let it and

Reimagining Black and B R own l ife in the Rust Belt

BY gaVI n B en Jam I n

aR tist in R esidence t he w estmo R eland m useum of a me R ican aR t

Reimagining Black and B R own l ife in the Rust Belt

BY gaVI n B en Jam I n

aR tist in R esidence t he w estmo R eland m useum of a me R ican aR t

Down and Let It All Out:

The Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, PA

From the series “Museum Pictures”

Photographs and Artist Statement ©2023 Gavin Benjamin

Preface ©2023 Anne Kraybill

“In Conversation with Gavin Benjamin” ©2023 Erica Nuckles, Ph.D., and Jeremiah William McCarthy

“Within These Hallowed Halls” ©2023 Erika Butler-Jones

“Reflection from a Granddaughter of the Rust Belt” ©2023 Tara Fay Coleman

“It’s Not Enough Just to Remember…” ©2023 Jeremiah William McCarthy

“Notes on Developing Break Down and Let It All Out” ©2023 Pamela Cooper

All rights reserved. No part of this book maybe reproduced in any manner in any media, or transmitted by any means whatsoever, electronic or mechanical (including photocopy, film, video recording, internet posting or any other information storage and retrieval system) without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

First edition, 2024

Creative Direction: Gavin Benjamin

Design and Art Direction: Elsa Mehary

Project Management: Jacklyn Monk

Project Associate: Nina Friedman

Production Manager: Joan Weinstein

For more information on Gavin Benjamin, visit gavinbenjamin.com

Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let It All Out acknowledges the past, visualizes possibilities for the present, and gestures toward a more equitable future.

Benjamin, born in Guyana, South America, and raised in Brooklyn, New York, is a Pittsburgh-based photographer who reimagines the genre and traditions of portraiture. Aiming to connect with the African American residents of Greensburg, the artist invited numerous community members historically underserved by institutions—recent immigrants, first-generation Americans, and people of color—to sit for portraits and imagine their place within the Museum.

This exhibition combines the installation of a domestic space, owned by a fictional Black family for nearly 250 years, with psychologically rich portraits from the Museum’s collection. The setting is two paneled rooms, built around 1750 and designed by Swedish-Scottish architect Sir William Chambers, generously donated to the Museum in 1966 by Mrs. Cordelia Scaife May and Mr. Richard M. Scaife.

Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let It All Out is the inaugural project of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art’s new contemporary series. It was organized by the Museum’s Chief Curator, Jeremiah William McCarthy, and Director of Learning, Engagement, and Partnerships, Erica Nuckles, Ph.D. Additional support was provided by the Committee for the Westmoreland.

BY anne k R aYBI ll

It was a sunny day in October 2020 when I first met Gavin Benjamin with colleagues from the Westmoreland Museum of American Art. We were visiting studios in search of potential acquisitions. We had been living with COVID-19 for months, and it felt good to be in the physical company of others. As we learned more about Benjamin’s process, we quickly realized this visit would manifest into something beyond a mere acquisition of art for the collection. We grew excited as we discussed the visit and the possibility of an artist residency over a shared meal outside.

It was (and still is) a time of reckoning for art museums across the country. During the pandemic many museums laid off their visitor-facing staff, who are often the most diverse workers in an organization. Many institutions across the nation were sent

open letters demanding that they dismantle colonial and whitesupremacist models of operating. At the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, we wanted to be part of the change. We found ourselves genuinely trying to navigate this challenging time and engage in conversations about equity in a community that is not always perceived as diverse, welcoming, or inclusive.

I moved to Greensburg, the county seat of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in 2018, after accepting the role of the Richard M. Scaife Director/CEO of the Westmoreland. As part of my research prior to moving, I looked at census data and the history of the region. It is a place that was hit particularly hard when the steel industry collapsed, and many who had lived there left, resulting in an entire generation who would have been born there

coming into the world elsewhere. The population’s median age is 47, compared to the national age of 38. Racially the region is incredibly homogeneous, with almost 95% identifying as white. As new manufacturing industries tried to move in and a workforce in healthcare became paramount for the aging population, leaders realized that they had to attract new and diverse residents. But how could the community prepare to be welcoming and inclusive if it was not already acknowledging the diverse individuals, many of whom had lived for generations in the area?

Benjamin wondered, “How do folks of color survive in environments like this?” All communities are complicated, nuanced, and certainly not monolithic, and that is what Benjamin discovered as he embedded himself in Greensburg, a city in the greater

Westmoreland County. He met with residents who identify as Black or immigrants. He got to know them personally and learned what keeps them rooted in the community. The process was beautifully documented and revealed a mutual trust and respect that was established between the artist and the community. These were not transactional relationships of artist and subject—rather they were genuine friendships.

The resulting exhibition, Break Down and Let It All Out (2022), is a collection of beautiful portraits that center these residents of Westmoreland County in the tone of emotional release that Nina Simone speaks of in her song for which the exhibition is titled. Benjamin’s Break Down and Let It All Out reminds us all that the power of art can be extraordinarily healing.

My inspiration for Break Down and Let It All Out came after years of driving through Rust Belt cities with friends. I would often reflect on the question: How do people of color and immigrants exist within these often rural, industrial American spaces? As a Black, gay, immigrant artist and photographer living in the American Rust Belt, life can sometimes be isolating. It is isolation that has crept in and been woven into the fabric of AfricanAmerican history. Isolation one can feel vibrating on many levels. Isolation that has its roots in the history of colonialism, when the master would put Black families up for sale, to be sold off separately as no more than objects.

Walking through the doors of white institutions, such as museums, can leave you with that isolated feeling. Looking at the pictures on the walls and not seeing anyone who looks like me...I don’t belong. I was never here. Never existed. Isolation…

I want this series to break that achingly familiar pattern, by retelling these narratives. I want to show our people as leaders, upstanding family members, community builders, pioneers—strong, living rich and healthy lives. Something mainstream media often chooses not to focus on, because they assume it won’t sell enough products, get enough clicks, or they don’t believe people of color with integrity truly exist.

For me this is updating; reimagining our stories and bringing them into the present. It will be very challenging for institutions without the help and support of a multicultural workforce and a willingness to learn and change.

As a consummate student, I have learned so much from this project, and there is so much more that I am still learning. One of the biggest takeaways for me was the excitement of the local community. Some of these folks had never set foot in a museum, this museum. Before this experience, their reasons for not visiting included: “That space is not about me,” “I never felt invited,” and “There is no one that looks like me on those walls.”

To be seen within and on the walls of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, within its collection, has transformed this exhibition into a work of communitybuilding. For some Black folks within this community, this is the biggest event of their lives. I hope the Westmoreland continues reaching out to disenfranchised communities and pushing the boundaries of storytelling—so that our youth will know that they belong, in our Rust Belt cities and on the walls of any museum.

s ean Beaufo R d is a producer, independent curator, and museum worker concerned with engaging marginalized communities through culturally relevant, educational, and accessible programming. Since 2018 he has worked at the Carnegie Museum of Art as the Manager of Community Relationships. A selection of his writings can be found in the Bunker Review Artsy, and Public Source

eR ica n uckles p h .d. is an award-winning museum leader, educator, curator, and scholar. She currently serves as the Director of Learning, Engagement, and Partnerships at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art and has created dynamic experiences at museums and historic sites in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York. Nuckles resides in Ligonier, PA, with her husband, Drue Spallholz, where they own and operate the Eastwood Inn and Getaway Café.

ta R a faY coleman is a mother, conceptual artist, curator, writer, and arts worker from Buffalo, NY. She currently lives and works in Pittsburgh, PA. Fay’s work consists of a multidisciplinary praxis that is an exploration of identity, motherhood, Black womanhood, and taking up space. Through her practice, she mines her own lived experiences for subject matter, with a goal to intertwine her life with her work.

Je R emiah

w illiam m c c a Rth Y is presently Chief Curator at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art. Exhibitions he has organized or co-organized include Inspired Encounters: Women Artists and the Legacies of Modern Art (2022-23) the inaugural exhibition of the David Rockefeller Creative Arts Center in Tarrytown, NY; For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design (2019-22); and Women Artists in Paris, 1850-1900 (2017-18), awarded “Best Painting Show of 2018” by The Boston Globe. Prior to his work at the Westmoreland, he was Consulting Curator for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Curator at the National Academy of Design, and Associate Curator at the American Federation of Arts.

lsa m eha RY is an entrepreneur, creative director, and business-strategy coach for women-led businesses. She has a corporate background as an Art Director at T: The New York Times Style Magazine, InStyle, Real Simple, Harper's Bazaar, and Essence. Her design work centers on wellness, social impact for good, and interior design. She creates limited-edition product lines under the MeharyJewel brand for fun—and utilizes wellness travels for deep rest. She lives between Brooklyn and Mexico. You can follow her journey @elsalovesyou.

a nne kR aYB ill

Ben Jamin BR adY is a self-taught photographer and artist specializing in black-and-white photography. He has photographed for clients in Pittsburgh, New York City, London, and Mexico. Ben currently works as a photojournalist for Public Source

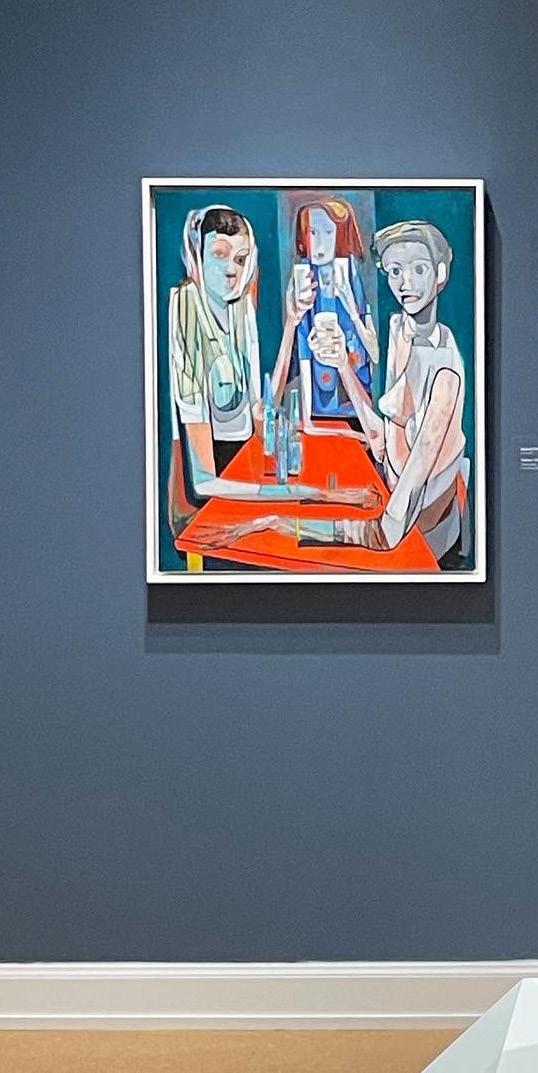

pamela coope R graduated from Seton Hill University with a B.A. in Graphic Arts/Fine Art and an Art Teaching Certification. She is an award-winning artist whose style is figurative, with abstract and expressionist influences. Pamela has exhibited throughout Pittsburgh, including at the Carnegie Museum of Art and the University of Pittsburgh Frick Art Gallery. Pamela’s work has also been featured at the Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba, in New York. She is a member of several Pittsburgh arts organizations and a resident of Greensburg, PA.

is the CEO of Art Bridges Foundation. Previously she was the Richard M. Scaife Director/CEO of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art. She implemented a new strategic plan which centers Diversity, Equity, Access, and Inclusion—and set the vision for the future, including an artist-in-residence program for BIPOC artists. Prior to her role at the Westmoreland, Anne was the Director of Education and Research in Learning at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

eR ika Butle R -Jones

is an interior designer, creative director, and cultural historian based in Pittsburgh, PA. An alumna of Harvard University (B.A.) and Parsons School of Design (M.A.), Erika creates work that dwells at the intersection of aesthetics, design, and Black cultural history. You can find her on Instagram @erikabutlerjones.

JacklY n monk

is Managing Editor of Editorial Operations at NewYorkPresbyterian Hospital. Prior to NYP, she was Managing Editor at WSJ., The Wall Street Journal Magazine

Jacklyn has been Executive Editor at Essence and InStyle, as well as Deputy Managing Editor at Real Simple. She has held senior staff positions at Vibe Girl, Bridal Guide, New Woman and Beauty Digest Jacklyn is also the Founder and CEO of Junebug Ink, an upscale greeting-card company that celebrates and commemorates modern life while uplifting AfricanAmerican culture, customs, and traditions. For more information, check out junebugink.com.

nina fR iedman

is originally from Boston, MA. She moved to Pittsburgh, PA, after completing her Bachelor’s Degree in Art History from the University of Vermont. Since then, Nina has held positions at the Andy Warhol Museum, Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Mattress Factory Museum of Contemporary Art. She has served as a board member of Bunker Projects since 2018 and is currently the board President. Nina is a second-year graduate student in the Arts Administration & Policy program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She will graduate in Spring 2023.

erica nuckles, Ph.D. (en): I started in my role here the same week you started thinking about this project, and Jeremiah has recently joined the Museum, so perhaps we can start with how the idea for this series first came to you?

gavin benjamin (gb): Years ago, some members of the museum came out to my studio in Pittsburgh. Eventually, the [now former] Director/CEO, Anne Kraybill, offered me a project with the museum. I saw it as a fabulous opportunity to create a completely new body of work. I wanted to create something longstanding to share with the community. Something that speaks about legacy, that tells the average person, I belong on these walls. I see me here. I was here. I see someone like me on these walls. And I belong. This sense of belonging has always been a part of me, since I was a child. I remember thinking the first time my friends and I drove through Westmoreland County on a visit to the museum: How do folks of color survive in communities like Greensburg around America? As an artist, a Black man, an immigrant, and a gay man, I can count the ways I don’t belong.

jeremiah William mccarthy (jWm):

Thinking about site, talk to us about what it was like shooting at the museum.

gb: It was an absolute honor to create this body of work within the space of the museum. Museums can be magical places for people to dream. Douglas Evans, the museum’s Director of Collections and Exhibition Management, took me into storage, the bowels of the ship, and I started to understand how the many pieces in the collection are connected. I’m an art geek who loves fashion and design. This was like shopping in the museum’s collections. It was priceless. It was the same feeling for me as shopping at Barneys on 17th Street in New York back in the day. Or seeing the Christmas windows along 5th Ave each year. These spaces are my design museums.

en: So how did you get it all done?

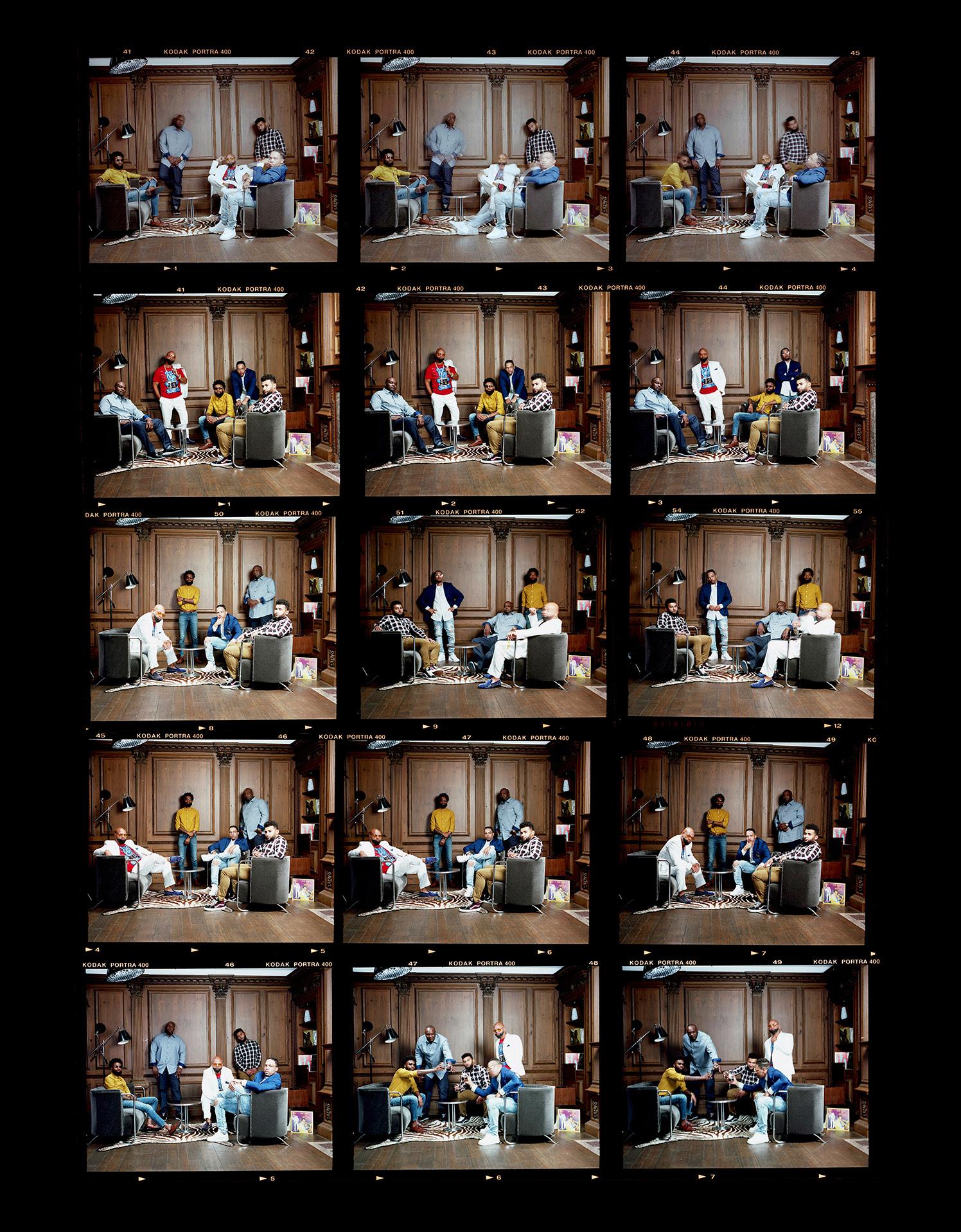

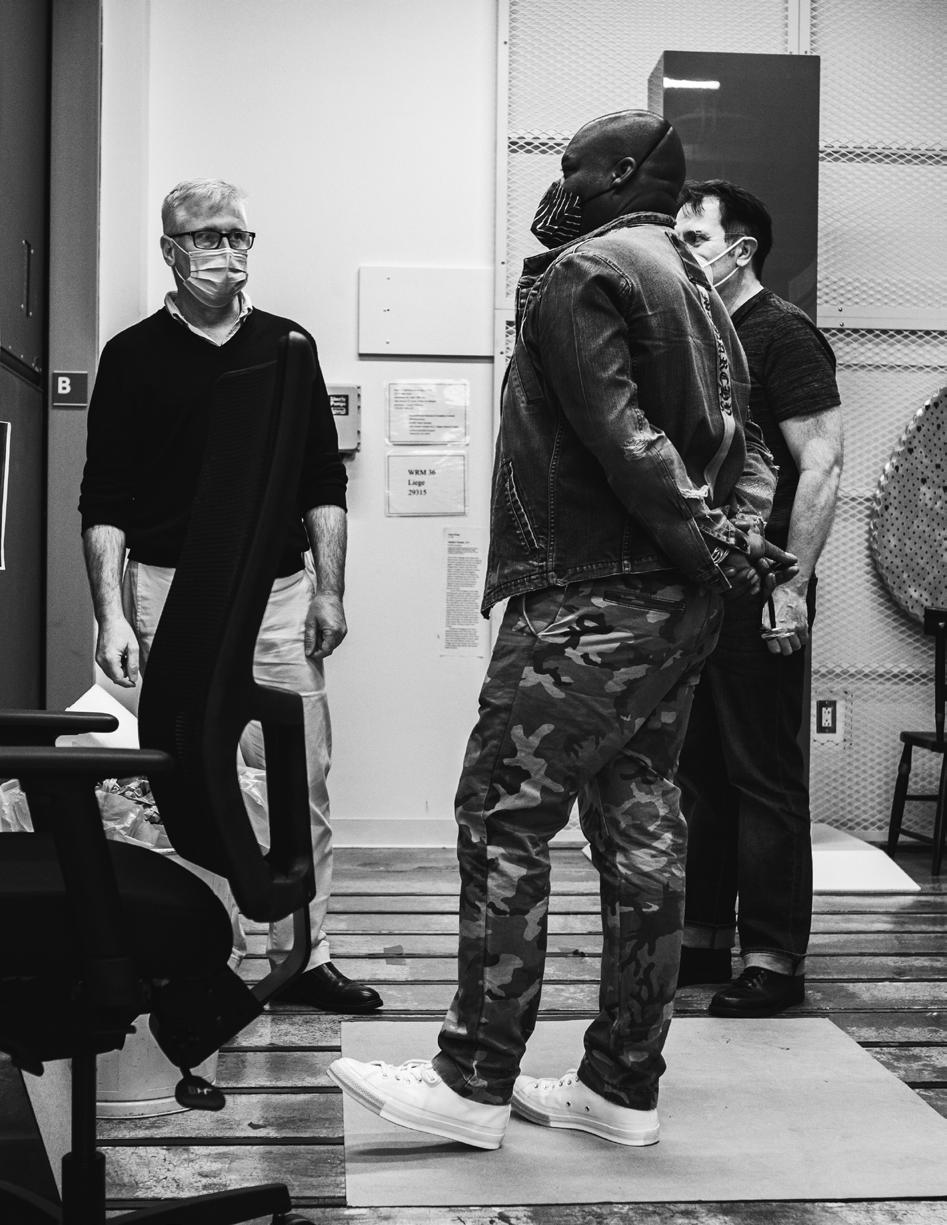

gb: This is a very big project. It was a collaboration and involved working with a team of creative people to help craft my vision for these narratives. Pamela Cooper, a native of Greensburg, was my casting director and community liaison. Michael Olijnyk, the former director of the Mattress Factory, aided with designing the many different sets. Ben Brady created a visual language for the behind-the-scenes, black-and-white shots. I think they have a rock and roll vibe. Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker Nick Childers made the documentary. And Nina Friedman, my project manager, managed to keep the train on the tracks.

jWm: I know you approach things in a very organized, very methodical way, with no time for nonsense. Did anything surprise you during this project?

gb: I was surprised by how embracing and welcoming the Westmoreland community was to this project. I realized early on as we were casting what impact this project might have on people’s lives, and the Museum came to see that, too. For many people within the community this is a way to be seen and heard. For some people I know, this would be the highlight of their life, to have their portrait hang in a museum. We as artists have the power to tell meaningful stories, engaging difficult narratives. Museums just have to be open to the world.

en: If you did this over, what would you change?

gb: I believe that each situation requires a different approach. Some of the things that were right for this project in Greensburg may not work for another city. One has to read the room and adjust, my mother would always say.

A white friend who grew up in g reensburg

s A id to me, ‘aR e the R e R eallY people of colo R in gR eens B u R g?’

I hope this project A nswers th At question.”

jWm: What is it that these photos accomplish that words cannot convey?

gb: Community and love are the words that describe what these photos accomplish. I believe we will be seeing and hearing about this project for a long time to come. I don’t want to underestimate the reach and potential impact projects like this might have on communities like Greensburg. I remember a white friend who grew up in Greensburg said to me, “Are there really people of color in Greensburg?” I hope this project answers that question.

en: You’re drawn to the fabulous. When did that begin?

gb: As a child, I spent a lot of time entertaining myself. Growing up in Brooklyn, my grandparents’ apartment was by Grand Army Plaza, across the street from the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, the Brooklyn Museum, and the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library. When most kids were outside playing, I was walking the gardens, looking around the museum, or borrowing books from the library. I was always curious, and the adults around me were busy with life, so they were just happy I was staying out of trouble. My family are immigrants from Guyana, once a British colony, who came to America in the 1970s. Life really changed once I started school in America. Kids right away let you know that you are an outsider. Museums, gardens, and libraries have always been the “safe” places. They are where you can dream and rest.

jWm: Who are your influences?

gb: The short answer is, there are so many and they are constantly evolving. After graduating from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, I went off to work for agencies that represented

photographers, directors, stylists, hair and make-up artists, etc. There I learned how to produce photo shoots for artists the agency represented. Some of those projects involved magazine clients— advertising and editorial. My influences at that point were based on the commercial side of the arts. These photographers, illustrators, and directors are working artists. I learned from them the craft and skill to produce projects on a grand scale, and how to stay on budget! I also learned how to keep up. Most of the time there were three to six projects going on at the same time. Eventually I became a freelance photo editor working for magazines. Then I was the one hiring the same photographers and artists whom I once worked for as a producer, the same people who taught me. It was amazing to close that circle of influence. I could elevate their work and use it to tell stories.

en: The title of this project references Nina Simone—why her and why this song?

gb: We were coming off of the pandemic, and I was spending a lot of time listening to Nina Simone, Ella, Louis, the Cole Porter songbooks, The Specials, Moby, and Massive Attack. It was also a dark time for me internally. Although I was incredibly grateful that I could still get into my studio, I was also mostly alone in Pittsburgh, so I focused on pushing my work and staying busy. Every time I heard Nina’s voice and those words, “Break down and let it all out,” there was this knife cut. I had to find a way to turn the visceral pain and anger of this song into something positive. Also, I was thinking about Nina’s role in the Civil Rights Movement.

jWm: What’s the first thing you would tell someone picking up a camera for the first time?

gb: For starters, I would immediately take

away their digital camera and give them a film camera, with 36 exposures, and tell them to go have fun. Make some pictures and come back. If they have only 36 images and they want to make them count, film changes the how, what, why. What is worth capturing? That’s what I’m thinking when I’m photographing with film.

en: How has photography changed you?

gb: Maybe ironically, photography has allowed me to see the world in shades of gray and not just black and white.

jWm: Describe to us your favorite photograph.

gb: To tell you the truth, there are just so many kinds. I want to say the hand of Miles Davis shot by Irving Penn. And his still lifes, and collaborations with designers like Issey Miyake. My favorites are timeless.

en: What might people take away from this project?

gb: Back in the day, as the story goes, information was passed down from village elders to children. This is my way of having that conversation—and providing a visual narrative to help advance this conversation. What do we carry forward, and what do we leave behind? American history is being rewritten today, by people who are afraid to have the real conversation of what it is like for a man of color to live in America now. This is my way of recontextualizing history and writing these missing pages and passages from our history.

jWm: And end this for us with a song lyric…

gb: “Birds flying high, you know how I feel…”

vie

from

All

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

…I can’t find anything positive to say.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

Yes! The Palace Theatre! Anywhere I was able to perform, and unapologetically express myself, holds a really special place in my heart.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum?

When I first visited the exhibit at the museum, I was joyful, emotional, and a little shocked. It was one of the very few times I felt seen and I felt as if I was a part of something larger than myself.

4. What Was the exPerience like, to sit for the Portraits?

Sitting, or as in my case posing, was at first nerve-racking. I didn’t know exactly how it was all gonna play out. I learned more about the project when I arrived, and Gavin supported and encouraged me during the journey. By the end I felt confident and very grateful for the moment.

5. What's one song/Poem/affirmation/hymn everyone shoulD knoW?

Song: “Special,” by Lizzo

Affirmation: “Take a deep breath. It’s just a bad day, not a bad life.”

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD?

Surprisingly, I didn’t go to museums as a kid, and really not even now, into my adult life. I was never very intrigued by art until the last two years of my life. As I’ve grown, I found that art of any form has become something that I’m constantly seeking.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

Museums don’t mean much to me, but they do represent something to me. They represent so many facets of life, which is what I find intriguing. You can go to a museum and explore many different walks of life. Museums have the possibility to challenge the way you see and think about yourself and the world around you.

8. What WorD best Describes your style?

Authentic.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD?

One hundred percent, I most certainly do. Art inspires. Art creates community. Art sparks conversation. Art heals. Most importantly, art is a global language.

10. What is one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience?

One thing I will take away from this experience is that it’s okay to be unapologetically me. Not just me, but every single part of me. I am a gay, Black, feminine, male-identifying person. Those things do and are allowed to coexist, in any form or fashion. That by itself is art!

BY eR ika Butle R -Jones

To walk through Gavin Benjamin’s latest work, Break Down and Let It All Out, is to experience a quiet, evocative portrayal of what many may consider to be traditional themes. But it would be a mistake to overlook or underestimate the complexities at play—for this work is, at once, both a celebratory repositioning and a radical reimagining of Black life in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Presented at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg—a quaint, rural suburb 30 miles east of Pittsburgh— Break Down and Let It All Out spans three adjacent exhibition spaces in the museum and is primarily situated within two areas, known collectively as the Paneled Rooms.

An architectural donation to the museum in 1966, the Large and Small Paneled Rooms were originally part of a historic English home and were designed by Sir William Chambers, the noted Swedish-Scottish architect who served as architect to King George III of England in the second half of the 18th century.

Boasting intricate ornamental detailing, including wainscoting and other decorative trim work, the Paneled Rooms’ walls and ceilings are indicative of Chambers’s neo-classical style. These elements fill the space with the storied stateliness of European classical revival architecture, which also inherently conjures up images of the kinds of people who originally commissioned and inhabited these spaces: wealthy, often royal, white men.

And in this requisite conjuring, these architectural signifiers also simultaneously—though often, but not always, quietly or indirectly—connote the kinds of people for whom these spaces were neither commissioned nor intended, at least as anything other than servants, that is: Black people, Brown people and other people of color.

These Paneled Rooms, constructed around 1750—when Pennsylvania itself was a British, slaveholding colony—are steeped in the history of British colonialism. Now, residing in Westmoreland County, they are located in a region whose state representatives, in 1780, voted against the passing of Pennsylvania’s Gradual Abolition Act, where slave auctions continued to be held until 1817.

These, then, are the spaces and context that serve as the backdrop for Break Down and Let It All Out. This specific architectural

setting offers a direct, material connection to America’s colonial roots and to its resulting racial and socioeconomic hierarchies. Furthermore, this backdrop proves even more pertinent when one considers the concept behind the exhibit's installation.

In Break Down and Let It All Out, Benjamin reimagines this historically complex backdrop as the home of a fictional Black family; a home which, in the context of this work, the family has owned for nearly 250 years. In so doing, Benjamin positions the present-day subjects of this work as descendants of these imagined free, Black Americans, who would have possessed a heritage of freedom and relative autonomy that dates back to before America’s own independence from Great Britain.

And to embody this idealized legacy, Benjamin chose local Greensburg and Westmoreland County residents to serve as the subjects of his portraiture—a choice that elevates these residents both figuratively and literally, to the physical extent of these images being mounted on the walls of the museum—which, in architecture, are known as a space’s “elevations.”

Within the exhibition space, the resonance of these artistic and subject-based choices is acutely palpable. Whether it is Shirlene, whose portrait hangs over the fireplace of the Small Paneled Room, adorned in a vibrant tunic and captured by the lens in a state of joyous movement, or Anthony and Angela, who stare lovingly into each other’s eyes in the Large Paneled Room—this is a work of collective, celebratory re-contextualization.

Thus, in its repositioning of Black Westmoreland County residents as the subjects of this work, Break Down and Let It All Out effectively breaks new ground while drawing historical connections. And it does so in a multilayered way: both within the immediate context of the individuals and families who are now prominently featured in the museum’s gallery, and within the macro context of the larger historical tapestry that this work is now woven into.

And as Nina Simone sings in “Break Down and Let It All Out” (1966), the song from which Benjamin’s exhibit derives its name, perhaps it is this kind of radical re-imagining of Black subject-hood and proprietorship that will allow new “old memories” to aid in eventually setting our collective hearts at ease.

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

I live in the suburbs of Greensburg, and I think that people in this area are way behind the times.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

I like to hang out in my bedroom, where I play video games with some friends online and hang out with my dogs, Darth Vader, Princess Leia, and Ahsoka. Yes, I am a big Star Wars fan. I’m also into collecting comics. I work with DDC (Disabled Developmentally Challenged) Adults. I like helping DDC people because I know I am making a difference in their lives.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum? When I saw myself on the wall, I thought, This is so surreal. I never actually thought of myself like this.

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits?

Well, when my mom told me that she wanted me to wear this outfit and do this modeling thing…I was like, Nah. But she said I would get paid, so how could I say no? l think my dogs were kind of freaked at first. They were in a different environment. Gavin made us feel comfortable, and it was a really cool experience.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/hymn everyone shoulD knoW? I really don’t have a song or poem I look to.

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD? Yes. Me and my mom used to go at times.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

For me, a museum is a place where I can go to look at art. It is quiet there, and I can be at peace with my thoughts. I will sometimes go by myself to a show and then come back with a friend and ask them to tell me what they see.

8. What WorD best Describes your style?

I am kind of a laid-back kind of guy. I dress for comfort and not really flashy. My mom always likes for me to get dressed up and come to openings with her. I do sometimes, and I guess I kind of like to dress up at times, but I would much rather be in my jeans and sweats.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD? Most definitely. Art is a language in itself.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience? Being a part of history.

(Featured in the previous spread, in the forefront.)

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

Westmoreland County is a quiet, safe place to live. It is good for older people and children. The population is about 354,663: 93.5% White and 2.3% African American.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why? My church, Greater Parkview Church in Greensburg. Families and friends gather to worship together and to serve others in the community.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum? It was an amazing experience. It was an emotional experience. I have great admiration and appreciation for Gavin Benjamin. His work is outstanding.

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits? It was exciting. It was magical. The care, attention to detail, and professionalism that was taken to bring this project to life. It was like a dream.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/hymn everyone shoulD knoW? Philippians 3:13, Brethren, I count not myself to have apprehended; but this one thing I do, forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before.

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD? I did not. I grew up during the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. However, in the ‘70s, I did take my son to Pittsburgh on the weekends to visit museums for cultural experiences. I worked with the NAACP Youth Council over the years. We visited the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum in Baltimore, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Museum in Cincinnati, the Smithsonian Museums in Washington, DC, and most recently the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC.

7. What Do museums mean to you? Museums afford learning opportunities and preserve history.

8. What WorD best Describes your style? Sophisticated.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD? Yes, perspectives can change through education and greater understanding. Art inspires. Art is thought-provoking.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience? Gratefulness for the Westmoreland Museum of American Art and for Gavin Benjamin undertaking this great project, highlighting people of color in Westmoreland County.

w estmorel A nd county is A quiet, sA fe pl Ace to live. It is good for older people A nd children. t he population total is a B out 354,663. 93.5% a R e white and 2.3% a R e a f R ican a me R ican.” — R uth

R eg and matthew, Je A nnette, PA

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

Greensburg is a hidden gem that is a walkable, small college town with a close-knit family feel. If you mention one or two family names, it is likely that one in five of the people you meet will be related to one of those families.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

I have a special fondness for Linn Run State Park and the Conemaugh River, because a friend introduced me to the joy and mental-health benefits of enjoying nature through hiking and kayaking. I also enjoy visiting the city of Connellsville, PA. It is one of the most welcoming and diverse areas that I have experienced since moving here.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum?

I am so proud of this work! Because I honestly do not like taking pictures. When I saw the finished results, I called people close to me and told them that I am “literally a work of art” that you can visit in a museum!

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits?

I was a little nervous, because I wanted to be a good subject for Gavin. He made me feel comfortable and empowered. I had fun. I embraced it as my moment in history.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/hymn everyone shoulD knoW?

I actually have two: a quote and a poem.

The quote is:

“Once you know who you are, you don’t have to worry anymore.”

~Nikki Giovanni

The poem is “Dreams” by Langston Hughes:

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field Frozen with snow.

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD?

We went to museums as part of school trips but never as an intentional family outing. My parents worked a lot. What free time we had was filled with intention for survival.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

I have a greater appreciation of them now, as an adult. They hold so many treasures that reflect the past, present, and future in the most objective, diverse, and beautiful ways. I don’t know of any other institution that does this job as well.

8. What WorD best Describes your style? Eclectic.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD?

I think art is a reflection of all the emotions, thoughts, realities, and views that we struggle to verbalize but desire to express. Art helps capture our innermost complexities and vulnerabilities, then displays them for the world to see. When we encounter art that stirs, excites, touches, puzzles, or even frightens us, I feel that piece of art has done its job. It unknowingly becomes a seed in the beholder’s consciousness that eventually blooms in its own time.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience?

I have to say that nothing beautiful is created in a vacuum, or by one individual or one moment; it takes a well-choreographed kaleidoscope of talent, timing, and temperament to make the most complex work seem effortless.

c

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

I would describe my community as vibrant and active. Its members are engaged in efforts that promote the neighborhood in ways that they believe are productive. Although this participation is not always uniform or universal in its underlying beliefs, members of my community are passionate about their identities.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

As a career educator, for me, the classroom is always a special place. I do my best work in the classroom: I build dreams. I encourage hope. I advocate for change.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum?

Gavin Benjamin is truly incredible! In experiencing his art, we are all charged to consider and reconsider the meaning of community on multiple levels. I am proud to be a part of that transformation for so many people.

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits?

In Fall 2020, I lost both of my parents to COVID-19. Two years later, there is still no day that I do not mourn my parents. Given the restrictions in in-person gathering, my sister and I were unable to hold traditional funeral services. It crushed me that my parents were unable to have the homegoing that would celebrate their extraordinary lives. Unsurprisingly, it gave me pause to sit for a portrait where I would be reenacting events from the most devastating period of my life. However, in some way, the experience comforted me. As I lay portraying a “dying” model for the portrait, I felt an overwhelming sense of peace. I believe I was led to be a part of this work. It’s almost a reassurance that my parents are safe and watching over me.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/ hymn everyone shoulD knoW?

Maya Angelou is famous for this quote: “Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better.” While not a poem or a verse, these words always give me hope that a better world is yet to come. I know that some

days I am very successful, but there are other times when I fall short of my goals. Regardless, each day is an opportunity to improve and grow. If we all would learn to live by this sentiment, imagine what we would be able to accomplish as a society.

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD?

I went to the Carnegie Museum of Art often as a child. I had art-appreciation classes in grade school that would direct me to seeing special exhibits and shows at the museum. I would beg my parents to take me for visits so I could be a part of the experience.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

Museums are a wonderful, low-cost way to develop skills of perspective-sharing and empathy. Each person views art differently. Our interpretations can tell others so much about ourselves and how we understand the world around us.

8. What WorD best Describes your style?

I would like to think of my style as classic. I appreciate a clean, polished look for myself. For better or for worse, I think many people still continue to judge others by what they wear. I work in a position where it is important to gain the respect of colleagues and those I supervise. Consequently, I select modest, professional clothing so others will see me as serious and focused.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD?

Absolutely! I think art makes us all more kind and gentle. Art encourages us to look at the faults of the world critically. Yet the beauty of art softens the injustices of the world, so that they become palpable to society, leading us to identify pathways to effect change genuinely.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience?

Although I have always had an appreciation for art, I never considered “everyday” people as part of it. I am grateful for this experience. It has encouraged me to reflect on the beauty that is inside us all.

I h Ave A lwAys h A d A n A ppreci Ation for A rt, but I never considered ‘everydAy’ people A s pA rt of it. I am g R ateful fo R this expe R ience B ecause it encou R aged me to R eflect on the B eaut Y that is inside us all.” —t R icia

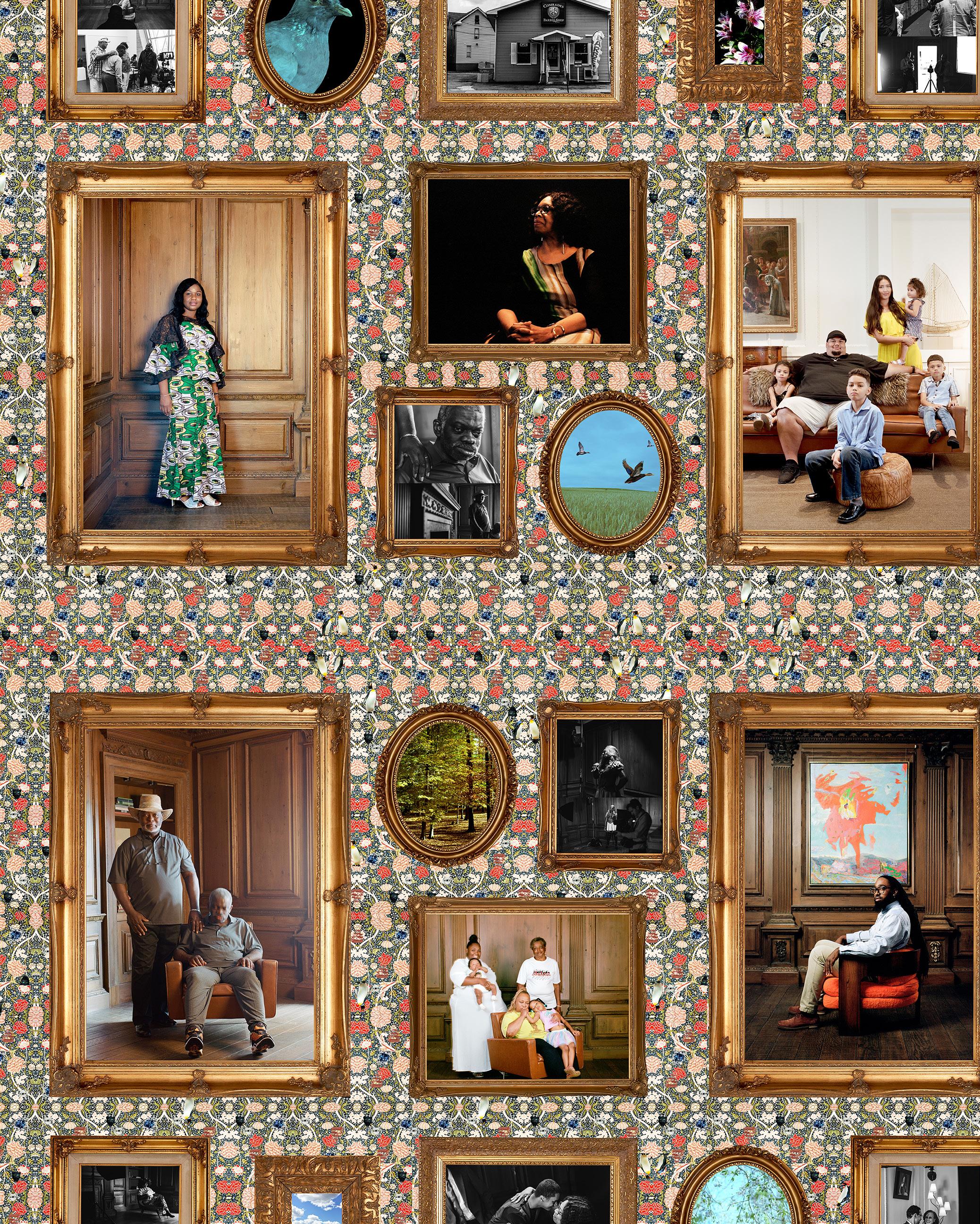

b ecause gallery s Pace Was extremely limite D, this Wall Pa P er Was custom- D esigne D for the Break Down and Let It All Out exhibition, ex Pan D ing the number of P ortraits inclu D e D.

Gavin Benjamin’s photography offers hope for an equal and just future, in a present shaped by oppression and outrageous neglect.

BY ta R a faY coleman

When I relocated from Buffalo to Pittsburgh, back in 2004, I had no knowledge of the existent historical connections between the two cities, and therefore considered myself an outsider in many ways. The Rust Belt refers to a geographical region comprising Chicago, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Detroit (among other cities) that once served as a hub of industry where coal and steel thrived. Now I know: I am and always have been a granddaughter of steel mills, and Pittsburgh is as much a part of my history as Buffalo ever was. There’s a sense of pride that comes along with knowing you belong somewhere, that you are as much a part of the history, and a part of the narrative, as anyone else.

As Black people, to see ourselves in something is to be recognized and accepted. This need is rooted in an innate desire for connection, and our hope to be known and validated within spaces where we have traditionally been ignored. To see is to be seen, and there is a particular urgency to be seen as a Black woman in Pittsburgh, where the conditions of a decent life are not guaranteed for many of us. We are often represented in ways that lack perspective, or represent a singular outlook or experience—narrow representations of Blackness that don’t reflect the nuances of what it is to actually be an African American living in a Rust Belt city.

It’s rare that I'm able to see myself in the work of many artists. What most often seems to be cast back are only bits and pieces of me; a glimmer or a fragment of something familiar, the work serving as a requiem for a memory or experience that’s not quite whole, not quite my own. Gavin Benjamin’s Break Down and Let It All Out (2022) at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art presents a body of work that focuses on individuals and communities, while critically addressing an institution that has historically excluded them. Benjamin documents subjects with grace, intention, and dignity, and challenges the rigid constraints that exist within traditional modes of portraiture.

In this exhibition, the bits and pieces of myself that I see have created something robust. The formal beauty in the images creates a sense of pride and inspiration; the Blackness displayed here is both visible and aspirational. Benjamin’s photography frames his subjects as historical figures while allowing space for them to show up as themselves, acknowledging the depth and varied experience of Black people in Westmoreland County. In an approach that echoes life stages, legacy, and parenthood, they are multi-generational. There is vitality, joy, and humanity on display, giving us hope for a future in a present shaped by oppression and outrageous neglect. Here, we belong. We are a part of the history and the narrative. Here, we are seen and heard. Here, we have commanded the space and created a visual record of what it is to be Black in a Rust Belt city.

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

The City of Jeannette was once an industrial hub of Southwestern Pennsylvania, in the early 1900s. With industry and factories leaving the area and most of the United States, it is much smaller now and barely surviving. It is trying to find and reinvent its new identity, although many have given up on it and regard it as a “dead town.” Jeannette has always been considered an “underdog,” but the people have great pride, a strong spirit, and competitiveness.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

I regard Jeannette as special to me. I had a WONDERFUL childhood growing up here. Many, many people feel the same way. I regard my grandmother’s and mother’s homes as sacred. They have passed away, and those [homes] are the last signs of their existence and accomplishments of their time on this planet.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum?

Like an honor. It gives a feeling of accomplishment. But, knowing that [the exhibition] is most likely only temporary leaves a feeling that there will be regression and loss. And once again, less representation of African Americans in the county and community.

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits?

It was a great experience. I’m very proud to have been able to do it and contribute.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/hymn everyone shoulD knoW?

I have none, in particular, but I would say to anyone “The one that brings YOU a positive feeling and mindset of hope and joy,” which is so much needed, every day.

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD?

Maybe once or a few times, as a kid, possibly as a school field trip. But I only REALLY remember museums as I began college at the University of Pittsburgh and went to the Carnegie Museum of Art, and others in Pittsburgh.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

A recording of history and [certain] individual’s creativity and thoughts on society...whether realistic or abstract.

8. What WorD best Describes your style?

Mine. Diverse.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD? Absolutely. It leaves room and possibility for people to use their own minds and creativity, to tell the story that the art portrays. It allows room for open conversation and discussion.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience?

A moment of accomplishment.

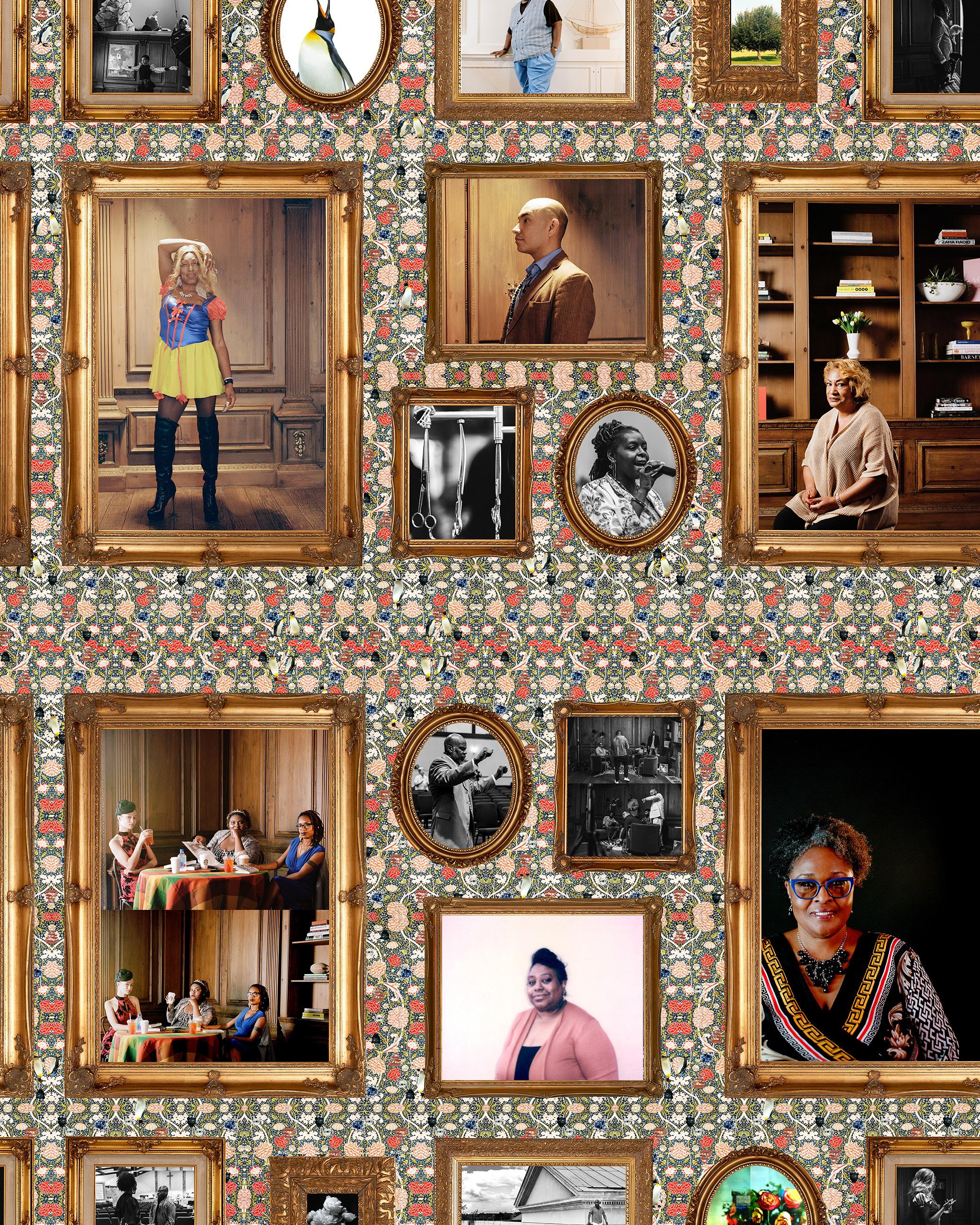

Installation vie W, Break Down and Let It All Out , at the Westmorelan D m useum of amer I can a rt. b enjamin’s P iece, on right Wall, Was ma D e in D irect conversation W ith the P iece from the Westmorelan D’s collection.

J ohnnie, Je A nnette, PA

1. hoW WoulD you Describe Where you live?

I live in the county seat of Westmoreland County, Greensburg, and I reside in Hempfield Township. I live in a modest house in the township.

2. Is there a Place that is sacreD or sPecial to you, anD Why?

Besides my home, I love to sit on a high hill and see as far as I can see. In addition, I enjoy church and visiting my grandparent’s home in Leechburg.

3. hoW Does it feel to see yourself on the Walls of the museum?

I was honored to see my picture there with so many others. It was a treat to see so many Black individuals pictured in such an honored place. The only other times I saw this many Black people was at the Tennie Harris display at the Greensburg Museum.

4. What Was the exPerience like to sit for the Portraits?

Sitting for the portrait was exciting and fulfilling. The artist was great and eased all fears about being photographed.

5. What’s the one song/Poem/scriPture/hymn everyone shoulD knoW?

My Song is “Amazing Grace.”

When it comes to poetry…anything by Maya Angelou.

My favorite scripture is Psalm 23.

My Hymn is “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.”

6. DiD you go to museums When you Were a kiD?

Yes, in school we toured the Carnegie Museum of Art. It was exciting and awesome.

7. What Do museums mean to you?

History. I always say: “You don’t know what you can do until you know what you have done.” I have been to the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture, in Baltimore, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. Both institutions are inspirational and thought-provoking.

8. What WorD best Describes your style? Classic.

9. Do you think that art can change hoW PeoPle think or look at the WorlD?

Yes, by all means. They say a picture is worth a thousand words and a song can melt the cruelest heart.

10. What is the one thing you Will take aWay from this exPerience?

Joy from the entire experience. This exhibit has many people talking about the people of Westmoreland.

It's not enough just to remember . . .

The psychologically rich portraits that make up Break Down and Let It All Out envision a lush living space inhabited by a fictional Black family for almost 250 years.

BY Je R emiah w illiam m cc a Rth Y

Kellie, reticent smile and side-swept hair, crouches in the corner of an empty room. Anthony and Angela, side-byside with interlocked gazes and hands, create a world unto themselves, in a room already peppered with pairs. Ty, both weary and self-possessed amidst the heavy symbols around him, reclines in a chair. The portraits themselves tell stories.

Initially aiming to connect with the African-American residents of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Gavin Benjamin invited numerous members of communities historically underserved by institutions—recent immigrants, firstgeneration Americans, and POC—to sit for portraits and imagine their places within the Westmoreland Museum of American Art. Kellie is from Greensburg, Anthony and Angela from Plum, Ty from Jeannette.

The portraits are set in two stately paneled rooms, built circa 1750, designed by Swedish-Scottish architect Sir William Chambers, and donated to the Museum by Mrs. Cordelia Scaife May and Mr. Richard M. Scaife in 1966. The museum’s footprint was expanded to accommodate the rooms, which once graced Penguin Court, the Scaife family estate, named for the 10 penguins that once roamed the property. Museums, like estates, are sites of enormous power and privilege—and within the Westmoreland Museum, a space composed of cantilevered galleries and cubes, the paneled rooms are a potent testament to institutional power. As the inaugural project of the Museum’s new series of paneled-room projects, Break Down and Let It All Out acknowledges the museum’s complex past, visualizes possibilities for the present, and gestures toward a more equitable future.

The exhibition is conceived as a fantasy. Moving through the paneled rooms, a visitor finds objects from the museum’s collection installed alongside Benjamin’s psychologically rich portraits of the surrounding community. Their combined effect creates a fabricated domestic space that has been occupied by a fictional Black family for nearly 250 years.

Certain visual motifs echo across media; boats populate both the photographs and the rooms, taking various incarnations, ranging from vanessa german’s assemblage to the vintage pond model of the 1940s—the “Sail-R-Boy” Challenger. These vessels allude to migration and travel, stories of pain and possibility. Elders adorn the walls, from Robert Gwathmey’s Portrait of a Black Woman (1949) to Benjamin’s Yvonne, Greensburg, PA (2022). Their roles in the preservation and transmission of knowledge are symbolized in Harry Roseland’s A Stitch in Time (n.d.), which crowns the large paneled room’s mantle, a tender depiction of a grandfather and granddaughter meticulously sewing a button.

Questions begin to form in the mind: How might we think otherwise about sites of power and privilege? What role does a museum play in the formation of a community? And how do portraits both preserve and provoke? Just as photography has the power to turn people into objects, photographs can also take on lives of their own. They are powerful tools for imagining alternatives to the present—and play a transformative role in the formation of cultural memory. Nina Simone once sang, “But it’s not enough just to remember, ‘cause/ What good is the past?” Look closely. Break Down and Let It All Out might offer an answer.

l et it a ll o ut

Determined to meet the BIPOC community of Westmoreland County, Gavin Benjamin enlisted the assistance of a local, well-known artist who helped him connect with all the right people and forge genuine friendships.

BY pamela coope R

In the Spring of 2021, I received a call informing me that Pittsburgh-based artist Gavin Benjamin needed models for his residency at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art. I saw Benjamin standing outside the museum, engaging with prospective sitters. I was immediately drawn to his smile, his energy, and the warmth he generated. After I spoke with him, he asked me to assist him with the project. As I learned more about his overall vision, we worked together to develop what eventually became Break Down and Let It All Out

I am a well-known Greensburg artist and resident, and Benjamin wanted me to introduce him to some of the BIPOC residents of Westmoreland County. He wanted to feature locals as subjects in a new body of work that would be displayed at the museum. Because I knew it would be a challenge for him to meet people without my assistance, I became Benjamin’s casting director, introducing him to a great number of people reflected in the outcome of the final project. As a fellow artist, I shared some of Greensburg’s colorful history, including my life here as an AfricanAmerican female artist.

I told Benjamin that he should go to places where BIPOC people gather, and I cataloged each encounter, including dinner at a fellow artist and friend’s home; a Saturday-morning mass at the Living Word Congregational Church; and a busy afternoon visit to Comrades Barber Shop, located in Greensburg. During each visit I introduced Benjamin to my community. All were eager to participate in his photoshoot at the museum. I suggested he show the documentation to the former Museum Director/CEO Anne Kraybill, in order to provide a more comprehensive framework of his vision.

As an intermediary, I was responsible for conveying Benjamin’s overall goal to the participants. Watching each phase of the process unfold brought me unexpected excitement in my own capacity as an artist, as I was able to witness the power of community bringing this project to life.

This photographic exhibition presented an opportunity to introduce audiences to multiculturalism in art and community, while creatively highlighting natives within the local narrative. I appreciate the unique opportunity to be a part of Break Down and Let It All Out. I hope the museum will continue to support diverse aesthetics featuring Pennsylvania BIPOC artists and collaborators.

paneled R oom 5 6 4 7 3 8 2 9 1

1. Gavin Benjamin, Derby, Tonyia, N-Dia, Greensburg, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

2. Gavin Benjamin, Kellie, Greensburg, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

3. Nick Childers, director, Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let It All Out, 2022; Daymon Long, editor; documentary film

4. Gavin Benjamin, Cynsere, Jeannette, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

5. Gavin Benjamin, Comrades Barbershop, Jeannette, PA; Transparency film in lightbox

6. John Talbott Donoghue, Young Sophocles with his Lyre, around 1889; Patinated bronze; Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland, 2015.111

7. Gavin Benjamin, Shirlene, Greensburg, PA, 2021; Transparency film in lightbox

8. Malvina Hoffman, La frileuse [Woman in the Cold], 1912; Bronze; Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland, 2015.114

9. Gavin Benjamin, Kyle, Greensburg, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

Additional photographs from this exhibition, created by Gavin Benjamin in direct response to the Museum’s artworks, are placed throughout the permanent collection galleries.

Gavin Benjamin’s photographs for this exhibition are from the series Museum Pictures, 2021; courtesy of the artist; © Gavin Benjamin

1. Mickalene Thomas, Shug Kisses Celie, 2016; Silkscreen, ink, acrylic on acrylic mirror mounted on wood panel; Legacy gift selected by Judith Hansen O’Toole. Funding provided by The Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation in honor of her 25 years as Director/CEO, 2018.19

2. Gavin Benjamin, Doris and Ron, Latrobe, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

3. Robert Gwathmey, Portrait of a Black Woman, 1946; Silkscreen on board; Gift of Mrs. Sunny Pickering, 1993.22 Bruce & Sheryl Wolf Interactive Space

4. Harry Roseland, A Stitch in Time (Sewing on a Button), undated; Oil on canvas; Gift of Mr. Richard M. Scaife, 2013.6

5. Grace Helen Talbot, The Slave 1924; Patinated bronze; Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland, 2018.87

6. Ben Shahn, Byzantine Isometric, 1951; Tempera on canvas mounted on masonite; Museum Purchase, 2007.21

7. Gavin Benjamin, Larry and Veronica, Jeannette, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

8. Gavin Benjamin, Ty, Jeannette, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

9. Gavin Benjamin, No. 05, from the series Heads of State, 2020; Mixed media collage on canvas

10. Adolph Weinman, Rising Day, around 1915; Patinated bronze; Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland, 2015.119

11. Vanessa German, Parade to the Baptism, 2013; Mixed media; Museum Purchase, 2014.3

12. Adolph Weinman, Descending Night around 1915; Patinated bronze; Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland, 2015.118

13. Gavin Benjamin, No. 11, from the series Heads of State 2020; Mixed media collage on canvas

14. Gavin Benjamin, Anthony and Angela, Plum, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

15. Agnes Weinrich, Lady Slippers in a Vase undated; Oil on board; Museum Purchase, 2007.11

16. Maker Unknown, Schooner with Cloth Sails, undated; Painted wood, metal, cloth; Museum Purchase, 1986.64

17. Gavin Benjamin, Living Word Congregational Church, Jeannette, PA, 2021; Triptych; Varnished archival pigment print

18. Maker Unknown, Federal Swell-Front Sideboard, around 1820; Wood with inlaid Mahogany; Gift of Elizabeth Braun and the Ernst Estate by Exchange, 1990.36

19. Maker Unknown, “Sail-R-Boy” Challenger Sailboat, 1940s; Wood, metal, cloth; Gift of the Friends of the Museum, 1984.112

20. Maker Unknown, Sailboat, undated; Painted wood, metal, cloth; Museum Purchase, 1974.134

21. Jacob Lawrence, Worker with Tools, 1997; Crayon on paper; Museum Purchase through the Thomas Lynch Fund and the William W. Jamison II Art Acquisition Fund, 2006.12

22. Gavin Benjamin, Yvonne, Greensburg, PA, 2021; Varnished archival pigment print

t he w estmo R eland m useum of ame R ican aR t, gR eens B u R g, pa I spent four months in residence at the museum, exploring its collection and inviting community members inside the museum to sit for their portraits. Many of these Black and immigrant community members had never been inside the museum.

On my third day of hosting casting sessions at the museum, I met Pamela Cooper, a local artist and activist. I told Pamela I was disappointed that more people had not shown up to the session. She told me: “Honey, our people are not going to come to you.” That’s when I understood I needed to go to them. These are the Polaroids from those sessions.

For the photo sessions, I planned to build an elaborate set with beautiful furniture and fixtures that evoked opulence and grandeur. Michael Olijnyk is an avid antique-furniture collector who has a fascinating loft on Pittsburgh’s Northside. It is filled with the kind of objects I needed. To my surprise, when I reached out to Michael to ask him about borrowing his furniture for my shoot, he said, “Yes!” With his incredible eye for design and architecture, he really helped bring my creative vision to life.

Being given total access to the museum’s collection was a dream come true. There are so many objects that the public never gets to see and that span a great range of history and styles. Doug Evans, Director of Collections and Exhibition Management, walked me through the treasure trove, showing me many hidden gems and highlights. It was important for me to have this experience. Because of it, I was able to connect with different pieces, form my own narratives, and then add them to the exhibit.

In African-American communities, the barbershop is not only a place for men of all ages to get their hair cut but often a safe space for them to gather. It is social, lively, and a place to be your authentic self. It was important for me to go here, because I wanted to connect with the community in their own spaces. There was no other way. These barbers are artists. One of them even went to school for graphic design—and it totally shows up in his haircuts.

Meeting members of the Living World Congregational Church felt like coming home. It was especially poignant to be there during the pandemic, when churches had been contentious sites of viral transmission. The community lost several people to the pandemic and was still grappling with its grief. The church is so central to the community, as it provides many services our government fails to deliver: babysitting services, after-school programs, and financial assistance to those in need. But most of all, the Church provides a place where souls can find peace and rest.

Over the course of several days, I took the portraits of over 70 community members. They all showed up with their own style, which was fabulous. For some of these folks, it was their first time visiting the museum. I made it my job to make them feel welcome and to show them that they belong here. In the end, I was overjoyed for them to see themselves on the walls.