3 minute read

The Horse Listener

AROUND THE TRAPS

ABOVE: Fiona Weal and Amaranda Jazzmine won Best Junior at the APSB Pony National show held at SIEC in November 2019 (Image by Foxwood Photography). TOP: Molly Palmer and Blondie sharing the love during COVID lockdown in Macclesfield, Victoria (Image by Jodie Palmer). Water jump? No problem! Madison Hubbard and Do the Twist competing at Silver Hills (Image by Danielle Hubbard). TOP: Keira Hawkey and her Warmblood gelding Hamon Park Wenergy enjoying the surf and sand at Queensland’s Beachmere Beach (Image by Brett Hawkey).

THE HORSE LISTENER

How Horses See

Did you know that a horse really can’t distinguish between a green apple and a red apple, or that they can’t see a jump during and after take-off? CANDIDA BAKER examines the complex world of the horse’s eye.

Aquestion for all you horse lovers out there. Which land mammal has the largest eyes?

If you guessed the horse, you’re correct. But large eyes don’t necessarily mean great sight, and the eye of the horse has developed to see in a very different way to the humans who ride them, or care for them.

For example – and to me this is a truly amazing idea – when a horse is jumping, as it takes off over the jump, it can’t actually see it. It has to rely on its visual memory of the jump a stride or two out. And of course, on its trust in the rider on its back. If you think about that just for a second, it makes it even more amazing what horses will do when we ask them!

Sight is arguably our most direct link to the environment around us – for humans, horses and other mammals. A horse’s eyes are huge, and set on the side of the head to enable their almost 360 degree ability to see, taking in almost the entire horizon.

So why have their eyes developed in the way they have? Well, of course, since horses were originally a large prey animal, they needed an advantage over predators, and one of those advantages is the ability to see to almost behind them.

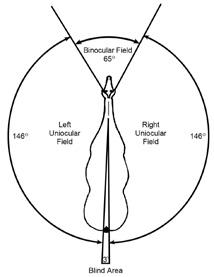

It’s generally believed that horses have one blind spot, just on each side of their rump and right behind them, but in fact they have two – there is another one directly in front of their nose. Horses, it seems, have to move their heads up and down to see objects in sharp detail, which may explain why a horse will suddenly shy at something that has been there for a while, because it literally hasn’t registered.

Their field of vision is divided into a binocular field of 65 degrees directly in front and slightly to the side of their eyes, the rest, on each side is 146 degrees of unicocular field, giving them a much broader range than we have but with less focus, to put it simply.

And what about colour? Surely horses can see that beautiful green grass in front of them? I know, growing up with ponies in the countryside in England, that I would often fondly imagine as I saw my pony grazing in the green field, or fed her a juicy green apple from the orchard, or the treat of a stolen orange carrot from my mother’s vegetable garden, that she ‘saw’ those things in as rich a way as I did. When I started jumping over coloured poles, it didn’t even occur to me that she, and later all the other horses I rode, saw them differently, but in fact horses have limited colour vision.

Unlike birds or insects or human omnivores that feast on fruits and flowers and berries, horses have far less need to see in colour. They have what is called dichromatic vision, seeing two of the three wavelengths of visible light as opposed to our trichromatic vision, in which we see all three. It’s been proved that horses, therefore, see colour in the same manner as a human who is colour-blind, but on a red-blue rather than on a red-green spectrum. A horse really can’t tell green from grey, or gauge to any significant degree