Field Guide #1

Defining Public Life In San José

Developed by Gehl in partnership with the City of San José and with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

January 2019

How to use the San José Public Life Field Guides

In DEFINING Public Life you will learn the tangible benefits that a diverse, inclusive and vibrant Public Life can offer to our city.

This guide introduces San José’s Vision and Framework for advancing Public Life as a strategic city driver.

MEASURING Public Life provides an overview of the methods used by government agencies and civic organizations around the globe to monitor Public Life targets. This guide also provides recommendations for San José’s data collection initiatives.

NURTURING Public Life illustrates the progress that our city has made in promoting Public Life, and presents practical actions that city agencies and Community Partners can take to further advance the goal of connecting San Joseans to their public spaces.

Key takeaways from Defining Public Life

Public Life is what happens in the public spaces of our cities. It’s what a group of people create when they spend time together outside their homes, offices and cars. (p. 5)

Public Life is everyday. Daily dog walking is just as much a part of a vibrant Public Life as taking the family to the annual Rose, White and Blue parade. (p. 7)

1 2 3 4 5

San José has a vision for Public Life: “The City of San José connects people to people and people to places. We invite all residents to create and participate in everyday experiences in public space, fostering community cohesion across neighborhoods.” (p. 27)

Planning, public space design and activation are the mutually reinforcing components of San José’s guiding framework to foster robust Public Life. (p. 31)

Cities with robust Public Life attract and connect people. Public Life fosters a host of tangible benefits that support broader city goals. (p. 9)

What is Public Life?

Public Life noun

Gehl Institute Mayor’s Guide to Public Life“Public Life is what people create when they connect with each other in public spaces — the streets, plazas, parks and city spaces between buildings. Public Life is about the everyday activities that people naturally take part in when they spend time with each other outside their homes, workplaces and cars.”

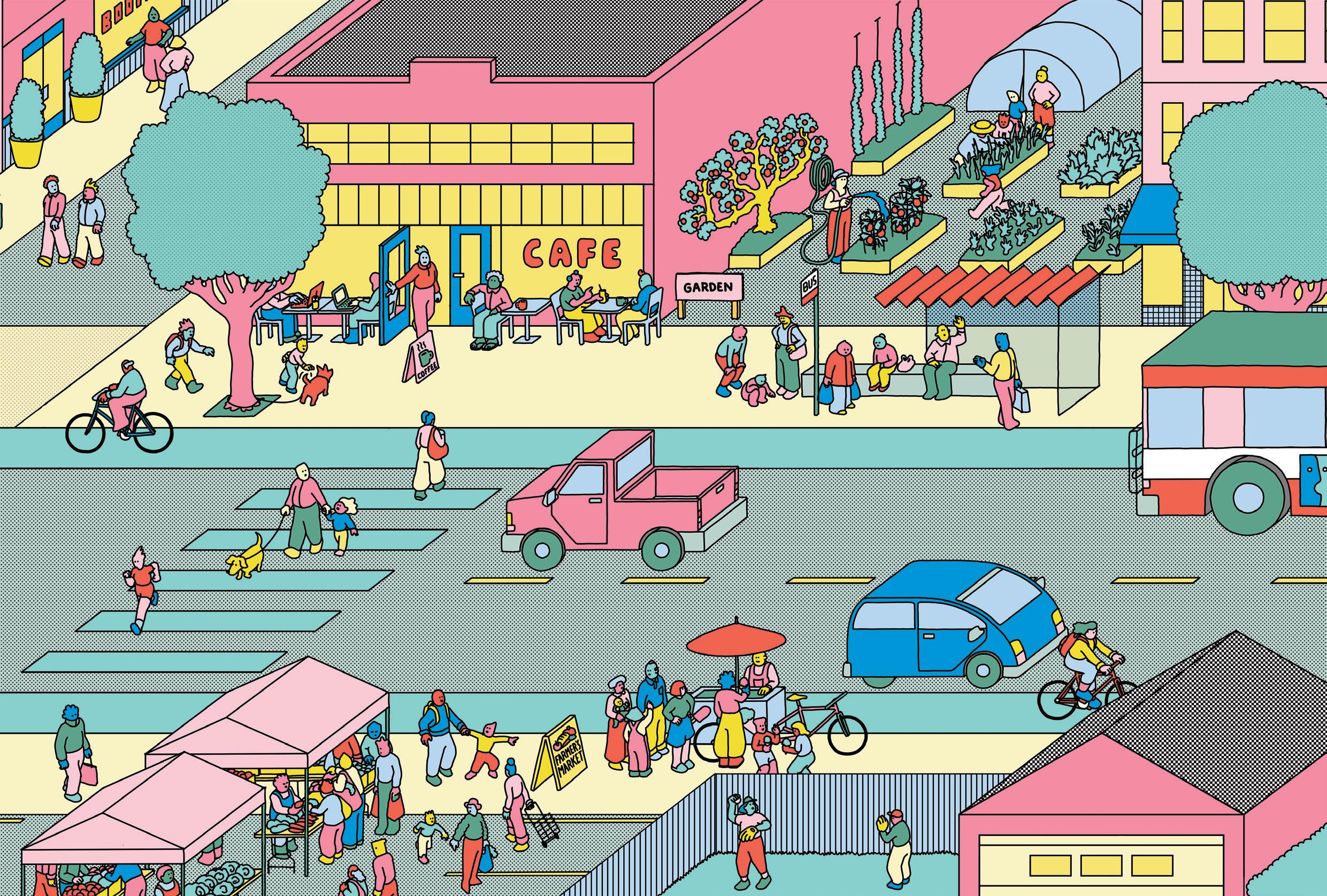

Regular public events that fit into daily life imbue a place with a sense of purpose, and give people a reason to stay and discover more about the area. Food, shade, and the presence of other people never fail to attract a crowd at this outdoor market.

Farmer’s Market

Farmer’s Market

What does Public Life Look Like in San José?

Public Life is the everyday experience of being in public space.

People often think about Public Life in terms of large organized public events, but it's much more than special events. Public Life at its heart is everyday activities: walking down the street with others, the spontaneous visit to a park, or the serendipitous encounter with neighbors at a corner store.

IT’S

IT’S WAITING FOR PUBLIC TRANSIT

IT’S

IT’S SHARING TRADITIONS FROM SAN JOSÉ'S

COMMUTING ALONG THE GUADALUPE RIVER TRAIL

DIVERSE COMMUNITY

IT’S WATCHING A STREET PERFORMANCE

IT’S CATCHING UP WITH FRIENDS AT THE SAN PEDRO SQUARE MARKET

IT’S HANGING OUT AT THE SOFA STREET FAIR

IT’S SKATEBOARDING AT LAKE CUNNINGHAM REGIONAL SKATE PARK

COMMUTING ALONG THE GUADALUPE RIVER TRAIL

DIVERSE COMMUNITY

IT’S WATCHING A STREET PERFORMANCE

IT’S CATCHING UP WITH FRIENDS AT THE SAN PEDRO SQUARE MARKET

IT’S HANGING OUT AT THE SOFA STREET FAIR

IT’S SKATEBOARDING AT LAKE CUNNINGHAM REGIONAL SKATE PARK

DOES A CITY NEED PUBLIC LIFE?

Making Public Life a central driver of decisionmaking pays dividends across the board.

More than ‘nice to have’, fostering a robust Public Life produces a ripple effect of tangible individual, neighborhood, and citywide benefits. A robust Public Life is key to achieving San José’s potential as a new kind of successful city — one with a sustained sense of community, high social capital, social mobility and social cohesion.

A vibrant Public Life is an indicator of a city that is successful in an economic, social and environmental sense. Places that encourage people to walk, bike and spend time on the streets also have residents that are happier, healthier and more connected. In recent years, employers have discovered that locating in cities with thriving Public Life is essential to attract and retain talent.

City government can’t do it alone! A great Public Life requires the participation of a wide range of community stakeholders

“San José needs public spaces that generate opportunities for people to engage.”

— Mayor Sam Liccardo

Public Life Co-Benefits

San José has already begun to use Public Life as a lens through which to understand city planning and as a metric of success.

Seven categories of cobenefits are described in the following pages.

PUBLIC SAFETY

MENTAL HEALTH

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

PHYSICAL HEALTH

CITY IDENTITY

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

SOCIAL COHESION

Guiding Values from San José's General Plan

Envision San José 2040 is the city’s blueprint for responsible growth, articulated through a series of strategies and grounded in seven community crafted values. These shared values support Public Life.

These plans are already about Public Life! A Public Life lens also helps us accomplish what these plans require.

Innovative Economy

Vibrant Public Life supports each of these planning values!

Environmental Leadership

Diversity and Social Equity

Interconnected City

Healthy Neighborhoods

Quality Education and Services

Vibrant Arts and Culture

“ This requires a significant change to how cities plan; it pivots from one that is City-centric into one that is people-focused.”

— Climate Smart San José “ Densifying our city in focused growth areas increases walkability and cycling and also makes our neighborhoods more vibrant, distinctive, and enjoyable.”

— Climate Smart San José

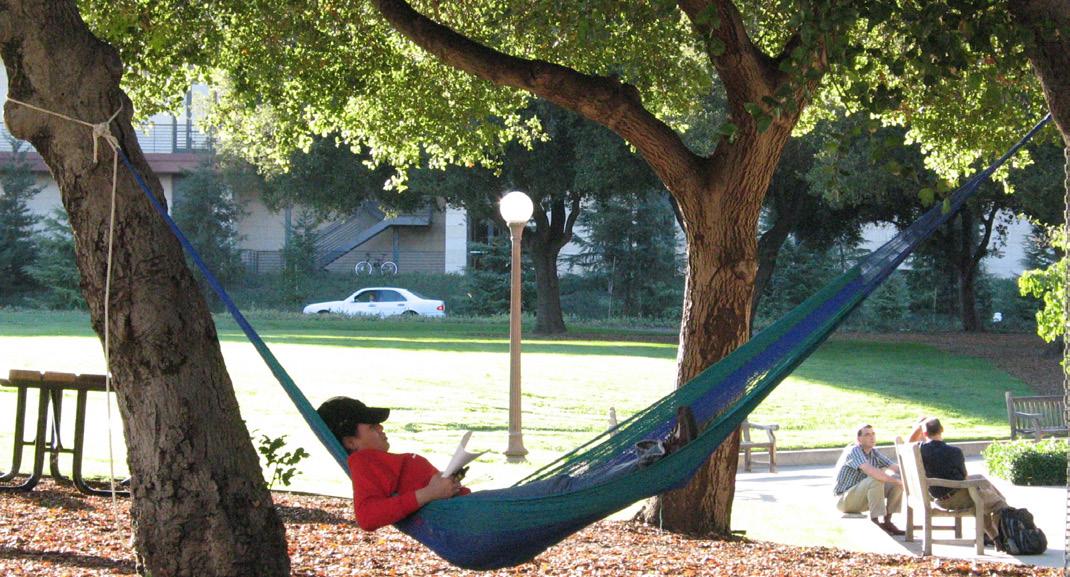

Staying healthy can be a walk in the park for San Joseans who can make walking a part of their daily routine. Promoting compact neighborhoods that meet daily needs can reduce preventable diseases caused by inactivity.

90 minutes of physical activity built into your routine can be achieved through urban design alone.

1.“Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study.” James F Sallis, Jens Troelsen, et al.

“How do we get people out? We are looking at how the built environment gives clues that encourage people to walk.”

— Salvador Álvarez

Downtown Coordinator, Office of Economic Development

Physical Health

Active lifestyles support personal wellbeing. Encouraging people to use public transit, walk and bike can contribute to improved physical and mental health.

144 hours

is the average amount of time a San José driver spends each year sitting in traffic.

“Climate Smart San José: A People Centered Plan for a low carbon city.” City of San José

Living in walkable neighborhoods reduces risk of asthma, diabetes and hypertension.

Public transit users are more likely to meet recommended daily physical activity.

“Changes in Neighborhood Walking Related to Changes in Perceptions of Environmental Attributes.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine

That's 24 minutes per day. If that time sitting in traffic was replaced by a brisk walk, each person would surpass their recommended aerobic activity.

150 minutes

of moderate aerobic activity weekly are recommended for adults to stay healthy.

CDC Healthy Places Toolkit 2015, The Center for Disease Control

Mental Health

Removing an hour from your commute produces the equivalent happiness of a 40%

pay increase.

“The Stress That Doesn’t Pay: The Commuting Paradox”, Stutzer and Frey.

Elders who live in walkable, connected neighborhoods show fewer declines in mental acuity and Alzheimer’s-related cognitive functions.

“Neighborhood Integration and Connectivity Predict Cognitive Performance and Decline”

Watts, A. et al

Increased risk of early mortality among the socially isolated.

“Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality”,Holt-Lunstad, J. et al.

Since the 1980s, the percentage of American adults who say they’re lonely has doubled from 20% to 40%.

“Loneliness among Older Adults: A National Survey of Adults 45+” Wilson, C. & Moulton, B.

Active Public Life nurtures sociability and social connections, which are correlated with mental health and longevity.

Parks and other public spaces provide opportunities for people of all ages to connect and socialize.

A place to play and make new friends makes interactions easy and frequent, decreasing the risk of social isolation.

“Public Life enhances the health of the community by reducing social isolation for seniors and providing places for people to gather and connect. This type of connection and the health benefits it provides is central to the mission of PRNS.”

— Nicolle Burnham

Deputy Director, Capital Programs, Department of Parks, Recreation & Neighborhood Services

Social equity + community cohesion

Routine exposure to people of different backgrounds, though initially jarring for some, can diminish prejudice and foster attitudes of inclusion in the long run.

An age-friendly city should facilitate social relationships through local services and in the activities that bring together people of all ages.

“Global age-friendly cities : a guide” World Health Organization

It is the presence of a group that is proximate, yet segregated — close but far — that precipitates the politics of division.

“The Effect of Segregation on Intergroup Relations” Enos, R. & Celaya, C.

More prolonged contact or interpersonal interaction can diminish initial exclusionary impulse in diverse groups.

“Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes.” Enos, R.

In cities with higher public transit and walking levels, lower levels of aggressive driving death rates were predicted.

“Once There Were Greenfields: How Urban Sprawl is Undermining America’s Environment, Economy, and Social Fabric” Benfield, K., Raimi, M. & Chen, D.

High economic mobility is correlated with areas with less residential segregation, less income inequality, better primary schools, greater social capital, and greater family stability.

“Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States.” Chetty, R.; Hendren, N.; Kline P. & Saez, E.

Public transportation can be a force for good by diminishing prejudices between disparate ethnic groups.

“Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes.” Enos, R.

“Streets are the primary public space of our daily life. We should design streets for people’s needs. Streets build our sense of community.”

—Jim Ortbal Deputy City Manager of San José

People feel happy, comfortable and safe where they can see and be seen by others. Public Life happens at the scale of human sight.

“The presence of a vibrant Public Life is an indicator of healthy community. When people are out and about in the public it creates a virtuous cycle to invite more social, physical and economic activity.

— Salvador Alvarez Business Development Officer

public safety + sense of security

Neighborhoods with stronger walkability indices are associated with decreased property crime, murders and violent crime.

”Does walkability matter? An examination of walkability’s impact on housing values, foreclosures and crime” Gilderbloom, J. et al.

Businesses with longer open hours and higher foot traffic are associated with lower crime on the block.

People living in walkable neighborhoods trust their neighbors more, participate in community projects and volunteer more than those in less walkable areas.

“Examining Walkability and Social Capital as Indicators of Quality of Life at the Municipal and Neighborhood Scales.” Rogers, Shannon H. et al

The best thing for safety is to have parks and public spaces that are very well used by all.“Analysis of Urban Vibrancy and Safety in Philadelphia” Humphrey, C. et al

City Identity

Public Life attaches people to places, builds emotional connections, and increases residents’ identification with the place in which they live.

People’s pride and loyalty to their communities are strongly correlated to the availability of social/ cultural events, places to meet people and vibrant nightlife.

“Knight Soul of the Community 2010; Why People Love Where They Live and Why it Matters: A National Perspective” Knight Foundation/Gallup

Communities’ social offerings, openness, and aesthetics are, in that order, most likely to influence residents’ attachment to their communities.

“Knight Soul of the Community 2010; Why People Love Where They Live and Why it Matters: A National Perspective” Knight Foundation/Gallup

San José is one of the nation’s most diverse cities. It has the opportunity to leverage on its unique identity by showcasing and celebrating its cultural richness.

Viva CalleSJ transforms San José’s streets into one of the largest shared open spaces in the region. People of all ages, abilities, and social, economic and cultural backgrounds come together and enjoy recreational activities, social services, and cultural demonstrations.

“Public Life is about making an interesting, vibrant and welcoming city... a place where more people will want to live and work.”

— Blage Zelalich Downtown Manager, Office of Economic Development

JoséDepartment of Transportation

San José has over 53 miles of trails and over 200 miles of on-street bikeways connecting residential neighborhoods to places of recreation and work. The increase in the use of these amenities shows that people are ready and willing to make active transportation a part of living the good life.

“Thriving Public Life closer to where people live reduces transportation demand. The most efficient forms of transportation lead people to have more public interactions.”

— Doug Moody

Associate Engineer

Environmental Sustainability

The Good Life 1.0 was about consumption and sprawl. The Good Life 2.0 is about having time to enjoy your life and being able to accommodate a healthy lifestyle into your routine. Compact development can help deliver the Good Life 2.0. Co-benefits include lower cost of infrastructure provision, increased efficiency, reduced traffic congestion and transit times, and increased usage of low-carbon transport modes.

“Climate Smart San José: A People Centered Plan for a low carbon city.” City of

Sprawl

Sprawl

Transportation now tops power generation as the top source of US CO2 emissions. Urban transportation and urban form can make a significant difference in reaching climate goals. Public Life is a key feature of "The Good Life 2.0".

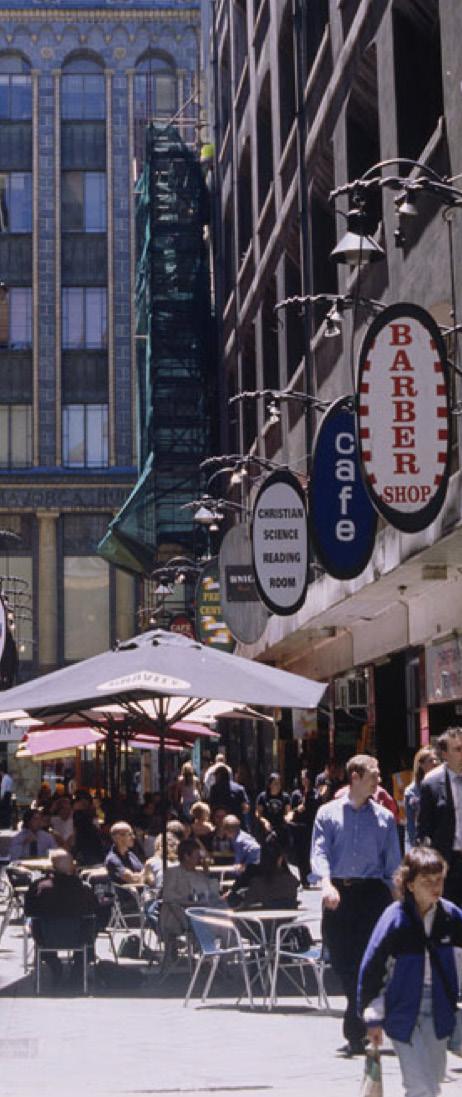

Economic Development

Shoppers arriving on foot, by transit or by bike tend to spend similar or slightly less at businesses per visit, but they visit them more frequently, spending more per month.

Higher walkability ratings are associated with higher residential values and commercial rents.

“The Walkability Premium in Commercial Real Estate Investments” Real Estate Economics

After the 2008 real estate collapse, homes in walkable urban neighborhoods experienced less than half the average decline in price from the housing peak in the mid2000s.

“What do the Best Entrepreneurs want in a City” Endeavor Insights

Attractive and memorable places become selfreinforcing, drawing new investment and sustaining long-term value.

Quality of life considerations (access to nature or local cultural attractions) are extremely important factors in attracting and retaining knowledge workers and entrepreneurs to cities.“Consumer Behavior and Travel Choices: A Focus on Cyclists and Pedestrians” NACTO

San José offers more than 100 neighborhood and regional parks, many of which have not been discovered by its residents. Getting people to explore them increases satisfaction and community pride for current and future residents.

Homebuyers and businesses favor walkable, amenity-rich environments that offer opportunities for an active and connected lifestyle. Companies are looking for these qualities when choosing places to invest in.

“The demand to create a Public Life agenda is imperative to support and attract businesses, showcase our cultural richness and vibrancy.”

— Tammy Turnipseed Events Director of the Office of Cultural Affairs

SAN JOSé’s VISION FOR Public Life

San José’s vision for Public Life is a shared lens through which departments should look at their programs and projects.

The VISION

The City of San José 1 connects people to people and people to places. We invite residents to create and participate in 2 everyday experiences in public space, 3 fostering community cohesion 4 across neighborhoods.

Five dimensions of San José’s Public Life

connects people to people and people to places

Good urban design matters. San José’s public realm enables and dignifies the Public Life of the city, both at destinations and in between them. Every place is an opportunity to make Public Life thrive.

1 2 3 4

fostering community cohesion

Flexible and open, San José’s Public Life will reflect the city’s diversity, inviting those from all backgrounds to spend time together, and fostering an enriched sense of community cohesion.

everyday experiences

Public Life reinforces San José’s strategic goals, generating a range of positive everyday experiences that benefit residents’ mental and physical health, economic development, safety, happiness, equity and opportunity.

across neighborhoods

San José’s vibrant Public Life is expressed distinctively in each neighborhood and district. It enriches all places on the urban-suburban continuum.

THE Framework

Planning, public space design and public space activation are the mutually reinforcing components of San José’s Public Life Framework.

It is difficult to sustain Public Life by focusing on isolated activities that are not part of a larger, cohesive plan. Conversely, a strong plan can fail to deliver results if its individual projects are not executed in a way that is sensitive to the design traits and activities that attract people.

By having Public Life as a common objective multiple city departments and Community Partners demonstrate they are working together to achieve the city’s vision.

LIFE

Three Public Life Focus Areas

City Planning

The following planning documents set public policy goals and guidelines that support Public Life:

• Envision 2040 Plan

• Design Guidelines

• Zoning Code

• Climate Smart San José

• Transportation Impact Policy

• Parking Management Plan

• Specific / Village Plans

• Greenprint

Public Space Design

Each project is an opportunity to enhance Public Life. It is essential to bring a Public Life lens to city-led projects as well as the design review process for private buildings.

• Parks / Plazas / Paseos

• Complete Street Projects

• Bike / Trail Network

• Transit Network

• Public Amenities

• Interface of private projects with

Programs + Activation

Events, activities and programs attract a range of users into public spaces. Space activation offers an opportunity to leverage the energy of a wide range of community actors.

• City-led Programming

• Co-created Programming

• Resident-initiated Programming

• “Easy Urbanism” Rules

• Creative Placemaking

• Public Arts Programming

the public realm. Programs.

• Transportation Demand Management

Works Cited

Annals of Behavioral Medicine. (2004) “Changes in Neighborhood Walking Related to Changes in Perceptions of Environmental Attributes.” Feb;27(1):60-67

Benfield, K.; Raimi, M.; Chen, D. (1999) “Once There Were Greenfields: How Urban Sprawl is Undermining America’s Environment, Economy, and Social Fabric.”

Center for Disease Control. (2015) “CDC Healthy Places Toolkit 2015.”

Chetty, R.; Hendren, N.; Kline P.; Saez, E. (2014) “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (4): 1553-1623.

City of San José. (2018) “Climate Smart San José: A People Centered Plan for a low carbon city.”

Clifton, K.; et al (2013) “Consumer Behavior and Travel Choices: A Focus on Cyclists and Pedestrians” 92nd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board

Dodman, D. (2009) “Urban Density and Climate Change”

Doherty, P.; Leinberger, C. (2010) “The Next Real Estate Boom” Brookings Institution

Endeavor Insights. (2014) “What do the Best Entrepreneurs want in a City” https:// endeavor.org/insight/endeavor-insightreport-reveals-the-top-qualities-thatentrepreneurs-look-for-in-a-city/

Enos, R.; Celaya, C. (2018) “The Effect of Segregation on Intergroup Relations.” Journal of Experimental Political Science

Enos, R. (2014) “Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes : A test using public transportation in homogeneous communities.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

Gilderbloom J., I.; Riggs, W.; Meares, W. (2013) ”Does walkability matter? An examination of walkability’s impact on housing values, foreclosures and crime.” Cites: The International Journal of Urban Policy and Planning, Volume 42, Part A: 13-24

Hogan, M.; et al. (2016) “Happiness and health across the lifespan in five major cities: The impact of place and government performance” Social Science & Medicine, Volume 162: 168-176.

Holt-Lunstad, J.; et al. (2015) “Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality.” Perspectives on Psychological Science

Humphrey, C.; et al. (2017) “Analysis of Urban Vibrancy and Safety in Philadelphia.” Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania Knight Foundation & Gallup. (2010) “Knight Soul of the Community 2010; Why People Love Where They Live and Why it Matters: A National Perspective.”

Litman, T. (2015) “Evaluation of Public Transportation Health Benefits.” Victoria Transport Policy Institute (VTPI)

Pivo, G.; Fisher, J. (2011) “The Walkability Premium in Commercial Real Estate Investments.” Real Estate Economics, Volume 39 (2):185-219

Rogers, S.; et al. (2013) “Examining Walkability and Social Capital as Indicators of Quality of Life at the Municipal and Neighborhood Scales.” Applied Research Quality Life 6: 201-213

Sallis J.; Troelsen, J.; et al. (2016) “Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study.” Lancet

Stutzer, A.; Frey, B. (2004) “The Stress That Doesn’t Pay: The Commuting Paradox.” Institute for the Study of Labour, University of Zurich

The Guardian “What’s the carbon footprint of ... cycling a mile?”

U.S. Census Bureau. (2016) “American Community Survey 2016 5-year”

Watts, A.; et al. (2015) “Neighborhood Integration and Connectivity Predict Cognitive Performance and Decline”

World Health Organization. (2007) “Global Age-friendly Cities : a Guide” 73.

Wilson, C.; Moulton, B. (2010) “Loneliness among Older Adults: A National Survey of Adults 45+.”

Field Guide #2

Measuring Public Life In San José

Developed by Gehl in partnership with the City of San José and with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

January 2019

How to use the San José Public Life Field Guides

In DEFINING Public Life you will learn the tangible benefits that a diverse, inclusive and vibrant Public Life can offer to our city.

This guide introduces San José’s Vision and Framework for advancing Public Life as a strategic city driver.

MEASURING Public Life provides an overview of the methods used by government agencies and civic organizations around the globe to monitor Public Life targets. This guide also provides recommendations for San José’s data collection initiatives.

NURTURING Public Life illustrates the progress that our city has made in promoting Public Life, and presents practical actions that city agencies and Community Partners can take to further advance the goal of connecting San Joseans to their public spaces.

Key takeaways from Measuring Public Life

1 2 3

Measure what you care about. If the data for what you care about doesn’t exist, find a way to collect it. (p. 8)

Public Life measurements can be used by the City of San José to define success in a variety of areas.

There are tools to measure Public Life at three different scales: the city, neighborhood, and site. Tools and training are available at gehlinstitute.org. (p. 14) 5 4

Leading cities around the world use Public Life metrics in their planning frameworks and day-to-day decisions to ensure that these plans keep people at the center. (p.24)

Tell stories with data. Charts and graphs on their own aren’t enough to catalyze action.

Why do we measure Public Life?

Where are the hotspots? Who is there? What activities are popular? How does the city support or get in the way of how people want to use the public realm?

This Handbook is a roadmap for how the City of San José can measure Public Life to get a baseline of activity, understand latent demands, evaluate the success of a design,

and understand the impact of programming over time. This data can give changemakers the confidence to test ideas in space, monitor their public benefit, and adapt accordingly.

Documenting Public Life can offer valuable insights for design and provide a baseline against which progress can be measured.

Surveyors measure public life activity on Paseo de San Antonio in Downtown San Jose.

Measure what you care about

We measure Public Life to better understand the impact of any project in the public realm. This might include design interventions — like building a new playground — or cultural programming — like a concert series.

People-centered metrics enable you to make an evidence-based case for change, create a buzz for projects, or persuade skeptics to get on board. Such data can also reveal previously invisible or overlooked patterns.

Data collection that focuses only on traffic optimizes for traffic.

WE WOULD LOVE A TABLE HERE

When we measure Public Life, we see what people do in public space — not just what they say.

Observing what people do in public can tell a lot about what's working, and what's missing. While it's important to gather comments directly from residents about what they want from their city, studying public life is actually a kind of ethnography — that is, forming a theory of what's going on through direct observation.

In this way, we can start to understand the "user experience" of the city by seeing where people gravitate to and what they do. While metrics like number of trees planted or miles of sidewalk paved can be useful, "people metrics" (like the number of children playing or couples talking) are experiences anyone can understand and relate to. They bring planning to life.

I WOULD LIKE A SIDEWALK HERE

I NEED A PLACE TO SIT AND WAIT

How can Public Life Data help my Department?

Parks and Recreation

Knowing how many people use different facilities, their demographic characteristics and getting a clearer sense of what people actually do in parks is essential for managing the projects and investing in the types of amenities that community members use the most. Usage data can also clarify misconceptions about how facilities are used.

Planning Department

Getting community members to arrive to a consensus on the priorities can be one of the most challenging tasks of planning projects. Engaging stakeholders in the process of gathering data for a neighborhood-scale Public Life survey can help build a shared understanding of the baseline conditions and strengths present in the community. Public Life monitoring can also provide valuable insights on the progress toward planning visions and goals.

Public Works

As the team responsible for the design and construction of City

parks, public buildings and roads, the Public Works Department can assess the extent to which completed capital improvement projects are meeting their intended goals. Understanding how San José residents use the city’s streets and sidewalks before and after a project can shed light on the features that have the most impact, and where investment has the most impact.

Transportation

Pedestrian and cyclist counts are essential to assess the success of complete street projects and other initiatives to promote multimodal transportation. It's important to understand not just How many people? but also Which people? make up those who walk, cycle and use transit. Observing age and gender of people moving, and understanding what they do in "in between moments" of transit is a more complete way of understanding how San José's mobility infrastructure serves residents. By monitoring change in travel patterns over time, the Transportation Department can track progress towards the goal

of reducing VMT and encouraging the use of non-automobile transportation options.

Environmental Services

More than 1/3 of the CO2 reductions envisioned in the Climate Smart San José are directly related to physical planning factors that also support Public Life – walkability, human scale development, and jobs close to housing. Promoting Public Life creates a reinforcing loop for these goals and invites new partners to reduce San José’s carbon footprint. Public Life data can become another input to San José’s carbon accounting and a check on whether mode share targets are being met, by whom, and where.

Additionally, environmental services projects that intersect with the public realm, such as stormwater facilities, can be opportunities to partner with other agencies and leverage additional funding, stakeholders, and benefits. Public Life data helps target sites for environmental infrastructure where social co-benefits are also needed.

Economic Development

Communities’ social offerings, openness, and aesthetics are, in that order, what influence residents’ attachment to their communities.* That attachment translates into attraction and retention of talent in the workforce, as well as reasons people visit San José and choose to start businesses here.

Public Life data can provide a proxy measure for areas of San José where public realm vibrancy translates into retail sales (footfall) and 18-hour neighborhoods that support a mix of urban activities that attract large employers.

Housing Department

Public Life data can provide valuable input into the design and programming of housing projects to enable them to contribute to neighborhood vitality and activate the street. Opportunities exist for the Housing Department to encourage and support active ground-floor development that can be informed by Public Life and respond to neighborhood needs — providing housing but also building healthy neighborhoods.

The Housing Department can prioritize Public Life as the outcome of projects funded by its federal block grants, and continue to use Public Life data to measure project impact. Arts and community organizations could even partner with the Housing Department to activate neighborhood-serving groundfloor uses.

Office of Cultural Affairs

OCA already has great Public Life data in the form of the many event permits it administers. These can provide insights into who, where, and what is enlivening the public realm. But even more fine-grained Public Life data about who shows up for events can provide powerful evidence for what’s working, encouraging private investors and partners. Data that shows the add-on benefits to local businesses — from things like increased footfall or bike ridership — can make a broader case for Public Life investments. Tying these data points to other quality of life indicators, like property crime and pride in a neighborhood, can help to tell a broader story about why investment in one event or neighborhood is part of an effort that helps the whole city.

“I would like to have a profile with data from every neighborhood, not just demographics, but also health, wellness and Public Life.”

— Housing Department

What does people-first data look like?

A guide for documenting human behavior in public.

Getting out to see who uses a space delivers new insights for how to foster Public Life.

People-First Metrics at Three Scales

Methods for measuring Public Life telescope from the small, fine-grain scale of individual parks and plazas, to the large, citywide scale where the socioeconomic trends and street networks are analyzed.

It’s important to measure life and space together. The tools outlined here suggest how methods can be paired based on the spatial resolution of a study area and the survey manager’s research questions.

1 2 3

Site Scale

People data at the site scale can address. like: Who is visiting this plaza? Who's not here, even though they live nearby? What design features invite young or older people? If we put in a bench near the entrance, would anyone use it to wait for friends to meet them?

Neighborhood Scale

Neighborhood-scale Public Life data can draw on a variety of observational and "big data" sources to answer questions like: How do residents get around the neighborhood? What are the major destinations and attractions? Which streets are thriving and which ones need help?

Citywide Scale

Citywide Public Life data reveals the pulse of San José's different districts, how people move between their homes and jobs, and where people spend time for different types of outings. It can also show how large, important features, like the Guadalupe River Trail, perform across different neighborhoods and where connectivity and investment is needed.

Getting a Pulse of the City

Much of the data that is currently collected by the City can shed light on the current state of Public Life in San José.

A combination of desktop research, looking at existing data, and targeted resident outreach can provide an overview of Public Life in the city today.

Some guiding questions might include:

• What places do people love in San José today?

• What qualities draw them to these spaces?

• Where do people wish they could spend time but don’t — and why?

• What are some qualities that people aspire to in their public realm?

• What is the event calendar of the city?

• Is there an emerging cluster of certain business types?

• Are new hotels coming online?

• Is there an emerging tourist hub?

Engaging People

Where they Are.

Pop-up workshops asking regular San Joseans questions can help identify initial opportunities and challenges, and even begin to clarify some shared community values.

A profile of San José’s Public Life can be drawn by analyzing information that is currently available across a range of departments

% %

Outdoor public events

Number of publicly accessible outdoor events in key public parks and plazas.

Permits for street closure

Number of permits issued by the city to close streets for cultural/ public events.

% % $

Mode share

Number of travelers using a particular type of transportation or number of trips using different types of modes.

Presence of cultural institutions

Amount of events hosted by cultural institutions in public spaces throughout the city.

Sales tax from local / independent businesses. Tax revenue percentage from local & independent businesses and where they are concentrated.

Presence of civic organizations

Number of events that civic organizations were involved in or hosts in public spaces throughout the city.

Resident satisfaction

Polls that measure residents’ satisfaction rate for their neighborhoods and public spaces.

% $ $$

Price diversity

City areas that have a variety of price points, help identify places that invite diverse people.

# #

# #

Social media

San José’s Public Life in social media postsis an indicator of how many people are using public space and how they feel about it.

Organizing a Public Life Survey

Observing and measuring the rhythm of everyday life in the city helps sharpen your study questions, can confirm or myth-bust initial hunches, and points to new opportunities and challenges.

The essence of a Public Life Survey measures how people move through the city on foot and bicycle, where they stay, for how long, and what they are doing. Here are the steps to follow when organizing a Public Life Survey — whether for a small section of city blocks, or a citywide district.

DETERMINE YOUR RESEARCH QUESTION

Surveys work best when they are built around a central research question. Your research question can be fairly broad, but it should address something measurable, and it should be directly related to your project goals.

For example: What parts of the Guadalupe River Trail serve families with children? What amenities create places where those groups stay longest?

DETERMINE THE SCALE OF THE SURVEY

When deciding on the scale of the survey, think about how much of the wider context you need to capture to understand use patterns on a particular site.

For example: We need to include neighborhoods within a 15-minute walk of the Guadalupe River to capture the Trail as a neighborhood amenity. We'll measure how much each crossstreet contributes visitors, as well as census information for each neighborhood the Trail passes through.

Digital tools and counters can be terrific time savers and their accuracy is improving with each iteration. Quantitative information about pedestrian or cyclist volumes is a great complement to the more nuanced and context-rich information that can be obtained through an observational study.

PICK THE RIGHT TOOLS EXECUTE THE SURVEY PLAN THE SURVEY

The Public Life tools are used to collect data about people that will provide insight into the impact of your projects, inform stories about this impact, and leverage those stories to create change.

The fewer people in a space, the more detail you can observe. The busier the place, the less detail you can observe.

For example:

Once people get to the Trail, what features invite them to stay in one spot? We need to measure stationary activities and inventory amenities around each place we see people lingering.

Estimate what to survey (and where to do it) based on your research questions, framework, and selected tools.

For baseline data collection, Start with your most typical weekday and weekend (usually a Wednesday or Thursday and Saturday). But there's usually a market on Wednesdays! Measure those days too.

Identify a survey manager who will execute the survey (maybe it’s you!). This person will oversee the survey, check in with surveyors and be available for questions. Remember to document the process: take photos to register the survey in action and the places being surveyed.

Public Life Tools

Pick the right tools to measure Public Life. Stay focused on your research question and start with simple tools you can execute. Even a little Public Life data goes a long way.

The cards on the right describe the six core Public Life tools.

To download the full toolkit including printable data collection forms, and to watch fun instructional videos, visit: www.gehlinstitute.org.

Pedestrian and Cyclist Moving Counts

A key baseline of a city’s Public Life is the nuance of how people move through space.

WEEKEND PEDESTRIAN MOVEMENT

How many people are moving through the space? Where? When?

This tool provides data on how people move around the city. The counts give an indication of activity levels and destinations that attract people.

Downtown is full of adults some exceptions. Where are young people choosing to go instead? we learn from places and times have multi-generational public

Stationary Activity Mapping

This ethnographic method records how people ‘vote with their feet’ and uncovers use patterns among different demographics.

How many people are there? What are they doing? Where? When?

This tool provides a snapshot of what people choose to do in a public space. It indicates what activities people do in the public realm throughout the day such as standing, sitting, playing, engaging in sports and cultural or commercial activities. Diversity in types of activities and number of people spending time indicates how well a public space is performing, and how successful it is in inviting people to

lunch activity

Average 461 people/hr dinner peak

Intercept Survey and Questionnaires

There are some things you can only learn about a space by asking someone directly.

Building Facade Activation and Entries

Good spaces have good edges. The activation of a facade and the number of entrances is a strong predictor of when people will slow down and engage in activities other than simply walking.

Interactions among strangers

Race & Income

Who is interacting and how?

Inviting public life is only the first step to a better Market Street. A truly great street also encourages conviviality among those who enjoy it. MSPF was generally successful at creating a social environment, but interaction was more commonplace for some groups than others. Over 70% of survey respondents identifying as White or Black reported having interacted with a stranger on Market Street during the Festival, compared to only half of Asian respondents and 21% of Hispanic respondents. It is difficult to discern whether this discrepancy is due to linguistic barriers, cultural barriers, or a lack of outreach to Asian and Hispanic communities. Our study found no discernible relationship between social interaction and income, suggesting that differences in income were not a barrier to creating a convivial environment across economic classes.

What does this interaction lead to? Do people of different socioeconomic backgrounds spend time in the space?

The intercept survey allows us to compare the “invisible” qualities of Public Life to things we can observe and measure.

Did you interact with someone new on Market Street today?

Although a broad mix of people attended the Festival, not all of them were aware of it prior to encountering it. Those who identified as White were four times more likely to come to Market Street for the Festival than those who identified as Black, who were more likely to partake in the Festival because they were walking by.

Improvements to inclusivity for the Festival can be made among the group of prototype designers themselves, of whom approximately 73% identified as White and only 7% and 3% identified as Hispanic or Black, respectively.

How permeable, transparent and inviting are ground floor building edges? How granular is a facade?

Did you interact with someone new on Market Street today?

People who identified as Asian and Hispanic were much less likely to interact with strangers during the Festival, but the reasons for this difference are not clear.*

What brings you to Market Street today?

People who identified as White were more likely than people who identified as Asian, Hispanic, or Black to visit Market Street specifically for the Festival, suggesting room for improvement in invitations to minority communities.*

12 Urban Quality Criteria

The 12 Quality Criteria help us understand and compare quality in the built environment and its ability to either contribute to the flourishing of Public Life diversity or hinder it.

Protection against traffic & accidents

Protection against crime & violence

Protection against unpleasant sensory experiences

This survey complements quantitative data and can be correlated with the amount of Public Life diversity in a space.

An inviting place that encourages Public Life has elements of protection, comfort, and enjoyment.

Opportunities to walk/cycle

Opportunities to stop & stay

Opportunities to sit

Opportunities to see

Opportunities to talk & listen

Opportunities for play & exercise

Dimensioned at human scale

Opportunities to enjoy microclimate

Aesthetic qualities

Setting PeopleFirst Targets

Some cities are leading the way by setting targets, evaluating impact, measuring success and following up — to make their cities more livable.

COPENHAGEN

Metropolis for People and Co-create Copenhagen set clear and ambitious people-first targets.

NEW YORK

One New York, follows PLANYC, as the city’s guide to track inequality at the regional scale.

SYDNEY

The city of Sydney’s Sustainable Sydney 2030 sets three overarching visions to be Green, Global, and Connected. Ten specific, measurable targets were set to achieve those goals.

SAN FRANCISCO

The Civic Center Public Life Framework used a baseline Public Life study to set a series of metrics to assess design proposals and interim activation.

MEXICO CITY

Mexico City’s Plan CDMX seeks to define a compact city structure by creating more integrated neighborhoods — spatially, socially and economically from structured public transport systems to proximity to services.

MELBOURNE

Melbourne has a responsive online database Pedestrian Counting System, and Places for People guiding plans, which establish a platform of evidence to guide city planning.

MINNEAPOLIS

Minneapolis’s Parks and Recreation Board uses just seven easily-measurable metrics to align their capital spending with their commitment to racial equity.

LONDON

The London Plan delivers an integrated social, environmental, economic and transportation framework for the city’s development over the next 20-25 years.

“Once you can show people that you are going in a positive direction, it’s much easier to keep going.”

— Rob Adams

Director of City Design at the City of Melbourne on the importance of measuring Public Life.

SETTING PEOPLE FIRST TARGETS

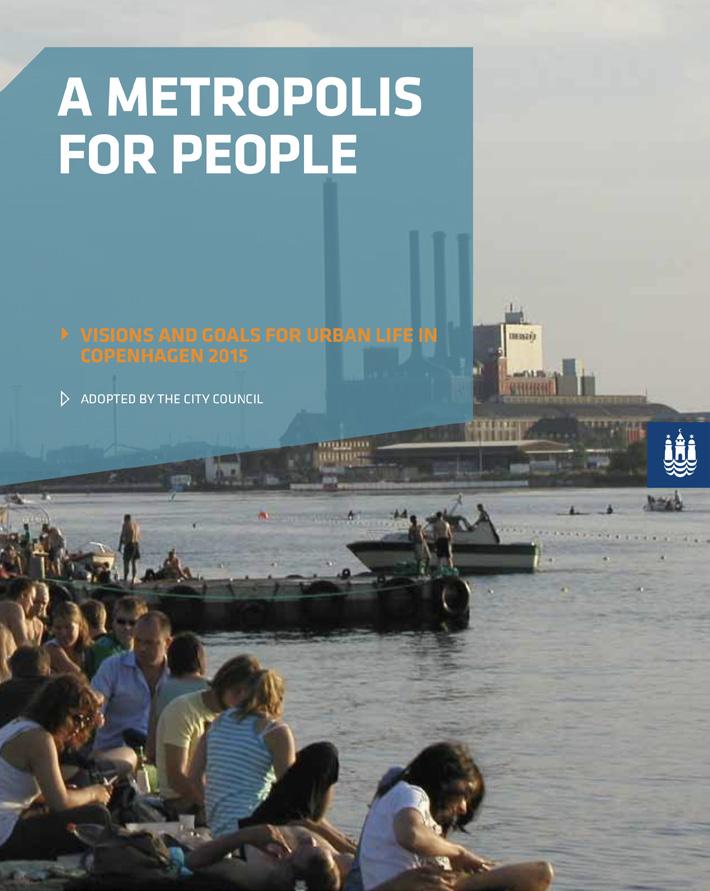

Copenhagen

Beginning in 1965, Public Life data, primarily collected by Jan Gehl and colleagues, has shaped city targets around people.

A Metropolis for People

"More Urban Life For All"

By 2015, 80% of Copenhageners will be satisfied with the opportunities they have for taking part in urban life.

More People Walk More: To increase the amount of pedestrian traffic by 20% by 2015 compared to today.

More People Stay Longer: By 2015, Copenhageners will spend 20% more time in urban space than they do today.

For more, visit: www.copenhagen.com / akasal

"A Lively City"

90% of Copenhageners consider their neighborhood lively and varied. 70% consider the city a green city.

"A City With An Edge"

A majority of Copenhageners consider Copenhagen a city with an edge, a city that reflects the diversity of its population and allows for individual differences.

A Responsible City: 75% consider Copenhagen a green city.

For more, visit: www.copenhagen.com / akasal

Melbourne SETTING PEOPLE FIRST TARGETS

Beginning in 1993-4 with the city’s first Public Space Public Life Survey, the City of Melbourne has been measuring pedestrian activity. Today, a 24-hour pedestrian counting system measures pedestrian activity in the city each day and makes the data available on a dynamic public website.

Melbourne's most recent long-term study "Places for People" (2015), documents how the urban environment is changing. It focuses on how people use the City in their daily lives – from buildings, to streets, open spaces and gardens. The study provides the latest baseline data with the aim of improving the quality of life in the City, by informing thinking, planning and design.

1982

Like many business districts without housing, the center of Melbourne used to get empty at night. The alleys (or "laneways") were mainly used for service and trash collection.

1994

A new set of policies to be transformed make the center

policies that permitted the laneways transformed into places for people helped attractive to new residents.

Places for People

Since 1993, Places for People has collected information for each decade to produce longitudinal data to monitor use and qualities of Melbourne's urban space. It brings together a substantial set of data on the city’s condition – looking at Urban form, People, Public Space, Built Form and Land Uses – and offers important new insights into both the city and city life that will be vital for planning Melbourne's growth and development.

Pedestrian Counting System

In Melbourne an online platform has been keeping a pulse on Public Life since 2010. In 2013 the system was updated to show hourly and realtime counts of pedestrian information.

For more, visit: bit.ly/2CZkshi

For more, visit: pedestrmian.melbourne.vic.gov.au

New York SETTING PEOPLE FIRST TARGETS

In 2007 Mayor Bloomberg promised that New York would become the greenest, greatest city in the world. To do this, the Department of Transportation needed to re-imagine New York as a sustainable city on a human scale.

2006

A Public Life Study revealed that cars occupied close to 90% of Times Square, even though 90% of visitors were on foot.

2008

This data helped generate the political momentum to transform Times Square into a place for people. Literally overnight Times Square was closed to traffic and temporary furniture was moved in.

“In God we trust. Everyone else bring data.”

— Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg

2017

The positive response from New Yorkers was instant. Times Square was the first of the key pilot locations to be completely and permanently transformed

PlaNYC, A Greener and Greater New York, released in 2007 outlines measures to address the city’s aging infrastructure, support parks, improve the quality of life and health for New Yorkers and commit to a goal for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Updated in 2011 to include strategies to improve livability, some of PLANYC’s key metrics include:

• Everyone lives within a 10 minute walk of open space

• Expanded options for sustainable transit

• Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by over 30%

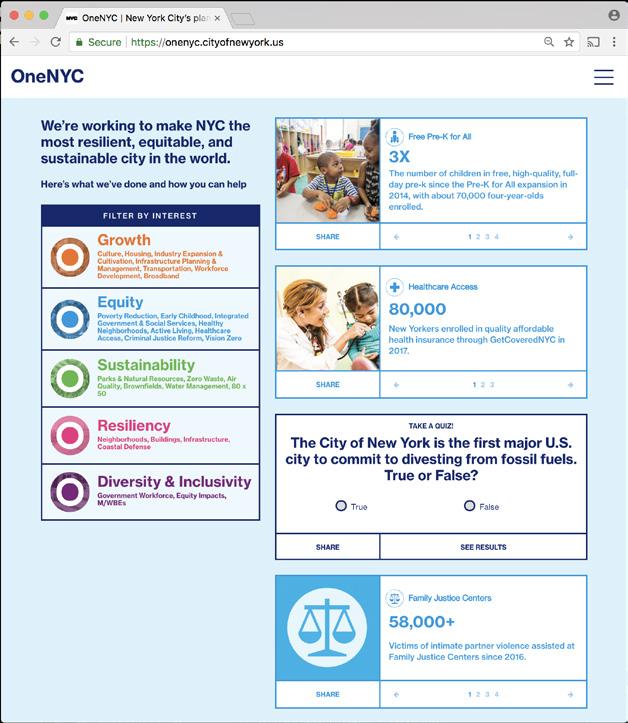

One NYC

ONE NYC, a vision first released in 2015, continues to drive at PLANYC’s overarching goals of growth, sustainability and resiliency, but with a more regional perspective and a focus on inequality. In addition to this, the report now lives on a dynamic online platform, where updates and key information can be shared regularly. Some key metrics include:

• 80,000 new affordable housing units

• 20% increase of overall rail transit capacity into the Manhattan core

• Zero traffic fatalities

• 80% of adult New Yorkers meet physical activity recommendations

For more, visit: https://tinyurl.com/y7vylkep

For more, visit: https://onenyc.cityofnewyork.us/

Field Guide #3

Nurturing Public Life in San José

Developed by Gehl in partnership with the City of San José and with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

January 2019

How to use the San José Public Life Field Guides

In DEFINING Public Life you will learn the tangible benefits that a diverse, inclusive and vibrant Public Life can offer to our city.

This guide introduces San José’s Vision and Framework for advancing Public Life as a strategic city driver.

MEASURING Public Life provides an overview of the methods used by government agencies and civic organizations around the globe to monitor Public Life targets. This guide also provides recommendations for San José’s data collection initiatives.

NURTURING Public Life illustrates the progress that our city has made in promoting Public Life, and presents practical actions that city agencies and Community Partners can take to further advance the goal of connecting San Joseans to their public spaces.

Key takeaways from Nurturing Public Life

1 2 3

San José’s Guiding Framework for Nurturing Public Life advances Public Life within three main focus areas in the city’s planning and design process: Urban Planning, Public Space Design, and Programs and Activation. (p. 6)

Focus Area 1: Urban Planning can be used to foster Public Life by creating a platform that encourages: density and a mix of uses, more opportunities for San Joseans to be outside and active in their communities, and sustainable modes of transit. (p.8)

Focus Area 2: Design of Public Space should first consider the life inherent within the place, then the role of public spaces and, finally, the buildings that define the edges. (p.12) 4 5

Focus Area 3: Programs and Activation can go a long way in setting the conditions for Public Life to flourish. Alongside Community Partners we can create lively, inclusive and attractive places that invite San Joseans to stop and stay. (p.18)

Bring Public Life to the table with five checklists that ensure Public Life makes it into every meeting with colleagues, counterparts in other departments, developers and Community Partners. (p. 24)

San josé’s guiding Framework FOR NURTURing Public Life

To advance Public Life, city agencies can collaborate on three focus areas: Urban Planning, Public Space Design and Programs and Activation.

URBAN PLANNING

PROGRAMS AND ACTIVATION

Focus Area 1: URBAN PLANNING

San José has already adopted plans and policies that promote urban vibrancy.

Long-term strategic planning is one of the areas where San José has a leg ahead. The city has succeeded in adopting a land use and transportation agenda that seeks to add compact Urban Villages instead of growing out, to target growth in transit-oriented settings and to improve the physical form of the city. creating a “city of great places.”

The policies are in place, this vision needs to be upheld and implemented!

San José's General Plan, Climate Smart, Bike Plan and other strategic efforts are aligned in aiming to improve the job-housing balance, putting the city on a sound fiscal footing and shifting transportation patterns away from dependence on private cars. All of these policies will also improve Public Life.

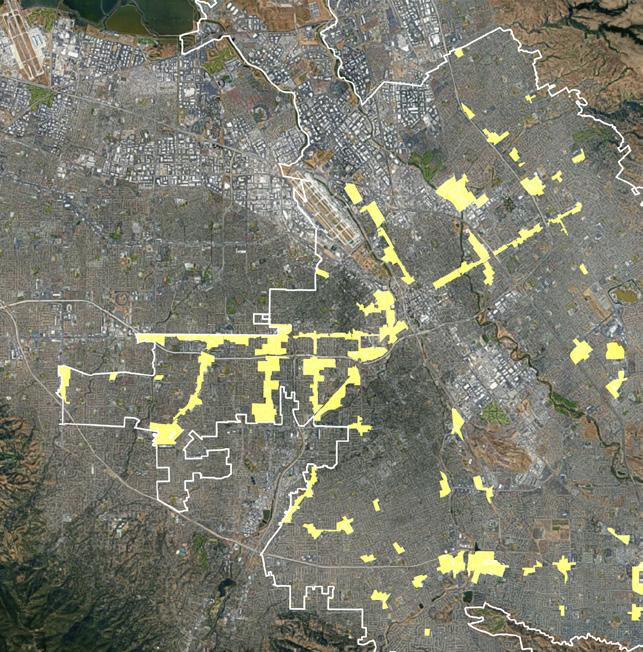

One of the most important land use strategies that the city is pursuing is to promote the development of 70 Urban Villages in San José. Urban villages are pedestrian-, bike-, and transit-friendly neighborhoods with a mix of homes, shops and jobs. They will enable San José to accommodate its share of the region’s growth by building up in targeted areas instead of sprawling out.

San José’s Urban Village Plan: The General Plan designates nearly 70 Urban Villages along some of the city’s main corridors. The urban villages will help provide amenities and services that are lacking in residential suburbs, while permitting the development densities needed to support higher standards of public transportation.

This plan helps inform and set goals on how City staff and policy makers use the Greenprint as a guide to explore the ways the parks system can help people in San José be healthier and improve their quality of life. The City is working on a major update of its existing Greenprint, and is extensively engaging with the communities that will benefit from these capital projects.

“Urban Villages are what we are all about. Public spaces make this city shine. This comes up in community meetings. Residents want places where they can be social. Streets build our sense of community.”

—Michael Brilliot Deputy Director, Department of City Planning

Urban Villages provide the densities and mix of uses needed for Public Life to flourish

The Greenprint sets goals and strategies for how San José’s parks, trails and community centers will grow and improve Public Life

Climate Smart San José delivers a view of sustainability that balances an aspirational lifestyle with environmental stewardship. Through the engagement process, San Joseans expressed a desire to achieve a lifestyle that allows more opportunities to spend time with friends and family, be active, live in a safe neighborhood, have freedom to explore, share great experiences and have access to parks and nature.

This expanded definition of a Good Life requires building a city where people spend less time in traffic and more time having experiences and opportunities to be outside and active in the community.

Advancing the Climate Smart Strategies will help make the city more vibrant and lively.

CLIMATE SMART STRATEGIES

• Transition to a renewable energy future

• Embrace our Californian climate

• Densify our city to accommodate our future neighbors

• Make homes efficient and affordable for families

• Create clean, personalized mobility choices

• Develop integrated, accessible public transport infrastructure

• Create jobs in our city to reduce vehicle miles traveled

• Improve our commercial building stock

• Make commercial goods movement clean and efficient

The Good Life 2.0 is about having more time for family and communityconnecting in Public Places

1D Streets for walking, biking and transit

A city’s vitality is deeply intertwined with the mobility choices of its residents. Public Life can’t thrive unless people feel as safe and comfortable walking, biking and sharing a transit experience as they would taking a car. People’s decisions about mode share, in turn, are influenced by the design of the environment. San José’s Complete Streets Design Standards & Guidelines summarize current best practices to ensure that the streets of San José balance the safety and comfort of pedestrians, cyclists and transit users, with those of drivers. The principles upheld in this document support Public Life, neighborhood livability and economic vitality and set the policy framework for individual retrofit and street design projects.

Our city is in the process of rolling out one of the nation’s most ambitious protected bikeway projects, which is helping make it safe and convenient to ride a bike or a scooter. These improvements are helping drive a change from auto-dependency to an expanded range of mobility options.

Large blocks with dead ends, wide roads, and few choices.

A walkable grid provides a legible network, route choices and caters to the human scale.

“Densifying our city in focused growth areas increases walkability and cycling, and makes our neighborhoods more vibrant, distinctive and enjoyable.”

Climate Smart San José

Focus Area 2: design of the public realm

First consider Life, then Space, then Buildings Life

Vibrant neighborhoods are mixed use and accommodate a wide range of activities, functions, spaces, people, building typologies, dimensions, tenure, and affordability.

Space

Public spaces are the driver of social interactions, local economy, connectivity, mobility, creation of culture and memory of a place.

Buildings

It’s important to care about the smaller scale — the detailing of buildings, active ground floors, edge zones, number of doors to a street — as well as the overall massing and density of developments.

Diversity at the ground level

Vertical diversity: Mix of functions and uses from floor to floor

Stacking and mixing functions allows vertical flexibility in a building’s uses. This allows the building program to adapt to evolving economy, culture and market demands over time.

Horizontal diversity: Small units, many entrances

Integrating residential, work, retail, and entertainment into a block creates dynamic places people want to spend time. The mix of functions within a block is essential to achieve more compact and walkable neighborhoods.

Inside–Outside Connections:

Permeable frontages

Small scale frontages with high levels of permeability ensure ‘eyes on the street’ at all times of the day. Entrances and openings invite people to enter, generating activity and movement at ground level.

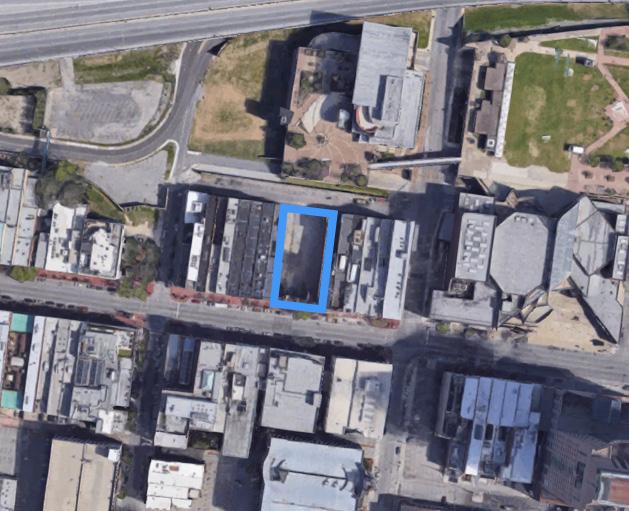

San José is updating design guidelines for Downtown/ Diridon Station Area to support placemaking goals for this area.

2B Transition Space

Soft edges transitioning from public to private.

For residential buildings, a gradual transition between the public realm and private residential spaces is desirable. It is important to ensure that this treatment of the ground floor is present on individual projects.

Stoops, front porches/patios and overhang balconies are good examples of soft edge elements that create a gradual transition from public to private spaces. These elements also foster human scale cues that contribute to a more walkable environment and a better sense of safety and comfort.

San José has design guidelines in place, the challenge is enforcing them through the building review process.

Introverted vs Extroverted Urbanism

The project review process should be strengthened to ensure that the ground floor of each residential or commercial project contributes to the visual quality of the public realm and connects the project to other destinations primarily through walking. We need to move away from trying to activate dead spaces with events towards designing spaces that aren’t dead to begin with.

Introverted urbanism tends to separate private and public space, it looks inwards and isolates people from its surrounding context. It has failed in fostering human scaled edges and spaces that contribute to Public Life. This type of urbanism varies in scale: from stand alone single family homes in the suburbs to high density residential/office towers in cities.

Extroverted urbanism, on the other hand, invites life – by creating soft edges on buildings, enhancing the quality of the public realm, and generating programmatic activities that foster people to stay and interact with others. These qualities contribute to a city's sense of safety, comfort and delight.

For San José the challenge is not to create more public spaces, but to attract life and activities to the places that already exist.

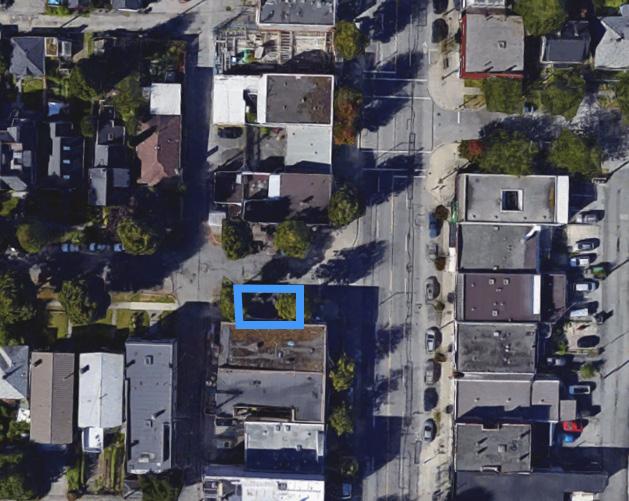

Parklets

>1000 Sqf

Smaller-scaled spaces, programmed and designed with higher quality elements, create a stronger sense of ownership, stewardship, and Public Life. Large-scaled spaces need high density immediately nearby to create a "walk-shed" of many users which keep them constantly filled. Large spaces also need a high level of stewardship, management and programming.

SIZE

Life can flourish in small spaces. Spaces of half acre or more require substantial density and programs to attract a critical mass of visitors.

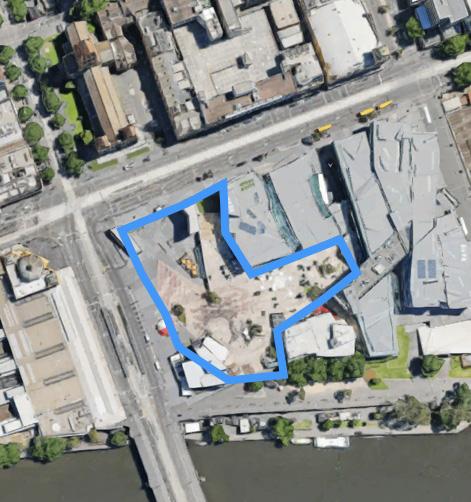

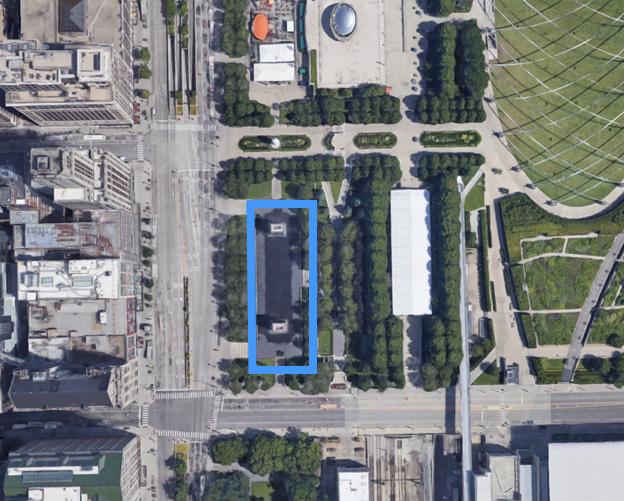

For public spaces, quality is more important than quantityFederation Sq., Melbourne 2 Acres Crown Fountain, Chicago 1/2 Acres Resurfaced Plaza 1/4 Acres

The effort of re-imagining the Guadalupe River is an opportunity to enliven it and make it a place where people want to be. What scales of spaces would it need and at what density?

2E Scale and enclosure: Two dimensions of public spaces

Public spaces can be classified in terms of their capacity (how many people can use the space?) and control (how enclosed and how public or private does this space feel?). Consider this framework when reviewing public spaces to understand if the design is well-matched to the surrounding uses. Not all public spaces serve the same function!

Melbourne Union Sq., New York City

5 Acres

Capacity

Low Control

High Capacity

Clearly public (Public Square, Park, Street)

High Control

High Capacity

Sense of Safety and Ownership

(Semi private enclosed courtyard)

Low Control

Low Capacity

Unclear ownership (Semi Public Open Courtyard)

Control

Source: Urban Form and Social Territory

Eva Minoura, KTH Royal Institute of Technology / School Of Architecture And Built Environment

High Control

Low Capacity

Clear Ownership (Private Garden)

Focus Area 3: Programs & Activation

Getting the right mix of people, programs and activities sets conditions for urban life to flourish

San José nurtures a culture of vibrant Public Life through pilot projects, park activations, complete streets events, and art installations – possible through close collaboration with our Community Partners. These types of activities help to create lively and attractive destinations that (1) generate more invitations for lingering and walking, (2) invite diverse audiences in terms of age, gender, neighborhood, income and racial identification, (3) present opportunities for greater social interaction, (4) bring new resources and services to the street that expand cultural and economic opportunity and (5) engage the community in the planning and design process so they can take an active role in shaping their neighborhood public spaces.

VivaCalleSJ is an open streets program that turns miles of streets into places for people in San José. VinaCalleSJ has proven to be a great success, not just in attracting participants, but in recasting "what the street is for" in the minds of San Joseans. There is an extraordinary opportunity and potential to build on its momentum and strength, by amplifying this program and ensuring its continuity.

Night Market in Japantown is a great example of how the city can make adjustments and become more nimble in facilitating neighborhood Public Life.

MUSICAL SWINGS

RE-IMAGINING THE GUADALUPE RIVER

Neighbor Nights is a free event that takes place every second Friday of the month at community centers throughout San José. The event provides community members with the opportunity to take part in an array of activities including music, movies, dances, crafts and sports.

JAPANTOWN

FOUNTAIN ALLEY POP-UP GALLERY

JAPANTOWN

FOUNTAIN ALLEY POP-UP GALLERY

Remove Barriers to Participation

Remove hurdles to resident-driven activities in order to encourage participation and shape spaces that are created collectively for, and by, the community. Streamlined application processes with short turnaround times, funding for neighborhood groups and event resources that are easily accessible to the public, free or low-cost block party and event permit fees and even streetlevel power outlets are all means to encourage more San Joseans to become active participants.

There are reasons to visit... Create reasons to stay.

Creating invitations to visit and stay is key to spurring strong everyday Public Life. Events and programs should be strategically scheduled to boost a dip in daily or weekly activity.

San José programs like ‘City Dance’ help to fill in the gaps through the day and week to create everyday Public Life.

Retirees happy hour “Learn about San José”

“The primary purpose of the recreation department is to get people together. We started

the

of the community.”

— Neil Rufino Deputy Director Recreation and Community Services Division

Build on interim projects for longterm gain

What does a street party have to do with investments in multi-modal infrastructure?

VivaCalleSJ — San José’s biggest street party — has encouraged tens of thousands of residents to experience the streets as places to walk and bike. As the city rolls out miles of new protected bike lanes, the experience of the city by bike is part of more people’s lives than ever before. Drawing the connection between temporary experiences and permanent investments can be a way to build enthusiasm for change. The more residents

have personally experienced the benefits of proposed changes, the more they are willing to support them politically. Temporary and pilot projects help build local champions.

Stories based on data and evidence — like “75% of Viva Calle participants spent at least $11 more than they would have otherwise” — become a powerful step in building the case for more permanent investments.

Think of pilot projects as a communications project with a physical component. Drawing the connection between the temporary and the permanent is more than a policy exercise, it requires skilled public relations and making the connection explicit.

Strategic Vision Urban Transformation

Learning From Denver 16th St Mall

BEFORE

ACTIVATION

1% of people walking through chose to stay.

AFTER

ACTIVATION

88% increase in staying activity

In Denver, 16th Street is the city’s most important transit route with over 45,000 commuters a day moving through and over 28,000 people walking the outdoor mall. Viewed through this measure, 16th street is a success.

But walkability isn’t enough. Only 1% of people who walk the mall stop to stay and spend time there, retail is suffering, there is antisocial behavior and the street’s infrastructure repairs are over $5M per year.

In 2015 a temporary activation event kicked off, ‘Meet in the Street’, to address some of these challenges. The street was closed, the buses were re-routed, and temporary elements were installed throughout. The Transit Department was invited to experience the street, and the success of the event was evident - there was an almost 90% increase in the number of people stopping to stay, demonstrating that the space was creating more invitations for lingering and potential for social interaction.

From Regulator to Facilitator

Action-orientated planning, which is neither top-down nor bottom-up, is a planning approach that relies on both the city and its citizens. By focusing on action-orientated planning, the City of San José can take on the role of facilitator, while citizens can drive the actual change and inform major decisions. As interim pilot projects move towards long term solutions, the direction is steered from both the top and bottom, ensuring a more holistic and resilient final outcome. This relationship helps the citizens build and influence the building of their own city - creating a city for San Joseans, by San Joseans.

The generation of a pilot project by community or residents groups can help ensure a strong sense

of ownership. This model of city-facilitated, user-generated projects requires an engaged community that can help with both implementation and maintenance. If these types of projects are to some degree facilitated by the city, the long-term impacts can become more transparent as the project is guided towards alignment with other ongoing initiatives.

No matter the type of project, a pilot can serve as a platform for citizen engagement and a more democratic approach to public space design. San José can empower proactive citizens and local champions to be co-creators of the public realm and engage diverse communities in order to reach better, more inclusive and sustainable outcomes for the public realm.

MAKING Public Life EASY EVERYDAY

Five checklists to ensure Public Life doesn’t fall through the cracks.

The following checklists provide simple questions to ask in meetings with colleagues, counterparts in other departments and agencies, developers and Community Partners.

San José's guiding Framework FOR NURTURing Public Life

Revisit these questions early and often — when specific opportunities to foster Public Life are addressed, the easier it is to scope, review and regulate the projects that make a people-first city.

What does having Public Life on the agenda look like?

Discussing creating a Benefits District to provide cleaning and maintenance of public amenities.

Ensuring block party permits are easy to get, and advertising how to do it online.

Writing an RFP that asks for an approach to making youth and seniors feel welcome in the plaza.

Lifting minimum car parking requirements and providing adequate bike parking where it's needed.

Foster a Culture That Values Public Life

What makes it onto the meeting agenda is driven by the culture of your workplace. What’s on the agenda — and what’s not — reinforces shared values within teams and across departments.

If you are setting the agenda, make time to talk about Public Life goals and outcomes early and often in projects.

If you need help getting Public Life into the discussion, refer to Handbook 1 for adopted San José policies that are supported by Public Life. Referring to policy helps illustrate what’s at stake and how to create multiple benefits.

Have Public Life outcomes been included in the project definition and scope of work?

Have we discussed the City policies and planning goals that can be supported by Public Life in this project?

Does this project or service build on Public Life that’s already present?

Do our success criteria include people-focused metrics?

What budget is available for maintenance, stewardship and continued refinement?

Are we anticipating unintended consequences that a project or initiative may have on Public Life?

Are we communicating our successes in terms of: benefits to daily life, community cohesion and ability to spend more time in public?

Leverage Community Organizations and the Public

There’s no Public Life without a public. Government can regulate, but it can also enable, creating a platform for participation, stewardship and ownership.

Every project and policy that affects the public realm should consider how stakeholders, community organizations, and the general public can be co-creators with the City.

Has the community asked for what we’re proposing? Have we done an assessment to find out what is most needed?

Who are the champions of ideas that align with the City’s strategic priorities? Can they be given a role in the process?

Who, from those who will be affected, hasn’t been heard from? How could we lower the barriers to engagement to make it more likely they can make their voices heard?

Have community members been invited to scope and co-create this project or program (rather than just sign off)?

To ask when designing community meetings and workshops:

Have we provided a way for the public to propose positive vision(s) of their own?

Have we asked community members with relevant expertise and resources to show up?

Are we explaining how this project will improve quality of life for the people who show up?

Measure What You Care About

As the capital of Silicon Valley, San José is uniquely positioned to leverage data and evidence-based stories about how the city serves residents. Yet like most cities, San José collects more data about vehicle traffic than about how people live their lives in public.

Viva CalleSJ successfully brought 130,000 San Joseans into the streets in 2017, reducing crime by 44%, lowering CO2 emissions and contributing to a measurable rise in local retail spending during the event. By tracking this data, event organizers have been able to make the case for budgeting to expand this highly popular event. But without more data on age, gender and socioeconomic factors of the people using (or not using) San José’s public spaces, it’s difficult to make changes. There should be just as much “people data” available as “car data”.

Have we identified measurable Public Life goals for this project?

Are all San Joseans visible in our measurements (age, gender, income, etc.)?

Do we have a plan for collecting, analyzing and reporting Public Life data in this project?

Are we sharing the story of our work using people-centered metrics?

Have we tied our people-focused metrics to the goals of San José’s guiding plans: Envision San José 2040 (example: TR-1.3, increase walking and biking to 15% mode share)

Is there a way for us to follow up on a built project in 1-2 years to see if it’s delivered on Public Life expectations?

How might we be able to change course if people-focused data told us something different than we expected?

Is there a mechanism for using peoplefocused data to inform design?

Create Great Public Destinations Connected by an “8 to 80” Network

Great destinations — parks, plazas, shopping districts, foodie hotspots, natural areas — have a multiplying effect when they’re linked by streets and paths comfortable and safe enough to leave the car at home. This allows residents to stay out longer, spend more time in public, and include more diverse people in their group.

People tend to chain several destinations into a trip, especially on weekends. Think about leaving work, going to the gym, and picking up groceries on the way home. Or taking the kids and grandparents to watch a soccer game, then getting ice cream near the park on a Saturday.

Destination amenities should always be considered within a network of active mobility designed for the capabilities of the youngest, oldest, slowest, and least-experienced users. The reason that a family will leave the bikes at home isn’t usually mom and dad — it’s that the street doesn’t feel safe enough for the kids. Once amenities become networked, the effect for San José will be exponential: the journey becomes a new destination.

Does this place invite a diverse public and provide reasons to stay?

How connected is this place to its immediate surroundings?

How enjoyable and safe is it to walk, ride or take transit from the nearest 'other destinations' to this place? Would a child be able to make the trip easily with their grandparent? Is the journey clear and legible?

Can this project strengthen and enhance the City’s primary active mobility and transit routes?

Between here and the next closest attraction, are there basic amenities like water fountains, places to sit, shade, wastebaskets, every 1/4 mile?

Are there amenities like restrooms and healthy food nearby that can allow people to chain destinations and stay out longer?