SQUATTING THE MARVELLOUS CITY how

can squatted buildings (re)activate downtown rio?

can squatted buildings (re)activate downtown rio?

how can squatted buildings (re)activate downtown Rio?

The past six months have been a whirlwind. To write my master thesis centred on the exploration of my hometown, after years abroad, has to be the perfect ending to my studies in architecture.This work owns its success to the unwavering support and encouragement of several individuals, and it is with deep gratitude that I acknowledge their contributions.

To my family, for supporting my decision to continue my architectural education abroad and extend the duration of my studies. Their encouragement, both emotional and practical, has been indispensable to the completion of my master’s degree.

To my mother, Mônica Barbosa, for going beyond lengths to support my professional and personal growth. Despite being oceans away, her steadfast presence and belief in me have been a constant source of strength.

To my sisters, Daniela and Alessandra Orofino, whose advocacy for social justice has not only shaped my worldview, but also inspired me to ultimately make it the focus of my master thesis.

To my supervisor, Andres Lepik, for sparking my interest in a critical approach to architecture. His trust in my research and the platform he provided to explore this theme have been invaluable.

To Andjelka Gojnic, for her unwavering assistance throughout the thesis process, her patience, prompt responses, and overall support.

To Maíra Martins and Felipe Nin, for the eye-opening conversation on a rainy Wednesday evening, which particularly shaped the approach to field research on this work.

To Marcelo Edmundo, one of the national coordinators of CMP, for bridging the gap between myself and the residents of Vito Giannotti. For the enriching discussions on social equity and openness in answering my questions.

To all residents of Vito Giannotti, for warmly welcoming me into their homes and for the meaningful discussions. A special mention to Hugo Parra, who first invited me into the squat, for taking the time in sharing his insights and guiding me through the building.

To my friends in Munich, for being my home away from home (yes, kitschig, I know). A special thank you to Amelie Pretsch, Anthony Butcher, Victoria Singleton and Betina Albrecht, for their assistance, constructive criticism, and emotional support in shaping the conclusion of this master thesis.

Lastly, I am grateful to all professionals and students I have encountered over the years, who one way or another have contributed to my development as an architect.

This master thesis critically examines the potential of squatting as a transformative mechanism for reactivating downtown Rio de Janeiro. It begins with a comprehensive exploration of Centro‘s history, from its vibrant past as a cultural and economic epicentre to its subsequent decline. By analysing the socio-political forces and urban dynamics shaping the area over time, the study provides a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by marginalised communities in accessing affordable housing. It also discusses how grassroots movements advocate for housing rights amidst rising inequality. Furthermore, it evaluates the limitations and complexities of governmental housing programs, notably Minha Casa, Minha Vida, and its implementation in Rio de Janeiro. The focal point of the study is squat Vito Giannotti, which is portrayed in detail to illustrate squatting‘s transformative potential. By delving into its origins, dynamics, and community life, the thesis showcases how squatted buildings can contribute to the (re)activation of downtown Rio and promote more just and inclusive forms of urban development. Overall, this research adds empirical evidence and theoretical insights to the discourse on urban informality, housing rights, and self-governance.

Eduarda Barbosa Poubel Wissenschaftliche Arbeit zur Erlangung des Grades M.A. Architektur an der Technische Universität München

Betreuer Univ. Prof. Dr. phil. Andres Lepik

Lehrstuhl für Architekturgeschichte und kuratorische Praxis März 2024

porto maravilha & reviver centro

01 the centro of rio de janeiro 02 the “housing

social movements for housing rights & self-management housing

program minha casa, minha vida and its specificities in rio de janeiro

program minha casa, minha vida - entidades

* All presented interviews and sources originally in Portuguese have been freely translated into English by the author.

* Urban plans have used Rio de Janeiro‘s 2013 Cadastral as a reference.

1 Interview given by Marcelo Edmundo, one of the national coordinators of Central de Movimentos Populares (CMP), involved in the squatting of Vito Giannotti. Available at: Lutas Pela Moradia No Centro Da Cidade, June 28, 2018, in Is Rio de Janeiro Still Beautiful? produced by Émilie B. Guérrete, https:// youtu.be/CrddgMYjm5c?si=LAQ9MxdPLaPkuzhZ , 01:59-02:29

2 Engl.: Brazilian Social Security Institut.

3 Engl.: Celebration Day.

4 A nationwide platform for popular and trade union‘s communication.

Fig. 1: Picture by Pablo Vergara. Available at: Pablo Vergara, “Ocupaciones verticales: sobrevivir en la región portuaria de Río de Janeiro“, El País, April 29, 2023, https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/2023-04-30/ocupaciones-verticales-sobrevivir-en-la-region-portuariade-rio-de-janeiro.html#?prm=copy_link (last accessed on March 6, 2024)

“Despite all the attacks we have been suffering, (…) the people of the region keep resisting. They have resisted since the slave ships, in favelas and cortiços, through samba and capoeira, they keep resisting in squats. It is our only way to preserve our history in this region. If we don’t resist, we die. While we struggle, we live in the hope of changing things.“1

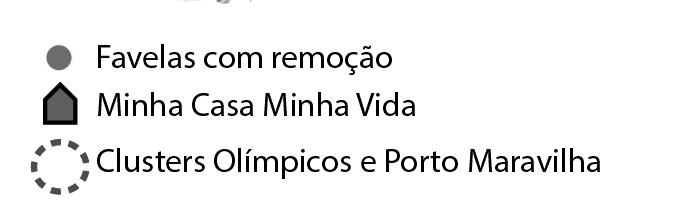

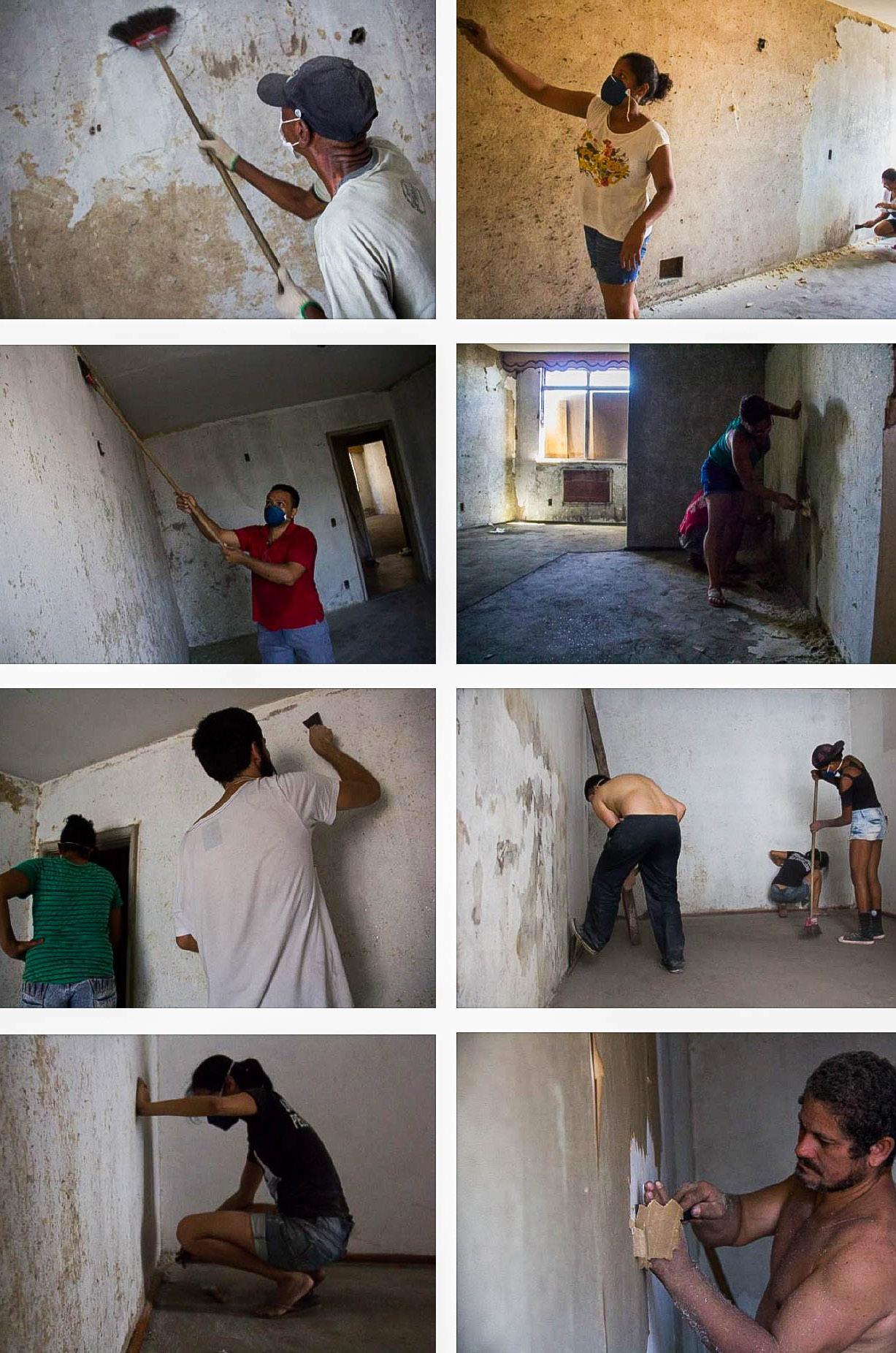

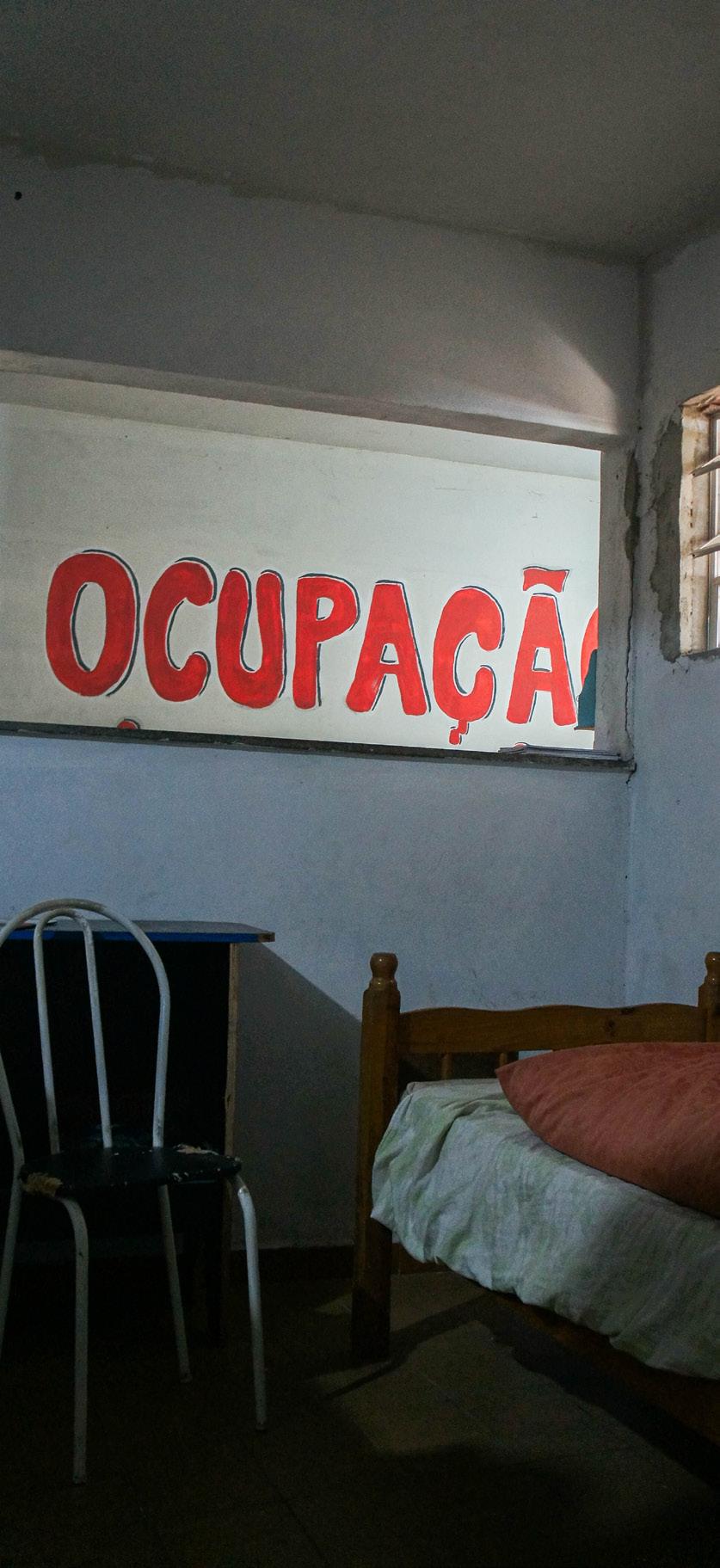

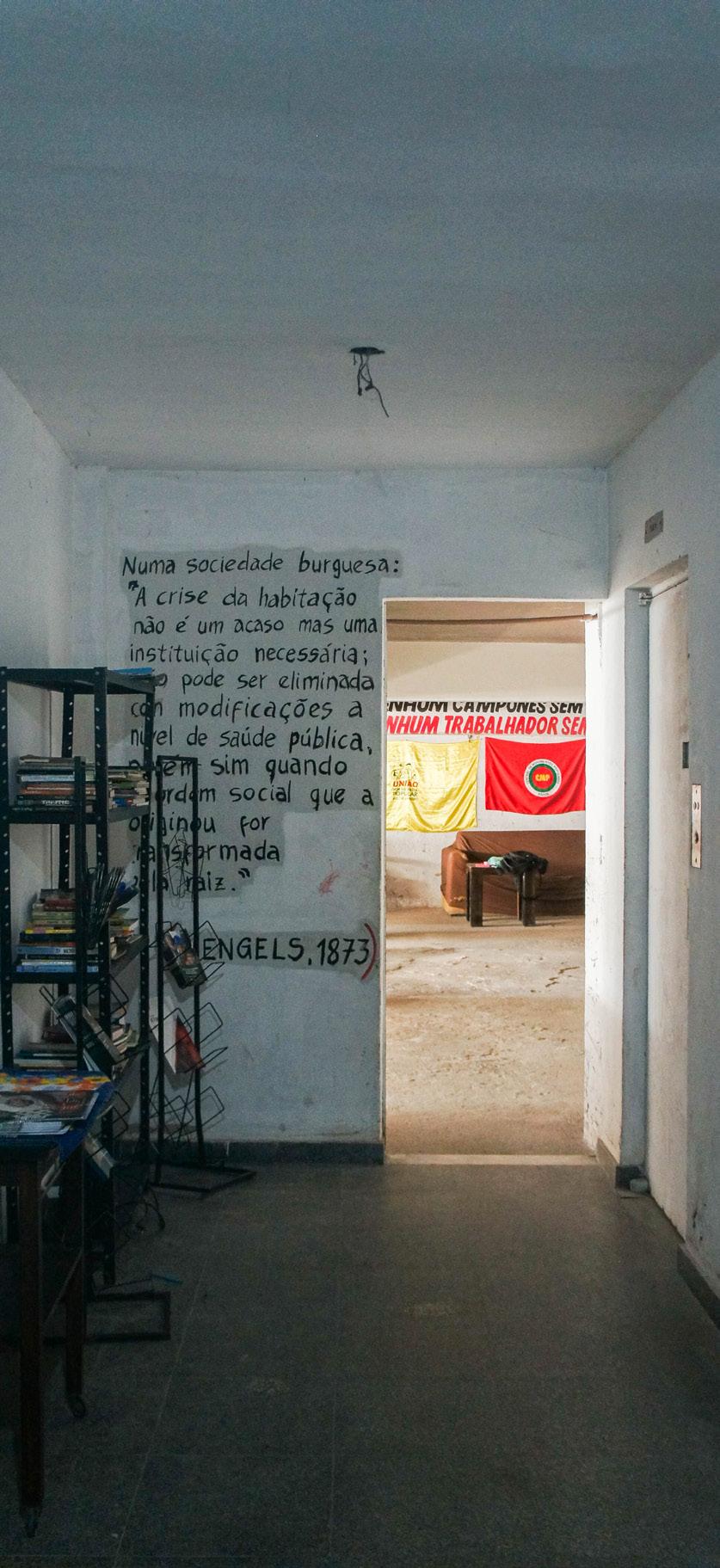

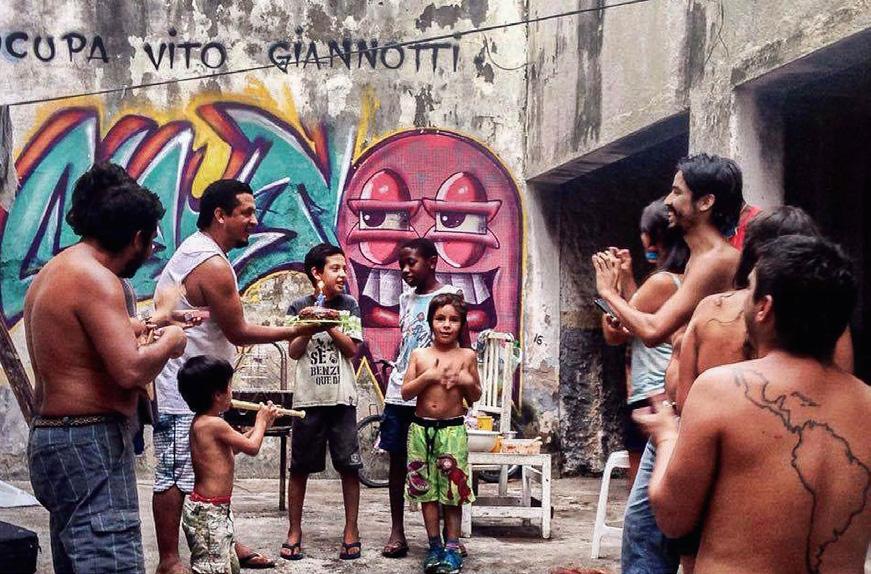

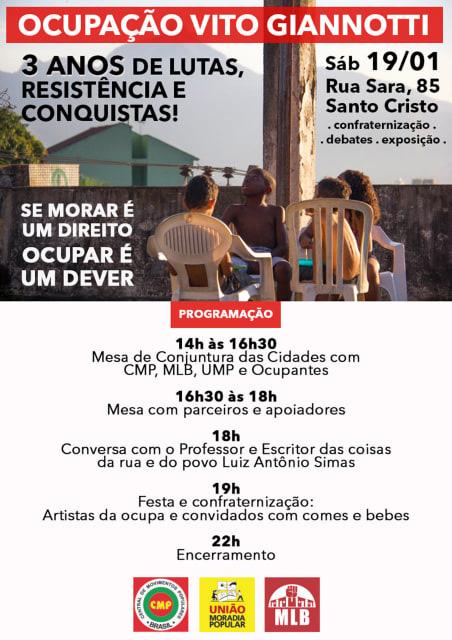

In the early hours of January 15th, 2016, squatters gathered in the Novo Rio Bus Terminal, less than one kilometre away from their final destination. After being divided into smaller groups, they were guided to Rua Sara 85, a street in Morro do Pinto, in the neighbourhood of Santo Cristo, Rio de Janeiro. The building, previously a hotel and then property of Instituto Nacional de Seguro Social2 (INSS), had been vacant since the 1990s, and was entered with little resistance, marking officially the squat’s Dia de Festa3 - given name to the date of occupation of an abandoned building.

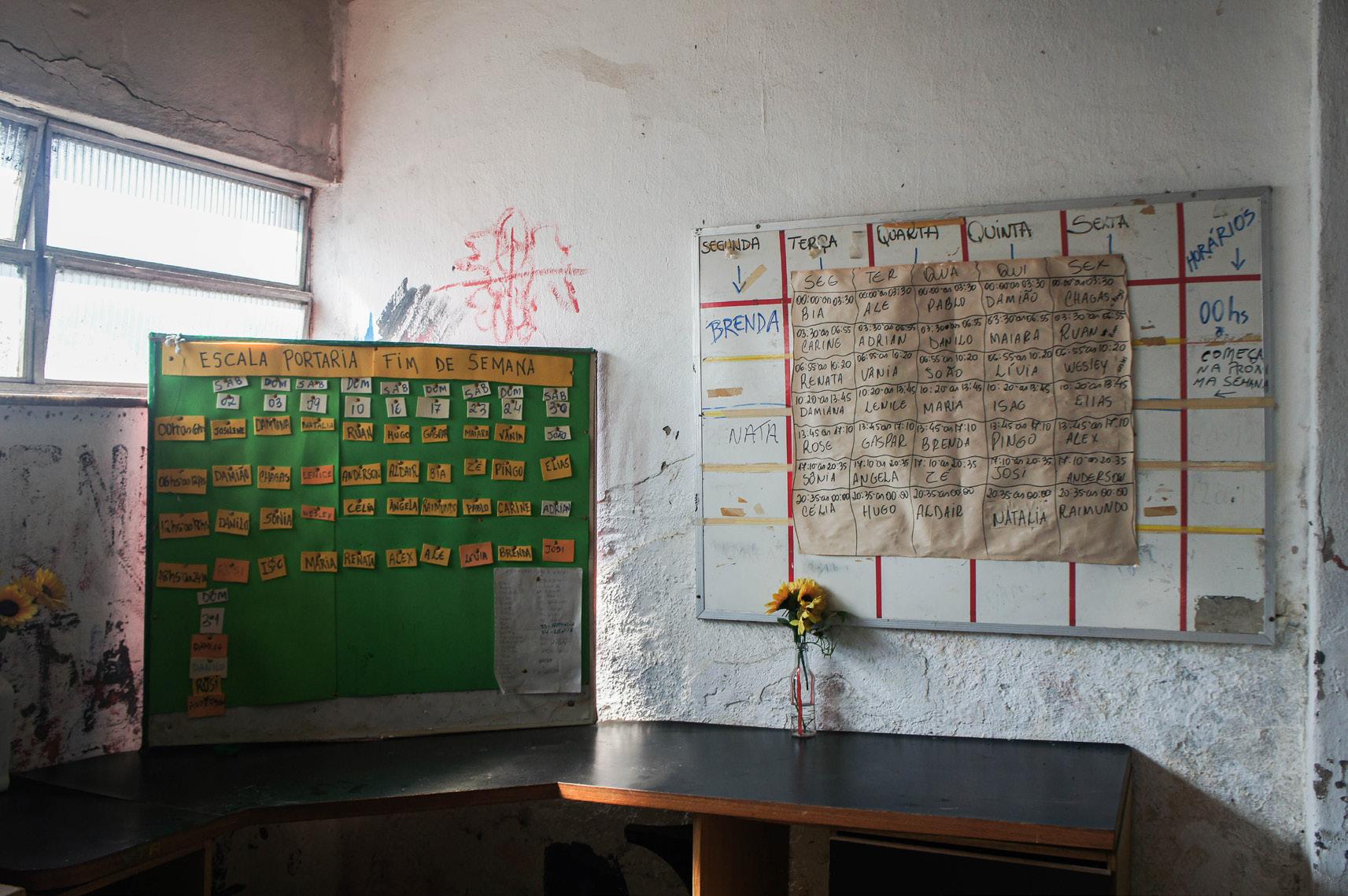

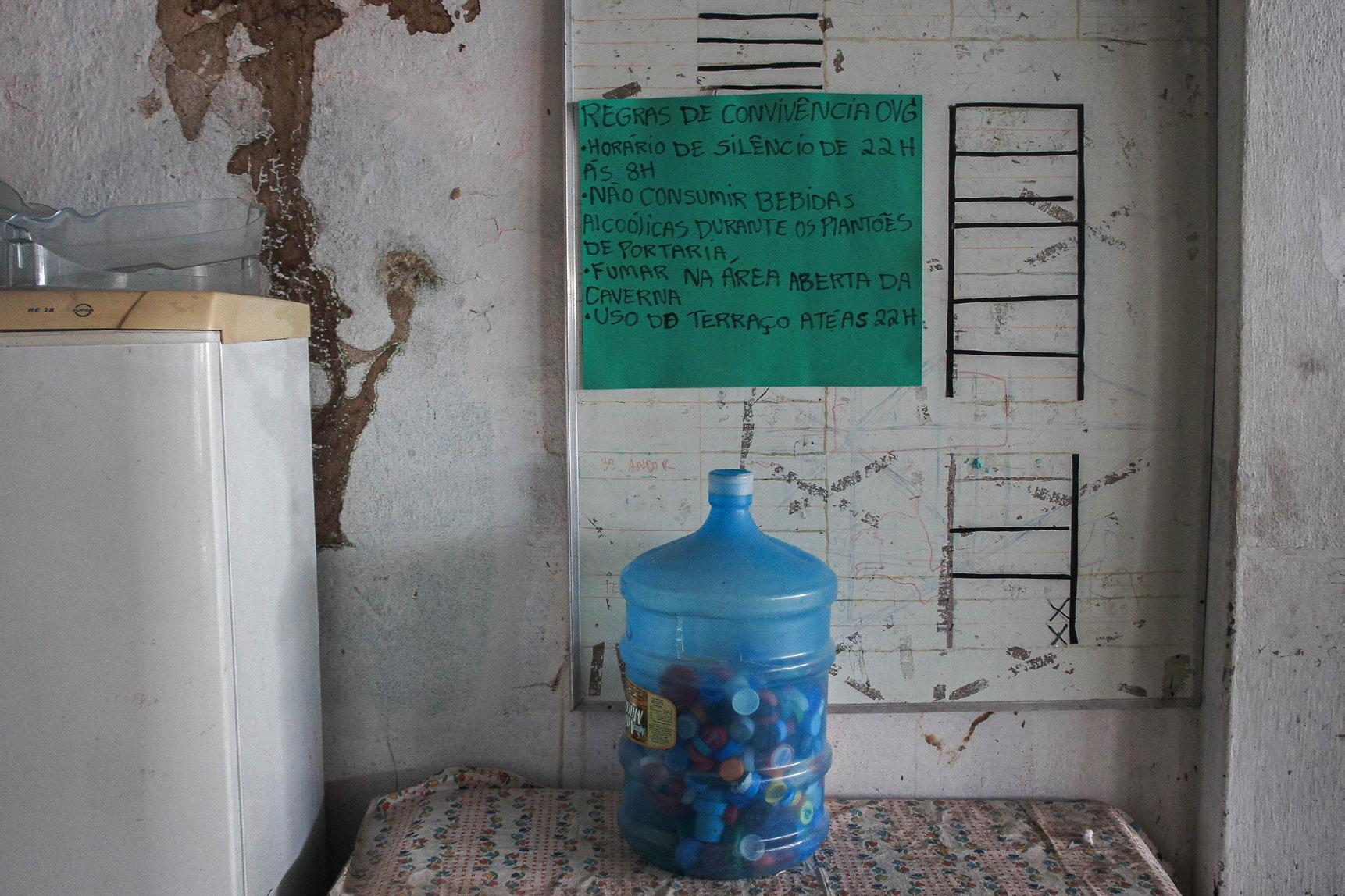

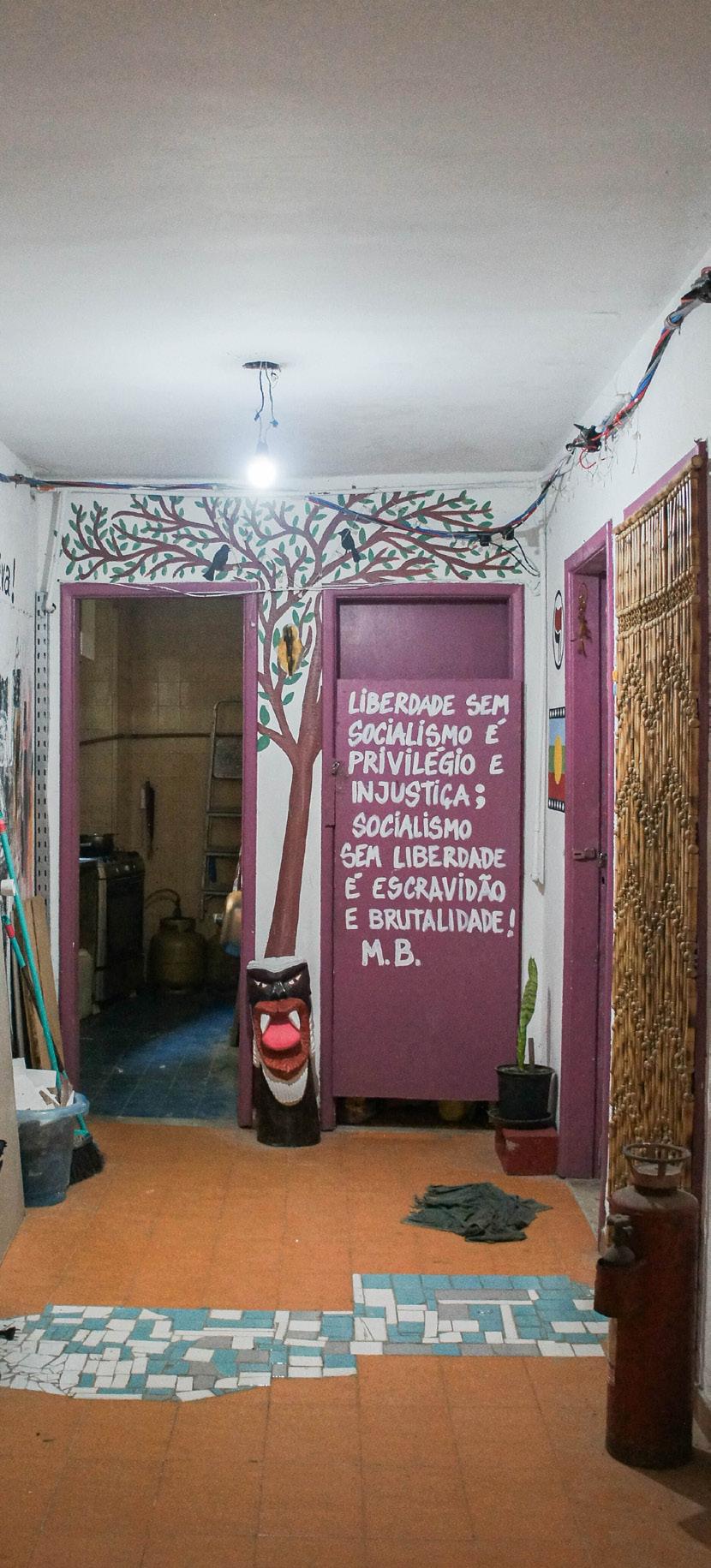

A decade earlier, it was decided the edification should be destined for social housing purposes by decree INSS/PRES nº21, de 16 de Agosto de 2006, yet it remained empty. This inertia prompted three distinct social movements - Central de Movimentos Populares (CMP), União por Moradia Popular (UMP) and Movimento de Lutas nos Bairros, Vilas e Favelas (MLB) - to unite forces. Their collective goal: to pressure the government into fulfilling the resolution and ultimately plan the building’s occupation. The newly formed squat received the name Vito Giannotti (OVG), in homage to the Italian immigrant, worker and educator of the same name, founder of Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação4 (NPC), who would have celebrated his 73rd birthday on the same day as the building’s occupation. By naming the building after an important personality of the worker’s movement, attention is drawn to the resistance of historically marginalised groups in (re)occupying the central area of Rio de Janeiro. Simultaneously, it addresses the region’s high vacancy and tackles the housing crisis in Brazil. Fast forward to the present day, and the old hotel has become home to 28 families from diverse social backgrounds, collectively managing

the building and, through mutual care, seeking for its long-term functionality.

In 2006, American journalist Robert Neuwirth published the book Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World, shedding light on urban squats worldwide. Drawing from a two-year immersive research experience living in squatted communities across various metropolises, Neuwirth offers profound insights into the resourcefulness and organisational levels of these communities. He argues that informal settlements are an integral part of urbanisation and cannot be disregarded. Neuwirth captures the essence of squatting succinctly, stating

“They are excluded so they take (..) but they are not seizing an abstract right, they are taking an actual place: a place to lay their heads. This act - to challenge society’s denial of a place by taking one of your own - is an assertion of being in a world that routinely denies people the dignity and validity to inherent in a home.”5

While the act of squatting abandoned or unoccupied land has always existed, as argues author Colin Ward6, organised forms of occupation, meaning supported or inspired by social movements, is a relatively newer phenomenon. In The Autonomous City, Alexander Vasudevan (2017) reconstructs the history of “organised squatting” across European and North American cities, with first stories dating back to the 1960s. Vasudevan highlights the movement’s significance in shaping urban spaces and questioning the capitalist logic of housing as a commodity.

“Housing is no longer seen as a basic social need. It has become an instrument of profit-making transforming today’s cities into sites of intense displacement and inequality, exploitation, and poverty.”7

While Europe was witnessing emancipatory movement in cities such as Amsterdam London and Berlin, Brazil lived under military dictatorship until 1985. Populations in cities such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo were skyrocketing, and insufficient housing policies and high rent costs drove the country into a massive housing crisis. With nowhere to go, processes of occupation on the fringes and slopes of cities intensified, forming new entire neighbourhoods made from informal settlements - the favelas8

5 Robert Neuwirth, Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World (New York, London: Routledge, 2016), chap. 10, https://www.perlego.com/ book/2192784/shadow-cities-a-billionsquatters-a-new-urban-world

6 “Squatting is the oldest mode of tenure in the world, and we are all descended from squatters. This is as true of the Queen with her 176,000 acres (710 km2) as it is of the 54 percent of householders in Britain who are owner-occupiers. They are all the ultimate recipients of stolen land, for to regard our planet as a commodity offends every conceivable principle of natural rights.“ Colin Ward, “The early squatters”, in Squatting: The Real Story, ed. Nick Wates and Christian Wolmar (London: Bay Leaf Books, 1980), 104

7 Alexander Vaseduvan, The Autonomous City (New York, London: Verso, 2017), Introduction, https:// www.perlego.com/book/731022/theautonomous-city-a-history-of-urbansquatting

8 The Brazilian Portuguese word favela is used to describe slums. Its origin lies on the name of Brazil‘s first slum, named Morro da Favela, known today as Morro da Providencia, in the harbour region of Rio de Janeiro. While favelas have been an urban phenomenon since the early twentieth century, they rapidly multiplied with Brazil’s industrialization process and population growth, especially during the second half of the century.

9 Engl.: Dream of homeownership.

10 Marcelo Edmundo, E-Mail to student, 2007.

11 David Harvey, “The Right to the City“, New Left Review 53, Sep-Oct 2008, 23.

In response, organised squats emerged in São Paulo in the beginning of the 1980s, initially focused on producing new housing units, inspired by Uruguay‘s self-management housing project - the Cooperativas de Vivivenda por Ayuda Mutua. However, they swiftly shifted their focus to abandoned buildings, due to high vacancy rates in central areas. Unlike their European counterparts, the Brazilian squatting movement primarily originated from the urgent need for housing and later evolved into a progressive agenda. Additionally, it is closely intertwined with the Brazilian „sonho da casa própria”9, a deeply ingrained cultural aspiration in Brazil, where owning a home is often seen as a significant life achievement and a symbol of stability and success.

“The house has a very strong symbolism: if we have an address, we are someone, and if we are someone, we have rights, and if we have rights, we can and should demand them, and that‘s where the danger lies for the eyes of the ‘powerful’.“10

Moreover, the Brazilian squatting movement is intrinsically linked to the country’s history of slavery and colonialism, which forcibly displaced black and indigenous populations from their homes. In this sense, more than a housing movement, they collectively reclaim their agency in shaping an urban landscape built upon exclusion, embodying David Harvey’s right to the city.

“It (the right to the city) is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization.”11

Rio de Janeiro, hailed throughout history as the “marvellous city”, the “Paris of the tropics”, the “Olympic city”, presents a paradoxical reality: a city that strove to mirror the project of a modern, europeanised Brazil; at the same time, a city shaped by inequality, where a quarter of its population lives in favelas, and its city centre prevails under a narrative of urban decay How could a growing city continuously have its central area decrease in population? How did the heart of the once country’s capital “fail into oblivion”? Surely there have been several attempts to revitalise, refurbish, renew, reactivate the region: but all sidelining lower-income populations in favour of corporate and commercial interests, exacerbating social inequalities. In light of

these failed urban strategies, the question arises: could urban squats offer a viable alternative in reactivating Rio‘s downtown area?

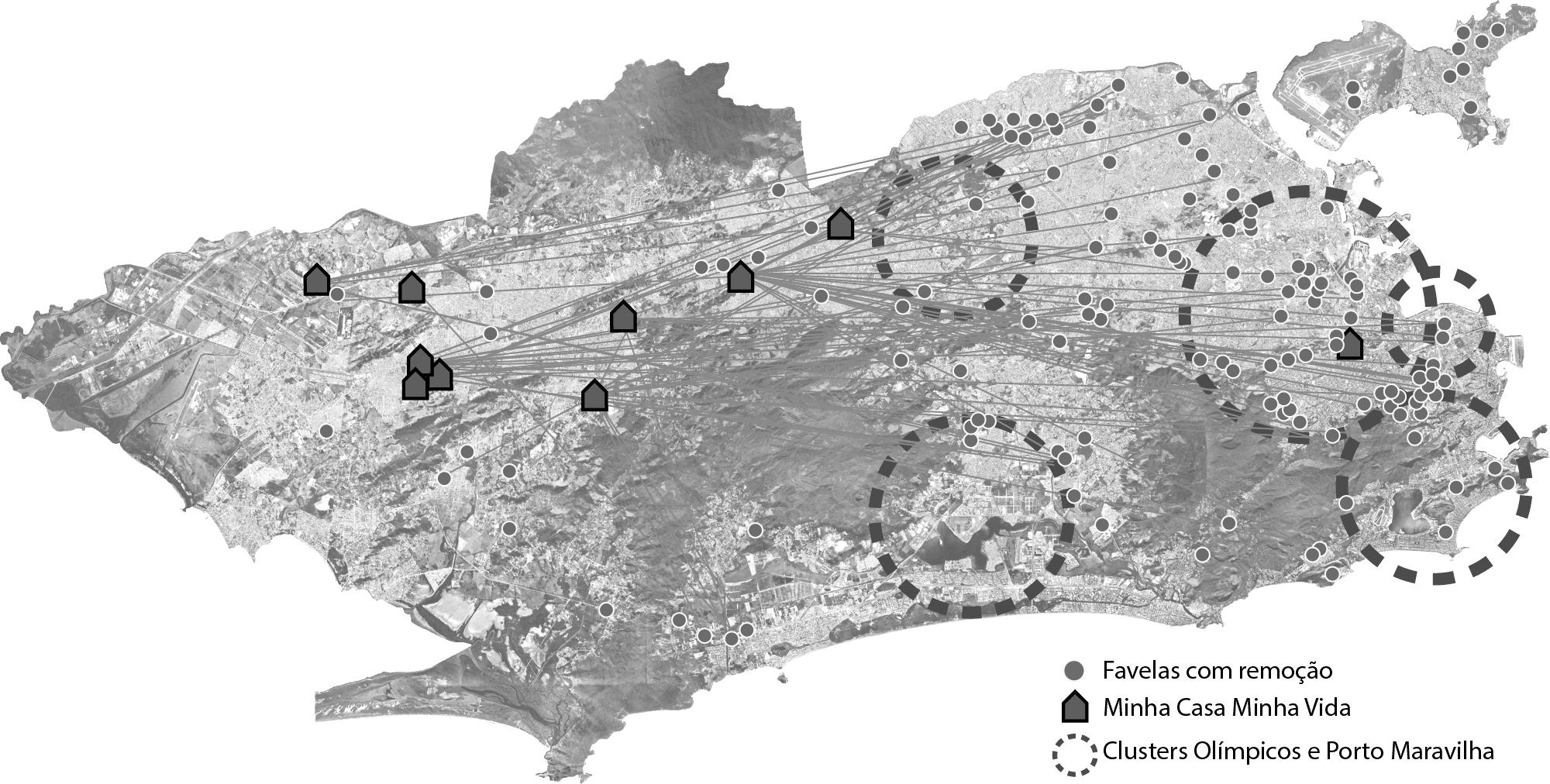

The choice to analyse the impacts of squatted buildings in this region is deeply personal. Growing up in Rio de Janeiro, I have witnessed first-hand the glaring disparities in the citythe result of high inequality and segregation. These disparities have prompted my desire to understand and address urban challenges faced by marginalised communities, often relegated to precarious living conditions on the city‘s periphery. Moreover, the repeated pledges from politicians to revitalise downtown Rio, including initiatives like Porto Maravilha, have piqued my curiosity regarding the efficacy of such urban redevelopment efforts. With the forced evictions leading up to the Olympic Games, which displaced several squatting communities in the downtown area, I have come to develope a deep admiration for squatters and their organising entities. By reclaiming a space historically denied to marginalised communities, squatters offer a bottom-up alternative for addressing housing challenges and urban redevelopment, one that prioritises community empowerment and inclusivity.

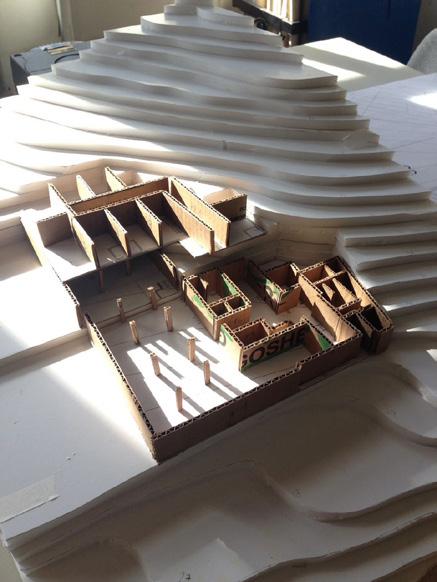

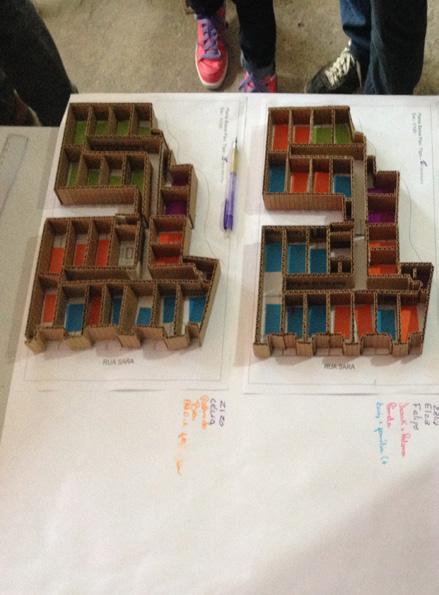

As we dive into the text, the subsequent chapters will unfold in two parts. The initial chapters will draw upon existing literature to delve into the background of urban squatting in Rio de Janeiro. The first chapter will focus on understanding the downtown area, exploring its borders, significance to the black movement, and current urban plans. The subsequent chapter will focus on the housing crisis in Brazil, touching upon the notion of “housing apartheid“ and the responses of housing rights movements, culminating in an examination of the nationwide housing policy, Programa Minha Casa, Minha Vida (PMCMV), initiated by President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva12 in 2009. The second part of this study will serve as an intermezzo: moving away from written sources of knowledge to focus on a case study, Vito Giannotti. Drawing from three months of field research conducted in Brazil between November 2023 and February 2024, this chapter will unfold around visuals, including photographs, floor plans, and oral interviews. Through these first-hand accounts, the story of the squat will be retold by the very individuals who made it happen.

12 Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or Lula, is a Brazilian politician and one of the founders of Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) (engl.: Worker’s Party). He has been President of Brazil between 20032011 and was once again re-elected, in 2023. While his governance has been met with great polarisation among the Brazilian population, he remains one of the most influential politicians in the country.

Fig. 2 (next page): Picture by Pablo Vergara. Available at: Pablo Vergara, “Ocupaciones verticales: sobrevivir en la región portuaria de Río de Janeiro“, El País, April 29, 2023, https://elpais. com/planeta-futuro/2023-04-30/ ocupaciones-verticales-sobrevivir-enla-region-portuaria-de-rio-de-janeiro. html#?prm=copy_link (last accessed on March 6, 2024)

Squat Vito Giannotti stands as just one example amidst numerous squats dotting the central area of Rio de Janeiro. As a prominent emblem of organisation and accomplishment, it serves as an ideal showcase for the potential role of squats in redefining the downtown region of the city, with the same people and stories historically denied this space.

“Cidade maravilhosa

Cheia de encantos mil Cidade maravilhosa

Coração do meu Brasil”13

The history of Rio de Janeiro begins in 150214, when the initial contact between the Portuguese and the indigenous peoples inhabiting the region took place. However, because the area was not originally perceived as strategic by the Portuguese, mainly due to their interest in Brazilwood – which was scarce in the region, the city was only founded in 1565. Rio’s topography, nestled between the mountains and the sea, made it ideal for the establishment of a fortified centre and harbour, which contributed to the city’s rapid growth as a colonial port city and to its pivotal role in securing control over the colony. Moving swiftly into becoming the main point of slave trade in colonial Brazil, to being capital of Portugal’s empire and subsequent the capital of an independent Brazil, Rio de Janeiro was the beating heart of the country, bearing witness to its evolution through a palimpsest of architectural styles15. From colonial townhouses to belle-époque landmarks, and from Modernist high-rises to contemporary structures, the cityscape reflects the many phases of Brazil throughout history. However, Rio’s hegemony began to fade in the twentieth century, catalysed by the transfer of the capital to Brasília, in the 1960s. This shift marked a turning point in Rio’s trajectory, as its national importance diminished. Today,

“Rio’s city centre configurates a place of dispute, cyclically undergoing periods of investment, degradation (from the elite’s perspective) and renovation, when those interested in profiting from the (re)production of space emerge.”16

13 Engl.: Marvellous city / Full of a thousand charms / Marvellous city / Heart of my Brazil. Originally written in 1934, by Antonio André de Sá Filho, the song quick became one of the most popular carnival marches in Rio. In 1960, it was adopted as the city’s official anthem, being recognized by the local government in 2003, by Lei 3.611 de 12 de Agosto de 2003 O Globo, “’Cidade Maravilhosa’: Expressão que deu Nome ao Hino Carioca tem Origem Misteriosa”, March 1, 2021, https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/ cidade-maravilhosa-expressao-quedeu-nome-ao-hino-carioca-tem-origemmisteriosa-24904185.

14 Here I refer to the history of Rio as a city, as the area had been previously occupied by tupinambas, indigenous people that inhabited Brazil’s coast before the arrival of the Portuguese.

15 Irene de Queiroz Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias De Uma Ocupação No Centro Do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital, 2015), 59.

16 Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 44.

Fig. 3: Picture by Leando Ciuffo, September 8, 2012. Available at: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/ leandrociuffo/7958684150/in/set72157624814401801 (last accessed on March 6, 2024)

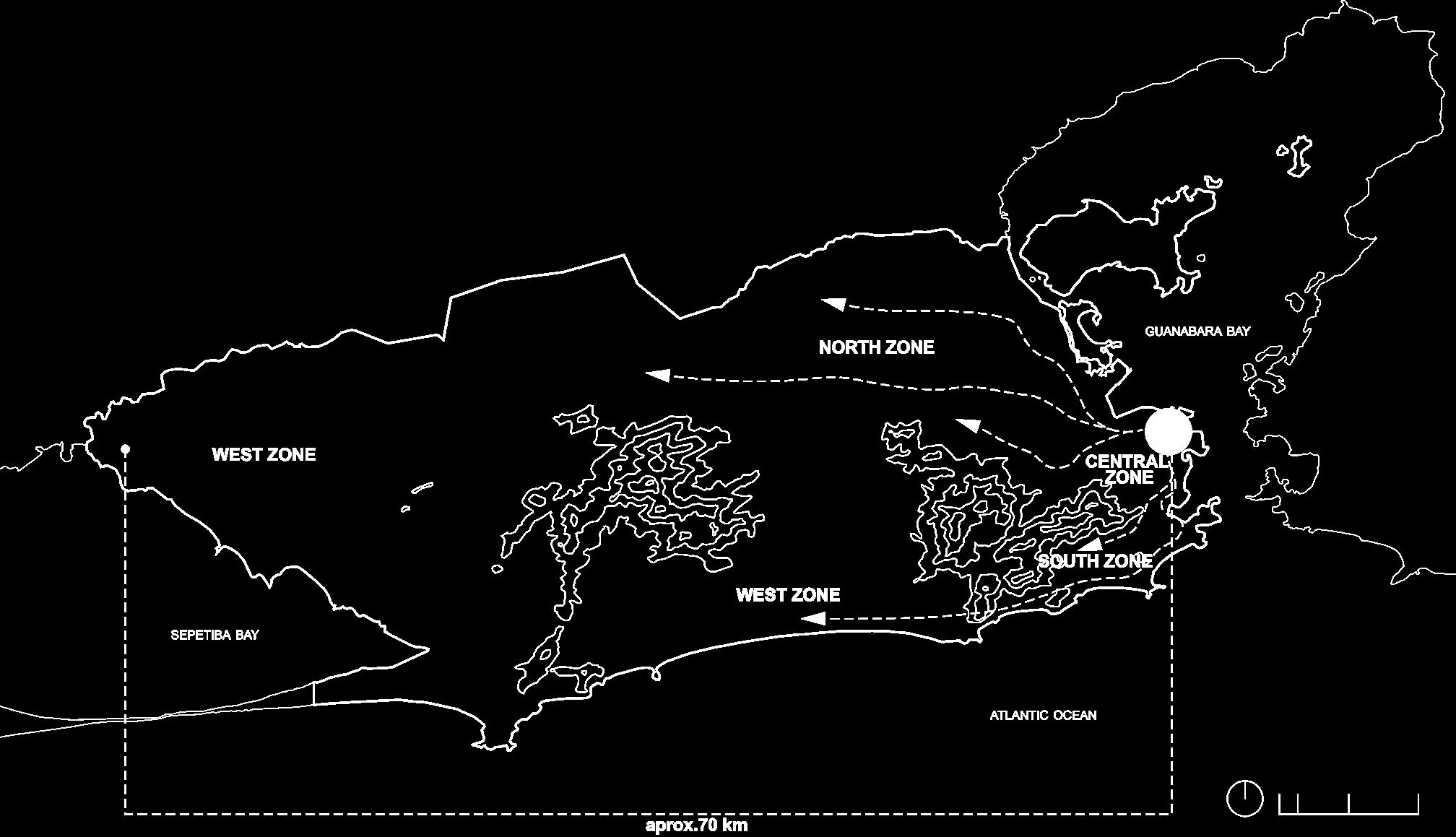

Due to its peculiar topography, characterised by mountains that cut through the city, Rio de Janeiro’s urbanisation process has followed a unique trajectory. Unlike cities like Munich or São Paulo, which experienced radial urban expansion, Rio’ growth has been predominantly linear. The city began its development along the shores of Baía de Guanabara17, developing into two major stripes – south and north of the Tijuca Massif, which also encompasses the Tijuca National Park18. Consequently, Rio’s historic city centre finds itself somewhat displaced within the city’s geography, situated in the southeast part of the metropolis, where the first harbour was constructed. As a result, considerable distances of up to 70 kilometres can separate the newly developed neighbourhoods in the west from the city centre in the east.

17 Engl.: Guanabara Bay.

18 “One of the largest urban forests in the world, was established in 1861 by Emperor Pedro II to reforest the area affected by deforestation caused by sugarcane and coffee cultivation.“ Riotur, “Tijuca Florest”,https://riotur.rio/ en/que_fazer/tijucaforest/.

Fig. 4: The urban development of Rio de Janeiro. Drawing by author.

Urban development of Rio de Janeiro and the 4 zones of the city (topography lines every 200 meters).

19 “Pertaining to the city of Rio de Janeiro, capital of the state of Rio de Janeiro, or a native or inhabitant thereof. Origin: ETIM (1560) tupi kari‘oka, prov. from tupi kara‘ïwa ‚white man‘ + ‚oka ‚house‘” Oxford Languages, s.v. “carioca”, accessed March 10, 2024, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/ carioca_n?tl=true.

Fig. 5: Rio de Janeiro‘s planning areas. Drawing by author.

Fig. 6: Rio de Janeiro‘s AP1.Drawing by author.

Fig. 7 (next page): Figure plan of the referred neighbourhoods. Drawing by author.

The city’s administrative structure is organised into five primary Planning Areas (APs), further subdivided into Administrative Regions (R.A.), and neighbourhoods. The central area of the city corresponds to the first Planning Area (AP1) and is divided into administrative Regions I, II, III, VII, XXI and XXIII. Although only the R.A. II bears the name of Centro, this title is used by the cariocas19 to refer to a broader area, partially expanding into the R.A. I (Portuária). For this reason, the title Centro will be used herein to encompass the neighbourhoods of Gamboa, Saúde, Santo Cristo, Centro, and Lapa, transcending conventional administrative nomenclatures.

SAÚDE

plan of the referred neighbourhoods:

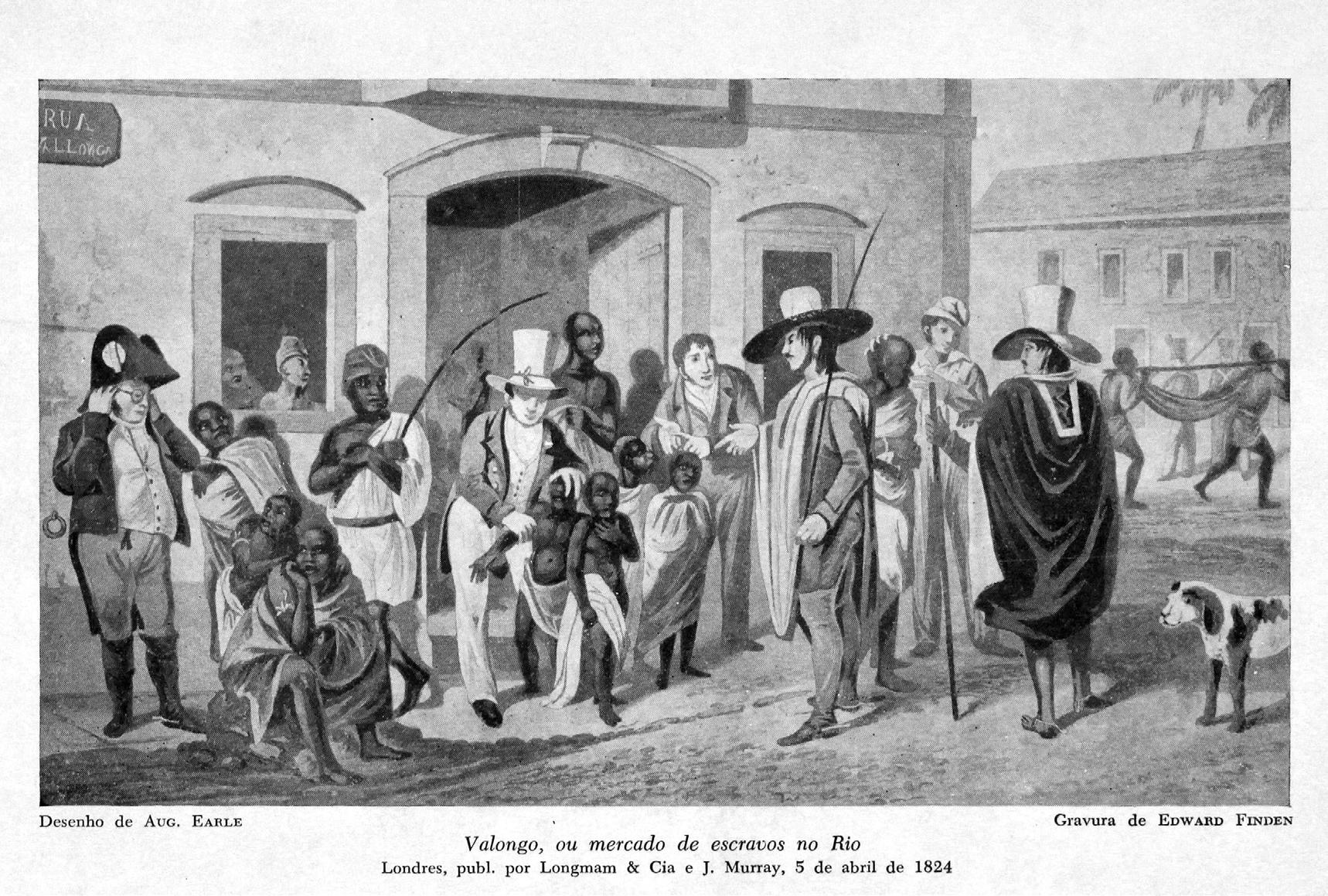

The central area holds significant historical importance in the development of Rio de Janeiro, tracing back to the city’s foundation in 1565. It was here that Portuguese colonisers first settled in the region, establishing a vital hub for the export of Brazilian goods, particularly sugar, which were shipped off to Portugal, while import materials, especially that from labour coming from African colonies, arrived. Although some sugar plantations were to be found in the adjacent areas to Rio, they were mostly located around Salvador20, in the northeast. It was only in the eighteenth century, with the discovery of gold in today’s equivalent area to Minas Gerais21, that Rio saw its economy flourish and became the hub for the export of gold and other minerals. This newfound wealth elevated Rio to capital of the colony, in 1753, prompting the construction of new buildings and infrastructure. Amidst Brazil’s golden age, workforce’s demands also increased, intensifying slave trade activities. Appalled by the sight of enslaved Africans in the city‘s political, economic, and religious centre, the local elite urged the government into relocating the commerce to a different area.

“The parade of half-naked, squalid and pestilential blacks in the political, economic, administrative and religious centre of the city, which had Paço dos ViceReis (today, Praça XV) as its epicentre, certainly brought embarrassment and fear to the elites, who were afraid of being contaminated by their diseases. Because of this, they had to be relocated far away, to a place with less exposure and visibility, where they wouldn‘t pose a threat or cause so much discomfort.”22

Thus, in 1774, Cais do Valongo is born - a wharf set apart from Rio’s urban core, in today’s equivalent neighbourhood of Gamboa. Surrounding the wharf, new constructions emerged to support the commercial activity, such as Cemitério dos Pretos Novos23 and Largo do Depósito24, shaping the region into a hub for slave trade activities. Here, an estimated one million African slaves arrived25 until its deactivation in 183126, marking Cais do Valongo as the largest gateway for forced black labour in the Americas27. Yet, even after its closure, the area continued to be occupied by freed slaves, who kept on working and living in the region, forging a community known as Pequena África28 - an enclave of Afro-Brazilian culture. It was also here, where Brazil’s first favela, Morro da Providência, took root, with first settlements dating from 1897.

20 Brazil‘s first capital, located in the state of Bahia, in the northeast region.

21 Neighbouring state to Rio de Janeiro, also in the southeast region of the country.

22 Tânia Andrade Lima et. al “Em Busca Do Cais Do Valongo, Rio De Janeiro, Século XIX”. Anais Do Museu Paulista: Estudos De Cultura Material 24 (January-April 2016), n.pag.

23 Burial place for those who did not survive the crossing and died on their way to Brazil.

24 Place where slaves were brought to gain weight, before being taken back to Valongo, to be sold to the local elite.

25 Slave Voyages, Transatlantic Database, accessed on March 5, 2024, https://www.slavevoyages.org.

26 Consequence of the prohibition of slave trade across the Atlantic, in 1831. The activity continued in illegal harbours.

27 Research conducted by the University of Emory, in Atlanta, USA, estimates that roughly 4.8 million slaves arrived in Brazil. This number is much higher than the original 3.6 million estimative by Maurício Goulart, published in his book African slavery in Brazil, in 1949. Another fact that draws attention is 2.5 million arrivals in southeastern Brazil alone, with 90% being in Rio. Available at: Slave Voyages, Transatlantic Database, accessed on March 5, 2024, https://www.slavevoyages.org.

28 Engl.: Little África

Fig. 8: “Valongo ou Mercado de Escravos no Rio“, drawing by Augustus Earle, etching by Edward Finden, April 5, 1824. Available at: Wikipedia, https:// pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ficheiro:Augustus_ Earle_-_Rua_do_Valongo.jpg (last accessed on March 5, 2024).

29 Settlements founded by African runway slaves who escaped and resisted the regime. Today, quilombos still exist in Brazil as a place ethnic, political and cultural resistance.

Fig. 9: The transfer of harbour activities. Drawing by author.

Fig. 10: Afoxé group Filhos de Gandhi at Pedra do Sal. Picture by unknown. Available at: Rio Antigo (@ rioantigo), Instagram, November 20, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/ B5GcRrxHGp0/?epik=dj0yJnU9dHVEa3FzSjc2c3BXbjNjQ2lINTNXemlCdjRZZndzdkkmcD0wJm49UnVOVjVXT051a0tmb2lmcE5sWnpXUSZ0PUFBQUFBR1huaFJj

Fig. 11 (next page): Casa da Tia Ciata, at Rua Visconde de Itaúna 119. The house served as refugee for many samba composers in the beginning of the twentieth century, but was eventually demolished. Today, Casa da Tia Ciata gives name to a cultural centre to honour her name, also in the Pequena África. Picture by Augusto Malta. Available at: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

Fig. 13 & 14 (p.32): First esvacations for the Cais do Valongo, 2011. Picture by: Tânia Lima Andrade et al. Available at: Andrade et al, “Em busca do Cais do Valongo“, n. pag. (last accessed on March 5, 2024).

Fig. 15 (p.33): Cais do Valongo after escavation. Picture by unknown. Available at: Maria Monteiro, „Cais do Valongo, principal porto de entrada de escravos no Brasil, classificado pela UNESCO“, Público, July 10, 2017, https://www.publico.pt/2017/07/10/ culturaipsilon/noticia/cais-do-valongoprincipal-porto-de-entrada-de-escravos-no-brasil-classificado-pela-unesco-1778558 (last accessed March 5, 2024)

However, a mere twelve years after its deactivation, Cais do Valongo was covered to make way for Cais da Imperatriz, a new harbour constructed to receive Princess Teresa Cristina, wife of Brazil’s at-the-time Emperor, Dom Pedro II. Several decades later, the structure faced yet another layer of transformation. This time, it was covered as part of Pereira Passos’ ambitious urban renewal efforts, which expanded the harbour area towards Baía de Guanabara through the creation of artificial embankments. It was only in 2011 that construction crews discovered the ruins of Cais do Valongo, under preparation works for the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. The double layering of this historical wharf carries with itself profound symbolism, representing the ongoing erasure of black communities in this region, who, from the beginning of the twentieth century, also suffered with diverse evictions policies, justified by the hygienist and modernist movements. In this sense, the Pequena África emerged as a symbol of resistance. While the population residing in this area has dwindled over time, landmarks such as quilombo29 Pedra do Sal and Casa da Tia Ciata continue to be cherished and frequented by Rio’s African Diaspora population, serving as reminders of their heritage and resistance in the region.

Left: Transfer of slave-trade activities from Praça XV to Cais do Valongo, in 1774.

Highlighted, the area known as Pequena África.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Brazil found itself amidst great transformation, its cities experiencing a significant population surge. Following the abolition of slavery in 1888, and the influx of new working-force coming from Europe, lower-income groups gathered in overcrowded tenement houses, known as cortiços - typical housing typology during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike European tenement houses, they were usually established in already existing structures, mainly bourgeois houses that were later subdivided into small apartments. In parallel to the housing crisis, Rio de Janeiro grappled with rampant epidemics, including yellow fever and tuberculosis, largely attributed to unsanitary living conditions and rapid population growth. Both housing and sanitary crises unfolded almost in tandem, with the central are as its epicentre, where disordely and dense cohabitation proliferated on an increasingly large scale 30 .

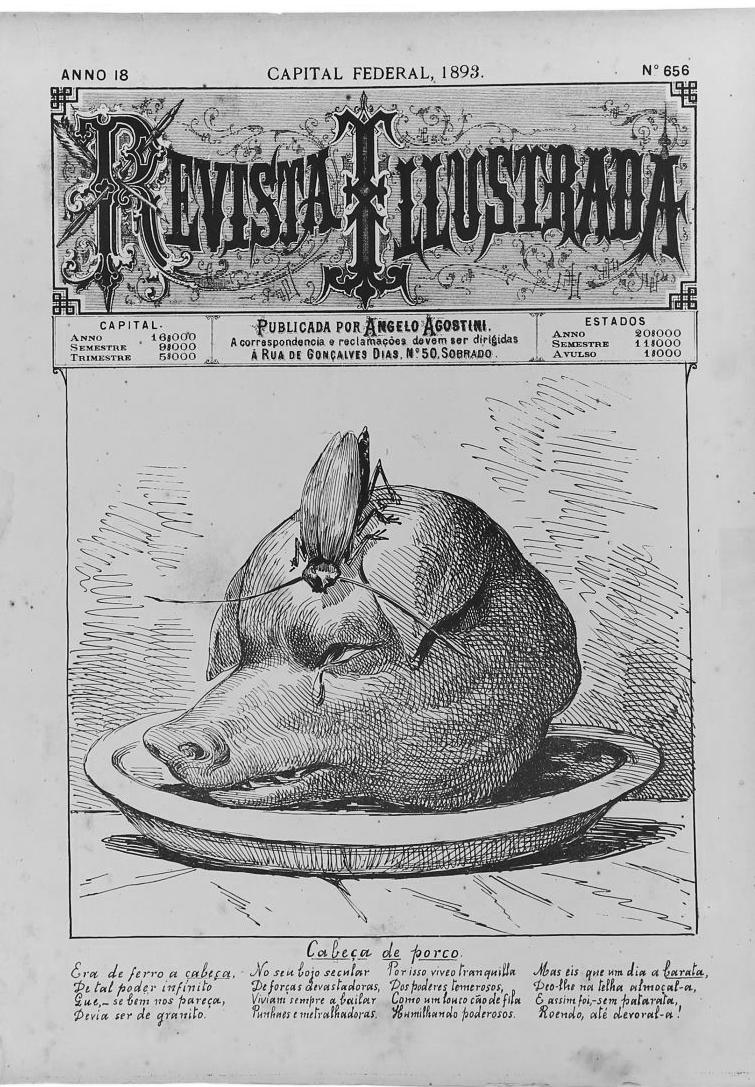

In response, cortiços were singled out as hotbeds for disease transmission and were gradually demolished. Among the most remarkable episodes during this period is the implosion of Cabeça de Porco31, a cortiço in Rio’s harbour region, with approximately 2 thousand inhabitants32. Its demolition in 1893, marked the beginning of a series of evictions, forcing displaced residents to seek housing in the city’s outskirts. It also initiated a series of urban reforms, such as the expansion of the city to other areas, norms for the construction of hygienic houses, opening of big avenues and squares, forestation, among others33

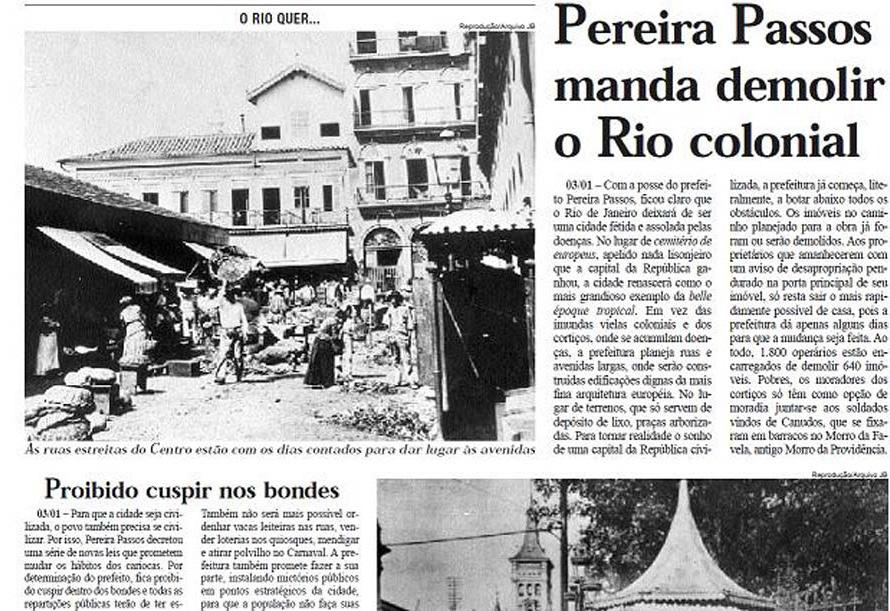

The turn of the century was marked by an even more accelerated population growth, and Rio de Janeiro struggled to find its place among other international capitals. With the country’s economic growth and presence in the international market, there was a need for a modernised capital, one that symbolised the “new Brazil”34. This, coupled with the still recurring epidemics in the city and concerns over public health, culminated in Pereira Passos’ Urban Reform, in 1903.

“(…) the city‘s growing importance in the international context did not fit in with the existence of a central area that still had colonial characteristics, with narrow and shady streets, and where the seats of political and economic power were mixed with carts, animals and cortiços.”35

30 Jaime Larry Benchimol, Pereira Passos: Um Haussmann Tropical - A Renovação Urbana da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro no Início do Século XX (Rio de Janeiro: Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, Turismo e Esportes, 1992), 124.

31 Engl.: Pig‘s head.

32 Cabeca de Porco”, Rio Memórias, https://riomemorias.com.br/memoria/ cabeca-de-porco/.

33 Benchimol, Pereira Passos: Um Haussmann Tropical, 117.

34 Maurício A. Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro: Publicações Pereira Passos, 2022), 81.

Fig. 16: : Cover of Revista Illustrada (local newspaper) announcing the demolition of cortiço Cabeça de Porco, in 1893. Available at: Revista Ilustrada, n 656, February, 1893 quoted in Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, 68.

Fig. 17: Charge of Oswaldo Cruz cleaning-up the Morro da Favela,.” Available at: O Malho n 247, June 8, 1907, https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:Oswaldo_Cruz_passa_o_ pente_fino_da_“Delegacia_da_ Hygiene%22_no_Morro_da_Favela.jpg (last accessed on March 3, 2024).

35 Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, 81.

Announcement of Cabeça de Porco‘s demolition at the local lewspaper “Revista Illustratada“, in 1893.

Charge of Oswaldo Cruz cleaning up the Morro da Favela.

“An indispensable cleanup. Hygiene is going to clean up Morro da Favela, next to the Central Railway. To do so, it has ordered residents to move out in ten days“

During this time, two major Reforms took place in Centro: one on the federal level, carried out in the harbour area by President Rodrigues Alves, and the other by mayor Pereira Passos, which focused on the old colonial urban fabric of the city. Besides matters of insalubrity, Passos’ project aspired to the aesthetic of European cities, and many of its key ideas were taken from Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Reform, which less than a century before drastically changed the image of Paris.

Central to the initiative was the demolition of collective housing complexes, considered by public authorities unfit and the focus of several diseases, and the creation of wide avenues to accommodate vehicular traffic and pedestrian flow36. Under the veil of public health measurements, roughly twenty thousand people lost their homes to the project37, disproportionally affecting lower-income communities - who, until this point, had always lived in the central area of the city, especially in the harbour region. This led both mayor and in motion reform to be popularly known as Bota-Abaixo38. Besides the spatial changes that took place during this period, one of the first measurements of mayor Pereira Passos was the prohibition of informal trading, which directly affected the lower-income population of the city, that very much relied in this type of work. Concurrently, it increased profit from merchants39, accentuating the pre-existing economic gap in Rio de Janeiro. It is also worth mentioning, that very few new popular housing complexes were built, in order to reallocate the evicted populations of Centro40

“… it (Centro) was gradually losing its picturesque and unmistakable appearance as a great Portuguese villa. The ugly, heavy colonial buildings had been modified and archaic commercial uses had been banished. She had abandoned her unflattering clothes forever, as if in a gesture of repulsion from a lady of high distinction. She wanted to be young and beautiful, with cars whetting her craving for a full and comfortable life.”41

Although the Bota-Abaixo was successful in diminishing the incidence of several diseases, the reform had a strong impact in the social-spatial organisation of Rio de Janeiro until this day. Passos’ Reform is held as one of the primary reasons for the accelerated process of favellisation42 that took place from 1900s onwards, as evicted marginalised groups sought for housing alternatives in the outskirts or slopes of the city.

36 Schumtzler Abrahão, “O “BotaAbaixo” De Pereira Passos: Transformação Urbana Como Artifício Civilizatório?”, Trabalhos De Antropologia e Etnologia, 2022, 162.

37 Lucas Faulhaber & Lena Azevedo, SNH: As Remoções No Rio de Janeiro Olímpico (Rio de Janeiro: Mórula, 2015), 36.

38 Engl.: to demolish.

39 Lessa, O Rio de Todos os Brasis, 2000 quoted in Abrahão, “O “BotaAbaixo” De Pereira Passos”, 162.

40 Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, 86.

41 Francisco Agenor Noronha Santos, Meios de Transporte no Rio de Janeiro 1934 quoted in Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, 86.

42 From the Brazilian Portuguese favelização, it is the spatial process of forming a favela.

43 Schumtzler Abrahão, “O “BotaAbaixo” De Pereira Passos”, 163.

44 Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, 100.

45 Abreu, A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, Abreu, 100.

Fig. 18: “Alargamento da Rua Uruguaiana“, picture by Augusto Malta, 1905. Available at: Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileira, https://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org. br/obra19714/alargamento-da-ruauruguaiana (last accessed on March 8, 2024)

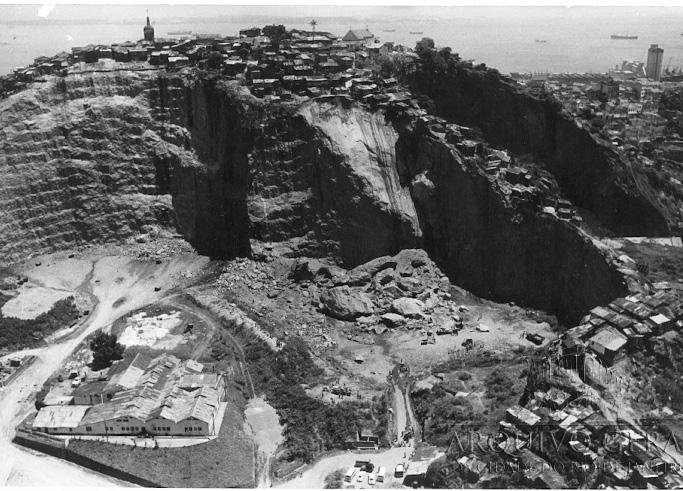

Fig. 19: „Desmonte do Morro do Castelo“, picture by Augusto Malta, 1922. Available at: Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileira, https://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org. br/obra19718/desmonte-no-morrodo-castelo (last accessed on March 8, 2024)

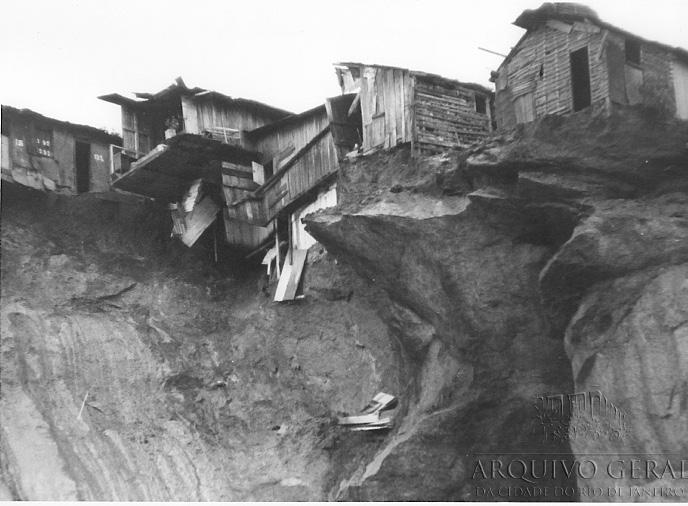

Fig. 20: Picture by unknown. Available at: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

Fig. 21: Picture by unknown. Available at: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

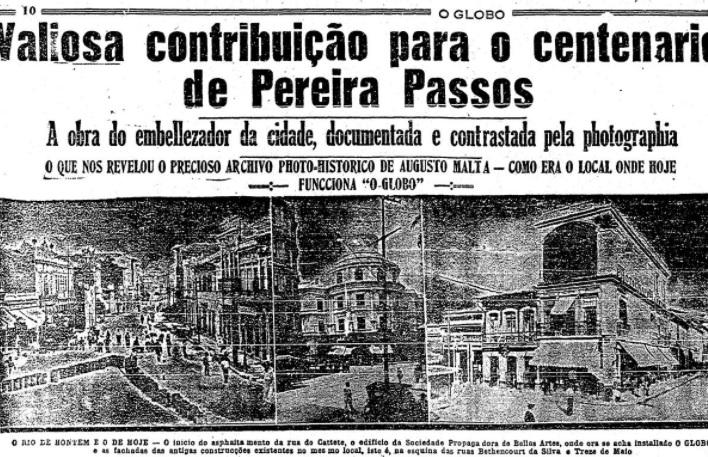

Fig. 23: Cover of O Globo (local newspaper), at August 1, 1936. Available at: Cronologia de Augusto Malta, Brasiliana Fotografica, January 6, 2021, https://brasilianafotografica. bn.gov.br/?p=20908 (last accessed on March 8, 2024)

“(…) as they were forbidden to work and move around the city centre, stigmatised in a profile of potential risk of contagion and bad habits and customs, they had the alternative of migrating to the outskirts of the city or to steep hills in search of affordable but precarious places to live.”43

In the subsequent years, additional urban interventions reshaped Rio’s central area. In 1922, mayor Carlos Lacerda sanctioned the implosion of Morro do Castelo, hill where the city was first founded. Despite its historical importance, the hill had become home to working-class families, and the decision was justified by the improvement of air circulation in the area44. Also, the houses at the foot of the hill were demolished, making space for the International Exposition celebrating 100 years of independence45. With the growth of the city towards the South and North Zones, the spatial segregation became even more pronounced. Public funds flowed predominantly to the new South Zone, catering to the elite, while the North Zone became characterised by popular housing complexes and industrial zones. Slowly, Rio de Janeiro witnessed its bustling downtown centre being shaped and transformed into a political and economic symbol, only to subsequently decline in the ensuing years.

While cortiços kept on being teared down at sea level, the hills of the city were slowly occupied by rudimentar dwellings. Images of Pereira Passos‘ Bota-Abaixo, in 1905 and the implosion of Morro do Castelo, in 1922. At the bottom, first settlements at Morro da Favela, today Morro da Providência, in the harbour region.

Cover of local newspapers celebrating the urban renewals by mayor Pereira Passos. At the top, text reads: “Pereira Passos orders the demolishment of colonial Rio: With the new mayor pereira passos, it becomes clear that Rio de Janeiro will no longer be a fetid, disease-ridden city. In place of the ‘cemetery of europeans‘, an unflattering nickname that the capital of the republic had earned, the city will be reborn as the grandest example of the tropical belle époque.“

The urban reforms of the early 1900s strove for a Rio de Janeiro comparable to major European centres, with the central area mirroring the city’s status as the federal district, cultural and political hub of Brazil. However, this vision underwent a significant shift in the 1960s with the transfer of the country’s capital to Brasília, resulting in the loss of one of Rio’s main economic driving forces. Concurrently, other regions of the country underwent industrialisation, diminishing Rio’s economic significance46. As a direct consequence, the downtown area experienced an increase in vacant buildings and a decline in overall relevance. This trend was further exacerbated by the suburban expansion, drawing not just the middle classes towards the South Zone, but also attracting industries and working-class to the North and West Zones of the city. This is also explained by the production of housing complexes in neighbourhoods such as Realengo, Bangú and Marechal Hermes 47 .

In 1976, a decree48 accelerated this process even further, by prohibiting the construction of residential buildings in nearly the entire central region - influenced by Modernism’s functionalist ideology, prevalent in Brazil’s urban planning. This policy lasted until 1994, a period where the population in Centro further decreased in 23% (and 33% in the harbour area), while Rio de Janeiro had a demographic increase of 40%49.

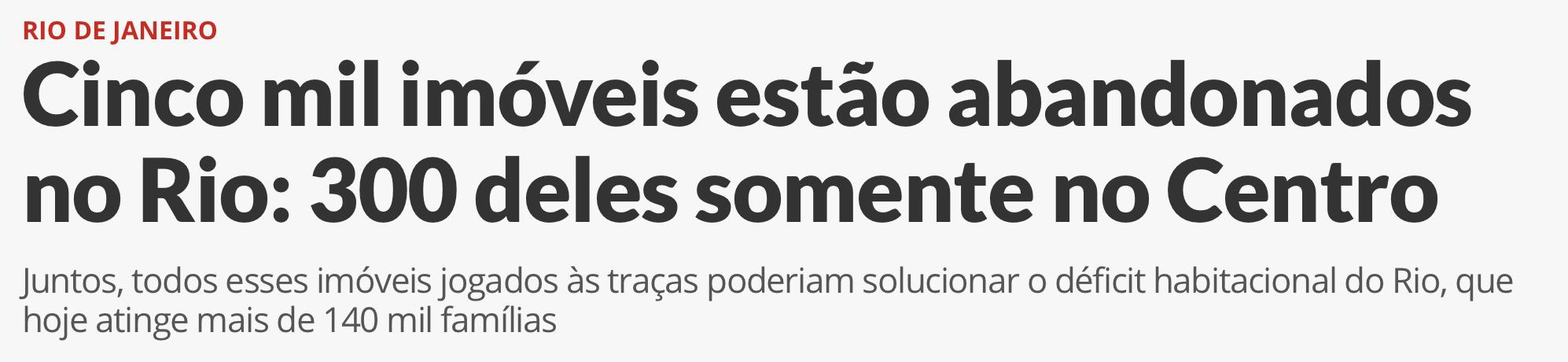

The cumulative urban changes throughout the twentieth century have profoundly shaped Centro’s current composition. In 2021, program Centro para Todos (CPT) released a mapping of abandoned buildings within the central area50, focusing on the perimeter between Lapa, Cruz Vermelha and Praça XV. Out of over four thousand buildings analysed, 549 were found to be vacant, 329 were subtilised (with either only the ground floor or the upper floors) and 53 were in ruins. The study also identified 82 vacant plots, concentrated around the areas of Lapa, Saara and Cruz Vermelha. Following the collapse of a townhouse in Praça XV in October 202351, Centro’s subprefecture conducted another survey52, identifying 158 vacant buildings at risk of collapsing. Although both surveys offer some insight into the current situation of Centro, precise data regarding the total number of abandoned buildings across the entire central area (AP1) remains elusive. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to suppose this pattern extends to non-analysed regions.

46 Matheus da Silveira Grandi, “Práticas Espaciais Insurgentes e Processos De Comunicação: Espacialidade Cotidiana, Política De Escalas e Agir Comunicativo No Movimento Dos Sem-teto No Rio de Janeiro” (master thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2010), 168.

47 Nelson da Nóbrega Fernandes, „Capitalismo e Morfologia Urbana Na Longa Duraçao: Rio de Janeiro (Século XVIII-XXI)“, Diez Años de Cambios en el Mundo, en la Geografía y en las Ciencias Sociales, 2008, n.pag.

48 Decree Lei nº322, de 3 de Março de 1976

49 Ivan Zanatta Kawahara, “O Papel do Estado Na Promocao Da Segregacao Na Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, XVI ENANPUR: Espaco, Planejamento E Insurgencias, 2015, 18.

50 DATA RIO Programa Centro Para Todos - Survey And Mapping Of Empty And Underused Properties In The Centro Area, accessed on February 25, 2024, https://www.data.rio/documents/646eb634f98b447098b9a98f45da1955/explore

51 Beatriz Perez, “Caminho Fechado: Desabamento De Casarão Interdita o Arco Do Teles e Ameaça Estruturas”, O Dia, October 20, 2023, https://odia.ig.com.br/ rio-de-janeiro/2023/10/6727455caminho-fechado-desabamento-decasarao-interdita-arco-do-teles-eameaca-estruturas-vizinhas.html

52 Luiz Ernesto Magalhães, “Centro Do Rio Tem 158 Imóveis Abandonados. Saiba Quais São As Ruas Com Prédios Em Pior Estado”, Extra, October 18, 2023, https://extra.globo.com/rio/ noticia/2023/10/centro-do-rio-tem-158imoveis-abandonados-saiba-quais-saoas-ruas-com-predios-em-pior-estado. ghtml

Fig. 24: Concentration of vacant buildings. Drawing by author, based on map from CPT‘s 2021 study. Available at: DATA RIO Programa Centro Para Todos - Survey And Mapping Of Empty And Underused Properties In The Centro Area, https://www.data.rio/ documents/646eb634f98b447098b9a98f45da1955/explore (last accessed on February 25, 2024).

Right: Incidence of vacant buildings in the R.A. II, 2021.

53 Grandi, “Práticas Espaciais Insurgentes”, 168.

54 Rafael Galdo & Selma Schmidt, “Cidade Do Rio Tem 1.123 Imóveis Públicos Em Nome Dos Extintos Estados Da Guanabara e Prefeitura Do Distrito Federal”, O Globo, September 26, 2021, https://oglobo.globo.com/ rio/cidade-do-rio-tem-1123-imoveispublicos-em-nome-dos-extintos-estadoda-guanabara-prefeitura-do-distritofederal-25213244.

Guanabara was a short-lived Brazilian state that emerged as an outcome of the transfer of Brazil‘s capital to Brasília, in 1960. The former federal district was transformed into the state of Guanabara, with Rio de Janeiro as its capital. 15 years later, Guanabara was absorbed into the state of Rio de Janeiro.

55 Grandi, “Práticas Espaciais Insurgentes”, 168.

56 Predicted in Articles 182 and 186 of Brazil’s 1988 Federal Constitution.

Fig. 25: Different headlines on Centro‘s high vacancy over the last 10 years. Collage by author.

Another facet concerning Centro’s vacancy is the prevalence of empty buildings owned by the State, many of which coming from old administrative purposes, or acquired by public entities through debt payments53. Additionally, there are 1.123 edifications across Rio de Janeiro which are still property of the dissolved Federal District of Rio de Janeiro and State of Guanabara54, with the transfer of ownership to the current State of Rio de Janeiro not occurring automatically. This complicates efforts to refurbish and preserve these structures, which all too often end up empty. Other remaining buildings are associated with the port’s industrial activities and are kept vacant by companies for speculative purposes and as capital reservoir55.

In this context, empty buildings will be understood as housing possibility, and their higher presence in Centro will contribute to the argument of reoccupying central areas by historically marginalised populations. Social movements for housing rights demonstrate a special interest in state-owned buildings, viewing their vacancy as a direct contradiction to the social function of property56 and the government’s obligation to provide adequate housing for all citizens.

Despite undergoing a population decline over the twentieth century, Centro never truly lost its vitality. The shift in the city’s development towards other areas led to an abandonment of the central region by the local elite, who established new shopping hubs in the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca57. Nevertheless, Centro endured as a commerce and services hub, largely fuelled by informal trade which became officially recognised within Rio‘s urban economy in the 1980s58. The central area also kept on as an important business and political centre, housing most of Rio de Janeiro’s state apparatus and the second-large business district in the country, the Área Central de Negócios do Rio de Janeiro59 .

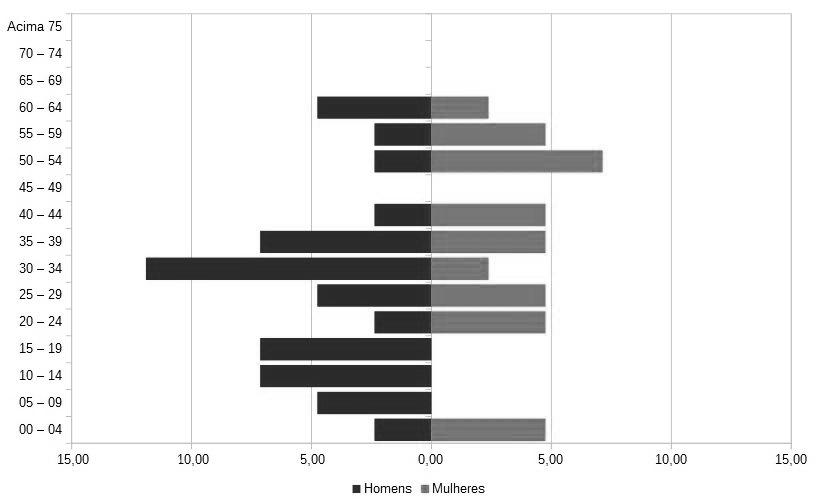

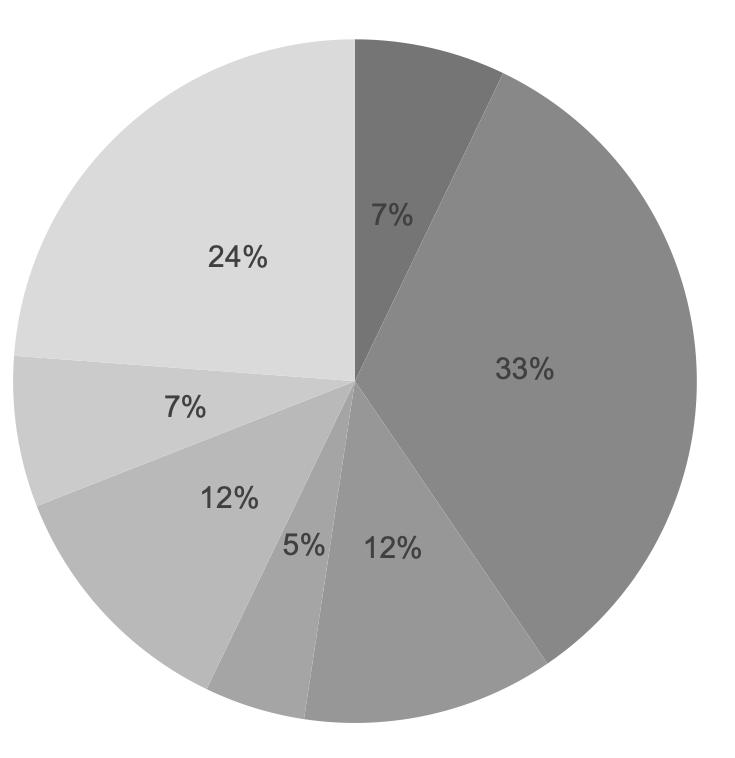

In this narrative, despite efforts to gentrify and purge residential life from Centro, lower-income groups persistently returned, occupying the region through informal settlements. This is evident by the significant population surge experienced in Centro between 2000 and 2010, particularly in the R.A. Portuária (Fig. 26), crossed with the overall income decline of the region’s residents (Fig. 27).

This development will be perceived by the local elite as further evidence of “degradation”, which summed with the high number of vacant buildings, prompted a series of urban plans for the region throughout the twentieth-first century. To validate such initiatives, the discourse of “urban decay” assumes vital importance, as portraying Centro as a

“(…) degraded central region, relegated to a ‘marginal’ population (street vendors, beggars, prostitutes, homeless people, abandoned minors, and the poor in general), already includes a solution. Since it has become a recognisably ‘lifeless’ space, it needs to be ‘revitalised’: ‘It’s a double movement: making the Centro viable as a place of poverty in order to return it to its former place of wealth”60

Amidst this backdrop, various strategies were drawn with the premise of revitalising the region and boosting overall tourism in the city, thus regaining the “lost image” of the cidade maravilhosa61. This led to several measurements taken by the local government, such as programs Rio-Cidade62 and FavelaBairro63. Moreover, Rio pursued the bid to host the 2004 Olympic

57 Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 44.

58 Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 57.

59 Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 56.

60 Edson Miagusko, 2008 quoted in Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 45.

61 Engl.: Marvelous city

62 Rio-Cidade was an urban program sanctioned by mayor Cesar Maia (19931997) and continued over the following years. It aimed on improving the overall infrastructure of the city, such as sewage, lightining and rainwater dreinage.

63 Favela-Bairro was a program institutionalised during Cesar Maia‘s tenure (1933-1997), with the main goal of urbanising favelas - safer constructions, sewage infrastructure, leisure spaces and so on. The program was discontinued in 2010 and replaced by Eduardo Paes‘ Morar Carioca - and re-activated in 2017 (now in its IV phase).

Fig. 26: Population according to the Planning Areas (Aps) and Administrative Regions (R.A.)1991/2010. Source: Adapted to english from Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 65.

Fig. 27: Average income according to housing situation - in R$. Source: Adapted to english from Mello, Trajetórias, Cotidiano e Utopias, 65.

Population according to Planning Areas (APs) and Administrative Regions (R.A.) - 1991/2010 Average income according to housing situation - in R$ -

Administrative Regions

House owner (paid-off) House

(monthly instalments)

64 Named Rio Sempre Rio, this urban plan was the first strategic plan for a city in the south hemisphere. In the document, the project of the city is based on two main characteristics: the urban space should be competitive and welcoming. Released in 1995, the plan has been reviewed and redrafted every four years.

65 In the context of “rediscovery“ of Rio‘s colonial city centre, SAGAS aimed on preserving historical buildings in the harbour region of the city.

66 A more detailed description of the project and the political machinations that ensured its realisation is available at: Betina Sarue, “Quando grandes projetos urbanos acontecem? Uma análise a partir do Porto Maravilha no Rio de Janeiro”, Dados 61, 2018.

Games, which, although unsuccessful, prompted the drafting of the First Strategic Plan for the City of Rio de Janeiro64. Aligning with the global trend of redeveloping harbour areas across the world, exemplified by projects such as London’s docklands, and Baltimore’s Inner Harbour, Rio’s local government explored ideas for the R.A. Portuária as early as 1983, with initiatives like SAGAS65 (Saúde, Gamboa, Santo Cristo), and Porto do Rio, in 2001.

However, it wasn’t until the coordination with mega-events like the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Rio Olympic Games, that sufficient resources on a federal and private level, coupled with consensus among Rio’s citizens, coalesced into the Porto Maravilha project66 - a consortium between private and public capital, with federal, state, and municipal investments. Backed up by “successful stories”, such as the Port Olímpic, in Barcelona, and Puerto Madero, in Buenos Aires, Porto Maravilha aimed to transform Rio’s “degraded harbour region” into a cultural, touristic, leisure, and business centre. Key urban developments within the scope of Porto Maravilha include (i) the demolition of the Elevado da Perimetral, a crucial thoroughfare linking various parts of the city, to enable visual and physical connection with the coastline; (ii) the construction of two museums, Museu de Arte do Rio (MAR) and Museu do Amanha, from architect Santiago Calatrava; and the (iii) implementation of a LRV (Light Rail Vehicle) system, connecting the neighbourhoods in the harbour region and the bus terminal, with Centro neighbourhood and the Airport Santos Dumont.

67 Detailed information on the evictions under the Porto Maravilha project are available at: Faulhaber & Azevedo, SNH: As Remoções No Rio de Janeiro Olímpico

68 Letícia de Carvalho Giannella, A produção histórica do espaço portuário da cidade do Rio de Janeiro e o projeto Porto Maravilha”, Espaço e Economia 3, 2013, 11.

69 Felipe Litsek et al., “Programa Reviver Centro “turbinado”: a expansão da lógica do mercado na requalificação da região central carioca”, Observatório das Metrópoles, April 13, 2023, https:// www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net. br/programa-reviver-centro-turbinadoa-expansao-da-logica-do-mercadona-requalificacao-da-regiao-centralcarioca/

Fig. 28: Porto Maravilha. Drawing by author.

Fig. 29: Picture by unknown, 2013. Available at: G1, Fotos: Demolição do Elevado da Perimetral, November 24, 2013, https://g1.globo.com/rio-dejaneiro/fotos/2013/11/fotos-demolicaodo-elevado-da-perimetral-.html (last accessed on March 8, 2024)

Fig. 30: Picture by Brenno Carvalho, 2020. Available at: Selma Schmidt, Zona Portuária: Uma Região de Contrastes, O Globo, February 2, 2020, https://oglobo.globo.com/ rio/zona-portuaria-uma-regiao-decontrastes-24210821 (last accessed on March 8, 2024)

Fig. 31: Rendering by Aflalo & Gasperini Arquitetos. Available at: Alison Furuto, “Trump Towers Proosal / Aflalo & Gasperini Arquitetos”, Archdaily, January 17, 2013, https://www. archdaily.com/317905/trump-towersproposal-aflalo-gsperini-arquitetos.(last accessed on March 8, 2024)

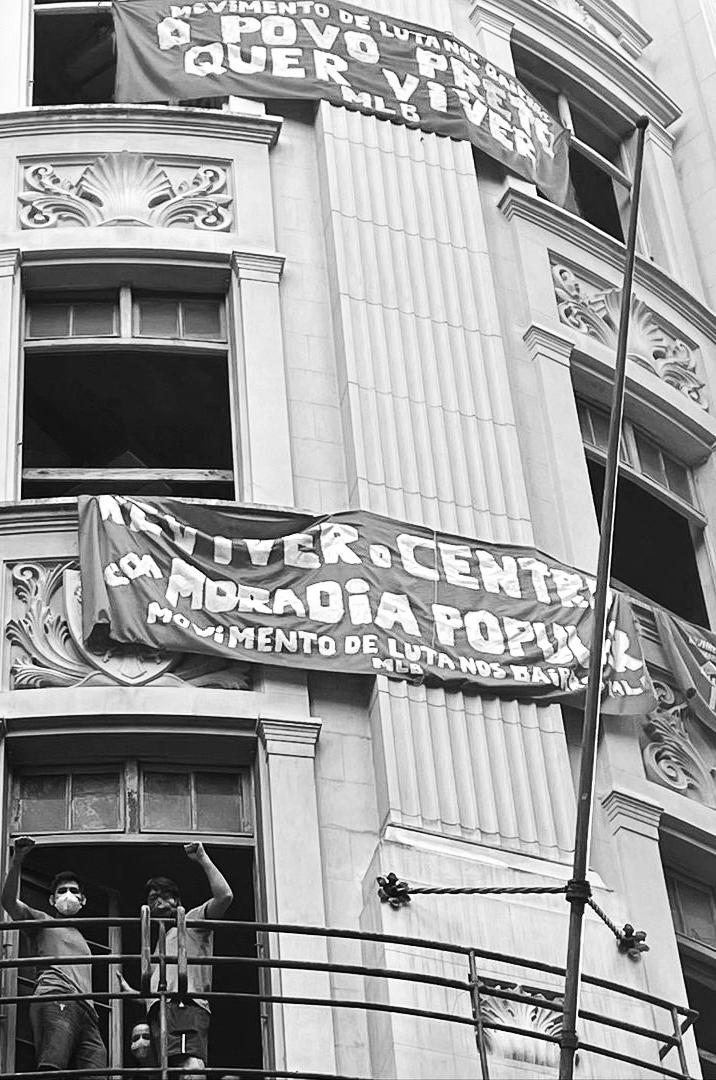

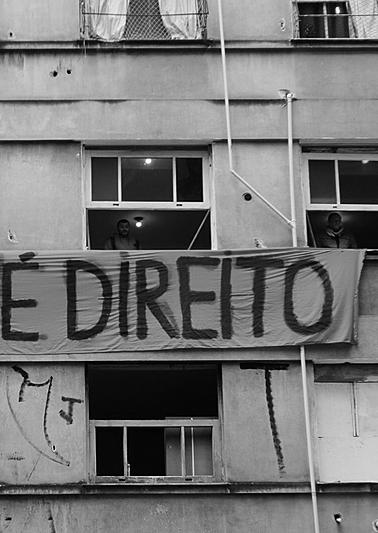

To ensure these measures and remove the region from its place of “decadence”, numerous forced evictions were carried out in the vicinity of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games67. Notable examples include Casarão Azul (2009), Flor do Asfalto (2011), Guerreiros do 510 (2009), Machado de Assis (2012) and Zumbi dos Palmares (2011) - all urban squats in the central area of the city. While the displaced families received social rent until being reallocated to social housing units, these were predominantly situated in the AP5, approximately 70 km away from their original homes and lacked adequate urban mobility infrastructure. In the more residential and historically significant parts of the harbour region, such as Morro do Pinto, Morro da Conceição and Morro da Providência, efforts focused on urbanisation and promoting tourism, while aiming to preserve the cultural identity and memories of the local population. However, “similar revitalisation projects have led to a sort of museification, that ends up driving out local populations and replacing them with a middle-class population eager to experience living or launching commercial ventures in a bucolic and charming environment”68. Evictions were also underway in these areas, justified by claims of hazardous conditions posing risk to resident’s lives.

With Brazil’s economic and political crisis from 2013 onwards, many investors withdrew from the project, leaving the area with underutilised urban infrastructure. In 2020, a study depicted that during the first decade of the program (2010-2020), only 77 new establishments were licenced in the whole harbour region, including the reform of existing buildings, a very small amount considering the plan’s coverage area69. Today, Rio’s harbour region grapples with emptiness, as Porto Maravilha did not prioritise residential or affordable housing. Instead, the focus was on attracting private investments for corporate buildings and tourism-related facilities, resulting in a population density that fluctuates with working hours and holidays.

Left: Porto Maravilha‘s coverage area and main urban works of the program.

Rendering of the Trump towers, in the harbour area. Complex would be the biggest corporate centre in Brazil, with 38-floors across 5 buildings. The first two towers should had been completed in time for the 2016 Olympic Games, but construction works never started. The area destined for the project had been partially occupied by squat Quilombo das Guerreiras, evicted in 2014.

Corporate complexes, glass facades and high-rise buildings were part of the moodboard for a new, revitalised harbour area.

In 2021, re-elected mayor Eduardo Paes70 launched a new plan for the central area of the city: Reviver Centro. Unlike its predecessor Porto Maravilha, which also took place under Paes’ administration, the project focuses on strategies for the refurbishment and preservation of historical buildings in Centro and multifamily housing. This approach gained heightened significance following the Covid-19 Pandemic, as the low housing density in the region and absence of mixed-use buildings left the streets of Centro deserted even during daylight hours, contributing to increased criminality and stigmatisation by the population.

“The Reviver Centro Program aims to attract residential use, promote different income brackets, change the perception of Centro, and implement lasting revitalisation, bringing a more dynamic lifestyle to Centro. In this sense, the program aims to protect and expand residential areas, encourage the retrofitting of buildings with benefits, improve public services, promote culture, and present the centre as a modern and dynamic region.” 71

Although preservation and investment in central areas are crucial and warrant further exploration, there remains a persistent risk that processes of gentrification comes concealed under terms such as revitalisation. This concern is particularly pertinent for Centro, given the region is predominantly inhabited by lower-income groups in informal settlements, such as favelas, squats and cortiços72,making them more susceptible to urban transformations. In the case of Reviver Centro, several aspects of the program raise concern regarding its inclusivity for the existing population73. These include the (i) project coverage area, which exclude Morro da Providência and Caju, and is not aligned with previous Porto Maravilha74; (ii) lack of an action plan regarding the 2015 approved Plan for Social Housing in the Harbour Region (PHIS)75; (iii) oversight of cortiços; and (iv) deficiency of popular participation76.

Following the wave of evictions that took place under Porto Maravilha, current urban plan Reviver Centro once again fails to address the needs of current inhabitants, focusing solely on attracting new residents to the area. Although increasing housing density is a commendable goal, it must be pursued in collaboration with the existing population, as to avoid inadvertently displacing lower-income classes through gentrification.

70 Eduardo Paes is a politician from Partido Social Democrático (PSD). He was first elected mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 2009, position he occupied until 2017. In 2021, he was once again elected and is current mayor of the city.

71 Oscar et. al, “O Programa Reviver Centro E Sua Proposta Para Mitigar Problemas Urbanos.” XIX Encontro Nacional de Tecnologia do Ambiente Construído, 2022, 6.

72 A 2021 Study by Observatório das Metrópoles points out there are at least 155 cortiços in Centro, with approximately 2.638 inhabitants. About 100 of those are in the Reviver Centro coverage area. Available at: Observatório das Metrópoles, “Projeto Prata Preta: levantamento de cortiços da área portuária do Rio de Janeiro”, June 4, 2019, https://www. observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/ relatorio-corticos-na-area-central-do-riode-janeiro/.

73 Tarcyla Fidalgo et al., “Reviver O Centro. Para Quem? Análise Preliminar Sobre O Programa Apresentado Pela Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro”, Observatório das Metrópoles, May 20, 2021, https:// www.observatoriodasmetropoles. net.br/reviver-o-centro-para-quemanalise-preliminar-sobre-o-programaapresentado-pela-prefeitura-do-rio-dejaneiro/.

74 In the article by Fidalgo et al. the coverage area also does not include the neighborhoods of Santo Cristo, Saúde and Gamboa, which are all part of the R.A. Portuária. However, the official website of the project does mention the area, which leads to believe that the plan suffered alterations since its launch in 2021. Regardless of such, only R.A. Centro is under direct administration of the City of Rio de Janeiro, while R.A. Portuária lays under the administration of Companhia de Desenvolvimento Urbano da Região do Porto (CDURP).

75 The Porto Maravilha Social Interest Housing Plan (PHIS) was designed to be a social counterpart to the public investment coming from the FGTS Fund for the consortium urban operation of Rio de Janeiro‘s port region. However, until 2017, the Porto PHIS has only delivered 24 housing units, out of a target presented by Rio City Hall of around 5,000 units. Mariana Werneck, “Habitação Social no Porto Maravilha: Cadê?”, Observatório das Metrópoles, May 24, 2017, https://www. observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/ habitacao-social-do-porto-maravilhacade/.

76 Fidalgo et al., “Reviver O Centro. Para Quem?”, Observatório das Metrópoles

77 Fidalgo et al., “Reviver O Centro. Para Quem?”, Observatório das Metrópoles

78 One of the proposed mechanisms by the plan is, for example, the so-called interconnected operation - where construction companies receive incentives to build in other valued areas across the city, such as Copacabana, Ipanema, Lagoa, and others.

79 Litsek et al., “Programa Reviver Centro “turbinado”, Observatório das Metrópoles.

80 Litsek et al., “Programa Reviver Centro “turbinado”, Observatório das Metrópoles

81 Litsek et al., “Programa Reviver Centro “turbinado”, Observatório das Metrópoles.

82 Porto Maravilha Social Interest Housing Plan.

83 Marcelo Edmundo, WhatsApp Message to author, March 1, 2024.

Fig. 32: Picture by author, taken on December 2, 2024.

Fig. 33: Reviver Centro. Drawing by author.

“(…) even if the public authorities don‘t remove people, the program presented could start a process of gentrification, with the indirect expulsion of the poorest population, increasing the prices of living in the central region and changing the uses of spaces. Despite providing for the development of programs, such as Social Rental and Assisted Housing, the project does not make it clear how they will work.”77

In 2023, the plan was revised and altered by Lei Complementar n 109/2023, increasing the incentives and concessions to the real state sector, as to boost transformations in the area78. This confirms the already observed logic of the market which permeates the urban plan, with the danger of construction companies and real state dictating and shaping the area to their own interests79. In the two years of program, there has also been an observed tendency of endeavours composed by studio apartments, with a maximum of 30 square metres each80. This excludes lower-income population and families, prioritising units for seasonal rental, such as Airbnb’s81. Also important to note is the lack of public participation in the project, which had already been the case during the Porto Maravilha.

“There was no participation! We even asked for it and nothing happened! The movements and not even the local residents and organisations. Zero participation. (…) Unfortunately, these projects did not bring any improvements to the population living in the region, especially in terms of housing. (...) There are more than 6 thousand housing units being built in the harbour region and not one, not one is destined to social housing (HIS), even though they are predicted in the harbour’s PHIS82 plan.”83

While it is premature to ascertain the long-term repercussions of Reviver Centro, there is a risk that the plan may mirror the observed trend from Porto Maravilha and other urban projects since the late nineteenth century, gradually displacing the local population of Centro, to accommodate middle-class housing and corporate developments. Thus, erasing the historical memory of slaves and working class, who have shaped, resided, and laboured in the area throughout Rio’s history. And who share deep sense of belonging with the region, especially concerning the Pequena África.

Portuguese arrive in Rio de Janeiro.

Colony (1500-1822)

Official foundation of the city. Transfer of the capital from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. Construction of Cais do Valongo. Royal family arrives in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro is elevated to capital of Portugal‘s Empire.

Declaration of Independence. Rio becomes capital of Brazil.

Empire (1822-1889) Republic (1889-1964)

Prohibition of slave-trade in the Atlantics. Cais do Valongo is deactivated.

Implosion of cortico Cabeca de Porco.

Pereira Passos‘ urban reform (coverage of Cais do Valongo, mass evictions).

1502 1565 1763 1774 1808 1822 1831 1893 1903

Rio de Janeiro as capital of the country

Republic (1889-1964)

Implosion of Morro do Castelo.

Military dictatorship (1964-1985)

Transfer of the capital to Brasília

Sanction of decree prohibiting new residential buildings in the central area

1st urban plan for the harbour region: SAGAS 1976‘s decree is revogated. Population decreased 23% in Centro (33% in the harbour region)

Democracy (1985-today)

Porto Maravilha. Brazil‘s Worldcup. Rio Olympic Games Reviver Centro

The right to housing is ensured in Brazil’s 1988 Federal Constitution (article 6)81, as well as in the World Charter for the Right to the City82. Nevertheless, access to adequate housing remains one of the most pressing urban challenges in the country. As previously mentioned, Brazil’s rapid urbanisation in the twentieth century led to a significant shortfall in housing supply compared to the growing urban population. This produced a housing crisis, characterised by overcrowded tenement houses and the proliferation of informal settlements, the favelas, on the outskirts and slopes of cities.

In this period, the number of informal settlements in Brazil skyrocketed, with approximately 16 million people currently residing in favelas83, constituting roughly 11% of the country’s entire population. The “problem of the favela”84 has become emblematic of urban life in Brazilian cities, often referred to as the Brazilian “housing apartheid”85. This term underscores the significant spatial segregation and socio-economic disparities that persist in urban areas, largely attributed to inadequate housing policies and systematic government displacement efforts. Although not an enforced segregation, the high levels of inequality in Brazil exacerbate the difficulties faced by lower-income families in accessing the “formal city”. This is amplified by the country’s history of slavery, with poverty rates disproportionately affecting black populations. In 2022, the proportion of poor individuals among white Brazilians stood at 18.6%, compared to 34.5% among black Brazilians and 38.4% among pardos86 87 .

“The process of intense migration to large cities, capitals, and their peripheries, combined with the population‘s high birth rates and the absence and inadequacy of urban and housing policies in Brazil, contributed to a wave of explosion of the peripheries by working class families who, without counting on help or support from the state, were forced to build their own homes, neighbourhoods, and infrastructures under intense and lasting sacrifices.”88

81 “Art. 6 Social rights are education, health, food, work, housing, transport, leisure, security, social security, protection of motherhood and childhood, assistance to the destitute, in the form of this Constitution.“ BRASIL. Const. 1988. Art. 6.

82 The Charter was first elaborated in the Social Forum of the Americas in 2004 and “aims to gather the commitments and measures that must be assumed by civil society, local and national governments, members of parliament, and international organizations, so that all people may live with dignity in our cities“ World charter for the right to the city, 2004, https://www.uclg-cisdp. org/sites/default/files/documents/ files/2021-06/WorldCharterRighttoCity. pdf (last accessed on March 6, 2024)

83 IBGE / CENSO 2022, accessed on March 5, 2024, https://censo2022.ibge. gov.br.

84 Favelas will be regarded as problematic by urban policies in Brazil and have been since the twentieth century the centre stage of multiple eviction policies.

85 João Vargas makes use of the term in the article “Apartheid brasileiro: raça e segregação residencial no Rio de Janeiro”, Revista de Antropologia v.48, n1, 2005. The term has also been widely used in the media.

86 Engl.: mixed-race. The term pardo is one of the 5 used by Brazil’s Statistic Centre to describe Brazil’s population. Although officially utilized, the term has suffered criticism by black movement activists, as it may indirectly lead to an whitening of the population.

87 IBGE / CENSO 2022, accessed on March 6, 2024, https://censo2022.ibge. gov.br

88 Maricato, 1975 quoted in Francisco Comarú, Benedito Barbosa, Movimentos Sociais e Habitação (Bahia: UFBA, 2019), 15.

Fig. 34: Picture by Pablo Vergara. Available at: Pablo Vergara, “Ocupaciones verticales: sobrevivir en la región portuaria de Río de Janeiro“, El País, April 29, 2023, https://elpais. com/planeta-futuro/2023-04-30/ ocupaciones-verticales-sobrevivir-enla-region-portuaria-de-rio-de-janeiro. html#?prm=copy_link (last accessed on March 6, 2024)

The lack of access to housing worsened in Brazil from the late 1970s, coinciding with the period of military dictatorship. Economic instability, characterised by a negative GDP growth and rise in unemployment rates directly exacerbated the situation. As overall salaries failed to keep pace with escalating rent costs, thousands of workers were left without viable housing options89. Concurrently, processes of urbanisation in major Brazilian cities kept on at full speed, with informal settlements playing a pivotal role in shaping the urban fabric. For instance, in São Paulo, the surge in favelados was almost ten times greater than the population growth90, and precarious tenement houses became a sough-after housing solution amidst skyrocketing land values in the metropolitan region. In this climate, the “aspiration of ‘not paying rent’”91 became a necessity, as homeownership emerged as the primary defence against escalating rent costs.

While squatting had long been a reality in Brazilian cities, exemplified by the proliferation of favelas nationwide, it assumed a different character in the 1980s. Community groups such as Comunidades Eclesiais de Base92 and neighbourhood’s associations emerged as focal points for discussing the housing crisis and possible solutions, serving as base for the articulation of first housing rights movements. Within this context, organised land squats start to appear, as for instance in Campo Limpo in 1981, followed by several others across the state of São Paulo, summing up to 61 squats and over 10.000 families by 198493

Meanwhile, in Vila Maria, a district in the state of São Paulo, residents of cortiços also began pressuring the government to address the high rent costs. Frustrated by the lack of support from existing social programs such as PROMORAR, which focused solely on people residing in favelas, they sought alternative solutions. Eventually, they engaged with engineer Guilherme Coelho, who had just been back from Uruguay. Having observed first hand the success of Uruguay’s mutual aid cooperatives, the Cooperativas de Vivienda por Ayuda Mútua (FUCVAM), the engineer sought to start a similar project in São Paulo94. There, over 10.000 housing units had been built by cooperatives and mutual aid initiatives, with construction works and administration being done by future dwellers themselves.

89 Nabil Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão: Construindo territórios de utopia (Rio de Janeiro: Fase, 1992), 22.

90 Taschner, 1978 quoted in Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 24.

91 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 26.

92 Engl.: Basic Ecclesial Communities.

93 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 28.

94 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 35.

95 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 35.

96 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 36.

97 Created in 1965, Cohab is a state company dedicated to public housing policies. It finances the construction of houses to low-income classes.

98 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 36.

99 For example, the Banco Nacional de Habitação

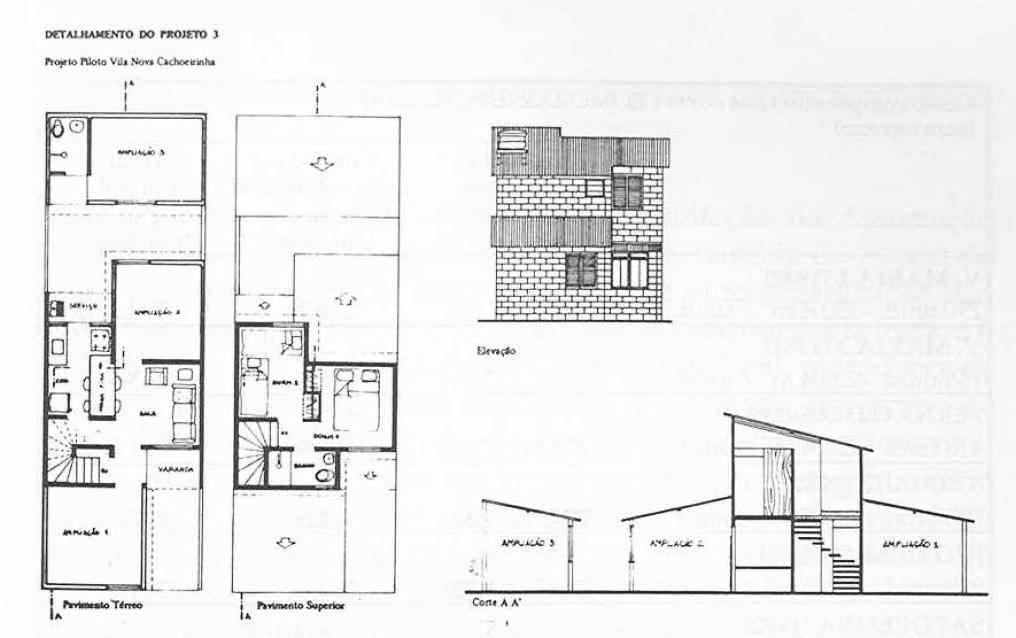

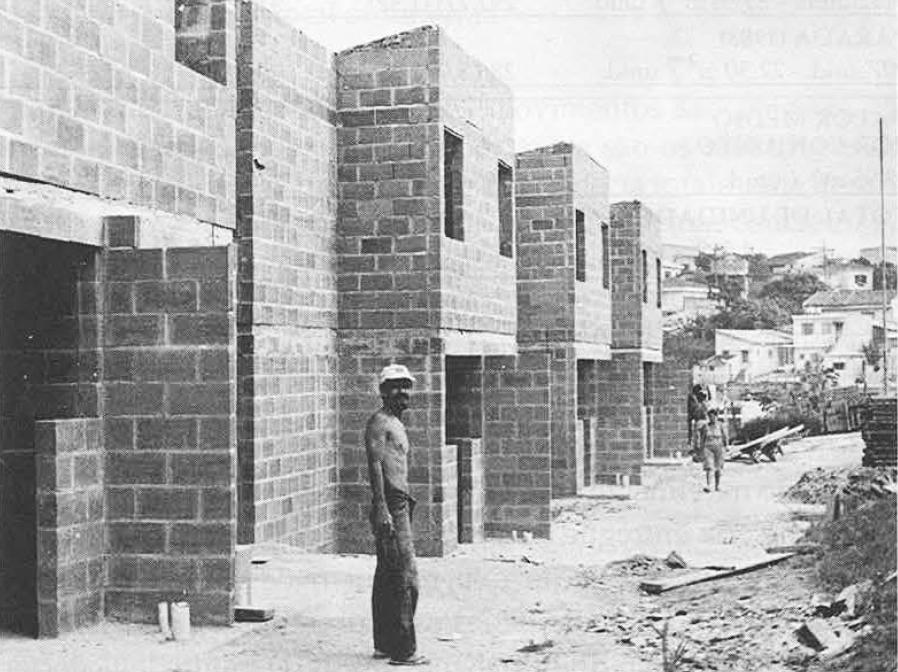

Fig. 35 (next page): Architectural drawings for Vila Nova Cachoeirinha. Drawing by unknown. Available at Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 37

Fig. 36 (next page): First built units at Vila Nova Cachoeirinha. Picture by unknown. Available at Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 37.

“In Uruguay, more than 10,000 housing units had been built through mutual aid co-operatives. This is a significant number in the face of a population of just over two million. In this system, the construction work and administrative management is done by the future residents (self-governance). The organisation acquired by the groups during the construction works led the residents to tackle other common social problems collectively. Health centres, crèches, libraries, consumer cooperatives - some of which were also self-managedemerged, helping to create community living spaces and improve the living conditions of the residents. Initially, some pilot experiments showed the potential of the system in 1966 and, in 1968, the National Housing Law regulated the proposal.”95

Inspired by the success of the Uruguayan project, the 400 families at Vila Maria submitted a housing proposal to the local government, securing a plot of land at Vila Nova Cachoeirinha96. Similar to the Uruguayan case, future residents dedicated a technical team separate from governmental entities, actively participating in the project’s planning phase and construction. This collective effort resulted in the construction of a prototype house, showcasing the cooperative’s potential in creating superior and more affordable housing through communal effort, in contrast to units built under the management of Cohab97 98 .

The case of Vila Nova Cachoeirinha marks the beginning of self-managed housing in Brazil, which remains a cornerstone of housing rights movements to this day. This model upends the conventional approach to social housing in Brazil, which relied on privatised production financed by public resources99. Instead, self-managed housing challenges market logic by emphasizing collective action, shared responsibilities, active participation, and mutual assistance among residents. At this point, the movement was also very much attached to the idea of self-construction (of new units) as a guiding principle to self-management housing, as it reflected a proactive response to the acute shortage of affordable accommodation.

& the right to the centre

Following Brazil’s re-democratisation in 1985, the political landscape became more conducive to social movements. The frustration with public housing policies, such as Banco Nacional de Habitação (BNH)100, prompted housing activists to also tackle the public sphere. The BNH was implemented during the Military Dictatorship, in 1964, and had as main objective addressing the country’s housing deficit, through funding of housing units for lower-income classes and attracting financial capital to the housing sector. Despite contributing to the construction of millions of housing units, the plan faced criticism for excluding the lowestincome sectors of society, as it did not contemplate families with an overall income of ≤ 3 minimum wages, and was surrounded by fraud scandals until its closure in 1986. In this context, movements began advocating for policy reforms, navigating two different fighting frontiers: the direct action through squatting, and the claim of action, through pressure and grassroots mobilisation101. These efforts culminated in the 1988 Federal Constitution102, which institutionalised several social rights in motion until today. One of the main achievements regarding the document are articles 182 and 183103, known as Pela Política Urbana, which defined the social function of urban property, as well as the juridic instruments of usucapion, key arguments when squatting vacant buildings. The Federal Constitution was also the first time the urban reform was addressed in Brazil, and although not all requests were covered by the document, it was an important step on the fight for the right to the city.

Still in the 1980s, first organised land squats also began to appear in Rio de Janeiro, as housing rights movements gained traction in the city. Additionally, as movements evolved, they began to recognise the untapped potential of vacant buildings as a viable housing option. Thus, principles of self-governance gradually adapted to suit the dynamics of urban squats in central areas. This was catalysed by the election of President Lula in the early 2000s, as several statements made by the President advocated for the repurposing of empty properties for social housing made the conjuncture even more favourable for squatting vacant buildings. This empowered housing movements against eviction104, and underpins their actions until today.

“There are buildings that can be turned into housing. There are buildings that we must sell and use the money to do something else. There‘s land, land and land that we can donate so that the price of housing is cheaper for the people (…) If it’s of no use for INSS (referring to the

100 Engl.: National Housing Bank.

101 Bonduki, Habitação & Autogestão, 33.

102 The 1988 Federal Constitution is Brazil’s currently active constitution. It was drafted during the process of re-democratization, after the ending of Brazil’s military dictatorship in 1985.

103 BRASIL. Const. 1988. Art. 182 & 183.

104 Matheus da Silveira Grandi, “Práticas Espaciais Insurgentes e Processos De Comunicação: Espacialidade Cotidiana, Política De Escalas e Agir Comunicativo No Movimento Dos Sem-teto No Rio de Janeiro” (master thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2010),174.

105 Given Interview by President Lula, December 2023.Available at: CNN Brasil, “Governo terá programa para destinar prédios nao usados pela União a moradia popular, diz Lula”, December 22, 2023, https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/ politica/governo-tera-programa-paradestinar-predios-nao-usados-pelauniao-a-moradia-popular-diz-lula/ .

106 Engl.: City Statute.

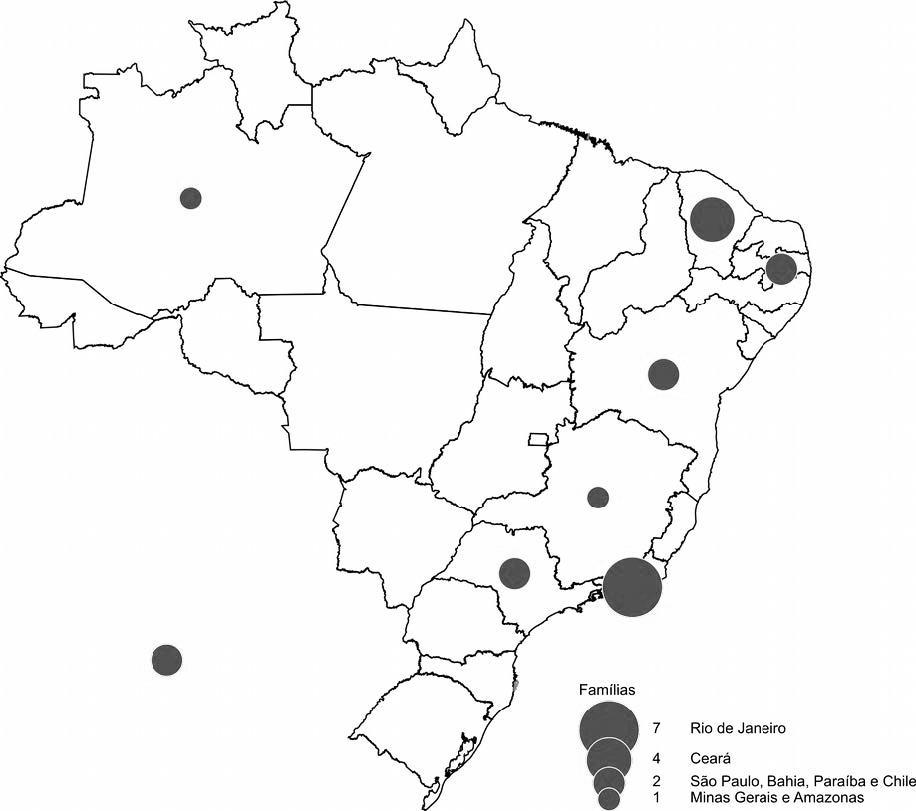

107 Engl.: Special Zones of Social Interest. The ZEIS defines urban areas to be destined to social housing, either being those already occupied by informal settlements and should be regularised, or still unoccupied plots close to urban infrastructure.