8 minute read

Nutrition: Regional challenges

A horse’s eye lacks depth of perception, which is why Johnny jumped over tyre tracks in the sand until he realised he could walk on them (Image by Candida Baker).

differences in tone and intensity. So, for example, if we are making a choice between a juicy red or green apple, a horse will see both apples as simply a deeper shade of brown/yellow.

There’s another reason for this adaptation as well, which is that horses need to be able to see during the night and the day, so the coloursensitive cones of the eye need to be less triggered to react to changes in light – and having a more rudimentary colour vision allows the horse to watch for predators, and to move 24/7. At the same time having colour vision, as opposed to black and white helps horses see predators that might otherwise be camouflaged from them.

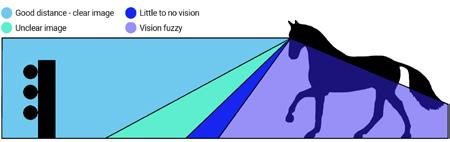

Another difference in the way horses see is that they don’t focus on things the way we do – and it explains why horses are often so mystified by what they think is the sudden appearance of a new or a strange object. We, for instance, have a large range of what is called ‘accommodation’, meaning that the muscles that squeeze the lens and change its shape provide us with the ability to focus when we are looking at something close to us, and then change the focus to drive, or look at something further away. Humans and animals that use their hands or front paws to hold, move or manipulate objects all have a high range of accommodation at around 10 diopters - horses and dogs have a range of around two diopters. What a horse’s eye is designed to do is to bring a distant object (that could be a predator) sharply into focus on the retina, not to focus on close-up objects. Horses have virtually no ‘accommodation’, so their focus changes only minimally. Interestingly horses also have little to no depth perception.

I once personally experienced the depth perception question when I took our Arabian Galloway to the beach for the first time. His favourite sport was jumping, and as we were walking up the beach, every time we came to the tracks of car tyres in the sand, he was jumping them – with great leaps! I couldn’t work out why, but the friend I was with explained to me that to Johnny, the tracks looked solid and he thought he had to jump them to get over them. So we walked carefully in between the ‘jumps’, and gradually introduced him to the idea that he could, in fact, walk on them.

When you think about their lack of depth perception, lack of focus, and limited colour range it makes the idea of them jumping even more extraordinary. A cross country jump, for example, that will appear in bright colour and sharp relief to the rider will be a blurry mass to the horse. At three metres away, the jump loses focus, and by the two-metre mark, the horse cannot judge the distance to the jump, or even see it accurately.

Add into the mix what horses do for us in all the sports we use them for, everything from cutting and reining, to polo and racing, and more, and their trust us in us becomes even more amazing. Even something as simple as opening a gate doesn’t look the same to us as it does to the horse, in fact when they’re close up to the gate they can hardly see it, relying entirely on our aids to guide them through.

So next time you ‘ask’ your horse to do something new – think about how your horse is ‘seeing’ it. Give them credit for the extraordinary leaps of faith they take for us, just because we ask, because sometimes they are literally flying blind.

Some of the information in this article came from The Nature of Horses: Their

Evolution, Intelligence and Behaviour

by Stephen Budiansky, published in 1997 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Candida Baker runs a Facebook page, The Horse Listener, and is president of an equine rescue and rehabilitation charity, Equus Alliance.

Widgee Total Eclipse

BREED: Purebred Trakehner Stallion SIRE/DAM: By Korrit (Imp) out of Tally ho Midori)

COLOUR: Black

HEIGHT: 16.1h

REGISTERED: ACE and Arabian Warmblood registration

TRAINING: Trained primary by his AOR from breaking to date DISCIPLINE: Advanced Dressage LOCATION: Located at Exeter NSW

TRAITS: Stamps progeny with gorgeous bling and super trainable attitudes and lovely movement.

NATURE: Beautiful nature in hand and under saddle ridden and competed by young rider and para dressage rider. RATE: $1100 with LFG. Chilled semen.

NUTRITION

Regional challenges in feeding

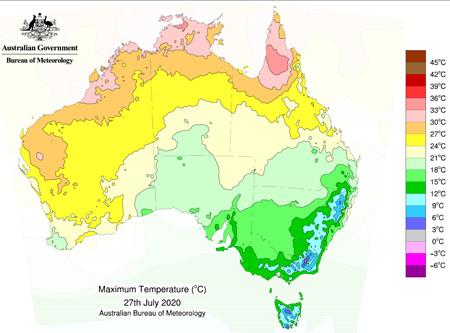

With regions ranging from cool temperate, and temperate to arid, subtropical and tropical, the Australian climate poses some interesting feeding challenges, writes LARISSA BILSTON.

Australian horse owners face very different management challenges depending on the climatic zone they live in. The impact of climate on pastures, feed quality and availability across different regions has a significant influence on what you need to feed your horse to optimise health and nutrition.

High oxalate pastures – tropical climates and coastal areas

Graziers introduced many species of high-producing C4 grasses from Africa into tropical Australia in the last century. Many of these grasses were very successful in Australian climates and have now become naturalised throughout tropical and sub-tropical zones. Some C4 species also grow alongside naturalised C3 grasses in temperate zones.

Most of the introduced C4 pasture grasses contain high levels of oxalates, which are a naturally occurring biomineral that help plants to regulate calcium levels and photosynthesize efficiently. Many plants contain oxalates but only some contain the very high levels that can cause problems for horses. that most commonly occur in horse paddocks in the northern half of Australia are Buffel, Setaria, Green Panic, Humidicola, Para, Signal and Pangola grasses. Kikuyu is another high oxalate species which grows well in coastal areas from northern Australia right down the eastern coast and into north-eastern Tasmania.

The problem with these grasses in horse pastures is that the oxalate molecule binds calcium, making it unavailable to the horse. Interestingly, oxalates do not cause problems for sheep and cattle because their rumen (the first stomach of a ruminant) can metabolize oxalates into harmless products very early in the digestive tract.

If not supplemented with adequate calcium, horses grazing high oxalate pastures become calcium deficient and draw on the calcium reserves in their bones to maintain critical blood calcium levels. This condition is called Big Head or Bran Disease, more accurately known as nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism (NSH) which is effectively osteoporosis in horses.

Horses grazing high oxalate pastures need to be supplemented with extra calcium to ensure there is enough available calcium in their diet to meet their requirements. Both inorganic and organic (chelated) forms of calcium are effective provided that they are supplemented in adequate amounts. Since there are many variables to be considered in calculating supplementation needs, advice from a qualified nutritionist experienced in tropical equine nutrition is recommended.

Sweet grasses and laminitis prone/insulin resistant horses

Many of the high producing C3 grasses introduced last century from Europe, the UK and USA for temperate sheep and cattle production have succeeded so well in the Australian climate that they are now naturalised species. These grass species have been bred to produce rapid growth of the high energy (calorie), high protein feed needed for milk and meat production.

The carbohydrate (sugar and starch) levels of ryegrass and some other introduced grasses, particularly the C3 species, are too high for horses who evolved to graze lower quality roughages. Horses rapidly gain weight on high carbohydrate pastures which puts them at risk of equine metabolic disease, insulin resistance and laminitis. Sudden changes in grass quality and availability especially during spring and autumn can disrupt the equine gut microbiome which causes diarrhea and may lead to colic and laminitis.

When planting horse friendly pastures in temperate zones choose a mix of slower growing, higher fibre, lower nutrient varieties such as Cocksfoot, Browntop Bentgrass, Yorkshire Fog, Crested Dogtail Grass Prairie, and Australian native grasses – Wallaby, Native Wheatgrass, Native Bluegrass and Weeping Grass are amongst the best suited to grazing.

Species for horse friendly pastures in tropical areas include Rhodes Grass (this is a high producing, low oxalate C4 grass) and native grasses such as Bluegrass, Native Wheatgrass, Mitchell, Kangaroo and Wallaby Grass.

Horses prone to laminitis will need very careful management especially during spring and autumn. Restricted intake via use of grazing muzzles and removal from grass with or without limited turnout time are necessary management tools. Replace fresh grass with low calorie hay (which may be soaked to remove calories), and minimise hard feeds to just enough to provide essential vitamins, minerals and the prebiotics designed to improve insulin sensitivity. Consider the use of hindgut buffers and probiotic live yeast to help maintain a more stable hind gut pH.

Too much of a good thing. Horses prone to laminitis need careful management especially during spring and autumn.

Lack of pasture

Most parts of Australia experience seasons where grass availability is inadequate to meet horse requirements. Grass growth can be limited by cold weather, short days, dry conditions and over-grazing.

Whenever pasture levels are low or grasses are dry and stalky, horses need to be fed hay. Horses need a minimum of one per cent of their body weight as dietary forage. For the majority of horses, the required amount of hay is closer to two per cent of their body weight (i.e. a 500 kg horse needs 10 to 12kg of hay per day when grass is not available, and a 250kg pony needs 5 to 6 kg).

The hay used to replace pasture intake should be a grass or meadow hay. Lucerne should not exceed more than 20 to 30 per cent of forage intake.

Horses reliant on hay or dry pasture for more than half of their forage intake should also be given