BY:ALEJANDRA

Afew weeks ago, we met with migrant senator Karina Ruiz, whom we had previously interviewed over Zoom. This time, the conversation was direct, honest, and deeply enriching. We discussed the following:

Alejandra Icela Martínez Rodríguez: Why address migration issues at the Senate?

Senator Karina Ruiz: The chapter I wrote is specifically about creating legislation from a migrant’s perspective. We have been overlooked for a long time. Migrants are not adequately included in the policies or laws of our country, even though we contribute roughly 3.4% of Mexico’s GDP through remittances, and we are not recognized.

My fellow Mexicans tell me: we are not second- or third-class citizens; we are Mexicans who have faced family separation, discrimination, harassment from authorities, and now this situation with the current U.S. administration. I tell them: “In 2010 I lived in Arizona under SB 170, the ‘Show me your papers’ law.” We experienced that in the state and resisted. Now it’s nationwide. And we will keep resisting. I have faith: legislation must address policies that are friendly to migrants and migration because migrants are not a problem; we are an opportunity.

That is how countries can grow and benefit from the talent that comes from other places. But if we don’t create laws to include migrants in the formal economy, we will never see the advantages, and they will only become—like they say in the United States—a public burden, which we are not.

AIMR: Who is this book intended for?

KR: The book is aimed at academics who participated and migrant communities, helping them understand how they are seen from legislative, academic, and civil society viewpoints. It also targets legislators to better grasp what it means to view migration through a labor-inclusion perspective. I often discuss the freedom to

Drawing from her personal experience, Karina Ruiz—Mexico’s first migrant senator— argues that migration is more an opportunity than a problem. Her work in the Senate aims to create pathways for Mexico to include migrants with rights and without discrimination.

We are more than just remittances; we are human beings; we are Mexicans

work. In the United States, there is a program called eVerify. It checks people’s documents to determine whether they are authorized to work. don’t believe this is good policy. Besides costing taxpayers money, there should not be a system where the government decides whether someone can or cannot work and earn a living through their labor. Work represents dignity. What governments should do—and I say this as a legislator in Mexico—is create visas, programs, laws, and regulations so workers are included in the formal economy and are not vulnerable to labor abuse, extortion, or other harmful situations that lead to violence and social issues in our country and others.

From my own experience in the United States, if my family had been granted a work visa, we might have gone to work as planned. My parents said, “We are going for one year, to work, save money, and come back to open a business.” They left my siblings and their grandchildren here. There is always a strong connection to home. You don’t leave just because. Why doesn’t Mexico learn from that experience? Maybe people from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, or Haiti didn’t want to go, but conditions pushed them.

Let’s create laws for the migrants here the same way we would want other countries to create laws for ours.

AIMR: There’s a narrative that says, “New migrants are taking our jobs.” How can Mexico avoid becoming like the United States in this regard?

To my Mexican people, I say: Look at the U.S. as a mirror—its story is false. Mexicans did not take anyone’s job

KR: In Mexico, this may seem new, but after living 26 years in the U.S., I can tell you it’s an old story from the racist, xenophobic far right, which has never recognized the need for migrant labor and talent—not just from Mexico but from around the world.

We have had to outdo our parents at work because, often, working without proper documents means you can’t leave a job easily. You endure labor abuse and sexual harassment. I experienced this firsthand as an immigrant. I couldn’t leave my job because didn’t have a work permit. I had to do the work of two people because the U.S. citizen could simply quit and find another job. That wasn’t my reality. I didn’t take anyone’s opportunity.

A Latina woman once told me that her son didn’t get a scholarship because of me. At that time, I was opposing Proposition 300 in Arizona, which would have tripled my tuition. As an undocumented student, every dollar I earned went toward my education. I worked to cover all expenses. I attended school and worked 40 hours a week, including 12–13-hour shifts on weekends, because I needed to cut back my hours during the week to attend classes.

And that same woman told me her son couldn’t get a scholarship when I wasn’t even eligible for state or federal aid because of my immigration status.

Migrants, especially those without regular status, don’t have access to benefits—and even those who are regularized, if they contribute, should have access to education. What society doesn’t want its people to study?

A racist society that doesn’t understand that an educated workforce builds a stronger country. No one takes jobs away. There is work for everyone. The more people arrive, the more we will need.

If we don’t want Mexico to end up like the United States—with 11 million undocumented people from Central America, Haiti, or the Caribbean in ten years—we need to act now. We should develop programs to integrate migrants into the formal economy, promote the circular economy my parents envisioned, and support Central American nations. Migration from Central America is a Latin American issue, spanning from the U.S. to the Southern Cone and the Caribbean. If new arrivals initially pose an economic cost in healthcare or education, investing in their dignity and labor inclusion will prevent them from becoming a burden. In the medium and long term, migrants can benefit the country, as studies in other nations demonstrate.

It is crucial to see ourselves in that mirror and remember that migrants are not a problem, nor do they bring crime. We avoid crime precisely to stay off the authorities’ radar. We need public policies and laws that genuinely support migration and consider the full context. Many people don’t even want to stay in Mexico; they want to work, save money, and return to their families.

This is what we need to learn so we don’t repeat the exclusionary system the United States has—one that blocks circular migration instead of supporting it.

AIMR: And you experienced it firsthand, senator.

KR: Yes. Here we are in Mexico’s Senate, as the first migrant senator, representing, fighting, and raising my voice for all my people beyond the border.

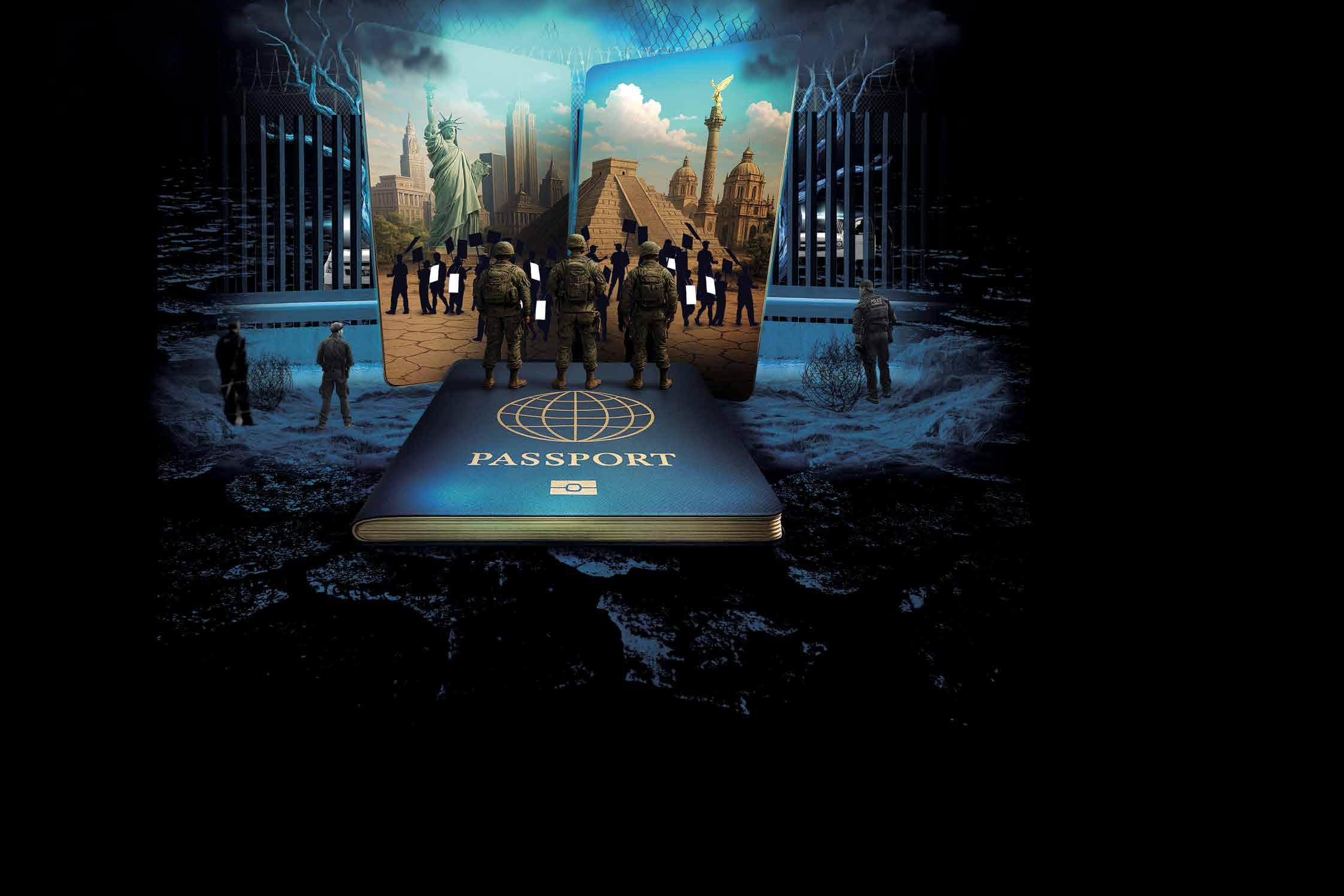

MEXICO AND THE UNITED STATES SHARE A BORDER BUT APPROACH SECURITY FROM OPPOSITE ANGLES—ONE FOCUSED ON SOCIAL PREVENTION AND COMMUNITY WELL-BEING, THE OTHER ON BORDER DEFENSE AND EXTERNAL THREATS. AS VIOLENCE TRENDS SHIFT AND COOPERATION EXPANDS, BOTH COUNTRIES FACE THE CHALLENGE OF TURNING CONTRASTING VISIONS INTO A BALANCED, SOVEREIGN AND EFFECTIVE SECURITY STRATEGY FOR THE ENTIRE REGION.

BY:MANUEL ANTONIO VÁZQUEZ VALADEZ*

ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

Mexico and the United States share the same geography, but they see security from very different angles. One prioritizes social prevention, community well-being and the rebuilding of social fabric; the other focuses on defending its borders and controlling external threats. Today, their common challenge is turning that difference into an alliance that makes the entire region safer and fairer.

The U.S.–Mexico border is both a meeting point and a point of tension between two distinct security visions. For Washington, the movement of drugs and migrants is a national-security threat. For Mexico City, these are public-security issues tied to inequality and the breakdown of community life. While the United States builds walls and expands surveillance, Mexico invests in social and community programs that address the roots of violence. The contrast is not only political; it reveals two different ways of imagining peace.

THE U.S. VISION: SECURITY AS DEFENSE

Since the late 20th century, the United States has treated synthetic-drug trafficking and migration flows as matters of national survival. The fentanyl epidemic, which claims more than seventy thousand lives each year, has mobilized the security apparatus: the Pentagon, intelligence agencies and customs officials work together to stop drugs and people from crossing illegally.

This approach turns a social crisis into a geopolitical one. It frames the phenomenon as something to be stopped before it reaches the border, even though addiction, demand and profits originate inside the United States. In recent years, treatment, harm reduction and education programs have grown. Experts agree these public-health efforts are essential to confronting the fentanyl crisis. Still, the balance remains tilted toward containment, and the political debate continues to be shaped by a logic of control.

THE MEXICAN VISION: SECURITY AS PEACEBUILDING

Mexico’s approach of the past six years rests on four pillars of public-security policy. The first is the strengthening of the National Guard, a civilian institution with territorial presence and local coordination.

The second is the network of Peacebuilding Committees, where institutions, local governments and communities analyze incidents and coordinate joint actions.

The third focuses on addressing the root causes of violence through education, health and employment, with programs such as Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro, Sembrando Vida and the Universidades del Bienestar.

The fourth is intelligence—using reliable information to prevent crime and act with greater precision and fewer confrontations.

TOGETHER, THESE PILLARS CENTER ON BUILDING PEACE IN COMMUNITIES.

According to data from the National Public Security System, presented during federal morning briefings, from September 2024 to April 2025 the daily average of intentional homicides fell by roughly 25%. April 2025 registered the lowest figure since 2016. Compared with April 2020, homicides were down 33.3%, and between 2018 and 2025 the annual average dropped 27.3%.

Impunity and institutional weakness persist, but these figures show real progress toward peace after more than a decade of continuous increases in violence.

Mexico’s strategy goes beyond international agreements. On the ground, the federal government maintains an active agenda that combines security, social programs and community rebuilding. The Interior Ministry coordinates community initiatives, peace outreach events, service fairs, public-space recovery and voluntary-disarmament campaigns involving millions of people nationwide. Combined with the work of State and Regional Peace Committees, these efforts show that security is also built from the bottom up, through citizen participation and cooperation among civil, military and social institutions. Addressing root causes—active prevention—has become a state policy that supports the steady decline in violence.

SHARED SECURITY

Security is one of the clearest areas where the Mexican and U.S. visions converge—and sometimes collide. For Mexico, it is a public good that requires coexistence, development and social justice. For the United States, it is a matter of national defense and border control. Both want the same outcome: less violence, safer communities and preserved sovereignty, even if they start from different premises.

In Washington, success is often measured in seizures and arrests. In Mexico, it is measured in reduced homicides and expanded opportunities. In reality, both operate with mixed agendas: police action and intelligence, paired with social and community programs. The difference lies in emphasis. Mexico advances control and prevention simultaneously; the United States tends to prioritize external-border protection. A

sponsibility and respect for national sovereignty. The strategy seeks continued collaboration with the United States against drug trafficking, arms smuggling and money laundering—while avoiding any form of foreign interference.

This approach rests on three principles: ensuring transparency and political oversight of agreements; clearly defining responsibilities to prevent external operations on Mexican soil; and evaluating results not only by seizures or arrests, but by their impact on reducing violence and strengthening institutions.

Mexico has also reinforced its regional diplomacy with a new Undersecretariat for North America, expanding the agenda to include technology, energy and production chains such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence. The guiding idea is that shared security does not mean dependency, but balance. Mexico must strengthen its own effective, sovereign state policy, while the United States must curb the flow of weapons, regulate chemical precursors and combat money laundering within its own financial system.

The Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, signed in September 2025, reaffirmed that both governments will work to dismantle organized crime through intelligence, joint inspections and precursor-chemical tracking. At the same time, Mexico’s Interior Ministry has reinforced Peace and Security Committees, where civil, military and social forces coordinate community support, institutional presence and violence-prevention efforts. Examples include joint inspection programs in Manzanillo, Lázaro Cárdenas, Tijuana and Nuevo Laredo, alongside municipal social programs and police reforms that have helped reduce crime. Challenges remain—impunity in Mexico, gun proliferation and social inequality in the United States. But both governments now recognize that security cannot be built through isolation or blame, but through cooperation, shared responsibility and mutual respect for sovereignty.

FROM CONFRONTATION TO COEXISTENCE

The real test is not who controls the border better, but who understands security more deeply. The United States must look inward—toward its demand for psychoactive substances, its healthcare system and its gun culture. Mexico must continue strengthening justice, professionalizing police forces and ensuring that prevention reaches those who need it most.

Recent progress, including the drop in homicides and renewed bilateral cooperation, shows that a different path is possible. Mexico’s model—grounded in strong institutions, community involvement, intelligence and social investment—offers a humane alternative to punitive approaches that have failed across the region.

Security, at its core, is not a wall or a patrol. It is the ability to live without fear. Beyond political cycles, Mexico and the United States will need to deepen their understanding that a shared geography means a shared responsibility. The border region—so often portrayed as a dividing line—can become a laboratory for coexistence, where two visions, one centered on defense and the other on care, learn to complement each other. Together, they can build a safer and fairer region for the people who live on both sides.

* The author is a political scientist and specialist in global governance

Beyond official agreements and migration restrictions, Mexico and Canada sustain an ongoing relationship through universities, artists, Indigenous communities, and cultural projects that foster knowledge, memory, and empathy.

BY GRACIELA MARTÍNEZ-ZALCE*

The reinstatement of the visa requirement for Mexicans in 2024 revealed a paradox: while both governments celebrated eighty years of friendship with speeches and commemorations, borders became more restrictive. Still, diplomacy doesn’t always rely on passports. Ideas, art, and education can travel without consular stamps. When official channels shut down, academic and cultural connections keep the dialogue alive.

For over thirty years, universities, researchers, and artists from both countries have built an invisible network of collaboration. During this period, academic diplomacy has evolved into a form of listening, shared learning, and even resistance against official narratives. Unlike trade agreements, these partnerships do not aim for immediate profits but foster mutual understanding.

ACADEMIA AS A BRIDGE

Academic diplomacy is often seen as part of public diplomacy: mobility programs, exchanges, agreements, and research networks. But its scope is broader. It is also practiced through jointly supervised theses, hybrid seminars, and community workshops where realities are compared, and official discourses are challenged. The value of these spaces lies in their ability to go beyond the nation-state. They connect students who explore binational issues, researchers who recover overlooked histories, and artists who challenge stereotypes. Universities do more than just reproduce knowledge; they also reshape it—and in doing so, they foster trust between societies that learn to see each other beyond geopolitics. In Mexico, UNAM has played a key role. The establishment of its School of Extension in Gatineau, Quebec, in 1995, along with the Extraordinary Chair in Canadian Studies Margaret Atwood / Alanis Obomsawin / Gabrielle Roy in 2002, created a lasting Mexican academic presence in Canada.

The latter, developed in collaboration with the Canadian Embassy and CISAN, added the name of Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin in 2022, acknowledging the importance of Indigenous and decolonial perspectives in literary and cultural studies.

From these initiatives emerged three key spaces: the Permanent Seminar on Canadian Studies, the Binational Thesis Workshop, and the Allied Seminar on the Study of Indigenous Peoples in North America. All share a common mission: to train the next generation of Mexican and Canadian scholars capable of viewing the continent through its connections rather than its borders.

If academia builds bridges through ideas, art does so through symbols. Painting, cinema, literature, and design have served as means of connection between the two nations. In 2000, the National Gallery of Canada and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts hosted a major exhibition on twentieth-century Mexican art. Conversely, in 1999, Mexico showcased an exhibit dedicated to the Group of Seven, a symbol of Canadian landscape painting.

These exhibitions—along with retrospectives like Alan Glass’s Surprising Discovery (2023)—show that cultural diplomacy doesn’t always come from embassies. It often happens in museum

Academic and cultural diplomacy between Mexico and Canada shows that collaboration can persist without visas, using ideas, art, and shared knowledge to rebuild trust when politics fall short.

halls, exhibition catalogs, and studios where artists from both countries meet and collaborate.

Yet they also reveal a lingering obligation: the need to rebuild scattered archives, recover lost catalogs, and document the presence of Mexican artists in Canadian galleries and vice versa. Reconstructing that memory would mean writing the history of how Mexico and Canada have perceived each other through art.

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES: DIPLOMACY FROM THE ROOTS

In recent years, one of the most transformative processes has been the inclusion of Indigenous voices in the bilateral relationship. Indigenous peoples in Mexico and Canada have formed autonomous connections based on land defense, language preservation, and criticism of extractivism.

During the pandemic, virtual roundtables connected communities from both countries to discuss the loss of Indigenous languages and explore digital activism. In 2021, Anishinaabe artist Rolande Souliere teamed up with the Zapotec collective Tlacolulokos on a mural in Oaxaca that condemned gentrification and the touristic idealization of Indigenous cultures. In these encounters, cultural diplomacy was conveyed through pigments rather than speeches.

Indigenous, academic and artistic exchanges have created a resilient binational network, proving that meaningful diplomacy emerges from communities, creativity and mutual listening— not official protocols.

In 2023, a joint exhibition in Canada, Mexico–Canada: A Woven Friendship, showcased textiles from Mexican Indigenous communities at a festival honoring Indigenous peoples. For the first time, Mexican Indigenous textile art took center stage in a Canadian exhibit—proof that diplomacy can also be woven with thread and needle.

TEXTILES THAT SPEAK OF GENDER

Embroidery serves as a delicate cultural bridge for memory and protest. In Mexico, women’s collectives have embroidered the names of femicide victims; in Canada, textile art projects have confronted colonial violence. This shared impulse gave rise to the project Transform: Engaging with Young People for Social Change, led by McGill University’s Participatory Cultures Lab and CISAN–UNAM. Youth from Mexico, Canada, and multiple African countries collaborated through photographs and embroidery to explore gender, climate justice, and queer activism.

The works traveled from UNAM’s main campus in Mexico City to galleries in Halifax and Montreal, demonstrating how art can foster empathy where politics creates division. Each stitch becomes a form of diplomacy.

A DIPLOMACY THAT LISTENS

The relationship between Mexico and Canada has experienced cycles of enthusiasm and bureaucratic silence. However, one conviction remains: shared knowledge fosters stability when politics falter. Academic and cultural diplomacy do not replace state diplomacy, but they complement it. Where governments pursue electoral interests, academic and artistic communities operate out of intellectual dedication. When official policies withdraw, cultural networks move forward.

* RESEARCHER

The bridges that don’t require visas are built on curiosity, creativity, and determination. Thanks to those who research, teach, translate, create, and engage in dialogue, mutual understanding between Mexico and Canada stays possible.

They have an agreement with the Ethnography Laboratory at the Multidisciplinary Research Center on Chiapas and the Southern Border (CIMSUR–UNAM). They describe themselves as an autonomous, self-managed collective dedicated to researching, producing, and sharing textile practices from the Chiapas Highlands.

For over twenty years, Colectiva Malacate has brought together 100 Indigenous women to preserve traditional weaving, reclaim their cultural knowledge, and build economic independence in the Chiapas Highlands

They offer classes and workshops in traditional weaving and embroidery. Preserving the traditional weaving and embroidery techniques of the Chiapas Highlands—and recognizing the women who protect this knowledge—are the foundations on which Colectiva Malacate was founded more than twenty years ago.

“I was interested in understanding textile craftsmanship as a means of cultural transmission and resistance to globalization,” explained Karla Pérez Cánovas in an interview with El Heraldo de México. She is the creator of the collective, which began as a research project titled ‘Textile craftsmanship as a means of cultural transmission and resistance to globalization in the municipality of Zinacantán, Chiapas.’

“I also wanted to understand the relationship between textile practice and the daily lives of the weavers,” said the

Women together can transform our lives, and we have the strength to do it together’ KARLA PÉREZ CÁNOVAS

anthropologist from Mexico’s National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH).

The research took about two years, and once finished, it shifted from an academic project to a lifelong pursuit.

When I finished, I decided to take a new path and collaborate with the women I had been working with,” Pérez Cánovas said. She felt responsible for them and wanted to show reciprocity—“not only for what I learned from them, but because, as anthropologists, when we work in community settings, we must act responsibly and reciprocally.”

Today, the group includes 100 women from the Highlands and Jungle regions of Chiapas. “These are women who sustain life in their communities,” she said, describing the maestras whose knowledge was historically undervalued because of local customs. “Weaving and embroidery were simply seen as part of being a woman. Back then, they didn’t regard themselves as knowledge keepers.”

That’s when Karla began a process of self-recognition with them: “You are

+20 years of experience in the collective

maestras because you are the ones who have transmitted this knowledge,” she would tell them. Her work helped elevate the status of women weavers, and new generations are already thinking differently. One example is Lola, who joined the collective on a friend’s recommendation.

“The collective has ignited the idea that, as women, we can move forward independently — that we don’t need anyone else to support us. Our children also learn this; they’re being taught differently,” said Lola, who recently finished her nursing degree.

After over twenty years, Colectiva Malacate has preserved the textile heritage of the Chiapas Highlands and enhanced the value of women’s traditional knowledge. Their activities now include collective research, inviting master’s and doctoral students to conduct studies; teaching waist-loom weaving, embroidery, and natural dyes; and community programs that strengthen “women artisans’ awareness of the value of their work.”

She explained, “We have a project

For me, Malacate is a commitment to the lives of women,artisanto the maestras.’

PÉREZ CÁNOVAS

called ‘Reactivation of traditional and ancient techniques and designs from the Highlands and Jungle regions,’ through which we have created different lines of traditional clothing from each member’s region, ensuring that these techniques are passed down within their communities and that this textile memory is preserved.”

Beyond textile work, embroidery also functions as a social tool. “We’ve used embroidery to express ourselves and discuss many issues, especially social problems,

We also have collaborations called ‘Komun Antel,’ which in Tzotzil means ‘working together in harmony.’ That’s why the compañeras named it—they believe it’s essential to use concepts from their own language,” added the ethnologist.

When asked what this project means to her, Karla reflected: “It has been a path that, alongside my compañeras, has shown me what am capable of achieving as a woman.” And so, Colectiva Malacate continues safeguarding the textile memory of the Chiapas Highlands.

Voices from the capital and the Juárez border unite to demonstrate the impact of this art throughout the country

BY: PATRICIA TEPOZTECO ART: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

In a country as diverse and complex as Mexico, theater acts as a bridge between realities that, at first glance, seem disconnected. From the major stages of Mexico City to independent venues in Ciudad Juárez, creators have found in theater a shared space where generations, regions, and viewpoints come together. This convergence shows that, even in different settings, theater has a single purpose: to listen to what hurts, support what is changing, and defend what resists.

A CITY THAT OPENS DOORS

In Mexico City, where prominent art schools merge with independent venues, a new generation is confidently making its impact on stage. Among them is Lucian Charrier Argayot Martínez, a 15-year-old actor whose gaze reflects a deep truth for youth: theater provides freedom. It’s a space where they can reflect, write, and most importantly, face everyday life with honesty that adults often avoid. His participation in the play Los Muertos—a production that combines creators from the capital with artists from Ciudad Juárez under the direction of French director Sébastien Lange—where he plays a 1968 student and a French-Mexican scientist, shows that theater continues to be a medium that unites different realities and generations.

For Lucian, acting is more than just performing; it involves engaging in a dialogue with stories that express death, life, joy, and memory from a creative and personal perspective. When theater is seen through the eyes of newcomers, it regains its power: that of a living art that challenges and inspires.

JUÁREZ: A STAGE WHERE THEATER BECOMES A COMMUNAL EMBRACE

Hundreds of miles away, along the northern border, the scene changes to a different rhythm and sense of urgency. In Ciudad Juárez, renowned director and playwright Perla de la Rosa, who calls herself a “woman of the theater,” has spent decades creating a space that directly reflects the reality around her. Her work explores the themes that define the city—femicides, migration, inequality—without turning them into spectacles. She approaches these issues with a deeply humanistic perspective, recognizing that theater can both be a breath of life and a reflection. Through her independent project Telón de Arena, Perla

has brought productions, workshops, and community-focused initiatives to neighborhoods, schools, and even places where art rarely reaches.

She recognizes that working in a complex territory presents challenges: building cultural infrastructure, securing additional resources, gaining community support, and the important task of cultivating audiences. She has also learned to turn these challenges into creative energy, training new generations and strengthening community efforts. In doing so, she reaffirms a guiding principle: “Art is resistance and the possibility of dignity.”

The border as a space for innovation and opportunity

Actor Marcos Duarte, after spending twenty years working in film, TV, and theater, has returned to Ciudad Juárez and sees the border as a rich space for creativity.

He recognizes clear challenges —such as improving acting training, decentralizing cultural production, and attracting new audiences—but doesn’t see them as obstacles. Instead, he views them as part of the natural growth of an artistic community that keeps evolving.

With humor and discipline, he emphasizes, as a teacher, the importance of preparation for future generations of actors. He believes that training opens doors and enables local talent to compete with any major city. Simultaneously, he advocates for building community: supporting one another, attending each other’s work, and creating networks to strengthen the scene.

Between challenges and opportunities, Marcos views Juárez not as a limitation but as a chance. Here, theater can connect with reality, audiences, and itself, creating experiences that inspire and transform.

THE SOCIAL ROLE OF THEATER: TO IDENTIFY, REFLECT, AND CHANGE

From the voices of young people in the capital to the cultural resistance at the border, Mexican theater emerges as a vital language because it fosters conversations about migration, death, or violence from a place of empathy. It also gives children, youth, and entire communities a tool to better understand their environment.

Theater doesn’t claim to solve the country’s problems, but it offers a way to face them without fear, to acknowledge them humanely, and to visualize possibilities for change. In this way, it continues to fulfill its purpose: providing a space where, even for a moment, we can all see ourselves in the same shared story.

undoubtedly has a

I’d add that it’s not just used to create politics, because it

Originally a league built mainly for U.S. fans, the NFL has grown into a global powerhouse — and Mexico is now its second-largest international market. With millions of fans, significant economic impacts, and upcoming games, the league’s influence continues to expand internationally.

BY: DIEGO CARREÑO

PHOTOART:IVAN BARRERA

All eyes will focus on the final five weeks of the NFL’s regular season, a league that has become one of the most competitive and exciting in the world thanks to the intensity of every game, where gridiron gladiators risk their bodies to keep their teams in the Hunt for the Playoffs and ultimately lift the Vince Lombardi Trophy at Super Bowl LX. The event will be held on February 8, 2026, at Levi’s Stadium, home of the San Francisco 49ers, and is expected to be a worldwide spectacle.

But how did a product initially created for U.S. fans—where every team stands for a city—become one of Mexico’s top sports leagues? Mexico’s proximity to the United States, along with televised broadcasts, was the first factor that brought the NFL into Mexican homes. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that American football really exploded in

igniting the passion of Mexican fans. Over time, preseason games stopped coming to Mexico due to infrastructure and logistical issues, but the fan base kept growing. Today, an estimated 40 million fans follow the NFL, making it the country’s second-most popular sport—second only to soccer, which

favorite teams, alongside the Miami Dolphins, Pittsburgh Steelers, and San Francisco 49ers.

Cities hosting international NFL games have also experienced significant economic benefits from tourism, including increased transportation, hospitality, merchandise sales, and food and beverage industry growth.

Mexico’s huge fan base makes it the NFL’s second-largest market after the United States. That’s why the league has worked to strengthen its bond with Mexican culture through sporting events, exhibitions, fan interactions with players, and official games—initiatives only possible thanks to support from local businesses and government authorities. All of this aims to promote sports, attract tourism, and keep young people away from harmful activities, as the NFL represents discipline, effort, success, and commitment.

It’s increasingly common to see children and adults wearing NFL jerseys, caps, or accessories on streets, malls, and parks. This isn’t a coincidence—it’s part of a long-term, data-driven marketing strategy carefully carried out.

In 2024, the NFL earned over $23 billion worldwide, mostly from broadcasting rights, sponsorships, ticket sales, and licensed merchandise. Its global expansion in recent years has played a key role in this growth.

The league has also promoted the development of more schools, not just for tackle football but also for flag football, where men and women play side by side without contact, encouraging coexistence and gender equality. Soon, Mexico will host more than one regular-season game annually. Meanwhile, the league keeps expanding into new territories like Australia and France, where it will play for the first time next year.

Without a doubt, the NFL is a model to emulate, demonstrating that sports and financial strategy can work together.

For now, all we can do is relax and enjoy the final stretch of the

season full of surprises.

BY: GONZALO LIRA GALVÁN

Published for the first in the early 1900’s by Lyman Frank Baum as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the tale of Dorothy Gale’s odyssey through the yellow brick road has been synonym of big ideas, explored from a fairy tale realm as bigger than life as possible since it’s first iteration as a novel. Then came the adaptations.

First it was at 1902, as a stage play.

Later, in 1910 a short film by Otis Turner put the world of Oz up on a screen for the first time. But what really stablished L. Frank Baum’s creation as a pop culture phenomenon was 1939 Mervyn LeRoy produced astonishing feature film. Directed by Victor Fleming on the same year he also made Gone With the Wind go into international stardom, his version of Dorothy’s quest remains the most beloved version to date. More than half a century later - ignoring a weird sequel called Return to Oz from 1985 or the animated series from 1990 – a Broadway spectacle appeared to bring back the world of Oz its popularity, while also using it as a reason to explore new ideas by questioning the angle of an already stablished story’s narrative. But first came the book.

Thirty years have passed since Gregory Maguire’s Wicked: The Life and Times

Wicked for Good had the highest grossing opening weekend for a Broadway musical adaptation ever ’

of the Wicked Witch of the West hit

bookshelves in 1995. The novel told the story of the witches popularized in the screen version Fleming directed, and is narrated from a parallel point of view. Dark, political and almost philosophical, Wicked has become the counter part of the well known tale by putting the question mark into never before explored concepts: Is the so-called villain really evil? Who has the narrative control on such a binary world view? And what is the real origin of evil?

Maguire’s book rapidly was adapted. Only this time it was not Hollywood but Broadway where it found a new home.

The story, now centered in Elphaba — the wicked witch of the west— and her friendship with Galinda was a hit almost immediately. Yet it’s main strength was not following The Wizard of Oz as a bible but subverting it. This time Elphaba is not a monster but a woman oppressed by a society so afraid of her power that decides to hunt her as an enemy. Wicked is more a confrontation than an homage, and the stage musical version of it was a success. Until Hollywood appeared.

“It’s not happily ever after and it’s not tragedy either. It’s a consistency”, explains Jon M. Chu, the director of the movie adaptation during an interview at the Wicked For Good premier in New York City, exclusively for El Heraldo de Mexico and Heraldo USA. “It feels so adequate that after a year touring all

I dare

say that whenever you think about The Wizard of Oz, ideas such as social clashes or authoritarian regimes don’t necessarily come to mind.

over the world, the yellow brick road comes to an end in New York for the movie, right where the stage play it’s based on was originated”, expressed producer Mark Platt. Wicked for Good recently became the most successful movie adaptation of a Broadway musical ever, which serves as a testimony on Jon M. Chu’s words on how “this not a sequel to Wicked but a second act for a bigger story”.

Although this second act explores a much darker side of Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) and Galinda’s (Ariana Grande) relationship, where their friendship is put to test after betrayal and double crossing by the powerful figures of Oz and its political interests, Wicked for Good demonstrates that audiences all over the world are eager to defy the narratives previously imposed by the status quo.

“The most magical thing about Galinda is that she is kind of balancing her lightness and darkness quietly the whole time”, explains Ariana Grande. “And I think definitely in the second film, it gets to come to the forefront a lot more. But in the first film her light can’t exist without her darkness just underneath the surface. Her insecurities, her desperate need to have external validation, people liking her. It all has to come from somewhere”, the actress and singer told to El Heraldo de Mexico.

And while Wicked dares to explore a

Fiyero's horse is blue in Wicked: For Good, which is a subtle nod to the "horse of a different color" from The Wizard of Oz ’

darker side of The Wizard of Oz, it all relies on a much deeper study of human relationships through the fairy tale treatment. At its core, Wicked for Good is the culmination of a story embedded on learning to accept not only someone else’s differences but also our own. “I’ve always felt odd, different and even though there was an acceptance of that, I think this experience, this character and the things that have come from it have made me really fall in love with all the differences that have”, explains Erivo. “Particularly because I’ve met so many other people who have fallen in love with the difference that they have. Now feel like my difference is the thing that makes me special and that really has had a profound effect on me”, said the Academy Award nominee actress. While some stories are born to expand themselves, Wicked is one of those narratives not conformed by existing in one unique format. What started an ambiciously political tale then transformed into a generational defining musical. Now it has reincarnated into a two movie experience for an audience who doesn’t only want to see its magic but also live it. In a world saturated by shared universes sequels, reboots and multiverses, Wicked is the rare example of an original story that does not compete with its multiple adaptations but really makes them dialogue with each other. That’s a triumph.