Vol. 4

Vol. 4

March 17, 2025

The works of Salem Al-Qudwa, Rania Qawasma, and Rana Abughannam highlight architecture’s role in Palestinian resistance, resilience, and participatory design. While their focuses vary—Al-Qudwa on post-war reconstruction, Qawasma on participatory storytelling, and Abughannam on education and heritage—they share a commitment to communitydriven design and the integration of social and physical space as a tool for resistance.

“...engage communities in the rebuilding process to empower them.”

- Salem Al-Qudwa

Al-Qudwa emphasizes small, everyday acts of rebuilding that reinforce belonging, advocating for reconstruction that aligns with socio-cultural practices. Qawasma critiques individualistic architectural approaches, urging participatory design that preserves collective memory and identity. Abughannam expands on these ideas by exploring how education adapts under oppression, reinforcing that learning spaces are also sites of resistance.

Together, they argue that architecture in Palestine is more than physical reconstruction—it is a means of reclaiming space, preserving identity, and empowering communities. Rather than serving as external symbols of progress, architectural interventions must actively contribute to the wellbeing of those they are meant to serve.

is an architectural engineer with extensive experience in reconstruction and shelter projects in Gaza. His work aims to establish affordable designs for ordinary people while engaging local communities in the building process (Framer Framed). Holding a Bachelor of Architecture and Master of Architecture from the Islamic University of Gaza, as well as a PhD in Design from Oxford Brookes University, Al-Qudwa specializes in creating housing solutions that align with their socio-cultural practices and utilize efficient resources. His approach is rooted in self-help housing that re-purposes existing materials to provide vital support for affected communities.

In Al-Qudwa’s lecture The Reconstruction of Everyday Architecture in Gaza, emphasized the importance of making connections between social and physical aspects when rebuilding efforts. He highlighted the need to approach case by case, ensuring that reconstruction efforts reflect

the identity of the community that creates a sense of dignity and ownership. Al-Qudwa advocates to engage communities in the rebuilding process to empower them.

He noted that even small acts, such as people taking part in planting trees, contribute to rebuilding efforts and foster a sense of belonging. He used sketches and diagrams to engage with families, translating their needs into architectural solutions. His emphasis on a caseby-case, home-by-home approach underscored the different ways families, particularly women, utilize space – highlighting how activities like bread-making serve both familial and communal roles. He explained how “Architects tend to think architecture matters. Not everyone else does. To many people, buildings are expensive but very interesting. It’s what goes on inside them that matters,” stressing that meaningful reconstruction is about more than just physical structures. By actively involving communities in the process, Al-Qudwa’s approach fosters empowerment, dignity, and a true sense of ownership over their homes.

“Maybe architectural design might not solve the entire problem, but it can contribute to solving part of it.”

Through his work, Salem Al-Qudwa has proposed and implemented design elements that acknowledge the constraints of everyday life while striving to create more imaginative and functional spaces for widowed women and families. Sara Roy, an American political economist and Research Associate at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University, remarked that “Palestinian development has never really been a Palestinian project, but an Israeli and American one reflecting only the interests and priorities of the latter. Salem’s research directly challenges this…” By actively involving the community in the development process, his work ensures that solutions emerge from lived experiences rather than external agendas. He concludes his presentation with an important note: “Maybe architectural design might not solve the entire problem, but it can contribute to solving part of it.”

Rania Qawasma is a community architect and founder of DAARNA, an organization that provides forcibly displaced and uprooted people with a healthy, safe, and nurturing place to call home. A new organization, From Isolated to Organized, shares similar values and hosted a lecture on Sunday, February 23, where Qawasma spoke about her family’s history in Palestine and the enduring impact of the Israeli occupation. She emphasized that architecture goes “beyond the physical space.”

Qawasma stressed that architects and designers are deeply intertwined with identity, culture, and history, urging them to see their work as more than just a profession. “You can’t separate design practice from the meaning of the place.” Architecture is not merely about buildings or physical structures—it embodies collective memory, land, and the stories of people. Her work highlights the power of participatory design and storytelling, encouraging architects to use their practice as a means of resisting injustice and displacement.

“You can’t separate design practice from the meaning of the place.”

She shared her experiences engaging with refugees in workshops where they designed their homes that reflected their values and cultural roots. In one example, children incorporated elements from their homes into their artwork, illustrating cultural connections they maintain despite displacement. These workshops reaffirm that architecture is most meaningful when it is community driven, designed, and built - shaped by those who inhabit it.

Qawasma critiqued the individualistic nature of contemporary architecture, arguing that the discipline should serve communities. She encourages designers to “dismantle the individuality of our work” and embrace architecture as a collaborative, socially embedded practices rooted in the needs and aspirations of the people it serves.

“...architecture is rooted in the community.” - Rania Qawasma

I had the opportunity to meet with Rana Abughannam online, a Palestinian architect and scholar who has worked with grassroots organizations in Palestine to rehabilitate design projects. In our discussion, Abughannam shared insights into her work and offered valuable perspective on my research. A key theme of her work was Heritage as a Practice of Resistance including typical everyday practices. She explored the different modes of learning created by Palestinians for Palestinians, structuring them into four timelines:

1.

2.

The First Intifada (1987-1993) – During an uprising in response to living under Israeli occupation, when schools and universities were frequently shut down, educators and faculty brought learning to homes, ensuring continued education despite restrictions.

Education on Campuses and Camps – The development of informal learning environments, as explored by Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, where education was integrated into a refugee camp, “to connect the site of knowledge production on the campus with the site of social stigmatization”

3.

4.

Collaboratively Building Knowledge – knowledge through shared experiences and dialogue

Alternative Learning Methods - Exploring different approaches to education, including remote learning, selforganized teaching methods, and flexible models

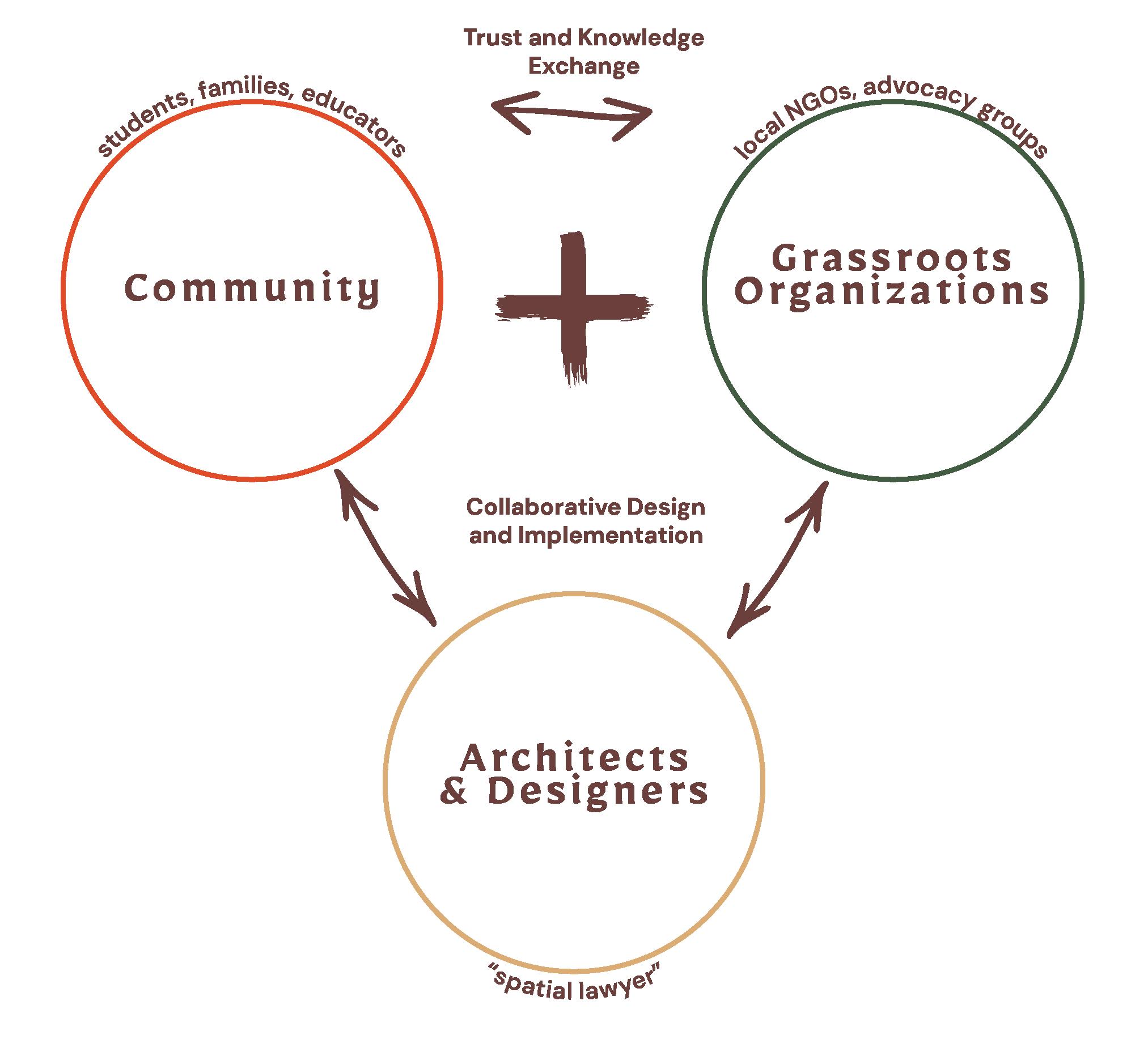

Through her experience collaborating with grassroots organizations in Palestine, Abughannam emphasized the importance of trust in building relationships with the community. Designers and architects must engage with communities out of genuine commitment rather than as “extractors of knowledge or data.” Palestinians continue to persist while living under siege, any design intervention must be rooted in sincerity, collaboration, and respect.

Abughannam also provided feedback on the “Timeline” that I presented, which was based on the Education Cluster’s response plan. I had identified a gap in the plan and proposed “Transitional Learning Spaces,” as a semi-permanent, long-term solution for sustaining education in Gaza while schools and critical infrastructure are rebuilt. While I noted that Palestinian-led initiatives are already in progress, there was no mention of designated educational spaces. However, she advised me to reconsider how education could be integrated into existing frameworks rather than introducing new structures. This raised a broader question: Could learning take place in spaces beyond traditional classrooms or newly designed structures?

”en(COUNTER)s in Palestine,” Rana Abughannam, University of

”en(COUNTER)s in Palestine,” Rana Abughannam, University of

Architects’ and designers’ role is to provide spaces for opportunities. As Rana Abughannam said, “What we design offers places to create community,” to balance urgency with long-term it takes patience and time – every action we take can be considered a step forward. A space created with the community for the community helps keep them functional (Working with grassroots organizations helps the spaces remain functional).

In an interview between Rana Abughannam and Sandi Hilal, Hilal emphasized the role of an architect goes beyond designing it reforms into being a Spatial Lawyer. To start by addressing the problem by using law on the ground, within the community. By being a spatial lawyer, you fight for the marginalized group within the community and try to implement their needs without creating conflict (Sandi Hilal and Rana Abu Ghannam, qtd. in Petti).

“The community loved participating since it allowed them to vent their frustrations. It opened the possibility to change; a possibility to not accept the de facto situation. In that sense, I think that architecture has this potential of dreaming and thinking of other realities and being able to bypass the impossible.”

-Sandi Hilal

Sandi Hilal described the challenges of the community housing projects DAAR worked on. Every reconstruction project - whether repair or new - must be approved by the Israeli government, making it difficult to pass projects. For this project, Hilal advocated for a threestory structure with a central courtyard instead of the typical seven, as resident only had access to electricity for three hours a day, making upper floors impractical. This is where taking on the role of a “spatial lawyer” became crucial, ensuring the project remained functional while still accommodating the necessary square footage.

Despite these efforts, the project was ultimately rejected due to unapproved building materials by Israel – though no explanation was given as to which materials were deemed unacceptable. While the project was never built, the process itself was meaningful. By engaging in the design, the community was able to imagine a better future, demonstrating the power of participation even in the face of systemic barriers.

This proposed framework initially limited education to schools or new structures. However, as Abughannam suggests, learning can take place through practices of care and community, not just within a traditional classroom. This approach involves identifying and adapting planned or existing spaces – whether part of new developments led by Palestinians or within the existing built environment - for educational use. If a transitional learning space is needed, it should be designed collaboratively with the community, with learning as its primary function while accommodating other essential services, such as health services or food centers, to support broader community needs.

The idea of learning being different from education allows it to occur in different settings as Palestinians have done before. It leads to another rabbit hole explored by Munir Fasheh, he holds a strong stance that “There is no learning that is not radical.” In an interview with Mayssoun Sukarieh, he shared a story of when he was a student living in Ramallah, Palestine. The story showcased the value of a learning experience – he explained how the principal of the school would

take the students down to the village on Saturdays and through their experience there Masheh learned from the people he mentioned how they would sit around and discuss the newspaper of the day rather than each reading it on their own.

This radical approach to learning was also evident during the First Intifada (1987-1993) when young Palestinians responded to the closure of schools and universities by forming neighborhood committees. These committees, organized independently in the West Bank and Gaza, became spaces for self-sustained learning—covering functions such as education, healthcare, or food security. These grassroots initiatives were direct action, “the medium of learning” itself. Education took shape through expression, reading, and conversation young people shared their experiences, read together, and formed small discussion groups to analyze.

In this context, learning is resistance. It thrives in unexpected spaces and through unconventional means, reinforcing the power of education beyond the confines of institutions.

“There is no learning that is not radical.”

References:

“About.” DAAR, 19 Mar. 2024, www.decolonizing.ps/site/about/.

Al Qudwa, Salem. “Aesthetic Value of Minimalist Architecture in Gaza.” DigitalCommons@RISD, digitalcommons.risd.edu/liberalarts_contempaesthetics/vol15/iss1/14/. Al Qudwa, Salem. “The Reconstruction of Everyday Architecture in Gaza.” ASMA, 17 Jan. 2025, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Lecture. “Experiments in Radical Pedagogy in Palestine.” YouTube, Fobzu (Friends of Birzeit University), 17 Dec. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=djbj-kts_04. Petti, Alessandro. “Destruction and Reconstruction.” DAAR, 27 Nov. 2023, www.decolonizing.ps/site/cycles-of-destruction-and-reconstruction/. Proctor, Rebecca Anne. “Palestinian-Designed, Self-Build Homes Seen as Key to Gaza’s Recovery | Arab News.” Arab News, 2021, www.arabnews.com/node/1874316/middle-east. Qawasma, Rania. “Architecture, Identity, and Palestine.” From Isolated to Organized, 23 Feb. 2025, ZOOM. Lecture. “Rana Abughannam, En(COUNTER)s in Palestine.” YouTube, Waterloo Architecture, 26 Mar. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWWRrGA1dtg&t=1535s. “The Troubled Everyday in/of Gaza: Restoring Agency and Creative Possibility.” YouTube, Harvard Divinity School, 13 Mar. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI1hm8dcJRk.