Review of the

ESMO Congress 2025

Editor’s Pick:

Integrated Multi-omics Approaches in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer for Biomarker and Pathway Discovery

Interviews:

Komal Jhaveri and ESMO President, Fabrice André, discuss the current and future landscape of breast cancer

10 Review of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025, 17th-21st October 2025

Congress Features

23 Expanding the First-Line Option in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Pivotal Trials of Datopotamab Deruxtecan and Sacituzumab Govitecan at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025

François Cherifi

27 AI and Cancer Care

Helena Bradbury

31 The New Frontiers of Personalised Cancer Prevention

Katie Wright Symposium Reviews

36 Emerging Evidence-Based Treatment Strategies in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

47 Navigating a Dynamic Treatment Landscape: Established Therapies and Emerging Modalities for Patients with Lung Cancer

58 Optimising Patient Care: Cutting-Edge Nutritional Strategies in Oncology

71 Exploring New Horizons and Emerging Topics in Squamous Anal Cancer and Colorectal Cancer

82 Abstract Highlights Congress Interview

89 Fabrice André

95 Komal Jhaveri

Infographic

100 The Evolving Biomarker Landscape in GI Cancers

Articles

102 Editor's Pick: Integrated Multi-omics Approaches in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer for Biomarker and Pathway Discovery

Sahli M

116 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Hydropneumothorax: A Rare Case Report with Histopathologic Insights

Fernandez J et al.

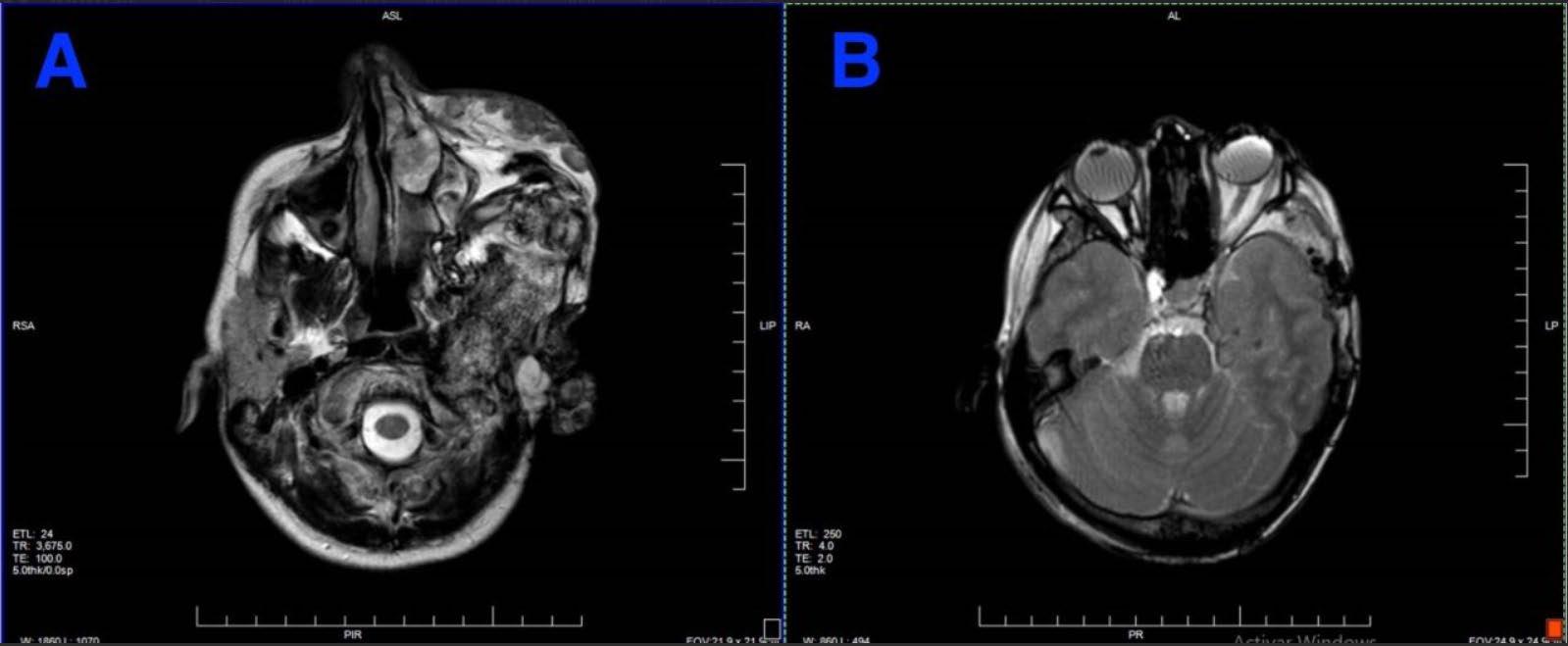

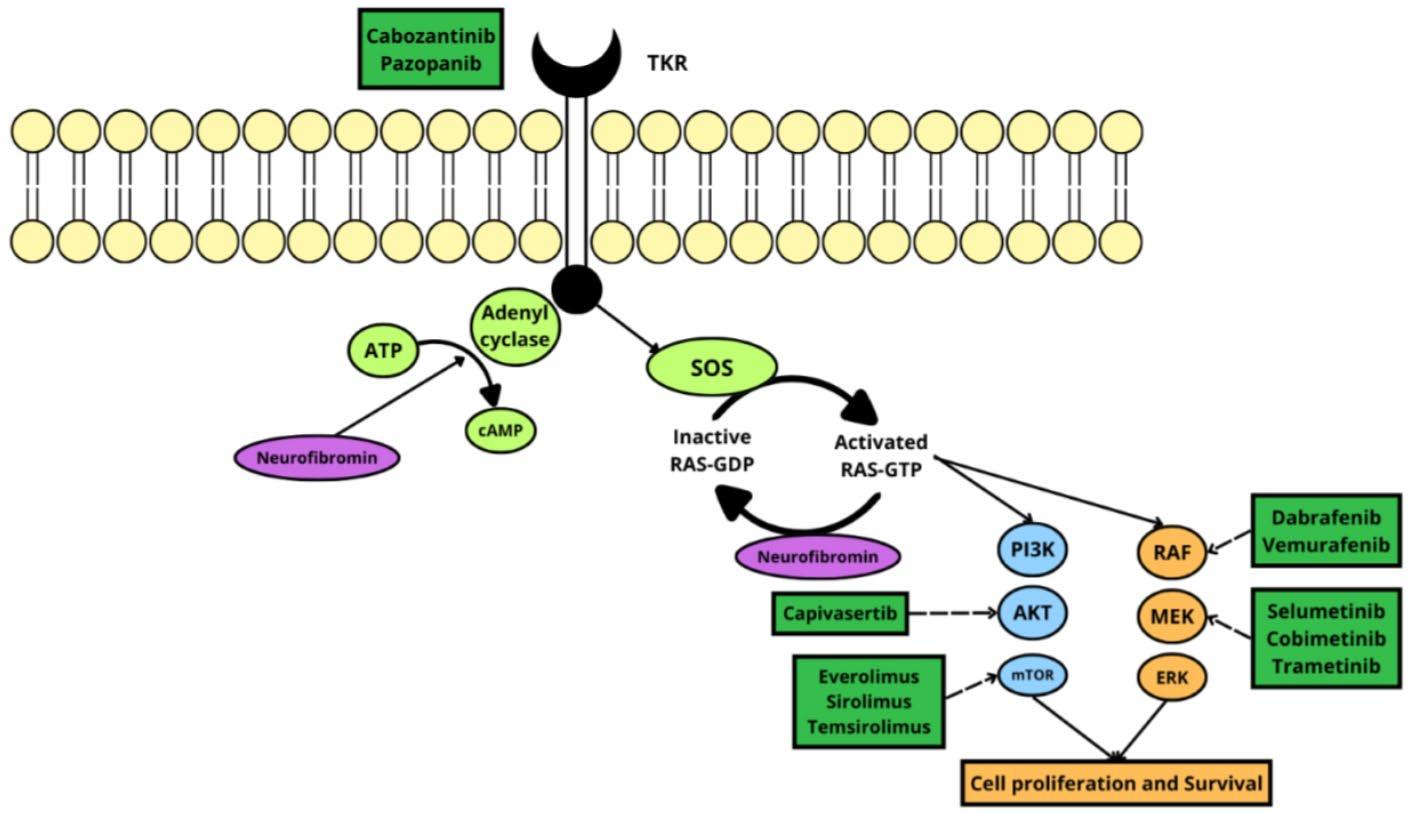

124 Recurrent and Aggressive Solitary Plexiform Neurofibroma with KRAS and AKT1 Alterations: A Case Report

Espinoza IRG et al.

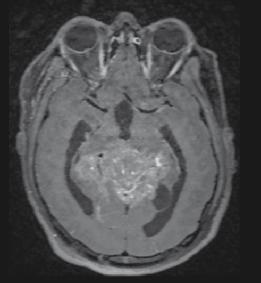

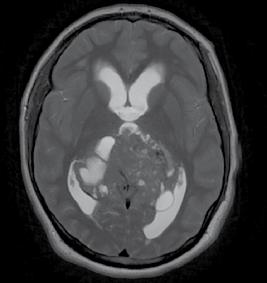

133 Favourable Response of Unresectable Giant Pinealoblastoma After Induction Chemotherapy and Craniospinal Radiotherapy: A Case Report

Laraichi R et al.

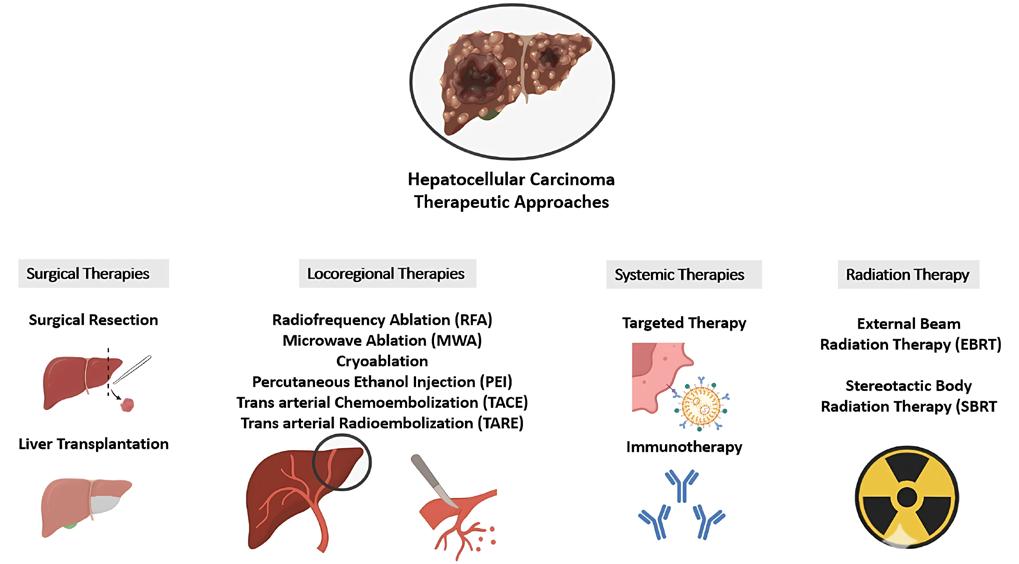

140 Immunotherapeutic Strategies Based on CAR-T Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hemmati N

154 Aggressive Angiomyxoma of Vulva with Term Pregnancy: A Case Report

Khan FH et al.

"Year on year, the society continues to grow and lead innovations in oncology, prioritising education, scientific dissemination, and supporting members in their journey"

Editorial Board

Editor-in-Chief

Prof Ahmad Awada

Chirec Cancer Institute, Brussels, Belgium

Head of the Oncology Department and Director of the Chirec Cancer Institute in Brussels, Belgium. With over 35 years of experience in the field, he is a renowned and trusted expert.

Dr Divyanshu Dua

Canberra Hospital, Australia

Dr Caroline Michie

Edinburgh Cancer Centre & University of Edinburgh, UK

Dr Aniket Mohite

Novo Solitaire Care and Jhangir Hospital, India

Dr Mohammad Akheel

Greater Kailash Hospitals, India

Dr Jyoti Dabholkar

King Edward Memorial Hospital and Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College, India

Dr Jad Degheili

Ibn Sina Hospital, Kuwait

Prof Dr Yves Chalandon

Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland

Dr Javier Cortés

International Breast Cancer Center, Spain

Prof Paul Dent

Virginia Commonwealth University, USA

Dr Abdulmajeed Hammadi

Alyermook Teaching Hospital, Iraq

Prof Antoine Italiano

Institut Bergonié, France

Dr Katarazyna Rygiel

Medical University of Silesia (SUM), Poland

Dr Francesco Sclafani

Institut Jules Bordet, Belgium

Dr Klaus Seiersen

Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

Prof Yong Teng

Georgia Cancer Center, USA

Aims and Scope

EMJ Oncology is an open access, peer-reviewed ejournal committed to helping elevate the quality of practices in interventional cardiology globally by informing healthcare professionals on the latest research in the field.

The journal is published annually, six weeks after the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, and features highlights from this event, alongside interviews with experts in the field, reviews of abstracts presented at the congress, as well as in-depth features on sessions from this event. The journal also covers advances within the clinical and pharmaceutical arenas by publishing sponsored content from congress symposia, which is of high educational value for healthcare professionals. This undergoes rigorous quality control checks by independent experts and the in-house editorial team.

EMJ Oncology also publishes peer-reviewed research papers, review articles, and case reports in the field. In addition, the journal welcomes the submission of features and opinion pieces intended to create a discussion around key topics in the field and broaden readers’ professional interests. EMJ Oncology is managed by a dedicated editorial team that adheres to a rigorous double-blind peer-review process, maintains high standards of copy editing, and ensures timely publication.

EMJ Oncology endeavours to increase knowledge, stimulate discussion, and contribute to a better understanding of practices in the field. Our focus is on research that is relevant to all healthcare professionals in this area. We do not publish veterinary science papers or laboratory studies not linked to patient outcomes. We have a particular interest in topical studies that advance knowledge and inform of coming trends affecting clinical practice in oncology.

Further details on coverage can be found here: www.emjreviews.com

Editorial Expertise

EMJ is supported by various levels of expertise:

• Guidance from an Editorial Board consisting of leading authorities from a wide variety of disciplines.

• Invited contributors who are recognised authorities in their respective fields.

• Peer review, which is conducted by expert reviewers who are invited by the Editorial team and appointed based on their knowledge of a specific topic.

• An experienced team of editors and technical editors.

Peer Review

On submission, all articles are assessed by the editorial team to determine their suitability for the journal and appropriateness for peer review.

Editorial staff, following consultation with either a member of the Editorial Board or the author(s) if necessary, identify three appropriate reviewers, who are selected based on their specialist knowledge in the relevant area.

All peer review is double blind. Following review, papers are either accepted without modification, returned to the author(s) to incorporate required changes, or rejected.

Editorial staff have final discretion over any proposed amendments.

Submissions

We welcome contributions from professionals, consultants, academics, and industry leaders on relevant and topical subjects. We seek papers with the most current, interesting, and relevant information in each therapeutic area and accept original research, review articles, case reports, and features.

We are always keen to hear from healthcare professionals wishing to discuss potential submissions, please email: editorial.assistant@emjreviews.com

To submit a paper, use our online submission site: www.editorialmanager.com/e-m-j

Submission details can be found through our website: www.emjreviews.com/contributors/authors

Reprints

All articles included in EMJ are available as reprints (minimum order 1,000). Please contact hello@emjreviews.com if you would like to order reprints.

Distribution and Readership

EMJ is distributed through controlled circulation to healthcare professionals in the relevant fields across Europe.

Indexing and Availability

EMJ is indexed on DOAJ, the Royal Society of Medicine, and Google Scholar®; selected articles are indexed in PubMed Central®.

EMJ is available through the websites of our leading partners and collaborating societies. EMJ journals are all available via our website: www.emjreviews.com

Open Access

This is an open-access journal in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC 4.0) license.

Congress Notice

Staff members attend medical congresses as reporters when required.

This Publication

Launch Date: 2013

Frequency: yearly Online ISSN: 2054-619X

All information obtained by EMJ and each of the contributions from various sources is as current and accurate as possible. However, due to human or mechanical errors, EMJ and the contributors cannot guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information, and cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions. EMJ is completely independent of the review event (ESMO 2025) and the use of the organisations does not constitute endorsement or media partnership in any form whatsoever. The cover photo is of Berlin, Germany, the location of ESMO 2025.

Front cover and contents photograph: Brandenburg, Germany © Daisha / stock.adobe.com

Editorial Director

Andrea Charles

Managing Editor

Darcy Richards

Copy Editors

Noémie Fouarge, Sarah Jahncke

Editorial Leads

Helena Bradbury, Ada Enesco

Editorial Co-ordinators

Bertie Pearcey, Alena Sofieva

Editorial Assistants

Niamh Holmes, Katrina Thornber, Katie Wright, Aleksandra Zurowska

Creative Director

Tim Uden

Design Manager

Stacey White

Senior Designers

Tamara Kondolomo, Owen Silcox

Creative Artworker

Dillon Benn Grove

Designers

Shanjok Gurung, Fabio van Paris

Junior Designer

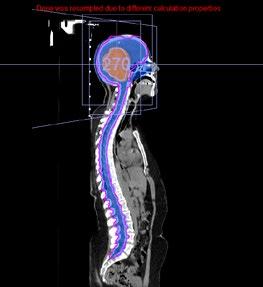

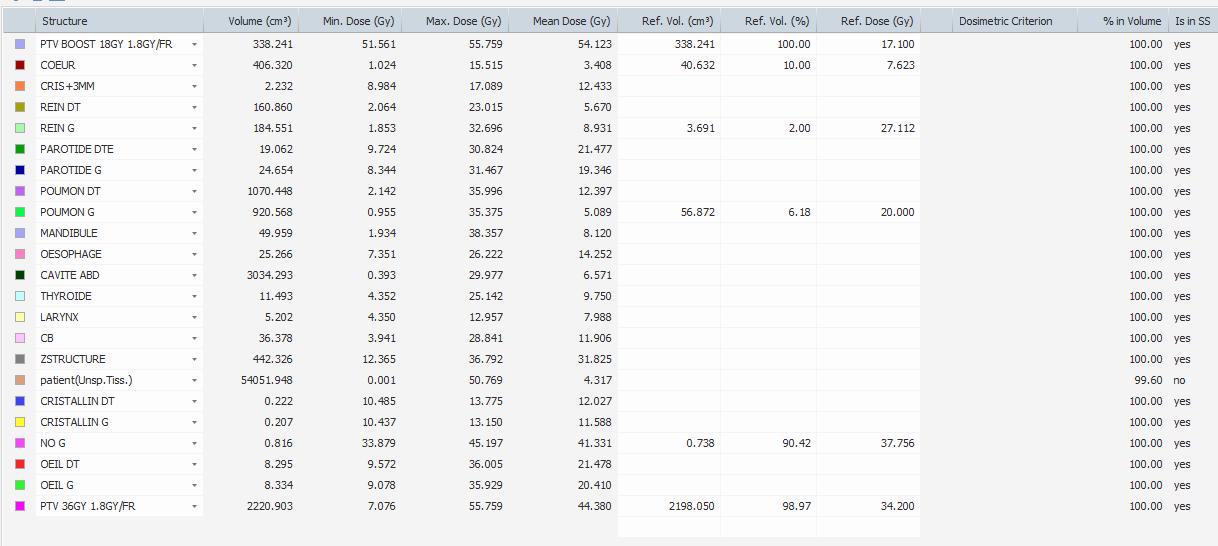

Helena Spicer

Head of Marketing

Stephanie Corbett

Business Unit Lead

Nabihah Durrani

Project Manager

Aghattha Villaflor

Chief Executive Officer

Justin Levett

Chief Commercial Officer

Dan Healy

Founder and Chairman

Spencer Gore

Welcome

Dear Readers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the 2025 issue of EMJ Oncology, bringing you up to date with the key highlights from this year’s European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, which took place in Berlin, Germany. With a record number of attendees and a programme covering the breadth of the field, from new diagnostics and emerging treatments to early diagnosis and prevention, the event was a hub of excitement and insights.

Within this issue, you can find our event coverage, alongside a timely feature exploring the pivotal trial data updates for expanding first-line treatment in triple-negative breast cancer that were presented. Plus, don’t miss our exclusive interview with the ESMO Congress President, Fabrice André, who discusses the Society’s main goals, current challenges in research and patient care, targeted therapies, and much more!

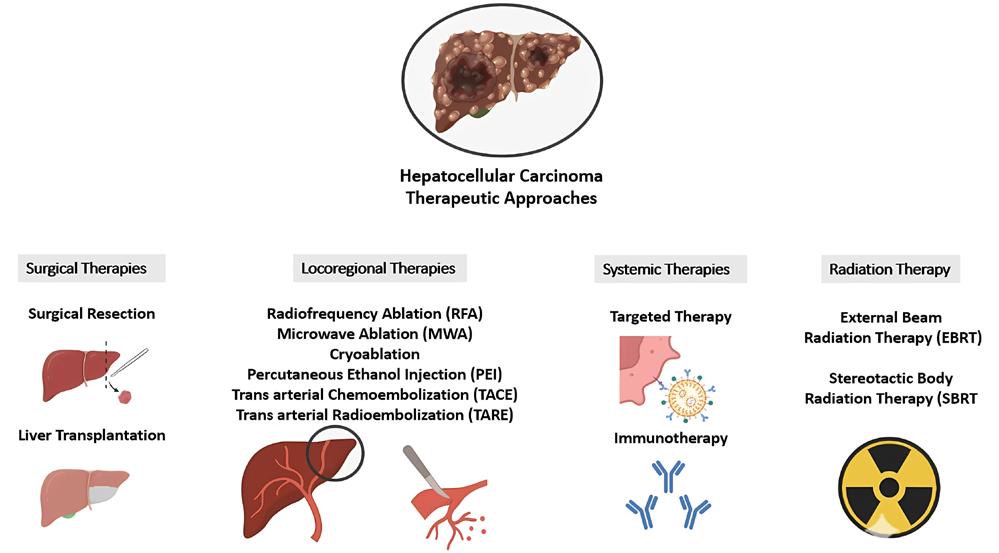

Among our peer-reviewed content, you will find a comprehensive review article summarising emerging T cellbased immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as several interesting case reports, and an infographic focusing on the evolving diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarker landscape of gastrointestinal cancers.

We would like to take this opportunity to thank our Editorial Board, authors, peer reviewers, and interviewees who have contributed to the creation of this issue. We hope you enjoy reading and find useful takeaways for your day-to-day clinical practice and beyond!

Contact us

Editorial enquiries: editor@emjreviews.com

Sales opportunities: salesadmin@emjreviews.com

Permissions and copyright: accountsreceivable@emjreviews.com

Reprints: info@emjreviews.com Media enquiries: marketing@emjreviews.com

Foreword

Welcome to the latest issue of EMJ Oncology, where we present a focused selection of the most compelling developments shaping cancer research and clinical practice in 2025. This edition offers a concise blend of peer-reviewed research, expert insights, and congress highlights that collectively reflect the rapid evolution of oncology.

We are pleased to feature interviews with two leading voices in oncology: Fabrice André, President of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and Komal Jhaveri, an internationally recognised expert in breast cancer and drug development.

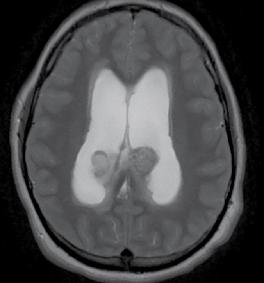

This issue includes six diverse, peerreviewed articles spanning rare case reports and forward-looking reviews. They include a rare presentation of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated hydropneumothorax; a recurrent, aggressive, solitary plexiform neurofibroma with KRAS and AKT1 alterations; and a compelling case of unresectable giant pinealoblastoma responding favourably to induction chemotherapy followed by craniospinal radiotherapy. We also highlight a review of CAR-T cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies in hepatocellular carcinoma, a clinically significant case of aggressive angiomyxoma in term pregnancy, and a multi-omics exploration in non-small cell lung cancer aimed at advancing biomarker and pathway discovery.

While our infographic offers a concise and accessible overview of one of the fastest-moving areas in cancer diagnostics and treatment, this issue also includes a dedicated review of the 2025 ESMO Congress, with features detailing the role of ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, California, USA) and AI in cancer care, emerging advances in personalised cancer prevention, and pivotal data expanding first-line treatment options in triple-negative breast cancer.

This edition offers a concise blend of peer-reviewed research, expert insights, and congress highlights that collectively reflect the rapid evolution of oncology

My sincere thanks to the EMJ team, the Editorial Board, our authors, interviewees, and peer reviewers for their invaluable contributions. I hope you enjoy reading!

Prof Ahmad Awada Head of the Oncology Department and Director of Chirec Cancer Institute, Brussels, Belgium

ESMO 2025

Year on year, the society continues to grow and lead innovations in oncology, prioritising education, scientific dissemination, and supporting members in their journey

Review of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025 Congress Review

Location: Berlin, Germany

Date: 17th–21st October 2025

Citation: EMJ Oncol. 2025;13[1]:10-22.

https://doi.org/10.33590/emjoncol/GBXP9968

THE EUROPEAN Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress

2025 took place in Berlin, Germany, a dynamic epicentre known for its blend of innovation, culture, and historical significance. Home to approximately 3.7 million people, Berlin is Germany’s largest and most diverse city, offering a vibrant backdrop for an international gathering of oncologists, researchers, and healthcare professionals.

Fabrice André, the ESMO President, opened the Congress, highlighting the society’s 50th anniversary. Year on year, the society continues to grow and lead innovations in oncology, prioritising education, scientific dissemination, and supporting members in their journey, now with over 45,000 members. André highlighted the five integral pillars of ESMO: new drugs, strategies of treatment and care, delivery of care, toxicity management, and prevention. Looking to future initiatives, he spotlighted the society’s desire to simplify clinical research, revitalise academic research, and develop individuals’ careers. He stressed the need to invest in personalised prevention and post-cancer care, as well as fostering responsible integration of AI and digital tools, and developing a health economics approach.

So, what are the highlights of this year’s programme? Scientific Co-Chairs Myriam Chalabi, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; and Toni Choueiri, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, took the stage to outline them. The overarching theme of this Congress was one of broken records. A record 5,677 abstracts

were submitted, over 600 more than last year’s 5,030. Attendees also reached an all-time high at 35,676, a steep increase from 33,830 the previous year. Of the 5,677 submitted abstracts, 2,926 were accepted for presentation across presidential symposia (12), proffered papers (158), mini orals (213), posters (1,894), and ePosters (649). In total, the programme featured 2,181 sessions, including three major presidential symposia showcasing practice-changing, practice-informing, and forward-looking research. Read on for an in-depth coverage of the presentations in the presidential symposia.

During the opening ceremony, several prestigious awards recognised individuals for their leadership and contributions to oncology. Thierry Conroy, University of Lorraine, Nancy, France, recipient of the ESMO Award, spoke on the progress made in pancreatic cancer research, improving pancreatic cancer’s 5-year survival from under 3% in 2000 to 13% in 2025. Christina Curtis, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA, recipient of the ESMO Award for Translational Research, presented

on harnessing AI to enhance the prediction of cancer progression and personalise treatment. Rolf Stahel, President of the European Thoracic Oncology Platform –International Breast Cancer Study Group (ETOP IBCSG) Partners Foundation, who received the ESMO Lifetime Achievement Award, reflected on his longstanding commitment to mentorship, teamwork, and the development of initiatives such as the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines and the ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation. The final awardees were Natasha Leighl, University of Toronto, Canada, who received the ESMO Women for Oncology Award, and Glenda Ramos Martinez, Sociedad de Lucha Contra el Cancer, Guayaquil, Ecuador, who received the ESMO Oncologist of the Year Award.

The ESMO Congress 2025 was a landmark event, standing at the forefront of major scientific advances and reaffirming the collective commitment to improving outcomes for patients around the world. Read on for the major takeaways from ESMO 2025, and make sure to join us next year for ESMO 2026 in Madrid, Spain, from 23rd–27th October 2026.

A record 5,677 abstracts were submitted, over 600 more than last year’s 5,030. Attendees also reached an all-time high at 35,676, a steep increase from 33,830 the previous year

Anthracycline-Free Regimen Improves Outcomes in Early HER2+ Breast Cancer

INTERIM

results from the Phase III DESTINY Breast11 trial (291O), presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, indicate that trastuzumab deruxtecan (T DXd) followed by paclitaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab (T DXd THP) significantly increased pathological complete response (pCR) rates compared with the standard anthracycline-based regimen in patients with high-risk HER2-positive early breast cancer (eBC).1

The trial evaluated two T DXd regimens, T DXd alone or T DXd THP, against dose dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by THP (ddAC THP). The openlabel, randomised, multicentre study enrolled adults with untreated high-risk disease (≥T3, node positive [N1–3], or inflammatory HER2-positive eBC).

Treatments were administered in eight neoadjuvant cycles: T DXd (5.4 mg/kg every 3 weeks), T DXd THP (four cycles of T DXd followed by weekly paclitaxel plus 3-weekly trastuzumab and pertuzumab), or ddAC THP (A+C every 2 weeks for four cycles followed by THP). The primary endpoint was pCR (ypT0/is ypN0); secondary endpoints included event-free survival and safety.

By March 2025, 321 patients were randomised to T DXd THP and 320 to ddAC THP. The T DXd THP regimen achieved a pCR rate of 67.3% compared with 56.3% for ddAC THP, an absolute difference of 11.2% (95% CI: 4.0–18.3; p=0.003). Improvements were seen across hormone receptor subgroups: 61.4% versus 52.3% in hormone

receptor-positive and 83.1% versus 67.1% in hormone receptor-negative disease. An early favourable trend for event-free survival was reported (hazard ratio: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.26–1.17).

Safety data showed lower rates of highgrade toxicity with T DXd THP. Grade ≥3 adverse events (AE) occurred in 37.5% (T DXd THP) versus 55.8% (ddAC THP) of patients, and serious AEs in 10.6% (T DXd THP) versus 20.2% (ddAC THP).

Adjudicated interstitial lung disease or pneumonitis occurred in 4.4% (T DXd THP) versus 5.1% (ddAC THP), and left ventricular dysfunction occurred in 1.9% (T DXd THP) versus 9.0% (ddAC THP). No AEs prevented surgery in any treatment arm.

The results suggest that T DXd THP provides superior efficacy and improved tolerability compared with ddAC THP, supporting its potential as an anthracyclinefree neoadjuvant option for high-risk HER2positive eBC. The T DXd-only arm, which halted enrolment following Independent Data Monitoring Committee advice in 2024, will be reported separately.

The trial evaluated two T DXd regimens, T DXd alone or T DXd THP, against dose dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by THP

Trastuzumab Deruxtecan Outperforms Trastuzumab Emtansine in High-Risk HER2+ Early Breast Cancer

IN ONE of the most closely watched trials in early breast cancer, trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) has delivered a major step forward for patients with HER2-positive disease and residual invasive cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Interim findings from the DESTINY-Breast05 Phase III trial, presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, show that T-DXd cut the risk of invasive disease recurrence or death by more than half compared with the long-standing standard of care, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1).2

The open-label trial enrolled 1,635 patients with residual HER2-positive invasive breast cancer following neoadjuvant taxane-based chemotherapy and HER2-targeted therapy. Participants were randomised to receive either T-DXd (5.4 mg/kg) or T-DM1 (3.6 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for 14 cycles. After a median follow-up of nearly 30 months, T-DXd demonstrated a 53% reduction in the risk of invasive disease-free survival events (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.34–0.66; p<0.0001) compared with T-DM1. The benefit was mirrored in disease-free survival results (HR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.34–0.66; p<0.0001).

A trend towards improved brain metastasisfree interval was also observed with T-DXd (HR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.35–1.17), highlighting its potential to delay or prevent central nervous system involvement, which is a growing concern in HER2-positive disease.

Safety outcomes were largely consistent with prior T-DXd studies. Grade ≥3 adverse events occurred in about half of patients in both groups (50.6% with T-DXd versus 51.9% with T-DM1). Interstitial lung disease was more frequent with T-DXd (9.6% versus 1.6%), though most cases were Grade 1–2; two Grade 5 events were reported.

Taken together, these interim data establish T-DXd as a new benchmark for post-neoadjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk HER2-positive early breast cancer, offering not just incremental but transformative improvement in outcomes for this challenging population.

T-DXd demonstrated a 53% reduction in the risk of invasive disease-free survival events compared with T-DM1

Perioperative Enfortumab Vedotin–Pembrolizumab Sets New Standard for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

A STUDY presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress reported that adding perioperative enfortumab vedotin (EV) plus pembrolizumab to surgery significantly and meaningfully improves outcomes in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are cisplatin-ineligible.3

Radical cystectomy combined with pelvic lymph node dissection is the standard treatment for patients with MIBC who are cisplatin-ineligible. Perioperative therapy may improve outcomes in these patients. Therefore, researchers investigated the addition of perioperative EV plus pembrolizumab to standard treatment for MIBC.

The Phase III KEYNOTE-905/EV-303 study evaluated the efficacy and safety of perioperative EV plus pembrolizumab with radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection compared to radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection alone in adult patients with MIBC (T2-T4aN0M0 or T1T4aN1M0) who were cisplatin-ineligible or declined cisplatin. Patients were randomised 1:1 to EV plus pembrolizumab (three cycles of EV 1.25 mg/kg on Day 1 and Day 8 plus pembrolizumab 200 mg on Day 1 every 3 weeks, followed by radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection, then six cycles of EV plus 14 cycles of pembrolizumab) versus control (radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection only). Therapy continued until disease progression, unacceptable adverse events, withdrawal of consent, or completion of planned treatment.

In total, 170 patients were randomised to EV plus pembrolizumab and 174 patients to control. Over 80% of patients were cisplatin-ineligible, as determined by the Galsky criteria. As of 6th June 2025, the median follow-up time was 25.6 months (range: 11.8–53.7). In this study, 149 patients (87.6%) underwent surgery in the EV plus pembrolizumab group and 156 (89.7%) in the control group.

The results revealed that EV plus pembrolizumab significantly improved event-free survival (hazard ratio: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.28–0.57; p<.001), overall survival (hazard ratio: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.33–0.74; p<.001), and pathological complete response rate (57.1% versus 8.6%; estimated difference: 48.3%; 95% CI: 39.5–56.5; p<.001) versus control. Treatmentemergent adverse events occurred in 100% of patients in the EV plus pembrolizumab arm (of which

EV plus pembrolizumab significantly improved event-free survival, overall survival, and pathological complete response rate

71.3% were at least Grade 3), and in 64.8% of patients in the control group (of which 45.9% were at least Grade 3). The most frequent Grade ≥3 adverse events of special interest were severe skin reactions (11.4%) for pembrolizumab and skin reactions (10.8%) for EV.

In conclusion, the addition of perioperative EV plus pembrolizumab significantly improved event-free survival, overall survival, and pathological complete response rate in patients with MIBC who were predominantly cisplatin-ineligible. Additionally, the safety profile of EV plus pembrolizumab was manageable and consistent with prior reports. This is the first perioperative regimen to improve outcomes compared to standard treatment, and may become a new standard of care.

New Study Supports Ivonescimab for Squamous Lung Cancer

A RECENT Phase III study, presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, has shown that ivonescimab combined with chemotherapy significantly improves progression-free survival (PFS) compared with tislelizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with untreated advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer, regardless of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.4

This trial included 532 patients with Stage IIIB–IV disease, randomised equally to receive ivonescimab or tislelizumab alongside paclitaxel and carboplatin for four cycles, followed by maintenance monotherapy. Randomisation was stratified by disease stage and PDL1 tumour proportion score (TPS). The primary endpoint was PFS, assessed by an independent radiographic review committee in line with RECIST v1.1, with overall survival as a key secondary endpoint.

Baseline characteristics were balanced between the two groups, with 63.2% of patients presenting central tumours, 8.8% tumour cavitation, and 17.5% major blood vessel encasement. Ivonescimab plus chemotherapy demonstrated a statistically significant PFS improvement versus tislelizumab plus chemotherapy, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.46–0.78; p<0.0001). Median PFS was 11.1 months in the ivonescimab arm versus 6.9 months in the tislelizumab arm. The benefit was consistent across key subgroups:

patients with PD-L1 TPS <1% had a median PFS of 9.9 versus 5.7 months (HR: 0.55), while those with PD-L1 TPS ≥1% showed 12.6 versus 8.6 months (HR: 0.66). Safety profiles were comparable, with treatmentrelated serious adverse events reported in 32.3% and 30.2% of patients, and Grade ≥3 haemorrhagic events occurring in 1.9% and 0.8%, for the ivonescimab and tislelizumab groups, respectively.

These findings suggest that ivonescimab in combination with chemotherapy may represent a new first-line standard of care for patients with advanced or metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer, offering a meaningful extension in PFS while maintaining a manageable safety profile.

These findings suggest that ivonescimab in combination with chemotherapy may represent a new first-line standard of care

Phase III OptiTROP-Lung04 Trial Shows Sacituzumab Tirumotecan Extends Survival in EGFR-Mutated Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

A PHASE III trial presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress has shown that sacituzumab tirumotecan (sac-TMT), a novel TROP2-directed antibody–drug conjugate, delivers a significant survival advantage over standard platinumbased chemotherapy in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who have progressed on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI).5

The findings position sac-TMT as a promising new treatment option for a population with limited therapeutic alternatives.

The randomised, multicentre study enrolled 376 patients with advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC who received prior third-generation EGFR TKI therapy, with or without platinum-based chemotherapy. Participants were randomised 1:1 to receive either sac-TMT monotherapy or a platinum doublet (pemetrexed plus carboplatin or cisplatin). The study’s primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), assessed by a blinded independent review committee, with overall survival (OS) as a key secondary endpoint.

At a median follow-up of 18.9 months, sac-TMT achieved a median PFS of 8.3 months compared with 4.3 months for chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.39–0.62; p<0.0001). The 12-month PFS rate was 32.3% with sac-TMT versus 7.9% with chemotherapy. OS data also favoured sac-TMT, with a median OS not yet reached versus 17.4 months for chemotherapy (HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.44–0.82; p=0.0006). Adjusted OS analysis confirmed these findings (HR: 0.56; p=0.0002). The objective response rate was 60.6% for sac-TMT compared with 43.1% for chemotherapy, with a median response duration of 8.3 versus 4.2 months, respectively.

Treatment-related adverse events of Grade 3 or higher occurred in 49.5% of patients receiving sac-TMT and 52.2% receiving chemotherapy. Serious treatment-related adverse events were less frequent with sac-TMT (7.4% versus 17.0%), and no

drug-related interstitial lung disease or pneumonitis was reported in either group.

According to the study chair, the results represent a major advancement in the post-TKI treatment landscape, as sacTMT becomes the first TROP2-targeted antibody–drug conjugate to show both PFS and OS superiority over chemotherapy in this setting.

The findings position sac-TMT as a promising new treatment option for a population with limited therapeutic alternatives

Radioligand Therapy Improves Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

AT THE ESMO 2025 Congress, the Phase III PSMAddition trial (LBA6) demonstrated that combining the radioligand [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 with standard androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and an androgen receptor pathway inhibitor (ARPI) significantly improved radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) in patients with prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)positive metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC).6

The trial involved 1,144 adults with treatment-naïve or minimally treated (≤45 days) mHSPC and at least one PSMApositive metastatic lesion detected by [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT. Participants were randomised (1:1) to receive [177Lu] Lu-PSMA-617 (7.4 GBq every 6 weeks, six cycles) plus ADT and ARPI, or standard ADT and ARPI alone. Randomisation was stratified by disease volume (high or low), age (≥70 or <70 years), and primary tumour treatment (yes or no). Patients in the control arm with centrally confirmed radiographic progression could cross over to [177Lu]LuPSMA-617 if eligible.

At the second interim analysis (data cutoff: 13th January 2025; median follow-up: 23.6 months), the primary endpoint was met. rPFS was significantly improved in the [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 arm, with 139 events (24.3%) compared with 172 (30.1%) in the control arm, yielding a hazard ratio of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.58–0.90; p=0.002). Median rPFS was not estimable in either arm. A positive trend in overall survival was observed (hazard ratio: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.63–1.13; p=0.125), with 85 events (14.9%) in the [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 arm versus 99 (17.3%) in the control arm. The objective response rate also favoured the [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 arm at 85.3% (95% CI: 79.9–89.6; n=224) versus 80.8% (95% CI: 74.8–85.8; n=213).

The findings establish that [177Lu] Lu-PSMA-617 added to ADT and ARPI significantly improves rPFS in PSMApositive mHSPC without notable impairment in safety or quality of life

Safety findings were consistent with prior experience. Any adverse event (AE) occurred in 98.4% of patients receiving [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 and 96.6% in controls.

Grade ≥3 AEs were reported in 50.7% versus 43.0% in the control arm, and serious AEs in 31.9% versus 28.7% in the control arm. Dry mouth, mainly Grade 1–2, was the most common AE (41.0% Grade 1 and 4.8% Grade 2 versus 3.4% and 0.4% in controls).

Grade ≥3 cytopenias occurred in 14.4% of patients receiving [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus 5.0% in the control arm. Time to deterioration in quality of life, measured by Functional Assessment of Cancer TherapyProstate (FACT-P) and EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), did not differ meaningfully between groups.

The findings establish that [177Lu]LuPSMA-617 added to ADT and ARPI significantly improves rPFS in PSMApositive mHSPC without notable impairment in safety or quality of life. Long-term followup for overall survival and durability of benefit is ongoing.

Circulating Tumour DNA-Guided Atezolizumab Extends Survival in High-Risk Bladder Cancer

A NOVEL circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA)-guided approach to postoperative therapy has delivered a major advance for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Interim results from the Phase III IMvigor011 trial (NCT04660344), presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, show that adjuvant atezolizumab significantly improves both disease-free and overall survival compared with placebo in patients who test positive for ctDNA following radical cystectomy.7

The global, randomised, double-blind trial enrolled 761 patients with high-risk MIBC and no radiographic evidence of disease. Participants were entered into a year-long ctDNA surveillance programme beginning 6–24 weeks after surgery. Only those who tested ctDNA-positive, indicating the presence of minimal residual disease, were randomised 2:1 to receive either atezolizumab (1,680 mg every 4 weeks) or placebo for up to 12 cycles. Patients who remained ctDNA-negative throughout surveillance received no adjuvant treatment.

After a median follow-up of 16.1 months, atezolizumab reduced the risk of recurrence or death by 36% among patients who were ctDNA-positive compared with placebo (disease-free survival hazard ratio: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.47–0.87; p=0.0047). The overall survival benefit was also statistically significant, with a 41% reduction in mortality risk (hazard ratio: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.39–0.90; p=0.0131).

Median disease-free survival was 9.9 months with atezolizumab versus 4.8 months with placebo, while the 12-month survival rate

reached 85.1% in the atezolizumab arm compared with 70.0% for placebo.

Toxicities were manageable and in line with previous reports for atezolizumab. Grade 3–4 adverse events occurred in 28.5% of atezolizumab-treated patients versus 21.7% with placebo; treatment-related events were reported in 7.3% and 3.6%, respectively.

Fatal treatment-related events were rare (1.8% versus 0%).

Importantly, for the 357 patients who remained persistently ctDNA-negative, the outcomes were excellent: 95.4% were disease-free at 1 year and 88.4% at 2 years, suggesting that these patients may safely avoid adjuvant therapy altogether.

By integrating molecular monitoring with precision immunotherapy, IMvigor011 marks a pivotal step towards personalising postoperative treatment in MIBC, offering therapy only when it’s truly needed, while sparing others from unnecessary toxicity.

By integrating molecular monitoring with precision immunotherapy, IMvigor011 marks a pivotal step towards personalising postoperative treatment in MIBC

Circulating Tumour DNA-Guided De-escalation Reduces Toxicity in Stage III Colon Cancer

PRIMARY analysis of the circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA)-negative cohort from the randomised AGITG DYNAMIC-III trial, presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, has demonstrated that ctDNA-guided de-escalation is feasible and substantially reduces oxaliplatin exposure and adverse events, with outcomes approaching standard management, especially for clinical low-risk tumours.8

The individual benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is not well understood. Therefore, researchers sought to investigate whether post-surgery ctDNA testing could support risk-adjusted treatment selection and guide the de-escalation of adjuvant chemotherapy. The DYNAMIC-III study explored adjuvant chemotherapy deescalation or escalation, informed by postsurgery ctDNA results.

In this multicentre, randomised, Phase II/III trial, patients with Stage III colon cancer who underwent tumour-informed ctDNA testing 5–6 weeks post-surgery were randomised to receive either ctDNA-guided or standard management. For patients who received ctDNAguided management, ctDNA-negative results prompted adjuvant chemotherapy de-escalation: from 6 to 3 months of fluoropyrimidine or observation, from 3 months of doublet to singleagent fluoropyrimidine, or from 6 months of doublet to 3 months of doublet or single-agent fluoropyrimidine. In this study, the primary endpoint was 3-year recurrence-free survival.

ctDNA-guided de-escalation is feasible and reduces oxaliplatin exposure and adverse events, with outcomes approaching standard management

In total, 968 patients were enrolled, of whom 702 (72.5%) were ctDNA-negative. Within this group, 353 patients were assigned to ctDNA-guided treatment management, and 349 to standard management. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 319 (90.4%) patients received ctDNAguided per-protocol de-escalation.

The analysis revealed that ctDNA-guided treatment de-escalation reduced oxaliplatinbased chemotherapy use to 34.8%, compared to 88.6% with standard management (p<0.001). Additionally, ctDNA-guided treatment lowered Grade 3+ adverse events of special interest (6.2% versus 10.6%; p=0.037) and treatmentrelated hospitalisation (8.5% versus 13.2%; p=0.048). However, the analysis did not confirm non-inferiority of ctDNA-guided treatment de-escalation, and the 3-year recurrence-free survival was 85.3% versus 88.1% (97.5% lower CI: –8.0%). The pre-planned subgroup analysis suggested de-escalation may be non-inferior in clinical low-risk tumours (T1-3N1), with a 3-year recurrence-free survival of 91.0% versus 93.2% (97.5% lower CI: –7.2%).

In summary, the results of the DYNAMIC-III study suggest that ctDNA-guided de-escalation is feasible and reduces oxaliplatin exposure and adverse events, with outcomes approaching standard management. Benefit may be seen, particularly for patients with low-risk tumours, but further research is needed to confirm this.

Bemarituzumab Significantly Improves Survival in Gastric Cancer

A RECENT Phase III trial, presented at the ESMO 2025 Congress, has demonstrated that bemarituzumab (BEMA), a first-in-class anti-FGFR2b antibody, significantly improves overall survival (OS) in patients with FGFR2b-overexpressing, non-HER2-positive, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (G/GEJC).9

BEMA functions by blocking oncogenic FGFR2b signalling and engaging antibodydependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In this study, 547 patients were randomised to receive BEMA plus mFOLFOX6 or a matched placebo plus mFOLFOX6, with primary analysis focused on those with FGFR2b ≥10% tumour cell staining. Key secondary endpoints included progression-free survival, objective response rate, and safety.

At the primary analysis, with a median follow-up of 11.8 months, BEMA significantly improved OS compared with placebo, with a median OS of 17.9 months versus 12.5 months and a hazard ratio of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.43–0.86; p=0.005). In the descriptive follow-up analysis, at a median follow-up of 19.4 months, the median OS remained numerically higher with BEMA (14.5 versus 13.2 months), although the treatment effect was attenuated (hazard ratio: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.62–1.08). The safety profile was consistent with expectations, with higher rates of Grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events observed in the BEMA arm, primarily driven by corneal events.

These results suggest that BEMA offers a meaningful survival benefit in patients with FGFR2b-overexpressing G/GEJC, particularly in those with ≥10% tumour cell staining. While the effect was somewhat reduced with longer follow-up, the initial findings support the potential of BEMA as a new targeted therapy in this setting. Further studies, including the upcoming FORTITUDE-102 trial, will help to better define the long-term efficacy and safety of BEMA, offering hope for improved outcomes in this difficult-to-treat patient population.

These results suggest that BEMA offers a meaningful survival benefit in patients with FGFR2b-overexpressing G/GEJC

References

1. Harbeck N et al. DESTINY-Breast11: neoadjuvant trastuzumab deruxtecan alone (T-DXd) or followed by paclitaxel + trastuzumab + pertuzumab (T-DXdTHP) vs SOC for high-risk HER2+ early breast cancer (eBC). Abstract 291O. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

2. Geyer CE et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) vs trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients (pts) with high-risk human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) primary breast cancer (BC) with residual invasive disease after neoadjuvant therapy (tx): interim analysis of DESTINY-Breast05. LBA1. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

3. Vulsteke C et al. Perioperative (periop) enfortumab vedotin (EV) plus pembrolizumab (pembro) in participants (pts) with muscleinvasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are cisplatin-ineligible: the phase III

KEYNOTE-905 study. Abstract LBA2. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

4. Lu S et al. Phase III study of ivonescimab plus chemotherapy versus tislelizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (HARMONi-6). Abstract LBA4. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

5. Zhang L et al. Sacituzumab tirumotecan (sac-TMT) vs platinumbased chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated (EGFRm) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) following progression on EGFR-TKIs: results from the randomized, multi-center phase III OptiTROP-Lung04 study. Abstract LBA5. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

6. Tagawa ST et al. Phase III trial of [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 combined with ADT + ARPI in patients with PSMApositive metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (PSMAddition).

Abstract LBA6. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

7. Powles TB et al. IMvigor011: a phase III trial of circulating tumour (ct) DNA-guided adjuvant atezolizumab vs placebo in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. LBA8. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

8. Tie J et al. ctDNA-guided adjuvant chemotherapy de-escalation in stage III colon cancer: primary analysis of the ctDNA-negative cohort from the randomized AGITG DYNAMIC-III trial (Intergroup study of AGITG and CCTG). Abstract LBA9. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

9. Rha SY et al. Bemarituzumab (BEMA) plus chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic FGFR2b-overexpressing gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer (G/GEJC): FORTITUDE-101 phase III study results. Abstract LBA10. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

Expanding the First-Line Option in TripleNegative Breast Cancer: Pivotal Trials of Datopotamab Deruxtecan and Sacituzumab Govitecan at the European

Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress

2025

Author: *François Cherifi1

1. Medical Oncology Department, Cancer Centre François Baclesse, Caen, France

*Correspondence to francois.cherifi@gmail.com

Disclosure: Cherifi has received grants from Novartis and Gilead, with payment to the institution; consulting fees from Gilead; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Pharmaand; and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Roche, Gilead, and Chugai.

Citation: EMJ Oncol. 2025;13[1]:23-26.

https://doi.org/10.33590/emjoncol/SEBR8422

THIS YEAR, the field of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has witnessed significant advancements in the first line. In June, during the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting 2025, the ASCENT-04 trial proposed sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in combination with immunotherapy at first line for patients who are programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positive. Then, at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025, two highly anticipated studies for patients who are PD-L1 negative were unveiled: the ASCENT-03 trial and the TROPION-Breast02 trial. These studies mark groundbreaking progress in the treatment landscape for TNBC with the advancement of antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) and ‘chemo free’ firstline treatments.

INTRODUCTION

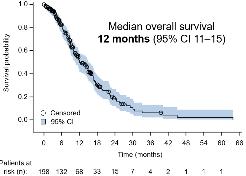

TNBC remains the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, and is characterised by the absence of oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 expression, as well as by a high likelihood of early relapse and visceral spread.1 Despite progress with immune checkpoint inhibitors, response remains variable and unpredictable. Moreover, a substantial proportion of patients with metastatic TNBC are ineligible for PD-L1-based therapy due to PD-L1-negative status or comorbidities.2 For these individuals, chemotherapy has

long represented the default first-line option, offering modest benefit with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of less than 6 months and a median overall survival (OS) rarely exceeding 18 months.1,3

The emergence of ADCs has reshaped therapeutic strategies in pretreated TNBC, with SG and datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) both demonstrating robust antitumour activity in later-line settings. The 2025 congress season marked a major inflexion point for the field: the ASCENT-04/ KEYNOTE-D19 study presented at ASCO 2025 established SG plus pembrolizumab

as a new standard of care for PD-L1positive, previously untreated metastatic TNBC.4 Simultaneously, two Phase III trials presented at ESMO 2025, TROPIONBreast02 (Dato-DXd versus chemotherapy) and ASCENT-03 (SG versus chemotherapy), reported practice-changing results in patients who are PD-L1 negative or immunotherapy ineligible.5,6

The emergence of ADCs has reshaped therapeutic strategies in pretreated TNBC

DATOPOTAMAB DERUXTECAN IN TROPION-BREAST02

The TROPION-Breast02 trial5 was a randomised, open-label, Phase III study evaluating Dato-DXd, a trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2)-directed ADC with a DXd payload, versus the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC for whom immunotherapy was not an option. Eligible patients had received no prior systemic therapy for advanced disease and were randomised 1:1 to Dato-DXd 6 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks or to standard single-agent chemotherapy. The dual primary endpoints were PFS by blinded independent central review and OS.

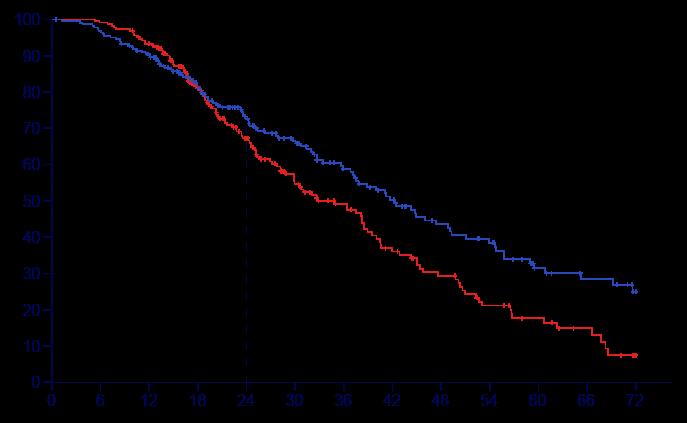

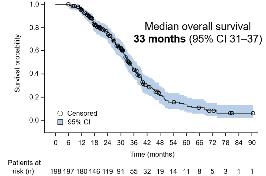

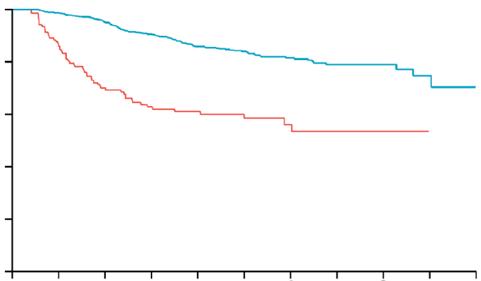

At the August 2025 data cutoff, DatoDXd significantly improved PFS compared with chemotherapy, reducing the risk of progression or death by 43% (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.47–0.69; p<0.0001).

Median PFS was 10.8 months with DatoDXd versus 5.6 months with chemotherapy. The trial also demonstrated a significant OS improvement (HR: 0.79; median OS: 23.7 versus 18.7 months). The objective response rate was 62.5% with Dato-DXd versus 29.3% with chemotherapy, with complete responses in 9.0% versus 2.5% of patients. Median duration of response exceeded 1 year. Safety findings were consistent with prior reports, with stomatitis, nausea, and dry eye as the most common

adverse events. Despite a median treatment duration twice that of chemotherapy, Grade ≥3 toxicities and treatment discontinuations were comparable.

SACITUZUMAB GOVITECAN IN ASCENT-03

The ASCENT-03 trial6 evaluated SG, a TROP2-directed ADC conjugated to SN-38, versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in previously untreated, locally advanced inoperable or metastatic TNBC not eligible for PD-L1 therapy. A total of 558 patients were randomised 1:1 to SG or to chemotherapy (paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine/carboplatin). SG achieved a statistically significant and clinically meaningful PFS improvement, with a 38% reduction in risk of progression or death (HR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.50–0.77; p<0.0001). Median PFS was 9.7 months with SG versus 6.9 months with chemotherapy. Twelve-month PFS rates were 41% and 24%, respectively.

Although OS data were immature, a numerical improvement was observed (median OS: 21.5 versus 20.2 months). Median duration of response was longer with SG (12.2 versus 7.2 months). Safety analysis showed manageable toxicity consistent with prior studies, including neutropenia, diarrhoea, and alopecia. Treatment-related discontinuations were lower with SG (4%) than with chemotherapy (12%).

EVOLVING THERAPEUTIC LANDSCAPE AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The 2025 congress data mark the advent of a new era in TNBC therapy. The parallel success of ASCENT-03 and TROPIONBreast02 represents a decisive shift toward ADCs as front-line standards in TNBC, displacing traditional taxanebased chemotherapy.

ASCENT-04 (SG plus pembrolizumab) and likely TROPION-Breast057 (Dato-DXd in combination with durvalumab) serve PD-L1-positive disease, while SG or DatoDXd monotherapy serve PD-L1-negative

or immunotherapy-ineligible populations, heralding an ADC-dominant paradigm for first-line TNBC management.

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE

The ESMO 2025 data consolidate a unified ADC paradigm in metastatic TNBC. For clinicians, the challenge now lies not in whether to use an ADC, but which ADC to use first. SG and Dato-DXd both target

TROP2, but differ in linker chemistry and payload composition, influencing their pharmacologic profiles and toxicity spectra.8,9 Dato-DXd’s improved tolerability and prolonged PFS make it an attractive option for patients prioritising quality of life, while SG, alone or with pembrolizumab, remains the most clinically validated agent across disease settings. Future research will likely explore long-term outcomes, sequencing and cross-resistance between ADCs, and biomarker-driven personalisation.

References

1. Gennari A et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475-95.

2. Buisseret L et al. The long and winding road to biomarkers for immunotherapy: a retrospective analysis of samples from patients with triple-negative breast cancer treated with pembrolizumab. ESMO Open. 2024;9(5):102964.

3. Punie K et al. Unmet need for previously untreated metastatic triplenegative breast cancer: a real-world study of patients diagnosed from 2011 to 2022 in the United States. Oncologist. 2025;30(3):oyaf034.

4. Tolaney SM et al. Sacituzumab govitecan plus prembrolizumab vs chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated, PD-

L1 positive, advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: primary results from the randomized, phase 3 ASCENT-04/KEYNOTE-D19 study. ASCO Annual Meeting, 30 May-3 June, 2025.

5. Dent RA et al. First-line datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) vs chemotherapy in patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBS) for whom immunotherapy was not an option: primary results from the randomised, phase 3 TROPIONBreast02 trial. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

6. Cortés J et al. Primary results from ASCENT-03: a randomised phase 3 study of sacituzumab govitecan vs chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated metastatic triplenegative breast cancer who are unable to receive PD-(L)1 inhibitors. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

7. Schmid P et al. TROPION-Breast05: a randomized phase III study of Dato-DXd with or without durvalumab versus chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab in patients with PDL1-high locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2025:17:17588359251327992.

8. Cherifi F et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibodydrug conjugates for the treatment of patients with breast cancer. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2024;20(12):45-59.

9. Hong Y et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), a TROP2-directed antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with advanced solid tumors. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2025;DOI:10.1002/ psp4.70118.

AI and Cancer Care

Author: Helena Bradbury, EMJ, London, UK

Citation: EMJ Oncol. 2025;13[1]:27-30. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjoncol/RYOB7684

AI WAS a highlight of the 2025 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, held in Berlin, Germany, with sessions focused on how it works and its potential impact on clinical oncology. One such session, entitled ‘ChatGPT and Cancer Care’ provided a timely exploration of AI’s capabilities in cancer care, as well as the practical and ethical considerations that come with integrating these tools into clinical practice.

LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS AND AI AGENTS IN ONCOLOGY

Jakob Kather, TU Dresden, University of Heidelberg, Germany, opened the session by exploring the world of large language models (LLM) and AI agents in oncology. Stating that AI is already an active part of clinical practice, Kather noted that several AI-driven medical devices have received regulatory approval and are now certified for patient use. Most of these applications focus on image analysis and interpreting X-rays, pathology slides, or endoscopy videos. However, Kather emphasised that each of these systems is built to perform a single, highly specific task on a single data type. This task-specific design limits scalability in clinical settings, where hundreds of different analytic processes occur routinely, each potentially requiring its own dedicated AI system.

First launched in 2022, ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, California, USA) is now a household application, and has transformed the way we receive and consume information. Kather noted the improvements seen in speed, accuracy, and utility of these LLMs over time as they have gathered more information. In terms of use, there are typically three types of interaction with LLMs. The first, and most basic interaction, is called ‘zero-shot’, which comprises a simple question and response, and uses

the embedded knowledge the model was trained on. The second approach, which is more common with recent models, is where LLMs scan the internet for relevant sources to incorporate into the answer. Issues with this, as flagged by Kather, are that it can often pull out-of-date or unrelated information. This can negatively influence the output. Finally, the interaction recommended for enhanced accuracy involves the user asking a direct question with an attached file for the LLM to draw additional information from in its answer.

The medical oncology community must approach emerging technologies with optimism, while upholding the principles of evidence-based medicine

In closing, Kather emphasised that the medical oncology community must approach emerging technologies with optimism, while upholding the principles of evidence-based medicine. He stated that, whenever claims are made about a new technology enhancing our understanding of cancer or improving patient empowerment, it is essential that rigorous clinical trials are conducted to thoroughly test and validate those claims.

LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS FOR DRUG DEVELOPMENT AND CANCER THERAPY

Opening his talk, Loic Verlingue, Centre Léon Bérard, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Lyon, France, shared the benefits that clinical trials offer, namely increasing access to innovative treatments for patients, providing physicians with expertise on new treatments, and improving the economic benefit for societies.

According to Verlingue, there are approximately 9,000 FDA-approved small molecule drugs, but there are thought to be 1,062 potential pharmaceutical compounds. There are also believed to be 20,244 human proteins, but the 3D structure is only known for approximately 6,200 of them, and there are only approximately 2,700 that could act as potential drug targets. As stressed by Verlingue, the use of AI is therefore imperative to predict the structure of proteins and also screen for novel pharmaceuticals.1

As an initial example, Verlingue discussed Cell2Sentence (C2S; Google, Mountain View, California, USA; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA), a novel computational method that converts singlecell gene expression data into textual representations known as ‘cell sentences’. Using this framework, researchers trained a family of LLMs, named C2S-Scale, on

approximately 50 million single-cell profiles and their associated texts.2

To evaluate the platform’s ability to support novel biological discovery, the authors conducted a virtual drug screen using C2SScale. They simulated the effects of roughly 4,000 drug candidates on single-cell data under a specific condition: identifying a drug that could enhance immune signalling in cancer cells that exhibit low interferon levels, which are insufficient on their own to induce antigen presentation. The model identified silmitasertib, a casein kinase 2 inhibitor, predicting that it would enhance major histocompatibility complex Class I-mediated antigen presentation (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C), but only in the context of an already activated immune response. This distinction is important, as it indicates that silmitasertib does not initiate immune activation itself, but rather amplifies it once interferon has already triggered the response.2

Verlingue then raised an important question: while these AI models may be effective at generating new therapeutic drugs, how well do these approaches translate in the clinical setting? Citing a 2024 study,3 and the first analysis of the clinical pipeline of AI-native biotech companies, it was reported that, in Phase 1, AI-discovered molecules had an 80–90% (21/24) success rate of drugs meeting their clinical endpoint, which is higher than the classical success

rate of 40–60%. This is a promising statistic suggesting that AI-generated drug candidates may progress through early clinical stages more efficiently and with greater precision than traditionally developed therapies.

Looking more broadly, Verlingue then discussed the global landscape for oncology clinical trials, and how LLMs can assist in their design and recruitment. Analysing data from 87,748 clinical trials conducted between 2000–2021 across high-income, upper-middle income, lowermiddle income, and low-income countries, a 2024 study reported that, despite an absolute mean annual rise of 266.6 trials, there had been no new trials initiated by 2024.4 These delays may be attributed to several factors, such as patient availability, industry funding, or clinical infrastructure. To address this challenge, he suggested that AI could assist in matching patients to potential clinical trials, helping to increase attrition rates from 8% to over 20%.

Finally, Verlingue spoke on Evo 2 (Arc Institute, Palo Alto, California, USA; Nvidia, Santa Clara, California, USA),5 a new, large-scale, generative AI model that analyses and generates DNA, RNA, and protein sequences to predict protein function, identify pathogenic mutations, and even design new genomes. Trained on

9.3 trillion DNA base pairs from genomes spanning all domains of life, it represents one of the largest biological models ever built, assessing the functional impact of mutations, including in the non-coding regions, splice sites, and clinically relevant genes, without the need for task-specific fine-tuning.

AGENTIC AI IN ONCOLOGY

Closing this timely session, Daniel Truhn, University Hospital Aachen, Germany, summarised the strengths and limitations of AI implementation in oncology. Highlighting findings from a 2023 study on the use of AI chatbots for cancer treatment recommendations,6 Truhn noted a staggeringly high number of inaccuracies. The study reported that 13 of 104 (12.5%)

With the development of more advanced systems, there is now greater assurance and consistency in their answers

responses contained hallucinations, meaning recommendations that did not align with any formal clinical guidelines. Furthermore, while the chatbot provided at least one recommendation for 102 of

the 104 prompts (98%), 35 of those 102 responses (34.3%) included one or more treatments that were not concordant with clinical guidelines.6

Since 2023, have we seen improvements in the use of AI in clinical decision-making in oncology? In a study published this year,7 researchers set out to evaluate an AI agent tailored to interact with and draw conclusions from multiple patient data. It was evaluated on 20 realistic multimodal patient cases and demonstrated an 87.5% accuracy, drawing clinical conclusions in 91.0% of cases and accurately citing relevant guidelines in 75.5% of the time.7

The study reported that 13 of 104 (12.5%) responses contained hallucinations

References

1. Rifaioglu AS et al. Recent applications of deep learning and machine intelligence on in silico drug discovery: methods, tools and databases. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20(5):1878-912.

2. Rizvi et al. Scaling large language models for next-generation single-cell analysis. bioRxiv. 2025;DOI:10.1101/20 25.04.14.648850.

Speaking more broadly, Truhn commented on the tone of AI models and their increasing confidence in generated outputs. He noted that, historically, these models were designed to satisfy the user and could easily alter their responses if challenged. However, with the development of more advanced systems, there is now greater assurance and consistency in their answers.

In closing, Truhn remarked: “You now know about AI, and you have the tools available, or if you don’t, you will soon. What matters is how you use these tools, that you use them responsibly, and that you help us continue to develop them.”

CONCLUSION

At a time where AI is increasingly utilised in all aspects of people’s lives, this session served as a useful reference point. The presentations underscored that, while AI offers faster, more accurate insights, human oversight remains essential to ensure reliability, ethical use, and patient safety. The future of oncology will likely be shaped by a hybrid model, combining the speed and scalability of AI with the expertise and judgment of clinicians.

3. Jayatunga MK et al. How successful are AI-discovered drugs in clinical trials? A first analysis and emerging lessons. Drug Discov Today. 2024;29(6):104009.

4. Izarn F et al. Globalization of clinical trials in oncology: a worldwide quantitative analysis. ESMO Open. 2025;10(1):104086.

5. Brixi GB et al. Genome modeling and design across all domains of life with

Evo 2. bioRvix. 2025;DOI:10.1101/2025. 02.18.638918.

6. Chen S et al. Use of artificial intelligence chatbots for cancer treatment information. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9;(10):1459-62.

7. Ferber D et al. Development and validation of an autonomous artificial intelligence agent for clinical decisionmaking in oncology. Nat Cancer. 2025;6:1337-49.

The New Frontiers of Personalised Cancer Prevention

Author: Katie Wright, EMJ, London, UK

Citation: EMJ Oncol. 2025;13[1]:31-35. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjoncol/DZRT1764

THIS YEAR, the highly anticipated European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025 was held in Berlin, Germany, from 17th –21st October 2025. The Sunday afternoon session, entitled ‘The state-of-the-art of personalised prevention’, brought together leading international experts to explore emerging strategies for reducing cancer risk and improving early detection across multiple cancer types.1 Chaired by Harry de Koning, Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; and Suzette Delaloge, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, the session featured a series of presentations on cutting-edge approaches in cancer prevention. Together, the speakers outlined the current landscape of personalisedcancer prevention and the steps needed to translate research into equitable, effective clinical practice.

LUNG CANCER

Translating Screening Evidence into Public Health

To begin the session, de Koning took the stage to explore the transformative role of low-dose CT in shifting lung cancer diagnosis towards earlier, more treatable stages. Drawing on comparative registry data from the Netherlands, he demonstrated the dramatic redistribution of stage at diagnosis that accompanies the implementation of structured CT screening. In the general population, approximately 50% of lung cancers are detected at Stage IV and only 7% at Stage IA. Under CT screening conditions, this profile reverses, with 50% detected at Stage IA and only 10% at Stage IV. This “stage shift,” de Koning explained, represents the fundamental advantage of CT-based detection over symptom-driven diagnosis or older imaging methods such as chest radiography.

He highlighted key clinical evidence establishing this principle: the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST)2 in the USA and the European NELSON trial.3 Both large-scale

RCTs demonstrated a significant reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality with lowdose CT screening compared to chest X-ray or no screening. Importantly, the NELSON trial achieved even greater mortality reduction, with hazard ratios of 0.76 in males and 0.41 in females after 8 years.

Refining Eligibility and Outcomes

de Koning then presented recently published analyses exploring why NELSON achieved superior outcomes compared to NLST.4 The findings indicate that histologyspecific mortality reductions were a key differentiator: in the NELSON cohort, CT screening significantly reduced mortality from squamous cell carcinoma, a benefit not observed in the NLST trial. This histological insight may explain the European advantage, though de Koning cautioned that further validation is needed.

The same study also examined risk stratification by smoking intensity and cessation status. Contrary to traditional assumptions, individuals with lower cumulative tobacco exposure (<30 packyears) and former smokers (those who quit

≥5 years prior) appeared to benefit equally or even more from screening compared with heavy current smokers. This suggests a broader potential eligibility range for national screening programmes beyond only high-intensity smokers.

Focusing on national projections, de Koning discussed modelling from the Netherlands, estimating the impact of biannual CT screening in high-risk groups.5 Simulations indicate that introducing screening in 2022 could yield an 18% reduction in national lung cancer mortality, representing thousands of prevented deaths over time.

Further analyses demonstrated that early detection directly translates to a survival advantage. In a stage-specific comparison of mortality prevention probabilities,6 earlystage detection (IA–IB) corresponded to an 80% reduction in disease-specific mortality. However, de Koning acknowledged the inevitable trade-off between lives saved and overdiagnosis: based on earlier modelling,7 approximately 500 deaths are prevented per 100,000 screened individuals, alongside 200 cases of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, a balance considered acceptable given the magnitude of benefit.

From Evidence to Implementation

Turning to implementation, de Koning reviewed the European Council’s 2022 recommendations expanding cancer screening programmes to include lung, prostate, and gastric cancers. Several countries, including Croatia, Czechia, Poland, Italy, Hungary, and the Netherlands, have now initiated pilots or national

programmes. The UK, he noted, is a frontrunner with its large-scale Targeted Lung Health Check initiative, having issued 1.8 million invitations and conducted 360,000 scans to date, yielding a 1.3% cancer detection rate with 62% of cases found at Stage I. Encouragingly, preliminary analyses show a 22% reduction in latestage disease, with evidence that screening may narrow socioeconomic disparities, as early-stage detection rates are now higher among the most deprived populations.

Finally, de Koning introduced ongoing and future studies designed to refine screening intervals and population selection, including the 4-IN-THE-LUNG-RUN trial, the SOLACE project (focusing on women and underserved groups), and LAPIN, which aims to evaluate both tobacco and non-tobacco risk factors such as radon exposure. He concluded by emphasising the synergistic role of improved treatment and screening in enhancing survival, referencing recent Dutch data showing marked mortality improvements linked to modern therapies.8

BREAST CANCER

Limitations of Standard Screening

Delaloge began her presentation by outlining the rationale and emerging direction for personalised prevention in breast cancer, emphasising that rising incidence, widening health inequalities, and the limitations of standard screening programmes necessitate a shift in strategy. She noted that global breast cancer incidence has doubled over the

last 30 years, with French epidemiological analyses showing that, while demographic changes account for part of this increase, approximately 50% is attributable to modifiable risk factors linked to lifestyle and environmental exposures. As a result, prevention and screening approaches developed in the 1990s are no longer sufficient, especially given the substantial financial and treatment burden associated with later-stage diagnoses.

Delaloge illustrated the treatment implications of stage at diagnosis, showing that women diagnosed at Stage I require significantly less systemic therapy compared with those at Stages II or III, where extended endocrine therapy, immunotherapies, and targeted agents are increasingly used. The clinical and economic burden of treating later-stage disease, therefore, reinforces the importance of early detection. She highlighted data from France demonstrating that participation in organised screening programmes is associated with lower excess mortality, and importantly, that organised screening reduces the impact of social deprivation on outcomes.9 However, participation in standard mammography screening programmes is declining, particularly among younger women and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, presenting a pressing public health challenge.

The

Multi-Factorial

Framework of Risk Assessment

To address these limitations, Delaloge presented the emerging framework of personalised or ‘interception’ prevention, which combines risk assessment, risk reduction, and tailored early detection.

Germline genetics remains a cornerstone of identifying high-risk groups. Evidence-based strategies for carriers of BRCA1/2 and other high-penetrance genes include MRI from the age of 30 years and, where appropriate, riskreducing interventions.10,11 However, Delaloge emphasised growing attention to polygenic risk scores (PRS), where the cumulative effects of single-nucleotide polymorphisms can markedly refine risk stratification.

Two validated approaches for risk assessment in the general population were highlighted: the integration of PRS with clinical and hormonal risk factors, and AIbased image-derived risk modelling, the latter now being evaluated prospectively in the SMART trial.12,13

Tailored Strategies: Trials and Interventions

The implementation of risk-based screening is currently being tested in major randomised trials. Delaloge highlighted the MyPeBS trial in Europe, which she leads, and the WISDOM trial in the USA.14,15 These studies compare standard age-based screening to risk-adjusted intervals informed by PRS, breast density, and clinical factors. Results, expected in 2027, will determine whether personalised screening reduces rates of Stage II+ disease, while maintaining safety, feasibility, and acceptability.

Delaloge then reviewed risk-reduction strategies, including risk-reducing mastectomy, which may be cost-effective for women aged 30–55 years with a ≥35% lifetime risk;16 endocrine prevention using tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors; and lifestyle interventions, noting evidence that lifestyle modification can produce mortality reductions comparable to some pharmacological approaches.17

She concluded by emphasising the need to integrate prevention and screening, address social inequities, and establish sustainable care pathways to support long-term implementation. Personalised prevention, Delaloge argued, represents not only a scientific evolution but a necessary public health transition.

COLORECTAL CANCER

Aspirin Chemoprevention

Andrew Chen, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA, presented on the emerging strategies for personalised prevention of gastrointestinal and colorectal cancer. He began by emphasising the critical role of colorectal cancer (CRC)

Personalised prevention represents not only a scientific evolution but a necessary public health transition

screening while advocating for more individualised approaches to primary prevention, particularly through the use of aspirin.

Chen outlined two main areas: precision prevention using age-based screening and molecularly guided aspirin therapy for localised CRC. Multiple case-control and cohort studies demonstrate consistent reductions in CRC incidence among aspirin users across diverse populations, supported by five RCTs showing lower recurrence of adenomas or CRC in high-risk individuals. Furthermore, over 50 cardiovascular prevention trials with linked CRC outcomes consistently showed reduced CRC incidence and mortality in aspirin users.18

The CAPP2 trial in patients with Lynch syndrome demonstrated a long-term reduction in CRC risk with aspirin.19 These findings informed the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation supporting low-dose aspirin in adults aged 50–59 years with ≥10% 10-year cardiovascular risk, marking a milestone in cancer prevention via medication.20 However, in 2022, the USPSTF reversed this recommendation, citing insufficient evidence for CRC prevention, largely due to the ASPREE trial, which randomised 19,114 adults aged ≥70 years (or ≥65 for USA minorities) to 100 mg aspirin versus placebo over 4.7 years. ASPREE found increased cancer mortality (hazard ratio: 1.31) in the aspirin arm, without differences in overall cancer incidence.21 Further analysis revealed that

the excess mortality was driven by higher incidence of Stage IV cancers.22

These findings contrast with prior trials, highlighting the importance of age and duration in aspirin prevention. Epidemiologic studies, including the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, indicate that initiating aspirin before the age of 70 years, particularly between 15–69 years, reduces CRC incidence by approximately 25%, whereas starting after 70 years of age offers no benefit.23 Similarly, the Japan Prevention of Atherosclerosis in Diabetes trial confirmed that aspirin’s protective effect is limited in older adults.24 Lifestyle factors also influence benefit: a CRC risk score based on five lifestyle factors predicts that individuals with poorer lifestyles experience the greatest absolute benefit from aspirin.25,26

Molecular-Guided Therapy

Molecularly-guided aspirin therapy is an exciting precision prevention approach. Chen’s group showed that adjuvant aspirin reduced CRC-specific mortality in patients with activating PIK3CA mutations, whereas wild-type tumours did not benefit.27 These findings were validated in the ALASCCA trial26 and supported by the SAC study in Switzerland, which, despite limited enrolment, suggested similar trends in PI3K pathway-altered cancers.28,29 Mechanistically, aspirin may enhance antitumour immunity by blocking thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin

Molecularly-guided aspirin therapy is an exciting precision prevention approach

signalling, rejuvenating exhausted T cells to eradicate PI3K-mutant tumour cells.30

While aspirin use represents a model for personalised CRC prevention, age of initiation, lifestyle, and tumour molecular profile (especially PIK3CA mutations) are critical determinants of possible benefit. Routine aspirin use is justified

References

1. de Koning et al. The state-of-the-art of personalised prevention. ESMO Congress, 17-21 October, 2025.

2. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409.

3. de Koning HJ et al. Reduced lungcancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-13.

4. Welz M et al. A comparative analysis of heterogeneity in lung cancer screening effectiveness in two randomised controlled trials. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):8060.

5. de Nijs K et al. Projected effectiveness of lung cancer screening and concurrent smoking cessation support in the Netherlands. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;71:102570.

6. de Nijs K et al. Stage- and histologyspecific sensitivity for the detection of lung cancer of the NELSON screening protocol—a modeling study. Int J Cancer. 2025;157(11):2248-58.

7. de Koning HJ et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):311-20.

8. de Nijs K et al. Influence of changing patterns in lung cancer treatment and survival on the cost-effectiveness of CT screening: a modeling study. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;88:103446

9. Poiseuil M et al. Impact of organized and opportunistic screening on excess mortality and on social inequalities in breast cancer survival. Int J Cancer. 2025;156(3):518-28.

10. Kotsopoulos J et al. Bilateral oophorectomy and all-cause mortality in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence variations. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(4):484-92.