an informative paragraph on battle fatigue (W.7.2.b, W.7.4).

Recognize and correct misplaced modifiers (L.7.1.c).

17 Code Talker, Chapters 24–26

Photograph of Flag Raising on Iwo Jima, 02/23/1945

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of content, style, and structure reveal in chapters 24–26?

18 Code Talker, Chapters 27–28 “Navajo Code Talkers”

Organize

What’s happening in these texts?

Examine

Why is the structure of an informative text important?

Execute

How does one use transitional phrases and clauses?

Evaluate Bruchac’s content, style, and structure in chapters 24–26 in order to gain a deeper understanding of how authors engage audiences and communicate central ideas (RL.7.2).

Distinguish between the connotations of synonyms, and rank the words to better understand their use (L.7.5.b, L.7.5.c).

Analyze central idea in Code Talker (RL.7.3).

Use transitional phrases and clauses to produce cohesive informative writing (L.7.1.a).

Focusing Question 2: How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?19 SS VOC

Code Talker, Chapter 29 Distill

What is the essential meaning of Code Talker?

How does Code Talker build my knowledge of the importance of identity and culture during times of challenge?

Execute

How do I use effective speaking and listening skills in a Socratic Seminar?

Identify central ideas in Code Talker, and discuss their development (RL.7.2).

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Demonstrate understanding of gradelevel vocabulary (L.7.6).

Execute

How do I use what I know about writing an effective paragraph to respond to Focusing Question Task 2?

Examine

Why is using varied sentence structures important when writing informative texts?

21 Code Talker Manzanar from Guard Tower

Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office School Children

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about images of Manzanar?

Excel

How do I improve my ToSEEC paragraph?

Examine

Why are subjects important when using participial phrases?

Write an informative paragraph analyzing how Ned Begay’s Navajo identity sustains him during challenging times (RL.7.1, 7.3; W.7.2, 7.4; L.7.1.a, L.7.1.c, L.7.2.b, L.7.3.a).

Explain how using varied sentence structures can influence a text’s fluency (L.7.a.b, L.5.3.a).

Evaluate to identify areas for improvement and strengthen response to Focusing Question Task 2 (W.7.5).

Formulate questions and observations about three photographs of Manzanar by Ansel Adams (SL.7.2).

Explain why subjects are important when using participial phrases (L.7.1.c).

Focusing Question 2: How does Ned’s Navajo identity provide strength during times of challenge?Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

22 Farewell to Manzanar, Chapter 1

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about chapter 1 of Farewell to Manzanar?

Examine

Why is audience awareness important?

Formulate observations and questions about Farewell to Manzanar (RI.7.1).

Explain how Wakatsuki Houston uses background information to inform her audience.

Use root and affix meanings to better understand new words (L.7.4.b, L.7.4.c).

23 Farewell to Manzanar, pages 9–13

“Relocation Camps” (Handout 23A)

Organize

What is happening in Farewell to Manzanar and the informational text “Relocation Camps”?

Examine

Why are structure and style in informative writing important? Experiment

How does using formal style and tone work?

Summarize key events that took place before, during, and after the Japanese internment (RI.7.2, W.7.10).

Describe how the style and structure of the informational text “Relocation Camps” (Handout 23A), fit its purpose and audience (W.7.2.a).

Revise a personal piece of informative writing to establish a more formal style and tone (L.7.3, L.6.3.b, L.4.3.c).

Focusing Question 3: What did the Wakatsukis experience during World War II, and how did it affect them?24 Farewell to Manzanar, Chapter 2

“World War II: Internment of Japanese Americans”

“Relocation Camps” (Handout 23A)

Organize What is happening in Farewell to Manzanar and the internment photographs?

Examine

Why are introductory paragraphs in informative essays important?

Execute

How do I use transitions in writing?

Explain how images by various photographers deepen understanding of the Japanese internment (SL.7.2).

Identify the HIT introduction structure in “Relocation Camps,” and evaluate its effectiveness (W.7.2.a).

Identify opportunities for and use transitions in an informative paragraph to produce cohesion (L.7.1.a).

25 Farewell to Manzanar, pages 21–34

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the Wakatsukis’s early days at Manzanar reveal?

26 NR Farewell to Manzanar, pages 34–41, pages 61–64

Organize What’s happening in Farewell to Manzanar?

Experiment

How does using varied sentence structures work?

Analyze the Wakatsukis’s experience of the early days of the internment (RI.7.3).

Analyze and clarify the meanings of the words subordinate, communal, and integrated and their affixes (L.7.4, L.7.5.b).

Summarize how the internment changed the Wakatsuki family unit (RI.7.2).

Use varied sentence structures to create fluency in writing (L.7.1.b, L.5.3.a).

27 Manzanar from Guard Tower Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office

School Children

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of line, shape, and value reveal in Adams’s photographs?

Analyze the elements and principles of art in Ansel Adams’s Manzanar photography (SL.7.2, W.7.10).

Use context and knowledge of the suffix –ic to explore the meaning of target vocabulary, and apply understanding of those words to art analysis (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Focusing Question 3: What did the Wakatsukis experience during World War II, and how did it affect them?28 Farewell to Manzanar, pages 71–78, ending at the end of page 78

What does a deeper exploration of the Loyalty Oath reveal in Farewell to Manzanar?

Examine

Why are style and tone important? Execute

How do I use a formal style and tone in informative writing?

Analyze the effect of the Loyalty Oath on the Wakatsukis (RI.7.3).

Rewrite an informal diary entry as a formal informative paragraph (L.7.3, L.6.3.b, L.4.3.c).

29 Farewell to Manzanar, pages 113–114, pages 142–149, pages 167–176

What are the central ideas of Farewell to Manzanar’s concluding chapters?

Experiment

How does adjusting style and tone work?

Analyze how central ideas are developed through Jeanne’s adulthood visit to Manzanar (RI.7.2).

Adjust style and tone to suit purpose and audience in a short writing piece (W.7.4).

Use the relationships among words to better apply their meaning to a paragraph about adversity (L.7.5.b).

30 SS Farewell to Manzanar

Code Talker

Know

How do Code Talker and Farewell to Manzanar build my understanding of how World War II impacted individuals?

Excel

How can I improve my speaking and listening skills in a Socratic Seminar? Experiment

How does identifying and elaborating on relevant evidence work? Experiment

How does modifier placement work?

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Analyze how two central ideas about internment are developed over the course of Farewell to Manzanar (RI.7.2).

Incorporate modifying phrases and clauses into a sample text (L.7.1.c).

Focusing Question 3: What did the Wakatsukis experience during World War II, and how did it affect them?31 FQT VOC

from Guard Tower

Roy Takeno, outside Free Press Office School Children

Distill

What are the central ideas of Farewell to Manzanar?

Execute

How do I use the ToSEEC paragraph structure to respond to Focusing Question Task 3?

Experiment

How do introductions work?

Write an informative response analyzing the development of two central ideas over the course of Farewell to Manzanar (RI.7.2, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.9).

Apply understanding of an effective introductory paragraph by drafting an introductory paragraph for an informative essay related to the Focusing Question Task topic (W.7.2.a).

Demonstrate understanding of gradelevel vocabulary (L.7.6).

Focusing Question 4: How did World War II affect individuals?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

32 EOM Farewell to Manzanar Know

How does the model build my knowledge of informative essay elements?

Examine

Why are certain elements important in writing a successful informative essay?

Experiment

How do conclusions work?

Analyze a model informative essay to identify the elements of a successful EOM Task response.

Apply understanding of an effective conclusion paragraph by drafting a conclusion paragraph for an informative essay related to the Focusing Question Task topic (W.7.2.f).

33 EOM Farewell to Manzanar

Code Talker

Know

How do the core texts build my knowledge of World War II?

Execute

How can I use evidence to support my ideas in an organized informative essay plan?

Identify and organize evidence to plan an essay demonstrating World War II’s impact on an individual from a core text (W.7.2.a, W.7.2.b).

Code Talker

35 Farewell to Manzanar

Code Talker

Know

How do the core texts build my knowledge of World War II?

Know

How do the core texts build my knowledge of World War II?

Execute

How can I use the elements of strong informative writing in my own informative essay?

Excel

How do I improve my informative essay?

How do I improve my writing to show command of English grammar, language conventions, and vocabulary?

Draft an informative essay that explains how World War II affected an individual from a core text (W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.9).

Evaluate informative essay drafts to provide peer feedback, and revise the EOM Task response (W.7.5).

Revise the EOM Task response to improve grammar and language conventions and show an understanding of module vocabulary (L.7.1, L.7.2, L.7.4).

What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker?

“United We Win” (poster) (http://witeng.link/0003)

“Americans All” (poster) (http://witeng.link/0004)

“Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.,” Alexis O’Neill (Handout 1A)

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (5 min.)

Learn (57 min.)

Examine Key Concepts (20 min.)

Notice and Wonder (22 min.)

Examine an Informational Text (15 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (3 min.)

Assign the Volume of Reading

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Marginalization, segregation, equality (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RI.7.1

Writing W.7.10

Speaking and Listening SL.7.1, SL.7.2, SL.7.6

Language L.7.5.b

MATERIALS

Handout 1A: “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.”

Identify and explain examples of the concepts of equality and marginalization in “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.” (Handout 1A).

Write a Response Journal entry explaining how one example of marginalization and one of equality from the article demonstrate the meaning of each term.

Use the relationships among marginalization, segregation, and equality to better understand each word (L.7.5.b).

Write a sentence demonstrating understanding of the words and illustrating their relationship.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION: Module 2

How did World War II affect individuals?

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–7

What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about the images, text, and ideas in today’s lesson?

CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 1

Examine: Why are the organization and style of an informational text important?

Module 2 explores a substantial Essential Question: How did World War II affect individuals? Lesson 1 builds foundational knowledge to address this question. Students explore the meaning of marginalization and contrast that with the American ideal of equality. They also get their first taste of the war’s impact on an individual: Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., commander of the Tuskegee Airmen. Students examine the structure and style of an article about Davis’s extraordinary life, taking their first steps into this module’s focus on informative writing.

Display the following images:

“United We Win” (poster) (http://witeng.link/0003)

“Americans All” (poster) (http://witeng.link/0004)

Instruct students to note what they notice and wonder about the images on a T-chart in their Response Journal. Tell students that they will return to these ideas later in the lesson.

5 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question.

Invite students to read and reflect on the meaning of the Essential Question.

n It sounds as if we’ll be reading books about World War II.

n The phrase “affect individuals” reminds me of our Essential Question from Module 1 because we looked at the effect of the social hierarchy on individuals’ identities.

Explain that students will work on fully understanding this question and the terms within it throughout this lesson.

57 MIN.

20 MIN.

Display the word marginalized, and ask students what word parts they notice. When students mention margin as a word part, have them look at the margins in a book or on a lined sheet of paper. Explain that the suffix –alized means “caused to become.”

Ask: “Putting those parts together, what do you think marginalized means?”

Provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

Word Meaning Synonyms

marginalized (v., adj.) To be excluded or treated as being of no importance. sidelined, disregarded

As needed, use the concrete demonstration of margin to deepen students’ understanding, explaining that to be marginalized means to be pushed to the margins or outside of society.

Ask: “What people or groups that we’ve read about, or that you know about, have experienced marginalization?”

Then instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What is the opposite of marginalizing people?”

n Including people is the opposite of marginalizing.

n Equality is the opposite of marginalization.

n Fairness or inclusion is the opposite of marginalization.

Provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

Word Meaning

equality (n.) A state of having the same value, measure, or quantity as something else.

Explain that the United States was founded on the ideal of equality, which made our country unique, as no other country up to the point of our founding had named equality as a goal.

Have students read an election timeline that provides historical information about citizenship voting rights for various groups: https://www.civiced.org/voting-lessons/voting-timeline. This text powerfully illustrates an example of marginalization and provides valuable context for the core texts.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What do you think you already know about World War II and the time period leading up to it?”

n I know it came after the Great Depression.

n We fought against the Nazis.

n The Holocaust happened in World War II.

n D-Day was part of World War II.

n Planes were really important to fighting World War II.

Incorporating students’ responses, and addressing any misconceptions, guide students to understand the following:

The period leading up to World War II was challenging, as the United States and the rest of the world had been suffering from the Great Depression.

Due in part to the horrors of World War I and problems afterward, many in the United States were reluctant to have America enter another world war or conflict overseas.

Several countries, including Italy, Japan, and Germany, began expanding and taking over other countries, and Japan ultimately attacked the United States. During World War II, the Nazi party in Germany targeted and killed Jews, communists, intellectuals, gays, gypsies, and others. Six million Jews were murdered, while millions of other Europeans were worked to death alongside them.

For many reasons, the United States did ultimately join the war.

To build knowledge of the events that lead to World War II, have students explore the era summaries of the Alexandria Plan. Search for History at http://greatminds.org

Have students return their attention to the images displayed in the Welcome task and share what they noticed and wondered about them.

n Both posters seem to be about fighting or war. One says, “Let’s Fight for Victory,” and the other says, “United We Win.”

n One is in both English and Spanish.

n I wondered what war it is, but now that I’ve read our Essential Question, I think it’s World War II.

n I noticed the style was kind of old-fashioned.

n I noticed that both posters show men who seem to be of different races or cultures.

n I wonder what the guys in the second image are doing.

Incorporating students’ responses, explain that the images are of posters that the United States government used to recruit people to help with America’s efforts to fight in World War II.

Ask: “What is the message of the posters?”

n The posters seem to invite all people to come fight the war.

n The posters are sending a message of equality by saying, “Americans All” and “United We Stand.”

n They are telling people that everyone is needed to fight the war, not just some.

Building upon students’ responses, clarify that the United States needed everyone’s help to fight World War II and, as a result, accepted into the military and other war efforts people from all groups. NOTICE AND WONDER 22 MIN.

Explain that students will now read about the experience of one individual who enlisted to fight in the War. Remind students that noting key details and questions is an important habit of mind and comprehension strategy to use when beginning a new text. Instruct students to make a Notice and Wonder T-Chart in their Response Journal to help them note their observations and questions about the text “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.” (Handout 1A).

Read the text aloud, pausing once or twice for students to record observations.

1 2 3 4 5

Young Davis failed the entrance exam to West Point the first time he took it. But he was “determined to succeed.” He passed it on his second try in 1932. Davis was the only black cadet at West Point. In those days, official military instructions claimed that blacks were inferior to whites and lacked courage and strong moral character. Upperclassmen at West Point wanted Davis to quit, so they enforced a “silencing” against him. For four years, no one talked to Davis. “Throughout my career at West Point and beyond, it was often difficult to reconcile the principles of Duty, Honor, and Country with the Army’s inhuman and unjust treatment of individuals on the basis of race,” Davis later said. His ability to endure the silencing made him strong. He never complained to his family, classmates, or superiors.

Davis’s graduation in 1936 made headlines. He was the first African American to graduate from West Point in the twentieth century. But when he applied to fly in the Army Air

Depending upon their prior knowledge, students may need to have several terms defined, including aviator, West Point, cadet, Corps, formation, Squadron, missions, and segregation.

Ask: “What did you notice and wonder about Benjamin O. Davis’s experience?”

n I noticed that he was the first Black man to go to West Point, but he didn’t want to be famous for that. He wanted everyone to be treated as Americans, not as part of certain groups.

n The article said that at the time, people thought Black people were “inferior to whites and lacked courage.”

n I wondered if no one really talked to him the whole time. If West Point is like a college, that would be four years of silence!

n He reached his dream of being able to fly and being in the military.

n He fought in World War II and received some kind of award.

n After the war, he also tried to fight segregation and improve the lives of African American veterans.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What experiences or examples of marginalization did you notice in the article?”

n He was the only African American graduate of West Point because, at the time, the military believed Black people were inferior and would not admit them.

n At West Point, his classmates did not speak to him because the upperclassmen wanted him to quit. The author says the silencing made him strong, but even if this is true, which I’m not sure about, giving him the silent treatment marginalized him.

n He called the army’s treatment at West Point “inhuman and unjust.”

n Even though he graduated from West Point, he was rejected for the Air Corps because he was a Black person.

Ask: “What did you notice about how Davis worked to foster more equal treatment for African Americans?”

n He was an extremely successful pilot and leader in the war despite discrimination. He helped show that African Americans were not inferior.

n After the war, he fought against segregation at home.

n After the war, his bombardment group moved to an air base that was one of the first to be run by African Americans without the supervision of white officers.

n What he wrote in his autobiography showed that he believed in equality. He did not want to be labeled as the “first black West Point graduate” but just wanted to be considered as an equal American.

Encourage students to research this extraordinary group of pilots, the Tuskegee Airmen.

Then, ask: “What did you notice about how Davis’s experiences in World War II affected him?”

n His war experiences showed him and others that he was capable of doing great things.

n He won medals for his service and went on to fight discrimination and make the army treat African Americans more equally.

n His success in the war helped him become a role model and leader.

In their Response Journal, students identify one example of marginalization and one of equality from the article, and explain how each example demonstrates the meaning of the term.

Display the Craft Question: Why are the organization and style of an informational text important?

Explain that during this module, students will develop their skills with informative writing. Explain that the article they just read is an example of such writing.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “How is the article organized?”

n The author organized it by time. She went through Benjamin Davis’s life and told about the main events that happened to him.

n The paragraphs were each pretty short and focused on one big event or idea.

n The opening paragraph was a little more personal and told about why the rest of the article happened.

n The last paragraph summed up the article.

Ask: “How did this organization help you as readers?”

n It was easy to follow.

n The first paragraph got me interested, and then the others provided information that was very interesting about him.

n One paragraph easily led to another, which made me interested and able to understand it.

Direct students to focus on the first paragraph. Ask: “What do you think the author’s purpose was in beginning the article this way?”

n The author wants the reader to become interested in learning more about Davis right away, and the first sentence about how his life was changed forever makes you want to find out how and why.

n She wants the reader to understand why Davis was willing to put up with mistreatment and persevere. She shows how he fell in love with flying and became determined to become a pilot.

n The author wants the reader to relate to Davis, so she includes a quotation that makes him seem like an ordinary person.

Then direct students’ attention to the conclusion. Ask: “What is the effect on you as a reader of the author ending the article in this way?”

n It is inspirational and makes me want to know more about him.

n It sums up the big picture of why his story matters.

n It tells about the main idea of his life without repeating the facts.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What do you notice about the style of writing? How does it compare to the narrative writing you did in the first module?”

n It is more to the point and doesn’t have so much description or sensory details.

n It focuses mainly on facts, not on his feelings or thoughts. When it does discuss his feelings or thoughts, it uses quotations from him.

n It is very organized and moves from one point to the next. Narrative sometimes is not so streamlined.

Build on student responses to explain that when writing informative essays, students should, like this author, maintain a formal, not conversational style. Ask: “How does this author manage to be both formal and engaging at the same time?”

n She chooses interesting facts.

n She puts quotations in that make it easier to relate to Davis.

n She doesn’t put too many facts in. Some articles overwhelm you with facts, but she really gets to the point.

Land5 MIN.

Have students write in their Response Journal in response to the following prompt: “How does the story of Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. help to start to answer the Essential Question: How did World War II affect individuals?”

Invite students to share responses as time permits.

Distribute and review the list of additional texts from Appendix D: Volume of Reading, and the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions. Explain that the list contains books with further information about topics discussed in the module. Tell students that they should consider the reflection questions as they independently read any additional texts and respond to them when they finish a text.

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal, or submit them directly. The questions can also be used as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide (http://witeng.link/IG) for a further explanation of Volume of Reading, as well as various ways of using the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions.

To complete the CFU, students must cite textual evidence that exemplifies the concepts of marginalization and equality. Check for the following success criteria:

Cites textual evidence to illustrate the concept of marginalization

Cites textual evidence to illustrate the concept of equality.

The concepts of marginalization and equality are useful background information as students explore the impact of World War II, in America and abroad. If students struggle to understand the two concepts, ask them to sort examples of marginalization and equality, using a series of historical events, such as the ratification of the 19th amendment, the Emancipation Proclamation, etc.

Time: 15 min.

Text: “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.,” Alexis O’Neill (Handout 1A)

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Use the relationships among marginalization, segregation, and equality to better understand each word (L.7.5.b).

TEACHER NOTE

The Module 2 Assessment Pack contains two direct vocabulary assessment tools and corresponding directions to be administered during Deep Dives 19 and 31. Consider using these tools to preassess students at the start of this module. Do not share results with students, but use the data to inform and differentiate vocabulary instruction throughout the module. At the close of the module, reassess students using the same tool to determine their growth against the baseline data.

Also consider distributing the list of words to be directly assessed so that students will know which words they will be held accountable for and can begin studying. Directly assessed words are noted in Appendix B.

Launch

Display the following words explored in the core lesson:

marginalization equality

Provide the following definition for students to record in their Vocabulary Journal.

Word Meaning

segregation (n.)

Separating or isolating certain groups based on their race, class, or ethnic origin.

Synonyms

isolation, exclusion

Ask students to examine the definition—as well as those for marginalized and equality, which they recorded in the core lesson—and underline key words in the definitions that are important to understanding the words. Have students work in pairs to paraphrase the definitions.

Call on two or three pairs per word to share their paraphrased definitions, guiding and refining students’ work as needed.

TEACHER NOTE

As students work, observe the words they underline. As time permits, talk with students individually about their decisions in order to assess students’ understanding of the words and of the process of selecting key words.

Explain that, like people, words have interesting and complex relationships to one another. Tell students that they will determine the relationships among the three words they just studied and then create a visual representation of that relationship.

Ask: “What types of relationships can words have to one another?”

As students share ideas, record their responses to serve as reminders for others during the activity that follows.

n Words can have the same parts, such as a suffix or prefix.

n One word could mean something similar to the other one.

n A word could be the opposite of another word.

n A word could help define another word.

n Words could be the same part of speech.

Instruct each pair to join with another pair, forming groups of four.

Tell students to work in their group to create a relationship map, which is a web, diagram, or other visual display that shows the relationship between words. Encourage students to revisit the underlined portions of the definitions, and to brainstorm ideas as a group before beginning.

If students have difficulty generating ideas, sketch a few examples, such as a continuum line with “negative” words at one end and “positive” words at the other; a concept web, with a word listed in the center and equal and unequal words extending from it in spokes; a picture, using human figures or facial expressions with the words listed; or a visual definition for each word that uses a similar image to connect the words.

Have students display their relationship maps and view at least two other groups’ maps.

For this exercise, there are no right or wrong answers. Instead, the thinking students display as they explain their maps is what is important. Accordingly, as students work on their relationship maps, circulate and ask them to explain their choices. Prompt students toward deeper thinking with probing, openended questions (e.g., Why did you …? What if ...? How could you …?).

Using their own experiences or the article from Handout 1A, students write a sentence or two to show their understanding of the words and their relationship.

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (2 min.)

Learn (60 min.)

Examine Listening Barriers (10 min.)

Notice and Wonder (25 min.)

Research Topics of Interest (25 min.)

Land (7 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (1 min.)

Look Ahead

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Sacred and the Morpheme sacr (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

Reading

RL.7.1

Writing W.7.7, W.7.8, W.7.10

Speaking and Listening SL.7.1, SL.7.2, SL.7.6

Language

L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b

Handout 2A: Sacred and the Morpheme sacr

Identify observations and questions about the introduction to Code Talker (RL.7.1).

Complete a Notice and Wonder T-Chart with key details and questions about the text.

Analyze academic vocabulary by using context clues and morphology (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

Complete Handout 2A, defining sacred, using it in a sentence, and analyzing the root of the word.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–7

What does being Navajo mean to the protagonist of Code Talker?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about Code Talker?

Students read “Listen, My Grandchildren,” the moving introduction to Joseph Bruchac’s novel Code Talker. They notice and wonder about the text, which provides insights to some of the many themes ahead, including the importance of the protagonist’s identity as a Navajo and a World War II code talker.

5 MIN.

Have pairs discuss the most important and interesting knowledge and skills they developed in Module 1, including knowledge of the Middle Ages, identity development, historical fiction, and narrative elements.

2 MIN.

Post the Focusing Question and Content Framing Question.

Remind students of the concepts they discussed in Lesson 1—that throughout history, societies segregate and marginalize groups, but societies also make strides toward equality. Explain that today, students will begin a text, Code Talker by Joseph Bruchac, that will allow them to more fully explore these concepts, as well as deepen and extend the understanding of historical fiction and narrative elements that they developed in the first module.

Explain that throughout this module, students will focus on how to become more effective listeners, as they listen to texts like the one they will begin in this lesson, instruction, or classmates in discussions.

Tell students that to begin considering their listening habits, they will play a quick game called “Me, Too.” Explain that if a statement you read is true for students, they should stand up and say, “Me, too!” and that they should stay standing until you read a statement that is not true of them. Read aloud the following statements, one at a time, pausing after each for students to reflect on whether it is true for them and respond accordingly:

Sometimes I tune out when someone else is talking.

Sometimes I look like I am listening, but really, I am not.

I rarely lose focus when listening.

Sometimes I think I listened to the teacher or a classmate, but when I try to remember what was said or answer a question about it, I realize I didn’t hear what they said.

I carefully listen to everyone who talks to me.

I listen better to some people than to other people.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What helps you listen well, and what are some barriers, or things that can get in the way, of your listening?”

n Sometimes you’re distracted because you’re thinking or worried about something else.

n It can be hard to listen to some people because they talk too much or are monotone.

n It helps me listen if I really am interested in what the other person is saying.

n Sometimes I am listening, but the person says something that makes my brain go off in another direction.

If students do not mention it, ask: “Why is it harder to listen to some people than to others?”

n Some people speak softly.

n Some people make their points more clearly than other people.

n Some people can be really hard to understand.

Then ask: “What problems result from not listening in class?”

n You can miss important information a teacher is giving.

n You can misunderstand someone’s point, which can lead to confusion or arguments.

n It can be embarrassing when the other person catches you not listening.

Tell students that in this lesson, as they listen to a new text being read aloud and discuss it with classmates, they should consider what helps them listen well and what impedes their listening.

25 MIN.

Ask students to examine Code Talker’s front cover, and ask: “What do you notice and wonder about the front cover?”

n The title and author’s name are listed on a chain, kind of like a necklace.

n I think people in the army wear things like that called “dog tags.”

n It says it’s a novel, so I think it’s not true, but it also says it’s about the “Navajo Marines of World War II,” so I am thinking it might be based on the truth.

n Maybe it is historical fiction like The Midwife’s Apprentice

Instruct students to create a Notice and Wonder T-Chart in their Response Journal, and explain that as they listen to you read the text aloud, they should follow along in their own texts and consider what they notice and wonder.

After each pause in the Read Aloud, students identify and record key details and questions about the book.

Read aloud the first paragraph. After giving students time to record what they notice and wonder, instruct them to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice and wonder as you listened to the first paragraph?”

n The narrator seems to be talking to his grandchildren about a medal he won in a war.

n He says that he was not allowed to tell the story for “many winters.” I wonder why not.

n It says it’s a true story about how Navajo Marines helped America win a war, but the front of the book says it’s a novel. So, I think we were right that it’s a novel based on true events. I wonder if he is Navajo.

n He says he was trained with some other men. Trained for what, I wonder?

n Why did the lives of many men depend upon his and the other men’s memories?

Code Talker contains many Navajo words and names that may be difficult to read aloud. Before continuing reading, explain that it is possible to unintentionally mispronounce or put the wrong emphasis on certain syllables of words. Reassure students that they should simply do their best when they read the text. Do the same when reading aloud, striving to read words correctly during the Read Aloud but also modeling fluent reading.

There are many tutorials and audio pronunciation guides for the Navajo language online.

Read aloud the next paragraph, and then pause for students to note what they noticed and wondered. Ask: “What did you notice in this paragraph?”

n The back of the medal has a man riding a horse. He is a Pima Indian.

n The man telling the story knew the man on the medal.

n He says that Ira Hayes was not one of “our people,” but a Pima Indian. That makes me think we were right that the man telling this is a Navajo.

n They fought on an island far off in the Pacific Ocean.

n People got hurt in the battles.

Then ask: “What are you wondering about so far?”

n How could the man on the medal both be on a horse and be raising a flag?

n Why are some words in italics?

n What is a .25 caliber rifle?

n What does the “thumping of mortars” mean?

As students share their questions, address those or invite students to do so as necessary to understand the text. However, let students know that the book itself will address many of their questions, so it is fine for them to keep wondering about some of them.

Read aloud page 2, stopping before the last paragraph on the page, which begins, “But I am getting ahead of myself.”

Give students time to record what they notice and wonder. Instruct them to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice in this section of the text?”

n There was a terrible battle.

n They were going up a mountain.

n When they got to the top, they raised a flag.

n The words in italics seem to be Navajo words. He uses “we” about Navajo names, so I definitely think he is Navajo.

n The narrator did not go up to the top but helped in some other way.

n He helped send some kind of message.

n They seem to like to name things. That reminded me of The Canterbury Tales and also makes me think it might be about identity.

If students have not yet brought up the issue, ask: “What have you noticed and wondered about the author’s use of italics?”

Then ask: “What are you wondering about so far?”

n Whose flag was it that they raised?

n Why does he call the United States “a sacred land”?

n What does he mean by “bilagáanaa names”?

n What does he mean that the land “sustains us”?

n I wonder why they used “Sheep Pain” for Spain. I didn’t get that.

Again, pause for students to consider others’ questions, and address misunderstandings or necessary questions. For example, if needed, help students understand the wordplay in using “Sheep Pain” for Spain. Also, if students do not bring up the word sacred on their own, briefly point it out and discuss what students already know about the American Indian beliefs of the land as being sacred, or holy, and that all living things that grow or live off the land are connected.

Continue reading from the bottom of page 2 through to the end of the introduction. After students have had time to record what they notice and wonder, ask what they noticed in this last section of the introduction.

n Somehow being able to speak Navajo helped in the war.

n Someone tried to beat the Navajo language out of him when he was a child.

n He was a code talker, but I am not sure what that means yet.

n He is not going to start the story with the war but will get to it later.

n I am wondering if this book is about identity, too. I think it might be because this secret and the war seem really important to who he is now.

Then ask students about any questions the text raised.

n Who tried to beat the Navajo language out of them, and why?

n What was the secret?

n Why couldn’t they tell their families the secret until long after the war ended?

n What does the part about setting up a loom mean?

TEACHER NOTE The Deep Dive for this lesson provides an opportunity for a deeper exploration of the word sacred and its root, sacr.If students have not yet brought it up, ask: “What did you notice about the way the story is being told? How is it similar to or different from the other books we read, and what difference does it make to the story?”

n It is a grandfather telling a story to his grandchildren. It seems personal and real.

n The last two books we read, The Canterbury Tales and The Midwife’s Apprentice, were written in the third person, but this is more like Castle Diary because it is told in the first person.

Ask students to reread the chapter, annotating places in which the narrator directly addresses his grandchildren: “Grandchildren, you asked me about this medal of mine” (1); “Look here” (1); “he was not one of our people” (1); “But I am getting ahead of myself” (2).

Then ask: “How did you do as a listener today? Did you face any listening barriers while listening to and talking about the book, and if so, how did those affect your learning?”

n Sometimes when my partner was talking, I was thinking about what I would say next instead of listening.

n I got very interested in the italicized words and how to read those, and I suddenly realized I didn’t listen to the next paragraph.

Encourage students to continue thinking about their listening strengths and challenges, as well as any barriers and how they can overcome those.

25 MIN.

Explain that to gain helpful background information to understand the book Code Talker, students will do some research about a topic of their choice. Present the following topic choices:

What is known about the Navajo language, and how does its pronunciation work?

What kind of weaponry was used in World War II, and what are some of the weapons and artillery described in Code Talker, such as caliber, rifles, shells, mortars, and machine guns?

What are the traditional dress and jewelry of the Navajos?