changing moral laws

Changing Moral Laws Stewart W. Miner, PGM Grand Secretary Emeritus

A

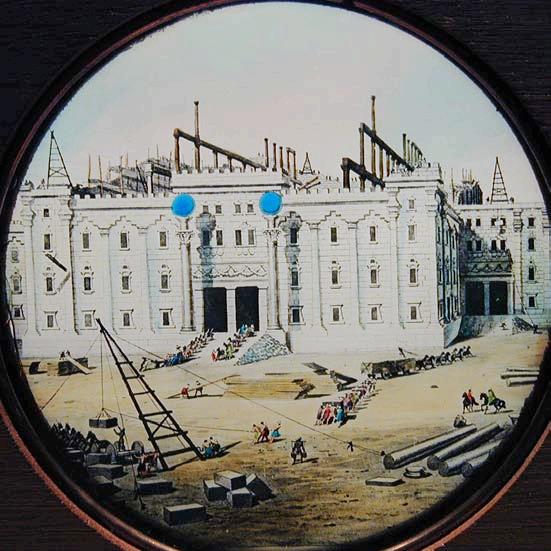

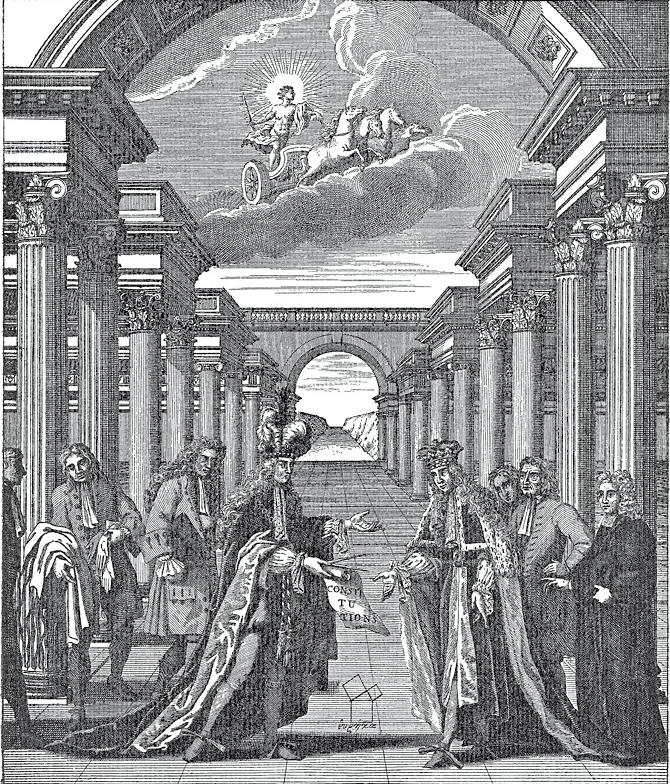

t the time of his installation every Master-elect signifies his agreement with a specific number of charges and regulations that pertain to the duties of the exalted office that he is about to enter. At that time he, like all Masters before him, agrees to be a good man and true, and in so doing, to obey the moral law, a nebulous statute which is as broad as time, and one that has provided the foundation of Masonry’s work in all ages. By so doing he is caused to contemplate his role, and that of his lodge and his brethren, in a world-wide secular society wherein challenges to the norms of reason are now commonplace. Life is not now, nor has it ever been, perfect, and in addressing that truth, in a constructive fashion, for the purpose of strengthening our institutional will to overcome evil by good, it seems appropriate to critically examine our concepts of moral law and to determine, if possible, how and in what fashion the Craft may best serve humanity. To that end it may be fruitful to look at the philosophical foundations of Masonic morality, to review the demands that the fraternity makes upon its adherents, and finally, through a review of current developments in society universal, to assess how Masonic morality impacts on society as a whole. Such an appreciation, in a time of rapid and unbridled change, is clearly in the interest of the Craft. Let us begin by defining morality, a nebulous term at best. Many years ago J.E. Morgan, wrote in the Journal of the National Education Association that the concept of morality refers to the “standards of conduct set by people of influence or authority.” Morgan also notes that “superficially, moral patterns differ somewhat from country to country and from one period to another, but fundamentally they rest on basic human needs,” which he suggests are four in number — honesty, industry, self reliance, and cooperation. In another source, the Master’s Lectures as delivered in Evans Lodge No. 524 in Illinois, it is written that the word morality is derived from a Latin word meaning “custom.” This source goes on to state that the

The Voice of Freemasonry

16

word was probably used by the Romans to denote the concept of “living according to custom.” To this those of the Christian religion added a new concept whereby the term was shaped to denote the “life of the righteous,” a concept that is advanced in this source as follows: “It (righteousness) is living the right way, doing the right things, thinking the right thoughts. But what is right? That question may be answered in two ways: it might be said that the right way is that which gives us the fullest, completest [sic] life, for it is the purpose of morality to give life and give it more abundantly; or it might be said that right is conformity to the law of being. As the scientist seeks to learn the laws of nature and to conform to them, so does a righteous man seek to discover the laws of his own nature in order to conform to them; he obeys the laws of the body by living cleanly and simply, he obeys the laws of the intellect by thinking facts without prejudice or haste, and he obeys the laws of the heart by loving only that which he finds to be good and true.” These commentaries on righteousness, while undeniably useful are not entirely sufficient, however, to indicate how the Craft has traditionally defined its concepts of morality. Furthermore, they do not necessarily infer how those concepts are implemented by either the Lodge or the individual Mason. Masonry, at least in the Grand Lodge era, has been very circumspect in discussing its conception of “the moral Law,” apparently preferring ambiguity to specificity. On this score we are forced to be content with generalities such as those that are exemplified by the general charges of a Freemason. If the official documents of modern Masonry fail to publicly position the Craft in definitive terms, a number of Masonic scholars have filled the vacuum thus created. Albert Mackey in his work on jurisprudence, for example, states that the moral law “denotes the rule of good and evil, of right and wrong, revealed by the Creator and inscribed on man’s conscience, even at his creation, and consequently (is) binding by divine authority.”