Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Start reading on any device today!

(Ebook) Biota Grow 2C gather 2C cook by Loucas, Jason; Viles, James ISBN 9781459699816, 9781743365571, 9781925268492, 1459699815, 1743365578, 1925268497

https://ebooknice.com/product/biota-grow-2c-gather-2c-cook-6661374

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) Matematik 5000+ Kurs 2c Lärobok by Lena Alfredsson, Hans Heikne, Sanna Bodemyr ISBN 9789127456600, 9127456609

https://ebooknice.com/product/matematik-5000-kurs-2c-larobok-23848312

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) SAT II Success MATH 1C and 2C 2002 (Peterson's SAT II Success) by Peterson's ISBN 9780768906677, 0768906679

https://ebooknice.com/product/sat-ii-success-math-1c-and-2c-2002-peterson-s-satii-success-1722018

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) James A. Michener’s Writer’s Handbook: Explorations in Writing and Publishing by James A. Michener ISBN 9780679741268, 0679741267

https://ebooknice.com/product/james-a-micheners-writers-handbook-explorationsin-writing-and-publishing-5219116

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) Master SAT II Math 1c and 2c 4th ed (Arco Master the SAT Subject Test: Math Levels 1 & 2) by Arco ISBN 9780768923049, 0768923042

https://ebooknice.com/product/master-sat-ii-math-1c-and-2c-4th-ed-arco-masterthe-sat-subject-test-math-levels-1-2-2326094

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) Cambridge IGCSE and O Level History Workbook 2C - Depth Study: the United States, 1919-41 2nd Edition by Benjamin Harrison ISBN 9781398375147, 9781398375048, 1398375144, 1398375047

https://ebooknice.com/product/cambridge-igcse-and-o-level-historyworkbook-2c-depth-study-the-united-states-1919-41-2nd-edition-53538044

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) The Judas Strain: A Novel by James Rollins ISBN 9780060763893, 9780061460425, 0060763892, 0061460427

https://ebooknice.com/product/the-judas-strain-a-novel-1732460

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) The Golden Spoon: a Novel: A Novel by Jessa Maxwell

https://ebooknice.com/product/the-golden-spoon-a-novel-a-novel-48370530

ebooknice.com

(Ebook) Friedrichsburg: A Novel by Friedrich Armand Strubberg; James C. Kearney ISBN 9780292737709

https://ebooknice.com/product/friedrichsburg-a-novel-51978330

ebooknice.com

The Drifters is a work of historical �ction.

Apart from the well-known actual people, events, and locales that �gure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used �ctitiously.

Any resemblance to current events or locales, or to living persons, is entirely coincidental.

2014 Dial Press Trade Paperback Edition

Copyright © 1971 by James Michener

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Dial Press Trade Paperbacks, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

DIAL PRESS and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, in 1971.

An extract from The Lusiads of Luis de Camoes, translated by Leonard Bacon, is reprinted by permission of The Hispanic Society of America, New York, 1966.

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-5149-8

www.dialpress.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

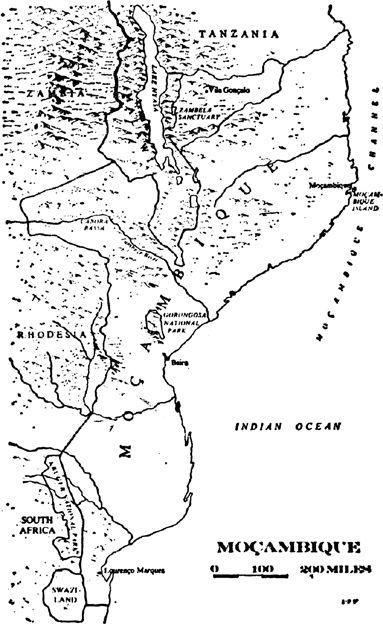

Copyright Maps

I Joe

II Britta

III Monica

IV Cato

V Yigal

VI Gretchen

VII Torremolinos

VIII Algarve

IX The Tech Rep

X Pamplona

XI Moçambique

XII Marrakech

Other Books by This Author About the Author

Youth is truth.

No man is so foolish as to desire war more than peace: for in peace sons bury their fathers, but in war fathers bury their sons.— Herodotus

The greatest coup engineered by the university in recent years had been the employment of Dr. Richard Conover, Nobel Prize winner in biology. He added much luster to the faculty, but his principal work continued to focus in Washington, where he was conducting experiments on nerve gases for the Department of Defense. This meant that he was unable to do any actual teaching at the university; his courses were handled by a series of attractive young men who were, on the average, two and one half years older than the university students, four per cent more intelligent, and six per cent better adjusted. Of course, students could sometimes catch a glimpse of Dr. Conover heading for the airport on Sunday afternoon, and this reassured them.

War is good business. Invest your sons.

The university had lost its way and everyone knew it except the Board of Regents, the alumni, the faculty and ninety per cent of the students.

I am a serious student. Please do not spindle, fold or staple me.

Never pick up a girl before one o’clock in the afternoon. If she’s so beautiful, what’s she doing out of bed before noon?

If a young man, no matter how insecure, can’t make it with the girls in Torremolinos, he had better resign from the human race.

Zeus picked up Ganymede at the Wilted Swan.

was no brain-train like Berkeley nor a mod-squad like Stanford; it was one of the numerous solid institutions that dotted California and accounted for that state’s superiority in so many �elds; where a state like Pennsylvania provided a college education for thirty-one percent of its high school graduates, California educated seventythree, and this di�erence had to tell. Joe held his own with the competition, drawing down grades that kept him in college and out of the draft.

It was this latter that engendered his moral crisis. Four ugly events accumulated in a short period of time. They haunted him, could not be dismissed; of itself, each was trivial, a thing young men would have been able to dismiss ten years ago. Now, in the autumn of 1968, they coalesced to form a dreadful incubus.

The �rst event was accidental. His roommate, who got almost straight As and had done so throughout high school, was visited one day by an older boy named Karl, who had graduated the previous year. He was a big, able fellow who dropped by the room and lounged on the bed with a beer can. ‘No matter what they tell you,’ he ponti�cated, ‘take three education courses. The wise guys laughed when I dropped out of pre-law and took Elementary Ed … Diaper Changing III, they called it. All right, they’re in Vietnam. I’m salted away in an elementary school in Anaheim. I’m safe from the draft for the duration.’ He lolled back against the pillows, swigged his beer, and repeated his admonition, ‘Take education.’

‘How do you �nd teaching?’ Joe asked.

‘Who gives a goddamn? You report in the morning. The kids are raising hell. You keep them from tearing the place apart. You go home at night.’

‘What do you teach them?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Won’t you get �red?’

‘I’m big. The kids are afraid of me. So I keep reasonable order. The principal is so grateful for one quiet room he don’t give a damn if I teach ’em anything or not.’

‘Sounds pretty awful,’ Joe said.

The football player looked at Joe, started to hand him a wisecrack, reconsidered, and said, ‘If the girl you got pregnant happened to be someone you loved, you’d be ahead of the game.’

‘Yours wasn’t?’ Joe asked quietly.

‘Mine wasn’t,’ the big man said.

The third experience made a moral confrontation unavoidable. On the �oor above was a pitiful jerk named Max who studied every weekend, with never a chance of understanding calculus or Adam Smith. He was a fat boy from Los Angeles with a bad complexion and he wanted to be a doctor, as his mother said, but his professors quickly saw that this was out of the question, so he had shifted to business, but this was also impossible.

‘You’ve got to stay in college!’ his parents bellowed. ‘You want to disgrace us? You want to fail and go into the army?’

His mother had arranged for him to transfer to education. ‘So you can get a job teaching in Los Angeles, like Harry Phillips, and you’re safe.’ He had switched to education but lacked even the intelligence to pass those courses, and now it appeared that he was to be dismissed from the university, lose his draft deferment, and return to 1-A.

At this crisis Max waddled through the dormitory, looking for someone who would be willing to slip into the examination room and write a critical test for him. ‘The questions are easy,’ he explained, ‘but I just can’t organize my thoughts.’ When he found no one on the second �oor willing to take the risk, he came back to Joe and said, ‘Even if you haven’t taken the course, Joe, you could answer the questions. I know you could.’ It was a pitiful performance, and after the exams were corrected, Max got the bad news. He was out. His deferment was ended. He must go into the army.

His distracted parents came to collect him, and in the privacy of his room, gave him hell, so that he left the dormitory red-eyed and trembling. He broke away from his parents to say goodbye to Joe. ‘You were a good friend,’ he said. Then, shuddering, he walked toward the car.

Whitey. See you in Vietnam,’ and another said, ‘Not him. He’s college.’ Joe laughed, cocked his right thumb and fore�nger like a pistol and shot at the soldier, clicking his tongue as he did. The soldier fell back two paces, clutched his heart, and said, ‘Damn, he shoot straight.’

That was all. Joe passed on, but the meaningless incident kept reverberating in his mind, day after day—the horrible fact that in this war black men who could not a�ord to attend university were drafted and white men who had the money were not. It was indecent, immoral, infuriating, and everything said by the leaders of society, men like General Hershey and J. Edgar Hoover, simply exacerbated the basic wrong. Negroes were drafted, white men weren’t; the poor were hauled o� to war, the rich weren’t; the stupid were shot at, the bright boys weren’t. And it was all done from an immoral premise in prosecution of a war immorally founded.

Perplexed by these confusions, Joe entered the �nal month of the year, unaware that his roommate, thanks to his training in philosophy, had arrived at certain important conclusions that Joe would not reach for some weeks to come. Shortly before Christmas a group of students opposed to the war announced a peace rally. It was scheduled for two in the afternoon at the main quadrangle, and by one the campus was crowded with spectators from the town. Special campus police were on hand, with instructions to prevent physical violence. They were supported by regular police, also determined to forestall trouble. When these saw a parade approaching with signs like Love America or Leave It, U.S.A. All the Way, and Back Our Brave Men in Vietnam, they quietly diverted the marchers from the campus.

Through a bull horn, one of the policemen told these counterdemonstrators, ‘The peaceniks have a constitutional right to their say. You can’t take those signs on campus.’ The signs were con�scated but the marchers were allowed to disperse through the crowd in the quadrangle.

When Joe’s roommate looked down from their dormitory and saw the strangers and the two groups of police, he said, ‘Things may get

tough. I want you to know that what I’m going to do this afternoon isn’t done hastily. I’ve been thinking about it ever since that day we saw Karl teaching in his school.’

He and Joe walked down to the quadrangle, where they parted, because Joe always backed away from public demonstrations. As a freshman he had refused to attend football rallies and he felt the same about campus protests. ‘You do your thing,’ he told his roommate. ‘I’ll watch from over here.’

The demonstration proceeded peacefully. Joe, perched on the base of a statue commemorating the founder of the university, listened to the loudspeakers as a wispy little professor of chemistry, Dr. Laurence Rubin, tried to explain that the war was damaging America’s posture at home and abroad, but hecklers from the parade kept shouting, ‘You wanna surrender?’ Rubin had anticipated such a charge, but when he tried to explain the di�erence between surrender and planned withdrawal from a non-productive situation, the hecklers would not allow him to give it, shouting, ‘Ending the war is Nixon’s job. Shut up and let him do it.’ So Professor Rubin was driven from the microphone with his basic thesis unstated.

A student with a voice capable of �lling the quadrangle grabbed the microphone and shouted, ‘If action is the only thing Washington can understand, we’ll give them action.’ Joe noticed that as soon as this echoed through the loudspeakers, both the campus police and the regulars moved closer to the platform. The speaker saw them coming but nevertheless gave a signal, whereupon a group of some thirty or forty coeds began singing ‘Blowin’ in the Wind,’ a stately chant of resistance which some of the men in the audience took up. It was a wintry song, well adapted to this quadrangle with its milling and unde�ned groups.

When the song was at its height a group of seven young men climbed onto the platform, and in view of everyone, lit cigarette lighters and with studied resolve burned their draft cards. To his surprise, Joe saw that his quiet roommate was among them, was indeed their leader in this act of de�ance that solemnly separated them from a society they could no longer respect and whose laws they would no longer obey.

The sight of smoke curling into the air in�amed the marchers from the town, and even those spectators who had brought with them no intention of violence found themselves outraged. Suddenly, from many quarters, people started rushing at the platform, trying to pull down the seven card-burners, and this brought the two groups of police into action, their clubs swinging. To Joe’s astonishment, the police did not use their clubs against the rioters; instead they reached up, grabbed the protesting students, and beat them as they dragged them to the ground. Joe’s roommate broke loose and started to run away, but another group of students, infuriated by the card-burning, blocked his way and began punching him in the face. He lurched backward into a girl, who screamed. Other girls, not yet involved but afraid that they might be knocked down, began screaming, and a general melee developed.

Now the police took over, slam-banging their way through the crowd to arrest the card-burners. Joe’s roommate, his head befuddled by the punches he had taken, stumbled toward the police as if he were attacking them and was greeted by a rain of sickening blows which knocked him to the pavement. Joe, when he saw him fall, automatically leaped from the safety of his pedestal and ran to help, but the police considered him one more longhaired troublemaker and waded into him.

One club racked him up, another smashed into his gut, and a third cracked across his skull and brought him down in a heap. He said later that he heard this last blow before he felt its piercing message; it was the last thing he did hear, for he collapsed in a lump of meaningless bone and unassociated �esh. He vaguely remembered thinking that his knees had disappeared and his legs had become water. Then he fainted.

While his roommate sat in jail awaiting trial, Joe stayed alone in the dormitory grappling with a slowly developing conviction. Customarily such painful assessment comes to a man in his late forties, when he girds himself for a �nal push, or in his �fties, when he assesses the dark failure in which he is embroiled without chance

of escape, but for Joe’s generation the time of reappraisal came early, and he faced his alone.

He liked girls and dated several, but so far had found none with whom he would be easy in discussing his present crisis. He was also familiar with certain boys in the dorm, but knew none well enough to burden them with his confusion. There were no professors with whom he would have cared to talk; those who showed understanding were too busy with their own work, and those who were available were clods with whom any meaningful dialogue would be impossible. So he stayed to himself.

The university was on the quarter system, which required a battery of exams prior to Christmas. Joe mustered enough concentration to try Professor Rubin’s chemistry exam, but he did so poorly that when history and English III came around, he didn’t bother to report to the examination hall. He stayed in his room and tried to face up to the various dilemmas in which he found himself. He did not shave, nor did he report to the dining hall. Late at night he would wander through the dark streets and pick up a hamburger and some co�ee, but for the most part he kept to himself, rubbing the knobby bruise on his head and thinking.

A girl from La Jolla dropped o� a letter inviting him to drive her home in her car. When he read the message he could visualize her, an attractive kid with neatly combed hair pulled back into a ponytail. It would be fun spending the Christmas vacation with her, but not this year. He went down to the phone. ‘That you, Elinor? It was a sweet letter you sent. I’d like to, but I’m all chopped up.’ She said, ‘I know,’ and drove home alone.

For the �rst week Joe stayed in his silent room within the silent dormitory. Since the dining room was closed, he ate pick-up meals, and had his dinner at a hamburger joint. As the year drew to a close he tried to cast up his situation, and concluded that for him the university was washed up. He could not in honesty remain in what had become for many a draft haven. He rejected refuge in these classrooms when men like Max had to leave for war, or when the Negroes down the back alleys were being conscripted. He refused to compromise any longer with an immoral position.

quadrangle the other day they actually hated … they could have killed my roommate … because he wanted peace.’

Alone in his room, he remembered a lecture given by one of the young professors: ‘The United States is the most militaristic country on earth. Newspapers, television, universities and even the churches are dedicated to warfare and any voice that speaks out against it has to be silenced. You will notice that newspapers refer to anti-war spokesmen as “the so-called peaceniks.” Cartoonists depict them as lunatics. Television commentators speak of them as rioters and scum who should be driven from the streets. Our nation feels it has to destroy the peace people because it knows that to keep our country functioning, we must have war. Not for economic reasons, for spiritual ones.’

Joe recalled a conversation he once had with a music major: ‘This university has a very good conservatory. Our teachers can put on damned good opera. But do you know how the board of regents judges the department? How good the marching band is? If a hundred and �fty young men and women in military uniform swing onto the football �eld between halves, and keep step, then the music department gets a generous budget next year … and to hell with Beethoven. The regents are right. Do you know why? Because every little town in California demands that its high school have a marching band … in military uniform … keeping step … drilling to John Philip Sousa. The citizens want this because they love the military … they love parades. And if this university can’t provide music graduates to build marching bands—by God, the small towns will look to some other university … and we’ll be in trouble. The regents aren’t dumb. They know what’s important.’

Joe had been so fascinated by this theory of martial music that he had accompanied his friend on an excursion to a small town to watch the marching band which had been trained by a recent graduate from the music department, and things were the way he had described, except that in addition to the band, they had a drill team consisting of little girls thirteen and fourteen dressed in military uniforms and carrying wooden replicas of army ri�es, complete with leather slings. Led by an ex-army man in his �fties,

the girls went through drills as if they were an infantry company on its way to the Civil War, and when at the end they lined up in one single rank and �red an imitation salute, a cannon went o� and everyone cheered.

Wherever Joe looked in his society he found new proof of America’s fascination with violence. If he went into town he passed a dismal hall whose weather-beaten clapboard sides carried the sign: Learn Karate! Destroy Your Assailant! A crudely drawn picture showed a fearless young man breaking the neck of a colored man who leaped at him from behind a corner. Some years ago the hall had carried a simpler sign: Learn Judo. Protect Yourself. But this had attracted few customers, for it was self-defense. With karate you could kill the other man, and this possibility was so enticing that enrollments quadrupled.

On television it was professional football with its planned mayhem that attracted spectators who used to watch baseball, and in the movies it was constant violence, showing dozens dead where one would have made the point. But most of all there was Vietnam, that running sore which contaminated so much. ‘We want peace in Vietnam,’ Joe re�ected as he looked at the letter which had so aroused him, ‘but God help Richard Nixon if he tries to do anything about it when he becomes President.’ He threw the letter on his table, and its postmark taunted him: Pray for Peace.

And so the lonely debate progressed. Late that afternoon he made up his mind. Taking a sheet of college stationery, he sat at his desk for two hours, composing a careful letter which he spent another hour editing and rewriting. He then walked past the karate hall and into the empty town; at the post o�ce he registered the letter and had it stamped Pray for Peace. He placed the receipt carefully in his wallet. When he got back to his room he found Dr. Rubin, his chemistry professor, knocking on the door. ‘Come in,’ Joe said, and the frail little man sat primly on a straight-backed chair.

Placing Joe’s examination paper on the table, he said, in a complaining voice, ‘Joe, that was a miserable performance.’

‘I know. I’m dropping out.’

‘No need to,’ Rubin said in his nasal whine. He turned back the cover and disclosed the mark, B–. For some moments Joe looked at this unmerited grade, trying to decipher why Rubin had awarded it. Then, as if from an unreal distance, he heard Rubin saying, ‘I saw you at the peace rally. I saw the policeman club you on the head. I watched you during my exam and learned later that you didn’t even report for the others. But I will testify to the guidance people that you earned a B–, in my class and that you were too ill to take the later exams. Joe, without falsifying you can claim head damage … stay in the university …’

‘Not any more,’ Joe said. From his wallet he extracted the receipt for a letter he had mailed to his draft board and from his desk he produced his work sheets, and when Professor Rubin read them he grew respectful, for it was a letter that he might have written had he been a student:

I have reviewed carefully my position both in the draft and in my nation … I have concluded that I can no longer honestly cooperate with a system that is basically immoral nor with a war that is historically wrong … I am therefore returning to you in this letter my registration card and my classi�cation card … I shall refuse to report any further to your board and I reject herewith my classi�cation of 2-S. I am aware of what I am doing, why I am doing it, and what I can expect in retaliation.

There was more, some of it obviously the work of a man not yet twenty-one, all of it adding up to the picture of a human being reaching a moral decision and announcing himself as willing to abide by any consequences that might follow.

Rubin folded the letter, placed the receipt on top, and handed both back to Joe. ‘Things now become quite di�erent,’ he said. ‘The B– I’ve given you and the medical excuse I o�er could become quite important when you get out of jail and want to gain readmission.’

‘You think it’ll mean jail?’ Joe asked. ‘Probably. What you’d better do, Joe, is talk with my wife. She an expert in this, you know.’

position that is totally insane. If we do that, the alternatives become a little clearer. The government’s position is contradictory, immoral, illegal and, in my opinion, unconstitutional, in that no war has been declared. This means there is no legal base for the actions they will take against you. On the other hand, by turning in your draft card and rejecting the system, you’ve struck at the heart of a cooperative democracy and you must be punished. Our job is to work out precisely where you stand.

‘You can do one of three things. On the second of January you can report to your draft board, ask them to ignore your letter and request reinstatement. This will be granted quickly, because no one wants trouble. In your case, we can certify mental disturbance after having been unlawfully struck on the head. All this I can easily arrange, and I am legally obligated to recommend it.’

When Joe shook his head negatively, she continued: ‘Rejecting that, you automatically revert to 1-A status and are stigmatized as legally delinquent. You can be arrested on sight, but until someone presses the issue, you probably won’t be, so now you face two options. You can leave the university and try to hide out within the United States. There’s an e�ective underground which will do what it can to help. It operates in all cities … �nds jobs for men like you … gets you clothes … gives you food. You would be astonished at the good men and women who are willing to hide you and provide some kind of living for you. But it isn’t easy, because the good �rms insist upon seeing your draft card, which means that when you’re delinquent you can’t safely apply for anything but underground work.

‘Your third option is to leave the country … become a political refugee. But before you jump at this, I am obligated to warn you that even if you go so far as to become a citizen of another country, on the day you set foot back in the United States, you’ll be arrested and you’ll face a penitentiary term. And don’t rely on hopes of a general amnesty, either, because America is very revengeful and doesn’t go in for amnesty. At the end of World War II President Truman initiated the �rst amnesty board in our history. It reviewed over one hundred thousand cases of draft-dodging and deserting,

and in the end it granted amnesty to �ve thousand. You must face the fact that ultimately you will go to jail.’

Joe took a deep breath and said �rmly, ‘I can’t take back my draft card.’

Mrs. Rubin nodded approvingly. She was always pleased when a young man said ‘I can’t’ rather than ‘I won’t,’ because the former indicated a moral conviction that could not be set aside, whereas the latter implied mere personal preference without a solid footing. The I-won’t boys got into trouble; the I-can’t, into jail.

The atmosphere in the narrow room was tense, and Mrs. Rubin broke it by saying, ‘If you do change your mind and take your draft card back, we can still o�er you several attractive ways to beat the system. Lots of girls would be willing to marry you … have a baby real quick. Or we can �nd a minister who will coach you in how to be a conscientious objector. You’re not an atheist, are you? Or we have several doctors who will certify psychological disturbances. With that knock on the head we might even manage a straight medical certi�cate. Or you could confess to gross immorality.’

‘Not interested,’ Joe said.

At this point Mrs. Rubin began laughing, shyly but with an underlying sense of delight. ‘That leaves only one escape. But it’s a dilly. I like it because it highlights the insanity in which we �nd ourselves. If you’re really determined to beat the draft, the simple solution is to assemble two like-minded friends and enter into a conspiracy to shoot a bald eagle.’

‘What?’ Joe gasped.

‘Any young man who commits a felony as opposed to a misdemeanor is ineligible to serve in our armed forces. Since murder is a felony, if you commit murder you beat the draft, but this is rather a sti� price to pay for temporary freedom, because you might hang. There are lots of other felonies you wouldn’t want to bother with, like treason. The simplest felony on the books is shooting a bald eagle. But who knows where to �nd a bald eagle? So what you do is to enter into a conspiracy to shoot one, and then you don’t even have to bother with �nding the damned thing.’

Joe was not a man who laughed much, but the concept of his sneaking into a darkened hallway, knocking three times on a closed door and whispering, ‘Let’s go for that eagle, gang,’ was so appropriate to these times, that he chuckled, and in this more relaxed ambience Mrs. Rubin said, ‘So we face up to the fact that you’ve chosen a di�cult course. It would be easier if you could count on some �nancial aid from your parents. Your father?’

‘A born loser.’

‘Your mother?’

‘She collects Green Stamps.’

He volunteered no more, so Mrs. Rubin dropped the subject. ‘In principle what do you propose doing?’ she asked.

‘At this point I can’t say.’

‘Legally I’m not allowed to make up your mind for you. But if you care to ask me direct questions, I’ll answer them.’

More than three minutes passed—a long time for silence between two people—before Joe said hesitantly, ‘I was sickened by the way the police beat up on my roommate. When they hit me it didn’t matter too much. That was an accident. But they were gunning for him and they really unloaded.’

Mrs. Rubin said nothing, and after another long pause Joe asked, ‘Suppose I did want to get out of the country? Then what?’

Mrs. Rubin took a freshly sharpened pencil and began doodling in orderly patterns. ‘You would have two obvious choices, Mexico or Canada. The �rst is most di�cult. Strange language. Strange customs and no sympathy with student radicals. Mexico’s not advisable. Canada is good. Lots of people up there understand your problems and sympathize. But it’s di�cult to get in. Along our western states the Canadian immigration authorities turn back obvious draft dodgers and notify the American police. To make it you’ve got to hook up with our underground railway out of New York.’

‘How would I do that?’

‘There’s a church on Washington Square in New York—that’s in Greenwich Village. You report there and they ship you north.’

Joe said nothing, so Mrs. Rubin concluded: ‘I am legally required to advise you to go to jail now, and I so recommend.’ She took down a form, carefully noted Joe’s name and university address, and wrote: ‘I recommend that this young man submit himself now for his jail sentence.’

But when Joe rose to leave she accompanied him to the door, grasping his hand and whispering, ‘My personal opinion is that you ought to �ee this insanity. Go to Samarkand or Pretoria or Marrakech. Youth’s a time for dreaming and adventure, not war. Go to jail when you’re forty, because then—who gives a damn?’

On New Year’s Day 1969 Joe started his trip into exile, and it was typical of him that he chose not the easy southern route to Boston but rather the ice-bound highways of the north, and it did not occur to him to call his ine�ectual parents: his father would snarl and his mother would cry, and between them they would say not one relevant thing.

He hitchhiked up California’s central valley and at Sacramento struck east toward Reno. The high passes were covered with snow, so that at times he could look up on either side and see solid banks three or four feet above his head. He then cut across bleak and empty Nevada to Salt Lake City, where he wasted some days getting the feel of the Mormon capital, but his �rst moments of grandeur— the excitement he sought, the feel of America—came later when he crossed the vast and barren wastes of Wyoming. The road swept eastward in noble curves through mountains and across limitless plains. He traveled �fty or sixty miles at a clip without seeing so much as a gasoline station, and the occasional tiny town looked like a steer strayed from the herd and lost in the immensity of sky and wasteland.

At the Continental Divide, that chain of mountains separating the western lands Joe had known from the eastern he was about to see, a snowstorm overtook him, and as he rode through the night on a truck bound for Cheyenne, the headlights re�ected back from a million glittering �akes.

‘This is some country,’ he mumbled approvingly to the truck driver, who was worried about the road ahead and growled, ‘They shoulda left it with the Indians.’

East of Rawlins the snowdrifts became so deep that the plows bogged down, forcing a long line of trucks and venturesome private cars to halt at the crossroads where Route 130 cut in from the south. Drivers and passengers crowded into a small diner, where the harassed owner, caught without waitresses, was dishing out co�ee and rolls.

‘This is some country,’ Joe said to a group huddling about a heater vent.

‘You headed east or west?’ one of the men asked. ‘East.’

‘You not in service?’ an older man asked, indicating Joe’s hair. ‘No.’

What happened next Joe could not reconstruct later, but somehow the men got the idea that he was heading east to report for induction into the army, and they insisted upon paying for his co�ee and buying him cigarettes. ‘Best years I ever spent were in the army,’ one of the drivers said.

‘They taught me how to keep my nose clean,’ another agreed.

An older man broke in to say, ‘I spent three wonderful years in Japan.’ He laughed. ‘From Guadalcanal to Leyte Gulf, I fought the little yellow bastards; from Osaka to Tokyo, I slept with them—and I’d do both all over again.’

‘Them Japanese girls A-okay?’ a younger man asked.

‘The best.’

‘Is the country as interesting east of here?’ Joe ask.

‘Interesting?’ the older man snorted. ‘There’s not an inch of Japan that isn’t interesting. You ever hear of Nikko? Son, when you’re in Vietnam and get some leave, haul your ass up to Tokyo and catch the train to Nikko. You’ll see something.’

‘I meant this country. Is it good east of here?’

‘This is a beautiful country, from the Golden Gate to Brooklyn Bridge,’ one of the drivers said reverently, ‘and don’t you ever forget it.’

This note of patriotism induced a di�erent mood, and one of the drivers said, ‘They’re sure gonna cut hell out of that hair when you join the army, son. You’ll be better for it.’

The drivers agreed that Joe would pro�t from the discipline of army life, and as he listened to them extolling its bene�ts he thought how cowardly he was to allow them to think that he was about to follow in their steps when in fact he was using their hospitality to escape. He swallowed his ignominy and thought: If I told them I was dodging the draft they’d probably stomp me to death.

Ashamed of such duplicity, he left the diner and walked into the storm, where headlights from cars pulling o� the road cast strange beams into the snowy night. At times his universe seemed minute, no larger than the circle formed by the �akes, but at other times, when the lights had vanished, it broadened out to an in�nite prairie, silent and of enormous dimension. As he stood in the storm, caught within the circle of light, yet thrust outward to the horizon, he gained a sense of the world, that never-known miracle of which he would henceforth be a sentient part.

At the same time he achieved his �rst appreciation of America, vast and inchoate in the darkness which engulfed it. ‘This is a land worth �ghting for,’ he muttered, feeling no contradiction in being a man running away from the draft yet inspired to �ght for a land which he sensed was good. So far as he could judge, the most notable patriot he had met in the last four years had been Mrs. Rubin, a Jewish housewife perched in the basement of a Presbyterian church, trying to bring some kind of order out of the chaos her country had fallen into.

As soon as he hit New York he headed for Washington Square, where the church he sought looked exactly like the one he had left in California and where the Quaker woman counseling him could have been Mrs. Rubin’s sister. She assured him that jobs were available, but that he’d have to be careful in seeking them: ‘You’ve got to avoid places where the owner might want to see your draft

card. And watch out for the older men in the construction unions. They’re very patriotic and they’ll insist that you be patriotic too … in their way. But here’s an address that might work. They’re tearing down an old building and they’ll be happy to have anyone with a strong back.’

He reported to a site near Gramercy Park, where there was a huge hole in the ground next to a large private house that was being demolished. The foreman explained: ‘The hitch is that some nuts want to save the ceilings. Seems they were carved a hundred years ago. Your job is to get them down without pulverizing them.’ Before Joe could say anything, the foreman thrust a crowbar in his hands, shouting, ‘Remember, if we wanted them goddamn ceilings torn apart we’d use the wrecking ball. We want ’em in one piece.’ A little later an assistant came into the room where Joe was working from a sca�old and whispered, ‘If anyone asks about your union card, you’re a private artist saving the ceiling for a museum.’

‘What museum?’

‘New York Museum of Architecture and Design,’ the man said promptly. ‘There ain’t none with that name and it’ll keep the union guy busy till next week �gurin’ it out.’

The work was dusty and back-breaking, but when Joe climbed down for a rest, the assistant said, ‘Imagine you’re Michelangelo. He worked up there twenty years, I saw it in the movies. “You’ll work there if I say so!” ’ He continued bellowing in a theatrical voice, ‘ “I’m the Pope. Get the hell back to work.” ’

At night Joe slept in a �ophouse recommended to him by the woman at the church, and he was so tired that he dropped o� to sleep immediately. His neighborhood was a lively one, and during the day he saw young people, including many attractive girls, gathering in the streets, but he could not bring himself to join them. His immediate responsibility was to earn enough money to make the break for Canada.

On his last visit to the church his counselor gave him an address in New Haven, and told him, ‘Report after six in the evening. This o�ce is run by Yale men and they attend classes during the day.’

He left New York with the impression that it was probably a hundred times larger than he had guessed, a hundred times more interesting. At some future time, when circumstances were more congenial, he would like to test himself against this city, against its indi�erence and beautiful girls. ‘I wonder if I could handle New York?’ he asked himself as he headed north.

He landed in New Haven at mid-afternoon, and as the woman in New York had predicted, the underground o�ce was closed, so he drifted about the ugly city. It was a cold day, and the more co�ee he drank in order to share the warmth of the restaurants, the more his bladder su�ered from the icy wind, and he was most uncomfortable, but when the counseling o�ce opened he was more than repaid.

The counselor was a professor of poetry with an Oxford background, so Joe concluded that he must have been a Rhodes Scholar. To protect himself legally, the professor, a young man with enthusiastic ideas, advised Joe to surrender and go to jail, but when Joe refused, the professor leaned back in his chair and said, ‘When I was about your age I went to Europe with hosannas in my ears. You’ll be going as a criminal. Plus ça change, plus ce n’est pas la même chose.’

‘I haven’t decided yet,’ Joe said.

‘Good God! Aren’t you the lad I was supposed to meet from Alabama?’

‘California.’

‘My dear fellow, forgive me. We get these urgent messages and we don’t really spend the time we should. There’s a deserter being smuggled through here this evening on his way to Canada, and I assumed that you were he.’ He struck himself on the forehead and said, ‘Good God! One look at your hair should have satis�ed me you hadn’t been in the army. I’m going to turn you over to one of our chaps who specializes in draft delinquency. I really don’t know the facts.’ He called for a student named Jellinek, but got no response, so he looked outside the door to see if the deserter from Alabama had arrived, then sank back into his chair, adjusting his legs beneath him as if he had no bones.

Speaking rapidly and with mounting enthusiasm, he said, ‘Since both of our people are late we may as well exchange con�dences. If I were you I’d head straight for Europe. Even if I had only ten dollars I’d go. How? Work on a cattle boat. Ensnare a rich widow. God knows how I’d do it, but I’d do it. I’d see the Van Eyck altarpiece at Ghent, the Brueghels at Vienna, the Velázquezes in the Prado. I’d want to see Weimar and Chartres and San Gimignano and Split in Yugoslavia. Do it, young man, no matter the cost. Don’t waste these years in hiding in Canada. There’s nothing you can learn there that you can’t learn hiding in Montana. Go to Europe, educate yourself, and when this madness is over, come back and go to jail. Because if you go into your cell with ideas and visions, the years of imprisonment won’t be wasted and you may come out a man of substance.’

‘How would I get to Europe … with no money, that is?’

‘Good God, money is the cheapest thing on this earth, but with you boys, it seems to be the overriding concern.’ He leaped from his chair and stormed about the room, scratching his head. Suddenly he stopped and pointed a long �nger. ‘I know just the place for you. Get to Europe any way you can and drift down the coast of Spain to a place called Torremolinos. All sorts of bars, dance halls. A smart chap can always make a living there.’

‘My Spanish isn’t too good.’

‘In Torremolinos they speak everything else but. How’s your Swedish?’ He laughed and ran to the door again to check on his missing Alabaman. Finding no one, he returned to his desk and said, ‘In Boston you’ll �nd a splendid group of people. They’ll give you surprising assistance. There’s a girl up there … her name is … Jellinek will know when he gets here.’

This exhausted what he could tell Joe, so the two wasted the better part of an hour discussing the university situation in California. The professor had a high opinion of the California schools and said he might like to teach there one of these days. ‘It’s where the action is,’ he said, and Joe thought that no matter where he said he came from, someone always said, ‘That’s where the action is.’ It was a phrase without meaning.

exile was one of the brighter men at Yale; obviously he was one of the most popular, yet he openly espoused �ight as the only honorable alternative.

As the night wore on, the professor took Joe aside and said, ‘I just had an idea. It’s not a very good one but it might work. Joe, how tough a man are you?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘Can you defend yourself? I don’t mean with your �sts. Against heroin? Against the whole complex?’

‘I keep my nose clean.’

‘I �gured. If you do get to Torremolinos and you’re broke and the police are breathing down your neck and threatening to throw you out of Spain, there’s a name you might look up … at your own risk. Write it down. Paxton Fell. He has money.’

When the time came to leave, one of the students took Joe aside and slipped him a handful of bills. The student said, ‘Good luck,’ and they parted.

He arrived in Boston at sunset, lean and shaggy and ill-tempered. It took him some time to locate the Cast Iron Moth. He had found the address in the phone book but was quite helpless when it came to spotting the street, for it lay in that maze of alleys o� Washington Street and he must have come close to it two or three times without realizing that he was in the vicinity. He had always disliked asking strangers for advice and tried to zero in on his own, without any luck. Finally he had to ask a man where the Moth was, feeling an ass as he pronounced the name, and the man said, ‘You just passed it,’ and there it was.

Joe decided to spend some of the Yale money on a good meal, so he entered as a customer, but he must have been very transparent, for the doorman said, ‘I suppose you want to see Gretchen Cole.’

‘I want to eat,’ Joe said.

The menu was on the expensive side but o�ered a good selection of seafood, which Joe had grown accustomed to in the Portuguese restaurants of Southern California. He found the meal better than