Microbiology & Infectious Diseases

Research Article:

IDWeek 2025: Hepatitis B Screening Gaps in HIV PrEP Care

Key Discussions, Breakthroughs, and Clinical Updates in HIV Prevention

Research Article:

IDWeek 2025: Hepatitis B Screening Gaps in HIV PrEP Care

Key Discussions, Breakthroughs, and Clinical Updates in HIV Prevention

Welcome 09 Foreword

Congress Review

10 IDWeek 2025 Annual Meeting Highlights, October 21st–24th, 2025

Congress Features

23 IDWeek 2025: Key Discussions and Breakthroughs

Majd Alsoubani

27 HIV Prevention: Clinical Updates from IDWeek 2025

Sara Hockney

Abstract Reviews

33 Evaluation of HIV Virologic Suppression Among Reincarcerated Individuals Within the Illinois Department of Corrections

Fouad et al.

35 Discontinuation Patterns and Virologic Failure Among Persons with HIV Receiving Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine

Antiretroviral Therapy

Hockney et al.

37 Screening and Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Persons Living with HIV in the Illinois Department of Corrections

Schreiber et al.

39 Incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Screening and Detection in People Living with HIV in Custody Within the Illinois Department of Corrections

Stickler et al.

41 Performance of Sputa Gram Stain for the Evaluation of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pneumonia, as Compared to Standard Culture and Multiplex PCR

Sera et al.

44 Blood Culture Stewardship Efforts at a Comprehensive Cancer Center Reduced Isolation of Skin Flora Contaminants Without Compromising Patient Care

Borjan et al.

47 Development of a Severity Scoring System for Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection

Kelly et al.

50 Descriptive Analysis of Positive Strongyloides Serology Across Three Academic Medical Centers

Nagarakanti et al.

52 Incidence and Cumulative Risk Factors for Prolonged Corrected QT Interval in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

Receiving Fluoroquinolone Prophylaxis

Pustorino et al.

Congress Interview

55 Barbara Trautner Interview

59 Tina Tan Features

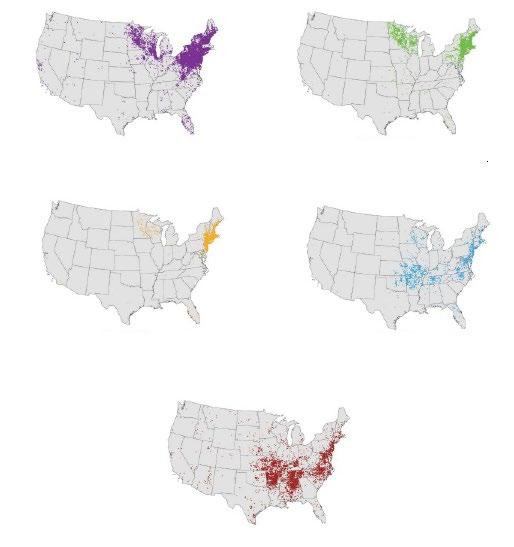

61 Tick, Tick, Boom! An Update on Tickborne Infections in the United States

Karen C. Bloch

70 Cutaneous Histoplasmosis in Patients with HIV: Brief Review

Cano et al. Articles

76 Editor's Pick: Guideline Adherence to Hepatitis B Virus Screening and Vaccination in Patients Prescribed HIV Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis

Ahwad and Badowski

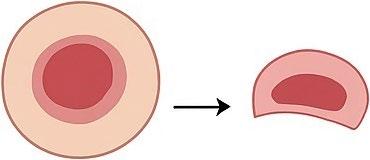

85 Challenges in HIV Monitoring: Insights from Cluster of Differentiation 4 Variability in Resource-Limited Settings

Galo Guillermo Farfán Cano

92 Impact of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG on Weight Loss in PostBariatric Surgery Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial

Nasir et al.

102 Evaluation of Kabul University Students’ Attitude and Knowledge About Antibiotics and Their Use

Dawlatpoor et al.

Dr Shira Doron

Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Dr Shira Doron is the Chief Infection Control Officer for the Tufts Medicine Health System and the Hospital Epidemiologist for Tufts Medical Center, where she is an Infectious Disease physician. She is a Professor of Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr Doron is a member of the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s (IDSA) Practice and Quality Committee and the immediate past chair of the society’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Centers of Excellence subcommittee. She is a long-time consultant to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in the area of antimicrobial resistance prevention, focusing on long-term care facilities. She was a member of Governor Charlie Baker’s Medical Advisory Board during the COVID-19 pandemic. She is also an elected member of the Wellesley Board of Health.

Dr Lisa Akhtar

Ann & Robert H. Lurie

Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Illinois, USA

Dr Michael Angarone

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Dr Shweta Anjan

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Florida, USA

Dr Karen C. Bloch

Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

Dr Syra Madad

New York City Health and Hospitals, USA

Dr L. Silvia Munoz Price

Emerald Coast Infectious Diseases, Fort Walton Beach, Florida, USA

Dr Sandhya Nagarakanti

Mayo Clinic-Arizona, Phoenix, USA

Dr Maurice Policar

New York City Health and Hospitals/Elmhurst, USA

AMJ Microbiology & Infectious Diseases is an open-access, peer-reviewed eJournal committed to helping elevate the quality of healthcare by publishing high quality content on all aspects of microbiology and infectious diseases.

The journal is published annually, 6 weeks after the IDWeek 2025, and features highlights from this congress, alongside interviews with experts in the field, reviews of abstracts presented at the congress, as well as in-depth features on congress sessions. Additionally, this journal covers advances within the clinical and pharmaceutical arenas by publishing sponsored content from congress symposia, which is of high educational value for healthcare professionals. This undergoes rigorous quality control checks by independent experts and the in-house editorial team. AMJ Microbiology & Infectious Diseases also publishes peerreviewed research papers, review articles, and case reports in the field. In addition, the journal welcomes the submission of features and opinion pieces intended to create a discussion around key topics in the field and broaden readers’ professional interests. AMJ Microbiology & Infectious Diseases is managed by a dedicated editorial team that adheres to a rigorous double-blind peer-review process, maintains high standards of copy editing, and ensures timely publication.

Our focus is on research that is relevant to all healthcare professionals in microbiology and infectious diseases. We do not publish veterinary science papers or laboratory studies not linked to patient outcomes. We have a particular interest in topical studies that advance research and inform of coming trends affecting clinical practice in the respiratory field. is an open access, peer-reviewed eJournal committed to helping elevate the quality of practices in microbiology and infectious diseases globally by informing healthcare professionals on the latest research in the field.

Further details on coverage can be found here: www.emjreviews.com/en-us/

Editorial Expertise

AMJ is supported by various levels of expertise:

• Guidance from an Editorial Board consisting of leading authorities from a wide variety of disciplines.

• Invited contributors who are recognised authorities in their respective fields.

• Peer review, which is conducted by expert reviewers who are invited by the Editorial team and appointed based on their knowledge of a specific topic.

• An experienced team of editors and technical editors.

Peer Review

On submission, all articles are assessed by the editorial team to determine their suitability for the journal and appropriateness for peer review.

Editorial staff, following consultation with either a member of the Editorial Board or the author(s) if necessary, identify three appropriate reviewers, who are selected based on their specialist knowledge in the relevant area.

All peer review is double blind.Following review, papers are either accepted without modification, returned to the author(s) to incorporate required changes, or rejected.

Editorial staff have final discretion over any proposed amendments.

We welcome contributions from professionals, consultants, academics, and industry leaders on relevant and topical subjects. We seek papers with the most current, interesting, and relevant information in each therapeutic area and accept original research, review articles, case reports, and features.

We are always keen to hear from healthcare professionals wishing to discuss potential submissions, please email: editorial@americanmedicaljournal.com

To submit a paper, use our online submission site: www.editorialmanager.com/e-m-j

Submission details can be found through our website: www.emjreviews.com/contributors/authors

All articles included in AMJ are available as reprints (minimum order 1,000). Please contact hello@emjreviews.com if you would like to order reprints.

Distribution and Readership

AMJ is distributed globally through controlled circulation to healthcare professionals in the relevant fields.

Indexing and Availability

EMJ is indexed on DOAJ, the Royal Society of Medicine, and Google Scholar®; selected articles are indexed in PubMed Central®

AMJ is available through the websites of our leading partners and collaborating societies. AMJ journals are all available via our website: www.emjreviews.com/en-us/

Open Access

This is an open-access journal in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC 4.0) license.

Congress Notice

Staff members attend medical congresses as reporters when required.

This Publication

Launch Date: November 2025 Frequency: Annually Online ISSN: 2977-4055

All information obtained by AMJ and each of the contributions from various sources is as current and accurate as possible. However, due to human or mechanical errors, AMJ and the contributors cannot guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information, and cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions. EMJ is completely independent of the review event (IDWeek 2025) and the use of the organisations does not constitute endorsement or media partnership in any form whatsoever. The cover photo is of Atlanta, Georgia, USA, the location of IDWeek 2025.

Front cover and contents photograph: Atlanta, Georgia © Jose Luis Stephens / stock.adobe.com

We provoke conversation around healthcare trends and innovation - we also create engaging educational content for healthcare professionals. Join us for regular conversations with physician & entrepreneur, Jonathan Sackier. Listen Now

Editorial

Helena Bradbury, Ada Enesco, Noémie Fouarge, Niamh Holmes, Sarah Jahncke, Bertie Pearcey, Alena Sofieva, Katrina Thornber, Aleksandra Zurowska

Design

Dillon Benn Grove, Shanjok Gurung, Tamara Kondolomo, Owen Silcox, Helena Spicer, Fabio van Paris

Managing Editor Darcy Richards

Design Manager

Stacey White

Head of Marketing

Stephanie Corbett

Creative Director

Tim Uden

Editorial Director

Andrea Charles

Vice President of Content

Anaya Malik

Vice President of Customer Success

Alexander Skedd

Vice President of Business Development

Robert Hancox

Chief Executive Officer

Justin Levett

Chief Commercial Officer

Dan Healy

Founder and Chairman

Spencer Gore

Contact us

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the latest issue of AMJ Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. This publication brings together the latest insights and trends transforming infectious diseases today, combining expert insights, IDWeek 2025 Annual Meeting coverage, and communitydriven learning.

With the dust now settled after IDWeek 2025, the AMJ team has compiled the most exciting takeaways. From evolving strategies in HIV prevention to stewardship innovations, this issue captures key developments in modern clinical practice and real-world challenges that shaped the themes of the gathering.

Our interviews shine a spotlight on two leaders offering firsthand insights on the new urinary tract infection guidelines presented at IDWeek 2025, as well as the challenges of miscommunication around vaccine hesitancy and the importance of trust. The featured articles uncover essential gaps in and opportunities to optimise preventative care in HIV, and how gut-targeted science continues to influence infectious diseases.

Readers will find our congress review packed with award-winning abstracts presented at IDWeek 2025 and discover the emerging research shaping treatment decisions.

My sincere thanks go to the Editorial Board, authors, peer reviewers, presenters, interviewees, and production team, as well as our audience, for your continued trust, intrigue, and contributions.

Editorial enquiries: editorial@americanmedicaljournal.com

Sales opportunities: info@americanmedicaljournal.com

Permissions and copyright: accountsreceivable@emjreviews.com

Anaya Malik Vice President of Content

Reprints: info@emjreviews.com

Media enquiries: marketing@emjreviews.com

The contents of this publication highlight the ongoing contributions from researchers and clinicians dedicated to understanding the complexities of infectious diseases, leading with the breakthroughs from this year’s IDWeek Annual Meeting. We incorporate key developments in modern clinical practice, including new perspectives on long-acting antiretroviral therapy, refinements in screening approaches for high-risk populations, and emerging research in antimicrobial resistance.

The featured articles span a spectrum of microbial and host interactions. The evolving issue of antimicrobial resistance is explored, with a deep dive into how the roles of telehealth, point-of-care testing, and inpatient stewardship are becoming essential to guiding treatment decisions and streamlining care. Notably, the contributions from IDWeek 2025, including clinical updates on HIV treatment and the impact of Mycobacterium tuberculosis screening in correctional settings, provide timely insights that reinforce the importance of continuous innovation in patient care.

The issue also sheds light on critical topics in the treatment of bacterial infections, ranging from the effectiveness of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in post-bariatric surgery patients to new insights on the molecular mechanisms behind Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, and improving the clinical care

of patients receiving HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis with a focus on adhering to established guidelines.

As we look toward the future of infectious disease management, this issue underscores the importance of innovation, collaboration, and adherence to evidence-based practices.

I extend my gratitude to all contributors, authors, and reviewers for their continued dedication to the field.

The contents of this publication highlight the ongoing contributions from researchers and clinicians dedicated to understanding the complexities of infectious diseases

Their work ensures that AMJ Microbiology & Infectious Diseases remains at the forefront of advancing knowledge and fostering discussions that drive healthcare improvements.

Please engage and join us as we continue to enhance patient care and empower excellence in medicine.

Shira Doron Chief Infection Control Officer, Tufts Medicine; Professor of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

The IDWeek 2025 Annual Meeting showcased pivotal advances in infectious diseases, from realworld vaccine data to novel therapeutic approaches

Location: Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Date: October 19th–22nd, 2025

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]:10-22. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/UVIO7409

THE IDWEEK 2025 Annual Meeting showcased pivotal advances in infectious diseases, from real-world vaccine data and innovative stewardship strategies to novel therapeutic approaches reshaping clinical care. This year’s highlights reflect a continued emphasis on optimizing antimicrobial use, improving outcomes for vulnerable populations, and translating evidence into practice.

A NEW real-world study presented at IDWeek 2025 reports that the recombinant zoster vaccine is associated with significantly reduced risks of death and major cardiovascular events in people living with HIV (PLWH). The analysis, conducted by researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, USA, provides new evidence supporting broader health benefits of zoster vaccination in this high-risk population.1

Chronic immune activation in PLWH contributes to an elevated risk of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions, while herpes zoster infection can further intensify these complications. Using the TriNetX Analytics Network (TriNetX, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), investigators performed a retrospective matched cohort study including 3,146 adults aged ≥50 years (mean age: 58.4 years) with HIV and no prior herpes zoster diagnosis. Participants were divided by vaccination status and matched 1:1 on demographics, antiretroviral therapy regimen, comorbidities, psychiatric history, and prior vaccine exposures to ensure balanced comparison groups. After matching, the cohorts were well balanced across key variables.

During a follow-up period ranging from 90 days–7 years (median: 2.89 years in the vaccinated group and 2.78 years in the unvaccinated group), prior zoster vaccination was associated with a 47% lower hazard of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.534; 95% CI: 0.380–0.749; p=0.0002) and a 39% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular

These findings reinforce the importance of comprehensive vaccination strategies as part of holistic care for PLWH

events (HR: 0.614; 95% CI: 0.481–0.783; p=0.0001). A trend toward reduced dementia risk was observed among vaccinated individuals (HR: 0.559; 95% CI: 0.237–1.32; p=0.1783), though this result did not reach statistical significance. No significant differences were found in psychiatric morbidity or Parkinsonism between the groups.

The study demonstrates that zoster vaccination in PLWH is associated with improved long-term survival and lower cardiovascular risk, suggesting potential systemic benefits beyond the prevention of shingles. These findings reinforce the importance of comprehensive vaccination strategies as part of holistic care for PLWH.

Infections remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality after kidney transplantation, and UTIs are particularly common in the early months post-surgery. The study examined whether daily cleansing of the surgical site and perineum with 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloths for 3 months following discharge could reduce infection-related complications. Participants received decolonization kits at discharge, with subsequent monthly kits mailed to their homes, accompanied by detailed instructions from transplant nurses.

The study included 517 adult kidney transplant recipients, of whom 94 received the intervention and 423 served as controls, drawn from the same intervention period and a 2-year pre-intervention period. Outcomes were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for baseline differences.

The study included adult kidney transplant recipients, of whom received the intervention and served as controls

A PRAGMATIC quality improvement study presented at IDWeek 2025 found that post-discharge home decolonization significantly reduced urinary tract infections (UTI) and graft failure in kidney transplant recipients, with a trend toward lower mortality. Conducted by researchers at the University of California, Irvine, USA, the study evaluated a simple, safe, and cost-effective strategy to prevent early post-transplant complications.2 517 94 423

Participants received decolonization kits at discharge, with subsequent monthly kits mailed to their homes

Recipients of the home decolonization intervention experienced significantly lower rates of UTI (19.2% versus 34.8%) and graft failure (0.0% versus 2.8%) compared to non-participants. Deaths were fewer in the intervention group (2.1% versus 6.2%), though this difference did not reach statistical significance. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated higher bacteriuriafree survival at 30, 60, and 90 days posttransplant among participants (88.3%, 83.0%, and 80.9%, respectively) compared with controls (74.5%, 67.1%, and 65.3%; log-rank p<0.004). Adjusted analyses confirmed a significantly lower risk of UTI for participants (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.30–0.82; p<0.004). Adverse events were rare, occurring in approximately 1% of participants.

These findings indicate that post-discharge chlorhexidine gluconate bathing is an effective, low-cost approach to reducing infection-related complications after kidney transplantation. The intervention provides a resistance-sparing alternative to antibiotics, offering a practical strategy to improve outcomes and support graft survival in transplant recipients.

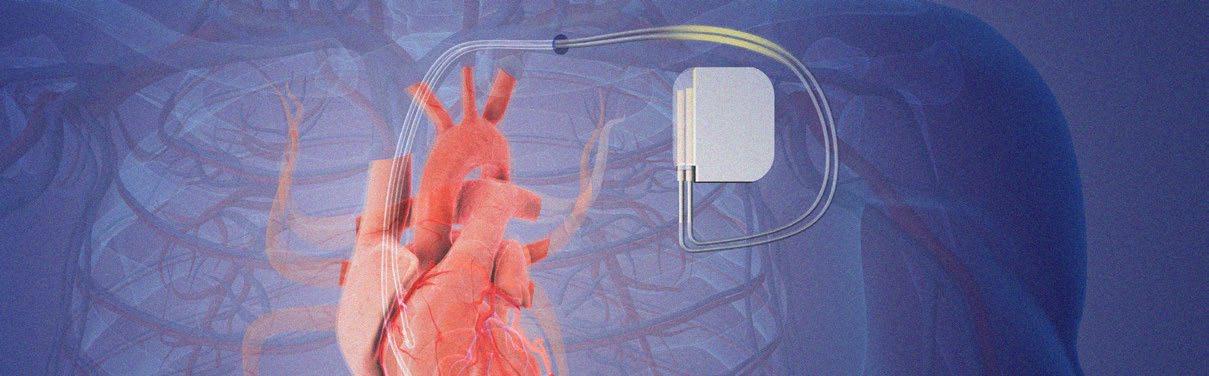

A STUDY presented at IDWeek 2025 found that shorter courses of antibiotic therapy were as safe and effective as longer regimens following the removal of infected cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED). The findings may help refine treatment practices and reduce unnecessary antibiotic use.3

Infections involving CIEDs, such as pacemakers and defibrillators, are the most common reason for lead extraction. While complete removal of the infected device is standard practice, the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment after extraction has not been clearly defined. This study is the first to evaluate how antimicrobial duration affects clinical outcomes in this setting.

Researchers reviewed 747 patient cases between June 2013–December 2023, identifying 79 patients who met inclusion criteria for extraction due to bacteremia or lead-associated infection. Patients were grouped by antibiotic duration of ≤2 weeks or >2 weeks. Baseline characteristics were similar between cohorts. The median duration of antibiotic therapy was 12.6 days for patients receiving ≤2 weeks of antibiotics and 38.6 days for those receiving >2 weeks of antibiotics.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed no significant difference in survival between

the two groups (hazard ratio: 0.693; 95% CI: 0.085–5.652; p=0.438). There were no significant differences in recurrent bacteremia (7% versus 6%; p=0.952), infectious complications (27% versus 30%; p=0.817), hospital length of stay (mean: 9.9 versus 13.3 days; p=0.360), postoperative ICU disposition (0% versus 17%; p=0.112), or rates of cardiac arrest (7% versus 5%; p=0.577).

Relapse or recurrence occurred in five patients, all of whom had infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus (n=3) or Serratia species (n=2) and had either a left ventricular assist device or a valve replacement.

The findings indicate that shorter durations of antibiotic therapy, defined as 2 weeks or less, after CIED lead extraction are not associated with increased mortality or higher rates of recurrent bacteremia. Further studies are needed to determine optimal antibiotic duration and identify risk factors for recurrence in this patient population.

A STUDY from the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, presented at IDWeek 2025, reported high mortality rates among patients with bloodstream infections caused by daptomycin-resistant vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. The research revealed several key prognostic factors and treatment implications for this emerging antimicrobial threat.4

From 2010–2024, investigators analyzed 2,230 vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus bloodstream infection episodes, identifying 120 cases that met the criteria for daptomycin resistance. The median patient age was 67.3 years, with 57.5% being male. Primary bloodstream (45.8%) and urinary tract infections (43.3%) accounted for most cases.

The overall 28-day mortality rate reached 47.5%. Multivariable analysis showed that a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI;

adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 1.30; p=0.02), elevated Pitt bacteremia score (aOR: 1.35; p<0.01), and lower platelet count (aOR: 0.98; p<0.01) were independently linked to increased mortality.

Of the 120 patients, 101 (84.1%) received daptomycin while 19 (15.8%) received linezolid. Patients treated with moderate daptomycin doses (8–11 mg/kg) had higher mortality (aOR: 3.30; p=0.04) than those receiving doses greater than 11 mg/kg. No significant difference in survival was found between high-dose daptomycin and linezolid (aOR: 2.02; p=0.39).

Recurrent bacteremia occurred in about 9% of cases, showing no major variation between treatment groups (15.6% versus 18.2%; p=0.82).

Researchers concluded that high-dose daptomycin, at or above 11 mg/kg, may offer comparable outcomes to linezolid despite laboratory indications of resistance. They emphasized that optimizing dosing and managing underlying risk factors are essential to improving patient survival.

Patients treated with moderate daptomycin doses (8–11 mg/kg) had higher mortality (aOR: 3.30; p=0.04) than those receiving doses greater than 11 mg/kg

USING the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network (TriNetX, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), a new study presented at IDWeek 2025 has found that the use of dalbavancin in people who inject drugs (PWID) with Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with lower mortality and fewer adverse events compared with standard intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy, supporting its role as a safer and more practical treatment option in this high-risk population.5

Treating IE in PWID remains a major clinical challenge. Prolonged IV antibiotic courses are often difficult to complete due to social, behavioral, and logistical barriers. Discharging patients with peripherally inserted central catheters carries risks of line misuse, reinfection, and treatment failure. Dalbavancin, a long-acting lipoglycopeptide that allows for infrequent dosing, is an alternative for those unable to safely receive outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. However, its real-world effectiveness relative to conventional regimens has not been clearly established.

The research team conducted a retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study of adults aged 18 years and older with S. aureus IE and a history of substance use. Patients treated with dalbavancin (n=288) were matched 1:1 with those receiving standard IV antibiotics, including vancomycin, daptomycin, cefazolin, linezolid, or nafcillin (n=288), based on age and sex. The primary outcome was 1-year all-

6.9 %

At 1 year, mortality was significantly lower with dalbavancin at with standard IV antibiotics

compared to

15.6 %

cause mortality, while secondary endpoints included recurrent bacteremia, acute kidney injury, Clostridioides difficile infection, and rash. The median patient age was 38 years, and 49.3% were male. At 1 year, mortality was significantly lower with dalbavancin at 6.9%, compared to 15.6% with standard IV antibiotics, with a risk difference of –8.7 percentage points (95% CI: -13.8–-3.6; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.44; p=0.002). Dalbavancin was also associated with reduced acute kidney injury (11.4% versus 30.6%; HR: 0.32; p<0.001), rash (6.9% versus 12.8%; HR: 0.52; p=0.015), and recurrent bacteremia (52.8% versus 60.4%; HR: 0.36; p=0.001).

These findings indicate that dalbavancin may provide an effective and safer alternative to traditional IV therapy for S. aureus IE in PWID. Incorporating dalbavancin into clinical pathways could improve adherence, reduce hospital readmissions, and lessen complications related to IV access.

MMBV assists clinicians in distinguishing bacterial from viral infections

RESEARCH presented at IDWeek 2025 has demonstrated that integration of the MeMed BV® (MMBV; MeMed, Tirat Carmel, Israel) host-response test into clinical decision-making in urgent care centers (UCC) is associated with improved patient outcomes, including reduced hospitalization rates within 7 days of discharge.6

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing remains a significant challenge in UCCs, where diagnostic uncertainty is often high due to limited consultation time and restricted access to diagnostic tools. MMBV, an FDAcleared test that evaluates the host immune response by combining levels of three immune proteins into a bacterial likelihood score, assists clinicians in distinguishing bacterial from viral infections. The test demonstrates a negative predictive value greater than 98%, making it a reliable aid in guiding antibiotic prescribing decisions and enhancing antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

This retrospective analysis assessed realworld data from 3,758 adult patients tested with MMBV during visits to 10 UCCs between April–December 2022. Of these, 59.3% were female and the median age was 42 years (interquartile range: 31–58). Bacterial results were reported in 858 patients (22.8%), viral in 2,404 (64.0%), and equivocal in 496 (13.2%). It was also revealed that patients with bacterial MMBV results were older

(median: 51 versus 39 years) and more frequently diagnosed with lower respiratory tract infections (29.6% versus 9.4%). Among those with bacterial results, antibiotic treatment was associated with significantly fewer hospitalizations within 7 days (7.3% versus 36.1%; p<0.001). For viral results, withholding antibiotics correlated with a lower rate of lower respiratory tract infection diagnosis (4.2% versus 29.5%) and fewer hospitalizations (2.5% versus 5.3%; p=0.003).

This study shows that the incorporation of MMBV into urgent care workflows appears to improve clinical outcomes while supporting appropriate antibiotic prescribing. By providing clinicians with timely hostresponse insights, MMBV may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, hospital admissions, and associated healthcare costs. Further prospective studies could evaluate its integration into broader infection management protocols and explore long-term impacts on antimicrobial resistance trends.

PERSONS experiencing homelessness (PEH) face a disproportionately high burden of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and often encounter significant barriers to diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment. Conventional point-of-care (POC) HCV antibody tests only indicate prior exposure rather than active infection, creating delays in linking individuals to care. The Cepheid Xpert HCV test (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA) offers a rapid method to detect active HCV RNA, allowing health providers to diagnose infection and begin treatment more quickly. A recent study, presented at IDWeek 2025, evaluated the use of the Xpert HCV test within a street medicine model to improve HCV care among PEH.7

From November 2024–February 2025, weekly street medicine outreach runs were conducted. Individuals were offered testing using a finger-stick blood sample, which was analyzed for both HCV antibody and active HCV RNA on a POC Cepheid Xpress system (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA). Those who tested positive for HCV RNA received confirmatory bloodwork, including viral load and genotype testing, and were assessed for eligibility for simplified treatment with directacting antivirals. Eligible participants were provided medication directly on a weekly or biweekly basis, accompanied by adherence support. Viral load was measured again at the end of treatment to assess response.

Among the individuals tested, 20 were HCV antibody-positive and 13 had active infection. Twelve were able to complete additional bloodwork, and all met guideline-based criteria for simplified direct-acting antiviral therapy. Nine patients began treatment, four completed therapy, and three achieved undetectable viral RNA at the end of treatment. No HIV or hepatitis B co-infection was observed. The average time from testing to initiation of treatment was approximately 20 days.

These findings show that rapid RNA-based POC testing can successfully identify active infection and facilitate timely treatment among PEH. Integrating such testing into

street medicine can meaningfully advance HCV elimination efforts in highly marginalized populations.

A RECENT study, presented at IDWeek 2025, described how a national shortage of blood culture (BCx) supplies prompted the implementation of targeted mitigation measures at a large academic medical center.8

BCx contamination rates also decreased from 1.96% to 1.66%, suggesting improved diagnostic stewardship

These measures aimed to decrease unnecessary BCx use while evaluating potential effects on antibiotic prescribing practices, contamination rates, and key outcomes related to sepsis management. Clinicians were supported through electronic clinical decision support tools that offered soft stops on repeat cultures, required acknowledgement for repeat BCx performed within 48 hours, and suggested alternative testing options. Education efforts were directed across the institution, with particular focus on areas with historically high BCx utilization, including the emergency department and oncology units.

This retrospective pre- and post-intervention study compared data from a pre-shortage period (July 2023–May 2024) to the shortage period (July 2024–November 2024). The primary outcome was antibiotic days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days. Secondary outcomes included the number of blood cultures obtained, sepsis core measure performance, length of stay, inpatient mortality, and rates of blood culture contamination. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

BCx utilization declined significantly during the shortage, decreasing from a median of 1,846 to 1,205 cultures. Despite concerns that reduced culture availability might lead to increased empiric antibiotic use, overall antibiotic consumption remained stable. Notably, in the emergency department, use of vancomycin, cefepime, and ceftriaxone decreased significantly. Patient outcomes were not negatively affected: inpatient mortality remained unchanged, and length of stay showed a modest reduction. BCx contamination rates also decreased from 1.96% to 1.66%, suggesting improved diagnostic stewardship.

These findings indicate that targeted mitigation strategies can effectively reduce BCx use during shortages without compromising antibiotic stewardship or sepsis care. The reductions in selected antibiotics and contamination rates further support careful culture utilization as a component of high-quality clinical practice.

These findings indicate that targeted mitigation strategies can effectively reduce BCx use during shortages

NEW RESEARCH presented at IDWeek 2025 has provided the first largescale, real-world evidence of how the 2021 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) treatment guidelines have reshaped clinical practice, improved patient outcomes, and influenced healthcare costs across the USA.9

The 2021 guideline update recommended fidaxomicin over vancomycin as the preferred first-line therapy for both initial and recurrent CDI, and bezlotoxumab as an adjuvant treatment for high-risk patients. In this new analysis, Angela Wu and colleagues from the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA, examined over 1.2 million CDI encounters from 2018–2024 using the Epic Cosmos database, comparing treatment patterns and outcomes before and after the guideline release in June 2021.

Following implementation, the researchers observed clear shifts in prescribing behavior: fidaxomicin use tripled from 3.1% to 9.6%, vancomycin use rose slightly, and bezlotoxumab prescriptions increased fivefold, while metronidazole use dropped by nearly half. Importantly, these changes coincided with a measurable clinical benefit. The odds of 30-day CDI recurrence fell by 4% immediately after the guideline update (odds ratio: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94–0.97; p=0.001), and

recurrence trends flattened in the months that followed.

While hospital length of stay increased briefly after implementation, it declined significantly over time as practices stabilized. However, the financial impact was notable: total monthly CDI-related costs surged by nearly 20 million USD in the immediate postguideline period, largely due to the higher costs of fidaxomicin and bezlotoxumab. Despite this, the study found no ongoing upward cost trend in the following years.

The authors concluded that adoption of the 2021 IDSA/SHEA CDI guidelines has led to fewer recurrences and improved care outcomes, but also emphasized the importance of addressing the economic burden associated with newer, higher-cost therapies. These findings underscore the balance between evidence-based advances and cost sustainability in infectious disease management.

THE LATEST research presented at IDWeek 2025 suggests that shorter antibiotic courses may be just as effective, and potentially safer, for hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections (UTI) under the new Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) definition of uncomplicated UTI.10

The forthcoming IDSA complicated UTI guidelines redefine complicated UTI as infections extending beyond the bladder, meaning that many patients previously classified as having complicated infections would now fall under the uncomplicated category. This reclassification expands the group of patients eligible for shorter antibiotic treatment durations, a shift that could significantly impact prescribing practices and antimicrobial stewardship nationwide.

Researchers analyzed data from 68 hospitals in Michigan, USA, collected between November 2021–November 2024, encompassing 13,784 hospitalized patients with UTI, of whom 1,854 met the new uncomplicated UTI definition. Using a target trial emulation framework and rigorous statistical adjustments, the study compared outcomes between patients receiving short (3–5 day) and long (6–14 day) antibiotic regimens.

Results showed no significant difference in 30-day recurrence rates between the two treatment durations (odds ratio: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.45–1.17). However, patients treated with shorter courses experienced fewer antibioticrelated adverse events (odds ratio: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.12–0.95). Common characteristics, including comorbidities and infection severity, were similar between groups, and ceftriaxone was the most frequently prescribed empiric antibiotic.

The findings reinforce growing evidence that short-course antibiotic therapy is both effective and safer for patients with UTIs that do not extend beyond the bladder. By minimizing antibiotic exposure without compromising efficacy, this approach could help curb adverse drug effects and reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance.

The authors concluded that the results provide strong real-world support for shorter antibiotic durations in patients meeting the new uncomplicated UTI definition, aligning with the IDSA’s evolving recommendations for optimized, evidence-based antimicrobial use.

1. Dehghani A et al. Zoster vaccination in people living with HIV is associated with reduced mortality and cardiovascular risk: a real-world matched cohort study. Oral abstract P-402. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

2. Nam HH et al. Home decolonization to decrease UTI, graft failure, and death after renal transplantation (PROTEKT: PROTEction after Kidney Transplant): a pragmatic quality improvement study. Oral abstract P-295. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

3. Xiao EY et al. Shorter duration of antimicrobial therapy is noninferior for cardiovascular implantable electronic device associated systemic infections. Abstract 453. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

4. Lin WT et al. High dose daptomycin shows non-inferior outcome compared to linezolid in patients with daptomycin and vancomycin resistant enterocci bloodstream infection. Abstract 367. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

5. Ssentongo P et al. Comparative effectiveness of dalbavancin versus standard therapy for staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in people who inject drugs: a retrospective, propensity-matched cohort study using real-world data. Abstract 451. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

6. David SSB et al. Host-response testing to guide antibiotic prescription: association between MeMed BV® results and clinical outcomes in an urgent care network. Abstract 148. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

7. Crooker KG et al. Implementation of novel point-of-care hepatitis C RNA platform and clinical characteristics of treatment in persons experiencing homelessness in Detroit, Michigan. Abstract 199. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

8. Kusnik N et al. Intended and unintended consequences of a blood culture bottle shortage. Abstract 432. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

9. Wu et al. Real-world impact of the 2021 IDSA/SHEA CDI guidelines: shifts in treatment, outcomes, and healthcare costs. Abstract 194. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

10. Steinberger M et al. A target trial emulation of short vs long antibiotic duration for the new definition of uncomplicated UTI. Abstract 376. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

Author: *Majd Alsoubani1,2

1. Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

2. The Stuart B. Levy Center for the Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance, School of Medicine, Tufts University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

*Correspondence to Majd.Alsoubani@tuftsmedicine.org

Disclosure: Alsoubani has received grant funding from Carb-X as a principal investigator.

Keywords: Health access, HIV prevention, IDWeek 2025, public health.

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]:23-26. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/RVPF8742

ATLANTA, Georgia, USA, homebase for the CDC and a fitting stage for public health discourse, welcomed thousands of clinicians, scientists, pharmacists, and trainees for IDWeek 2025. The 4-day meeting combined late-breakers, pragmatic debates, hands-on workshops, and the ever-busy BugHub stages.

Javier Muñoz, actor and advocate, opened IDWeek 2025 with a deeply personal reflection on living with HIV. His story brought data to life, grounding science in real human experience and reminding everyone that innovation only matters when it reaches the people who need it most.

The Opening Plenary embraced the spirit of IDWeek’s host city, with speakers highlighting the resilience and dedication of public health professionals at the CDC and across partner organizations. The theme, 'Reflection and renewal: advancing public health in challenging times', struck a balance between realism and optimism. It acknowledged workforce fatigue and funding challenges while emphasizing

readiness, stronger communication, and the power of implementation science to drive progress.

From there, speakers emphasized that preparedness is not just about responding to the next emergency, but a constant commitment to building surveillance, communications, and clinical capacity. They called for continued vigilance in vaccine confidence and safety, practical approaches to antimicrobial stewardship, and a sustained focus on equity and access to care.

IDWeek’s awards underscored the community’s depth and breadth. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recognized leaders across clinical care, research, mentorship, and public health. Awardees included John Boyce, J.M.

Boyce Consulting, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, who received the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) award for his career-long impact on hand hygiene research and preventing healthcare-associated infections; Walter Orenstein, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, who was awarded the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) award recognizing decades of work shaping U.S. and global immunization policy; and David Ha, Stanford, Menlo Park, California, USA, who accepted the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP) 2025 Outstanding Clinician Award. The IDSA Society Citation Award was presented to the IDSA Chief Executive Officer, Christopher D. Busky, Arlington, Virginia, USA, for nearly a decade of steady leadership of the Society and the IDSA Foundation.

A signature moment was the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA)’s Transformative Leader Award for Demetre Daskalakis, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, who was recognized for 2 decades of work spanning his 'status-neutral' prevention model in New York City, USA, to national leadership roles at the CDC and the White House. His acceptance speech framed a bracing moral call to action. Daskalakis began by reminding the room that “vaccines, antiretroviral therapy, antimicrobials, [and] infectious-disease care, these are all miracles,” born of centuries of science and dedication. An effective response to the current challenges, he argued, rests on “three pillars: science, political will, and co-creation with communities.” Using a striking metaphor, he described today as a kind of “dark age,” urging the field to be the renaissance. When those pillars are strained, the answer is not a retreat but transformative leadership at every level, in clinics and pharmacies, in public health agencies, and in policy. The standing ovation that followed reflected both the moment and the messenger: an equityfirst leader whose recent resignation from the CDC over the politicization of vaccine policy has made his appeal for courage and community even more resonant.

IDSA’s top lifetime honor, the IDSA Alexander Fleming Award for Lifetime Achievement, went

to Cynthia L. Sears from The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. She was celebrated as a world-renowned physician-scientist, mentor, and leader. The Society noted her career as one that has embodied the virtues the Fleming Award exists to recognize: scientific excellence, mentorship, and service, making her a fitting recipient to open IDWeek’s celebration of the field’s most enduring contributors.

Paige Alexander, CEO of The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, framed infectious diseases within broader issues of institutional trust and global health. The Carter Center was founded by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and former First Lady Rosalynn Carter on a very simple premise: “Waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope.” From that starting point, the Center has helped 22 countries eliminate at least one neglected tropical disease, distributed more than 1.1 billion doses of medicine, provided sight-restoring surgery to roughly one million people, and

IDWeek’s awards underscored the community’s depth and breadth

monitored more than 125 elections in 48 countries. Most dramatically was the Guinea worm eradication, cutting cases from an estimated 3.5 million a year in 21 countries to just 15 human cases in 2024 through partnerships with local governments and communities. The Carter Center perspective underscored the importance of public trust: “Health security is impossible without public trust; if people don’t believe you, they won’t drink the filtered water, they won’t take the medicine, and they won’t show up for vaccines.”

In the closing minutes of the Plenary, speakers previewed a new collaboration between the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) and a journal house to publish rapid “Public Health Alerts,”

intended to disseminate vetted outbreak and safety signals at Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)-like speed.

The Annual Meeting included Meet-theProfessor, career fair, and mentorship sessions, which emphasized the real investment in building a new generation of infectious disease clinicians. The most infectious event, the IDBugBowl, kept everyone on the edge of their seats, with the University of Alabama clinching the win on the final Jeopardy-style question.

The big themes of IDWeek revolved around prevention first. The clinical efficacy of twice-yearly lenacapavir pre-exposure prophylaxis in women, and the very high efficacy in men and gender-diverse people, was highlighted in several discussions.1,2 Additional favorable data on safety and efficacy in youth, pregnant people, and people who use substances were presented. Now that lenacapavir is approved by the FDA, the pressing next step is focusing on accessability and affordability. How will lenacapvair pre-exposure prophylaxis be delivered, paid for, and reach the individuals least likely to stay in care?3

A second theme was respiratory protection. Real-world data on the respiratory syncytial virus vaccination in older adults and patients with immunocompromising conditions reassured clinicians that these vaccines prevent hospitalization and critical illness.4,5 However, the protection wanes over time, especially in immunocompromised people.6

Maternal–infant prevention also got a big boost: a Phase 4, randomized, openlabel study showed that infants have high neutralizing antibody levels whether the mother was vaccinated in pregnancy, the infant received nirsevimab after birth, or both. There were no safety concerns across the board.7

IDWeek emphasized the need for healthcare that finds patients, not the other way around. Inpatient programs that screen for hepatitis C and start direct-acting antivirals at the bedside showed that they can capture people who would otherwise be lost to care after discharge.8 Telehealth-based treatment, as well as point-of-care testing and treatment initiation, were also ways to reach patients, including people who use drugs or those with unstable housing.9

Lastly, on the inpatient infectious diseases practice side, the dalbavancin DOTS trial offered another option for the treatment of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with a long-acting agent, sparing patients from peripherally inserted central catheter lines and the logistics of home intravenous therapy.10 New options for S. aureus bacteremia could be on the horizon. In a recent Phase 2a trial, an intravenous bacteriophage cocktail, AP-SA02, with best available therapy showed significantly higher clinical cure rates, earlier resolution of infection, and shorter hospital stays, demonstrating early efficacy signals and a favorable safety profile.11 The PIVOT-PO trial presented the safety and efficacy data of oral tebipenem pivoxil hydrobromide (oral carbapenem) compared with imipenemcilastatin for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infection. Tebipenem showed similar efficacy, including in participants with extended-spectrum beta-lactamaseproducing Enterobacterales.12

References

1. Bekker LG et al.; PURPOSE 1 Study Team. Twice-yearly lenacapavir or daily F/TAF for HIV prevention in cisgender women. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(13):1179-92.

2. Kelley CF et al.; PURPOSE 2 Study Team. Twice-yearly lenacapavir for HIV prevention in men and genderdiverse persons. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(13):1261-76.

3. Fairhead C et al. Generic lenacapavir HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis could be produced for $25 per person per year. Presentation 174. IDWeek, October 1922, 2025.

4. Link-Gelles R et al. Effectiveness of RSV vaccines in older adults in the United States, VISION Network, 2023-2025. Presentation 221. IDWeek, October 1922, 2025.

5. Mayer EF et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the mRNA-1345

RSV vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients aged ≥18 years. Presentation 223. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

6. Hage C et al. Durability of RSV antibodies following RSV vaccination in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2025;25(8):S98-9.

7. Rostad CA et al. The immunology and safety of maternal RSV vaccination, infant nirsevimab immunization, or both products- interim analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Presentation 225. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

8. McCrary LM et al. large scale implementation of opportunistic HCV treatment during hospitalization in a US tertiary care hospital. Presentation 201. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

9. Di Paola A et al. Highway to health: mobile pharmacy and clinic providing hepatitis C testing and treatment. Presentation 198. IDWeek, October 1922, 2025.

10. Turner NA et al. Dalbavancin for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: the DOTS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2025;DOI:10.1001/ jama.2025.12543.

11. Miller LG et al. A phase 2a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of an intravenous (IV) bacteriophage cocktail (APSA02) vs. placebo in combination with best available antibiotic therapy (BAT) in patients with complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Presentation 549. IDWeek, October 1922, 2025.

12. Hong DK et al. Oral tebipenem pivoxil hydrobromide versus intravenous imipenem-cilastatin in patients with complicated urinary tract infections or acute pyelonephritis: efficacy and safety results from the phase 3 PIVOTPO study. Presentation 173. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

Author: *Sara Hockney

1. Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA

*Correspondence to sara.hockney@northwestern.edu

Disclosure: The author has declared no conflicts of interest.

Keywords: Cabotegravir (CAB), global health, HIV, HIV prevention, implementation science, lenacapavir (LEN), long-acting (LA) injectables, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]:27-31. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/JCTG4390

THIS YEAR'S IDWeek in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, highlighted a turning point in HIV prevention, as researchers and clinicians gathered to discuss advances redefining the field. The focus has shifted decisively toward long-acting, simplified, and patient-centered prevention strategies. The data presented underscored both the remarkable efficacy of new agents such as cabotegravir (CAB) and lenacapavir (LEN), and the growing emphasis on equitable implementation, real-world monitoring, and access. From twice-yearly injectables to next-generation oral and biologic approaches, the landscape of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is rapidly evolving, promising improved adherence, convenience, and meaningful narrowing of persistent prevention gaps.

CABOTEGRAVIR FOR PREEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS: FROM TRIALS TO IMPLEMENTATION

Long-acting injectable CAB (CAB-LA), administered every 2 months, continues to demonstrate robust efficacy. In the US PrEPFACTS study, only three participants (0.2%) had evidence of seroconversion over a median follow-up of 325 days, although HIV testing only occurred in about 60% of injections, highlighting ongoing gaps in monitoring.1

Safety data for CAB-LA during pregnancy are increasingly reassuring, addressing a critical knowledge gap. The open-label extension of HPTN 084 monitored cisgender

women who became pregnant while receiving CAB-LA and found pregnancy and infant outcomes comparable to population-level expectations.2,3 Maternal adverse effects, specifically gestational hypertension, were more frequent in those receiving CAB-LA, although serious complications were rare.3 Pharmacokinetic analyses demonstrated that CAB concentrations remain above protective thresholds across all trimesters, suggesting that no dose adjustments are necessary.3 While ongoing surveillance remains essential, these data provide clinicians and patients with evidence to support informed decisionmaking during pregnancy, a population historically underrepresented in clinical trials.

Carina Marquez, University of California, San Francisco, USA, reviewed the landmark PURPOSE 1 and PURPOSE 2 trials. PURPOSE 1, conducted among young women in subSaharan Africa, reported no HIV infections in the LEN arm, demonstrating 100% efficacy, although two seroconversions occurred in extended follow-up.4 PURPOSE 2, which included a broader, gender-diverse population, demonstrated a 96% reduction in HIV incidence. 4 These results led to FDA approval of LEN for PrEP in June 2025, offering the first twice-yearly injectable option and a potential solution to adherencerelated challenges.

Practical considerations for LEN include injection-site reactions and the need for an oral loading dose to achieve immediate protection. Additionally, LEN is both a substrate for and moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, creating potential drug–drug interactions. Strong inducers, such as rifampin, require dose adjustments, but

dose adjustments are not needed for oral contraceptives or gender-affirming hormone therapy.4 Encouraging data on reproductive safety were also presented. In a nested pregnancy substudy within PURPOSE 1, over 480 participants became pregnant while receiving LEN. Rates of miscarriage, stillbirth, and preterm delivery were comparable to background population rates.2,4 LEN concentrations remained consistent during pregnancy, and minimal transfer was observed through breast milk.4

While new LA agents drew considerable attention, IDWeek 2025 also highlighted the broader systems-level factors shaping HIV prevention success. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data demonstrated that, between 2012–2022, mean state-level PrEP coverage increased from 0.6% to 26.3%, accompanied by a decline in HIV diagnosis rates from 13.0 to 10.6 per 100,000 people.3 States in the highest quintile of PrEP coverage experienced

the steepest declines, confirming an inverse dose–response relationship between PrEP uptake and new infections.

Despite overall progress, wide regional and demographic disparities persist. Ofole Mgbako, NYC Health + Hospitals, New York, USA, reviewed the PrEP-to-need ratio, the number of PrEP prescriptions relative to HIV incidence, as a marker of equitable access.5 He noted substantial racial and ethnic inequalities across the USA. Josh Havens, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA, reported that only about 36% of individuals eligible for PrEP currently receive it.6 Coverage remains highest among White individuals at 94%, dropping to 24% for Hispanic/Latino persons, and only 13% for Black individuals.6

financial and insurance-related barriers impede access. A 2024 national Walgreens survey found that 19% of individuals did not fill their first PrEP prescription within 14 days, primarily due to cost and coverage considerations.9 These findings underscore that affordability and streamlined insurance authorization remain central to achieving equitable HIV prevention outcomes.

Economic barriers remain a major deterrent to PrEP initiation and further compound existing inequities in access

There is also inequitable access among women, who make up 19% of new HIV diagnoses but only 8% of PrEP users.5 Data from the STAR cohort, a longitudinal study of reproductive-age women without HIV in the Southern USA, showed that among 362 eligible women, only 9.9% had ever used PrEP.7 Barriers included cost, provider access, and inconsistent use, highlighting that clinical efficacy alone is insufficient without attention to access, equity, and patient-centered delivery.

Economic barriers remain a major deterrent to PrEP initiation and further compound existing inequities in access. Manufacturing analyses estimate that LEN could be produced for as little as 25 USD per person per year, yet USA list prices currently exceed 28,000 USD annually.⁸ Even for older oral PrEP regimens,

While equitable access and affordability remain central to PrEP uptake, data presented at IDWeek 2025 emphasized that the real-world success of LA prevention depends on effective clinical integration. Implementation studies demonstrated that embedding PrEP within existing healthcare systems, through primary care, sexual health, pharmacy, and community-based settings, reduces burden on patients and providers while improving retention.5,6 Engaging nonphysician healthcare workers, including nurses, pharmacists, and peer navigators, as well as leveraging mobile health clinics and telehealth platforms, further enhances engagement, particularly among marginalized populations.6

Real-world examples illustrate these dynamics: telehealth-based initiation of emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate PrEP at Vivent Health clinics achieved high satisfaction and 3-month followup, while the EquiPrEP study at Bellevue Hospital in New York, USA, found that over 83% of participants, including Black/ Latine cisgender men who have sex with men, Black/Latine cisgender women, and transgender/nonbinary persons, were fully adherent to LA injectable PrEP, continued on LA injectable PrEP, or switched to oral PrEP over 6 months.5,10,11 These findings highlight the value of community-based partnerships, flexible delivery models, and strategies that address structural and patient-level barriers to sustain adherence and engagement.

Monitoring strategies remain a topic of active discussion. The 2021 CDC guidelines recommend both HIV antigen/antibody and RNA testing at PrEP initiation and follow-up to minimize the risk of starting or continuing PrEP during acute infection. Updated data presented by Collen Kelley, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, using the HealthVerity database (2018–2023), challenge the incremental value of this dual approach. Following the 2021 guideline update, RNA testing among oral PrEP users increased more than sevenfold, yet positivity rates fell from 1.39% to 0.22%, and the positive predictive value dropped from 100% to 67%, translating to roughly 9,000 RNA tests required to identify one additional early infection compared with antigen/antibody testing alone.3 Reflecting these findings, International Antiviral Society-USA (IASUSA) guidelines now omit follow-up HIV RNA monitoring for CAB-LA based on HPTN 083 data, and LEN protocols similarly do not require HIV RNA monitoring.3 While CDC

guidance remains unchanged, the research suggests that routine RNA testing for asymptomatic individuals on LA PrEP may offer limited clinical benefit relative to cost and resource use.

Building on these clinical integration and monitoring strategies, emerging LA and nextgeneration PrEP modalities offer additional opportunities to expand coverage and simplify HIV prevention. Results of the Phase I clinical trial of once-yearly intramuscular LEN demonstrated higher trough levels than were seen in PURPOSE 1 and PURPOSE 2, and an additional Phase III trial is underway looking at a once-a-year lower dose with concomitant oral load.3 Ultra CAB-LA is also under investigation as an intramuscular or subcutaneous injection every 4 months.4

Beyond injectables, IDWeek 2025 also spotlighted novel modalities poised to expand PrEP’s reach. The investigational oral agent MK-8527, a next-generation nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor, showed promise as a once-monthly oral PrEP option in earlyphase trials.3,4 If validated in later studies, it may offer a valuable alternative for those who prefer pills to injections while easing adherence demands compared with daily regimens.

Researchers also presented encouraging data on broadly neutralizing antibodies as prevention tools. In a Phase I study, newborns exposed to HIV received VRC07523LS, a long-acting monoclonal antibody, in addition to standard antiretroviral prophylaxis. The intervention was safe, well tolerated, and achieved sustained serum concentrations.3 Combinations of broadly neutralizing antibodies are also under investigation as an intravenous infusion given every 6 months.

Despite advancements in LA HIV prevention, barriers continue to limit global impact. In many low- and middle-income countries, HIV prevention remains highly dependent on external funding streams, including PEPFAR and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria, leaving programs vulnerable to USA policy changes. In Malawi, abrupt reduction in USA support in early 2025 led to the suspension of community-based testing and prevention services, while treatment programs continued, demonstrating the vulnerability of prevention infrastructure and the risk of reversing epidemic control gains.5 If such cuts continue, modeling data predict a 50% increase in new HIV infections in Africa over the next 5 years, equating to 4.4–10.8 million additional new infections.5

Looking ahead, the introduction of LEN at a projected cost of 40 USD per patient per year in 120 high-incidence, resource-limited

References

1. Metzner A et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing and evidence of HIV amount real-world long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in a United States claims database: results from the PrEPFACTS study. Presentation 574. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

2. Rana A et al. Afternoon delight: challenging HIV and STI coinfection cases. Presentation 78. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

3. Kelley C. What’s hot in HIV clinical sciences. Presentation 7. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

4. Marquez C. State of the ART HIV prevention. Update in therapeutics. Presentation 118. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

countries starting in 2027 represents a potential step forward.5 PEPFAR and Global Fund are likely to prioritize LEN implantation for an estimated two million people by 2028.5 However, this focused investment may inadvertently limit patient choice, as other PrEP formulations may become less accessible in these regions.

LA HIV prevention, including CAB and LEN, is reshaping PrEP delivery by improving adherence and offering flexible options for diverse populations. Success depends not only on clinical efficacy, but also on equitable access, real-world integration, and sustainable implementation in the USA and globally. Bridging scientific innovation with structural and social considerations is essential to closing prevention gaps and reducing new infections worldwide.

5. Mgbako O. State of the ART HIV prevention. The scope and reach of HIV prevention access: the road ahead. Presentation 118. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

6. Havens J. State of the ART HIV prevention. Bridging the gap with innovation: implementation strategies for HIV prevention. Presentation 118. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

7. Carr E et al. PrEP Use among women of reproductive age enrolled in the study of treatment and reproductive outcomes. Poster P-301. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

8. Fortunak J et al. Generic lenacapavir hiv pre-exposure prophylaxis could be produced for $25 per person per year. Presentation 174. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

9. Sullivan P et al. Barriers to oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) perceived by those receiving an initial prescription: US survey analysis. Poster P-326. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

10. Firnhaber C et al. Telehealth as a modality to improve the uptake of PrEP services in Black and Latino MSM “ePrEP”. Poster P-296. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

11. Mgbako O et al. Examining preliminary adherence to long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (LAI-PrEP) among racial, sexual, and gender minority populations at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue: the EquiPrEP Study. Poster P-323. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025.

This collection of abstracts showcases developments across diverse infectious diseases, addressing real-world challenges relevant to modern clinical practice. Topics include optimizing HIV virologic suppression; sexually transmitted infection and tuberculosis screening in incarcerated populations; evaluating diagnostic tools; and stewardship interventions in pneumonia and bloodstream infections.

Authors: Hadeel Fouad,1 Melissa E. Badowski,1,2 Joy Lee,1 Jennifer Flores,1 Jane Park,3 Brian Drummond,2 Mahesh Patel,2,3 Scott Borgetti,2,3 Drew Halbur,4 *Emily N. Drwiega,1,2

1. University of Illinois Retzky College of Pharmacy, Chicago, USA

2. University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System Chicago, USA

3. University of Illinois Chicago, USA

4. Walgreens Pharmacy, Chicago, Ilinois, USA

*Correspondence to edrwiega@uic.edu

Disclosure: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, correctional medicine, HIV, reincarceration, telemedicine.

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]: 33-34. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/LCMO3544

The University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences Center (UIH), Chicago, USA, multidisciplinary telemedicine clinic provides HIV care to justice-involved individuals in the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC).1 Post-release HIV care remains challenging, with virologic suppression (VS) dropping from 73% at release to 49.7% at reincarceration into IDOC, based on previous data.2 To improve continuity of care, wrap-around services were expanded from follow-up care at UIH to medical insurance assistance, case management, employment/housing support, and statewide follow-up care.3

This Institutional Review Board (IRB)approved, retrospective cohort study occurred from January 1, 2021–August 31, 2024 and analyzed demographic, clinical,

and social determinants of health in people with HIV aged 18 years or older, who were in custody in IDOC, released, and reincarcerated during the study period. The primary outcome was a change in the number of patients with complete VS at the time of release as compared to reincarceration in those who were virologically suppressed at release.4 Secondary outcomes included change in immunologic function and identification of factors influencing loss of VS upon reincarceration.

Of 393 patients released during the study period, 95 were reincarcerated, 82 were included, and 75 had VS at the time of release. Of the 75 who achieved VS at release, 62 maintained VS (Group 1) at reincarceration, while 13 experienced loss of VS (Group 2; p=0.0001). Median cluster of differentiation (CD)4 count of those who met inclusion criteria declined significantly from release to reincarceration (p=0.0032), but the change in CD4% was not significant (p=0.0973; Table 1).

No difference was found between Group 1 and 2 in scheduling a statewide followup visit (p=0.0813), following up at UIH clinic at least once (p=1.00), or having AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) coverage (p=0.7552). Loss of VS was significantly associated with patient-reported housing instability (p=0.0046), lack of access to care (p=0.0056), living outside of Chicago (p=0.0318), and transferring from a jail in a rural setting (p=0.0054).

CD4 count (cells/mm3; IQR)

Number of patients with CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (%) 4/82 (4.9%) 4/82 (4.9%)

*Patients who were not suppressed at release: four patients were released before the lab results could be updated, two patients preferred no pharmacotherapy, and one patient was not started on medication because the team decided it would be more effective to initiate treatment after release to ensure better follow-up and continuity of care.

CD: cluster of differentiation; IQR: interquartile range; NS: not significant; VL: viral load.

As the role of the IDOC telemedicine team expanded, the proportion of individuals who maintained VS upon reincarceration increased from 49.7% in 2014 to 82.7% in 2024. While interventions show progress, more targeted efforts are needed to address housing, care access, and non-Chicago residency.

1. Fouad H et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) virologic suppression among reincarcerated individuals within in the illinois department of corrections. Poster. IDWeek, October 19–22, 2025.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV Diagnoses, deaths, and prevalence: 2025 update. 2025. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv-data/ nhss/hiv-diagnoses-deaths-and-prevalence-2025. html. Last accessed: 19 August 2025.

3. Widra E. New data on HIV in prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic underscore links between HIV and incarceration. 2023. Available at: https://www. prisonpolicy.org/blog/2023/06/01/hiv_in_prisons/. Last accessed: 19 August 2025.

4. Badowski ME, Patel M. Evaluation of immunologic and virologic function in reincarcerated patients living with HIV or AIDS. J Correct Health Care. 2022;28(3):203-6.

Authors: *Sara Hockney,1 Dana Mueller,2 Alex Phillbrick,1 Jenna Berlet,1 Shannon Galvin1

1. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, USA

2. Southwest Infectious Disease & Internal Medicine, Palos Heights, Illinois, USA *Correspondence to sara.hockney@northwestern.edu

Disclosure: Galvin has received research funding from GSK, unrelated to the current article. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Keywords: Anti-retroviral therapy (ART), cabotegravir-rilpivirine (CAB/RPV), HIV, longacting (LA) injectables.

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]:3536. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/ WNZA9304

Long-acting (LA) injectable cabotegravirrilpivirine (CAB/RPV) is a novel antiretroviral therapy (ART) option for virologically suppressed persons with HIV (PWH) who have no prior treatment failure and no known or suspected resistance to either agent.1 However, in practice, patients often initiate LA CAB/RPV with incomplete or unknown treatment and resistance histories. This study aimed to characterize reasons for LA CAB/RPV therapy discontinuation in clinical practice and to describe a subset of cases in which virologic failure occurred.

The authors retrospectively reviewed all patients seen in an infectious diseases clinic between January 1, 2022–April 17, 2025 who were on LA CAB/RPV for HIV treatment.2 Virologic failure was defined as two or more consecutive viral load measurements ≥200 copies/mL. Statistics were performed in R version 4.4.2.

During the study period, 201 PWH were treated with LA CAB/RPV for an average of 472 days (range: 0–1,241). Those on LA CAB/RPV were predominantly male (85.6%) with a mean age of 47 years. Therapy was discontinued in 41 (20%) patients. Reasons for discontinuation included transfer of care (n=11; 27%), insurance (n=8; 20%), adherence (n=7; 17%), patient preference (n=7; 17%), virologic failure (n=4; 10%), intolerance (n=3; 7%), and death (n=1; 2%). Combined genotype/phenotype testing was done at the time of failure in the four patients who discontinued therapy due to virologic failure (Table 1). Two had RPV resistance, one had integrase resistance, and one had both RPV resistance and intermediate CAB resistance. One additional patient experienced transient virologic failure with a maximum viral load of 1,230 copies/mL. Resistance testing was negative, and virological suppression was subsequently achieved with no change in therapy. There was no difference in BMI between patients who experienced virologic failure and those who did not (32.06 kg/m2 versus 28.92 kg/m2; p=0.11).

Table 1: Clinical characteristics, resistance profiles, and outcomes of patients with virologic failure on long-acting injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine.

42, M Genotype negative for relevant mutations (4 years prior)

60, M None on file

43, M Phenotype with resistance to DTG, EVG, RAL (1 year prior)

47, M

None on file

Viral blips for 20 m, then ↑ to 2,350 at 21 m K101P

First VL at 5 m 192, then ↑ to 13,100 at 9 m

First VL at 3 m 17,700

High-level RPV resistance

Y181C Intermediate RPV resistance

Not assessed

First VL at 6 m 386,000 E138A M230L

61, M None on file VL <20 for 4 m then ↑ to 1,230 at 5 m

None

Resistance to DTG, EVG, RAL, BIC

High-level RPV resistance; partial sensitivity to CAB

Sensitive to RPV, DTG, EVG, RAL, BIC

2. Hockney S et al. Discontinuation patterns and virologic failure among persons with HIV receiving long-acting injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine antiretroviral therapy. Poster P-384. IDWeek, October 19-22, 2025. Patient (age, sex)

Resumed prior regimen of FTC/TAF, DTG + DOR, and resuppressed

Resumed prior regimen of ATV/r + ABC/3TC, and resuppressed

Resumed prior regimen of DRV/ COBI/FTC/TAF, and re-suppressed

Resumed prior regimen of DRV/ COBI/FTC/TAF, and re-suppressed

Continued LA CAB/RPV, and resuppressed by 7 m

ABC/3TC: abacavir/lamivudine; ATV/r: atazanavir/ritonavir; BIC: bictegravir; CAB: cabotegravir; DOR: doravirine; DRV/COBI: darunavir/cobicistat; DTG: dolutegravir; EVG: elvitegravir; FTC/TAF: emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; LA: long-acting; m: months; M: male; RAL: raltegravir; RPV: rilpivirine; VL: viral load.

In PWH on LA CAB/RPV, discontinuation occurred primarily due to transfer of care and insurance barriers. Virologic failure was rare and was associated with underlying resistance but not BMI. These findings highlight the tolerability of LA CAB/RPV in clinical practice and the need to address access issues to optimize patient outcomes.2

References

1. FDA. Cabenuva. 2021. Available at: https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/ label/2021/212888s000lbl.pdf. Last accessed: 27 October 2025.

Authors: Danny Schreiber,¹ Emily N. Drwiega,¹ Miguel Perez,1 Rita Uda,1 Mahesh Patel,2 Scott Borgetti,2 *Melissa Badowski¹

1. Department of Pharmacy Practice, Retzky College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois Chicago, USA

2. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Illinois Chicago, USA

*Correspondence to badowski@uic.edu

Disclosure: Borgetti has received grants or contracts from GSK for an RSV vaccine study. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Keywords: Chlamydia, co-infection, corrections, gonorrhea, HIV/AIDS, retrovirus, sexually transmitted infection (STI), syphilis.

Citation: Microbiol Infect Dis AMJ. 2025;3[1]:3738. https://doi.org/10.33590/microbiolinfectdisam/ RRVF1763

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) have a disproportionately high prevalence in individuals in custody and persons with HIV (PWH). However, limited data exist for the rates of infection in individuals who are in custody, particularly PWH, leading to a potential gap in timely and appropriate recognition and treatment of STIs. In the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC), persons in custody are screened at initial intake and those with HIV are seen by a multidisciplinary care team via telemedicine to manage HIV care and related STIs.1,2

Electronic medical records of PWH receiving care via IDOC telemedicine in conjunction with the University of Illinois Hospital and

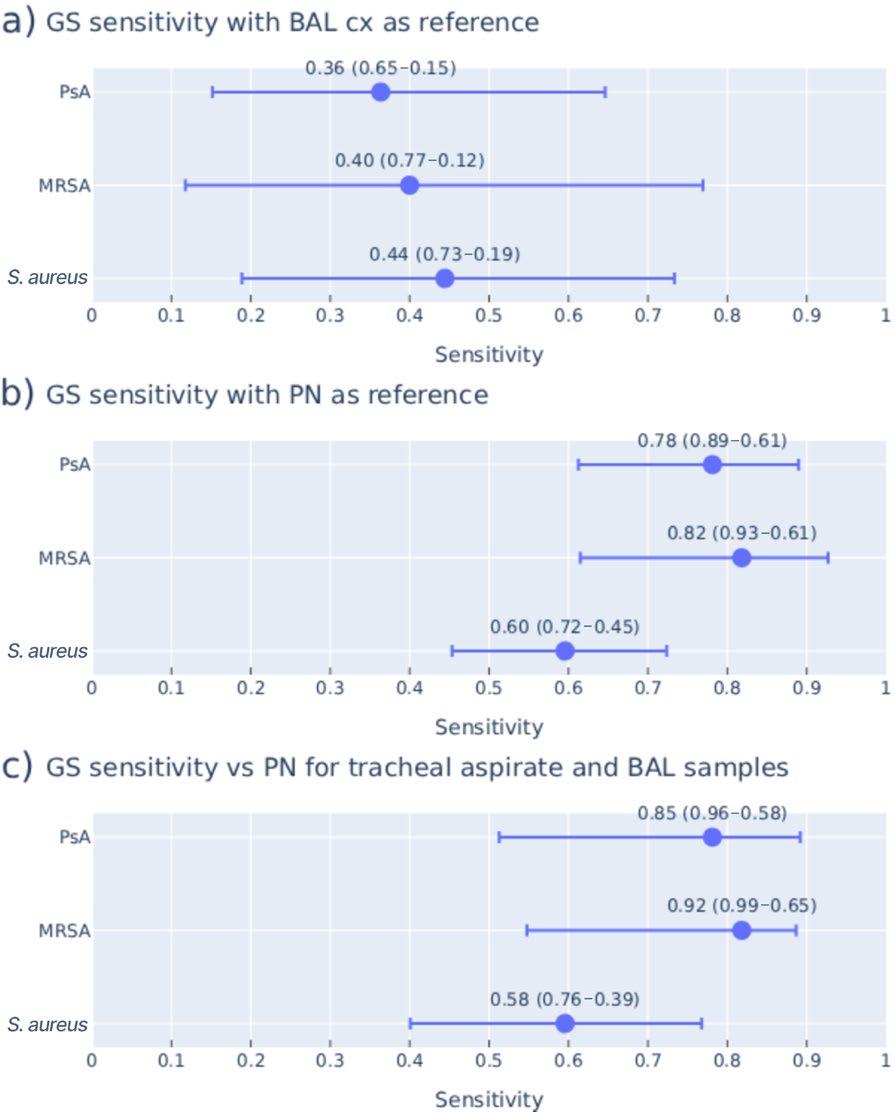

Health Sciences System, Chicago, USA, were reviewed from January 1st, 2021–June 30th, 2024. The primary objective was to determine the frequency of screening and positivity for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis. HIV viral load and other known STI risk factors were also collected to assess predictors of STI positivity.