State of Women in Baptist Life • 2025

Commissioned by: Baptist Women in Ministry, Inc. Waco, Texas

and Written by:

State of Women in Baptist Life • 2025

Commissioned by: Baptist Women in Ministry, Inc. Waco, Texas

and Written by:

The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2025 marks the 20th anniversary of BWIM’s publication of statistics and analysis for women in ministry among Baptists in this form.

The 2005 inaugural report provided an extensive history of the journey for women in ministry among many different Baptist denominations along with current statistics. The stated purpose for the report was “to validate the ongoing needs of Baptist clergywomen, bring to light growth and losses, and illuminate nationwide trends.” 1

Twenty years later these needs continue to exist. Statistics and research are incisive metrics and powerful motivators for progress. BWIM's hope is that the 2025 report will provide clarity, insight, celebration, and elucidation for the path forward.

Part One of the report contains a summary of research conducted by Dr. Heather Deal, who currently serves as Assistant Professor of Social Work at Binghamton University and previously served as BWIM’s Director of Development. Through a qualitative study, her research reveals markers of congregations that are creating environments of empowerment for women, continued realities that still exist even in empowering environments, and directions for further study and assessment.

BWIM partnered with Dr. Deal to conduct this research in response to the conclusion made in The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2021 that for women in ministry among moderate Baptists: “there is clearly still a large gap between what is professed and what is practiced.” 2

Part Two of the report provides current statistics and analysis on women’s ordinations in Baptist churches, women serving in ministry among Baptists as senior pastors and co-pastors, women endorsed as chaplains by Baptist denominational bodies, and Baptist women’s enrollment in seminaries. BWIM employed a researcher, Kara Nelson, a graduate of Baylor University and a seminary student at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, to help collect these statistics.

Many reasons for celebration can be found in this report, as well as painful reminders of the disparity that women in ministry face among Baptists.

Baptist siblings: we are not there yet. But our gains demonstrate that more progress is possible! May this report inspire you toward your next best steps in our shared vision of women being able to thrive as they minister and lead within Baptist communities.

With solidarity and hope,

Meredith Stone Executive Director

In the 2021 State of Women in Baptist Life report, BWIM named a significant disconnect revealed by the data–there is a gap between perceived support of women in ministry and the lived realities of women who are serving in ministry among Baptists.

Many Baptist congregations have experienced transformation in their theology surrounding women in ministry and moved to expressions of affirmation. However, this affirmation has not always been accompanied by changes in congregational practice.

86% of the women in ministry among Baptists surveyed for the 2021 report disclosed that they experience obstacles to their ministry because of their gender, even though 87% of respondents claimed their congregation has expressed some level of affirmation for women in ministry. These disparate statistics demonstrate the disconnect between the affirmation of women in ministry professed by some Baptist congregations and congregational practices which continue to create obstacles for women in ministry.

The gap between perceived support and the lived realities of women in ministry is evidence that affirming women in ministry solely in principle is not enough. Affirmation must also be embedded into a congregation’s culture or environment, which is found in the daily rhythms, decisions, and structures of the congregation. Congregational culture is the cumulative result of decisions made over time, such as who preaches, who leads, whose voices are honored, what behaviors are tolerated, and what language is normalized. Congregational culture is where theology meets practice, and thus is where Baptist women in ministry are either empowered or undermined.

Therefore, Baptist congregations must create empowering environments for women. BWIM defines empowering environments for women as environments where every woman has the opportunity and freedom to use all of her gifts in service to the church.

While many congregations might assume they are doing enough by calling women to pastoral and ministerial roles or by expressing support from the pulpit, our research reveals that true empowerment emerges from the “ground-up,” as well as from the “top-down.” “Ground-up” transformation is when change is made so that every woman in a congregation experiences an empowering environment, which then affects decisions related

to congregational and pastoral leadership. "Top-down" progress is when churches call women to leadership roles and express support from the pulpit. "Ground-up" transformation must accompany "top-down" progress in order for the experiences of women in ministry and women in the church to match professions of affirmation."

In order to effect change so that women in ministry can more often thrive without gendered obstacles, BWIM began considering how we can help Baptist congregations move from affirmation to action. Instead of asking the question, “How do we help women in ministry cope in unsupportive Baptist congregations?,” we moved toward questions of appreciative inquiry, such as, “What are the markers of Baptist congregations where women in ministry thrive?”

In response to this question, BWIM partnered with a researcher, Dr. Heather Deal, who was employed by BWIM as Director of Development at the time, to conduct research that would identify the markers of congregations which had created empowering environments for women.

The qualitative research included interviews with 15 female ministers serving in Baptist congregations which both ministers and outside observers identified as places where women felt deeply empowered in their roles. The identified congregations are not perfect; however, each has engaged, and continues to engage, intentional actions which promote the thriving of women in ministry in their midst.

Analysis of the interviews revealed consistent patterns across geography and size of the congregation. While the churches had many differences, the research demonstrated that the churches shared several commonalities which served as markers of the empowering environments they had created for women.

Therefore, Part One of The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2025 provides a researchbased profile of what Baptist congregational environments look like when they move beyond expressions of affirmation and to empowering actions. Through the six core commitments and practices included in this profile and explained below, we outline the shared practices, values, and postures that help congregations close the gap between belief and action. Direct quotes from the female ministers who were interviewed for this study are also included to illustrate the realities connected to these six markers.

Many congregations in the study described a gradual, decades-long journey toward fully affirming women in pastoral, ministerial, and congregational leadership roles. Progress often began with allowing women to serve as deacons, then moved to calling women as associate pastors or staff ministers, and eventually, sometimes after many years, calling women to serve in the senior pastor role.

In several cases, the first woman to hold a senior pastor position had previously served the church in another leadership role, such as associate pastor, which helped the congregation become comfortable with her leadership. The presence of female pastoral interns and emerging ministers also contributed to changing congregational culture, as these young women brought fresh perspectives and demonstrated the gifts and capabilities of women in ministry, further opening the door for future female pastoral leaders.

Affirmation of women extended beyond the pulpit to lay leadership roles, with many congregations emphasizing the importance of women in decision-making and committee leadership. While having women in visible positions of influence was important, the study found that intentionality was key—congregations paid attention to gender balance, age diversity, and broader inclusivity when filling leadership roles.

Women’s long-standing contributions to the life of the church were acknowledged, though participants noted that sustainable empowerment requires more than relying on women’s willingness to serve in multiple capacities.

True congregational empowerment values women’s leadership as essential, supports it equitably, and ensures representation in ways that foster a culture of shared responsibility and inclusion.

“I was the first woman called as pastor here in 2019 for a congregation that has been supportive of women in ministry since its creation in 1953…That's [more than] 60 years before they had their first woman pastor...They have had female associate pastors. They have had female interim pastors, but they never had a [senior] pastor.”

Congregations in the study fostered empowering environments for women through deliberate attention to gender equity in all aspects of church life. This often included using gender-inclusive language for God, incorporating intentional choices in worship and liturgy, and rejecting gender-specific structures and practices.

Some churches used expansive or gender-neutral pronouns for God and emphasized God’s transcendence beyond gender, reflecting a theological commitment to inclusivity. Intentionality extended to selecting gender-inclusive translations of the Bible, centering marginalized voices in worship, and incorporating resources like Dr. Wil Gafney’s A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church. Many also moved away from gender-segregated ministries in favor of inclusive alternatives, a shift that sometimes placed them at odds with denominational expectations but reinforced their commitment to welcoming all.

• Loving God

• Creator

• Redeemer

• Savior

• Sustainer

• God of Justice

• Gracious Parent

• Ever Present Lord

• Eternal Holy One

These practices were part of a broader, long-term cultural shift toward equity, often rooted in decisions made decades earlier, such as adopting gender-inclusive hymnals or consistently preaching about the image of God in all people. Leaders acknowledged that this work is ongoing and requires sustained commitment, self-awareness, and the willingness to correct mistakes when lapses occur. Even in the most intentional congregations, slip-ups in

“We try not to use male language to talk about God around here as much as possible so that people have a more open and free view of who God is as mother and father. This language is used in the pulpit and people will also say it in prayers."

Rev. Jillian Twiggs

inclusive language or practice were treated as opportunities for learning and growth. Persistence, rather than perfection, marked these communities as places actively working to create and sustain empowering environments for women in ministry.

“We don't have any gendered groups. It doesn't fit. The language just doesn't work here. I’ve even sometimes thought we should have a women's retreat. And then I think how that leaves out too many people. So we end up having a spirituality retreat, and anybody can go. Gender groups has just never felt right coming out of my mouth around here."

Nearly all congregations in the study had moved toward more feminist organizational structures, though each expressed this shift in different ways. Common actions included resisting hierarchical leadership models, embracing collaboration, facilitating consensusbased decision-making, and intentionally modeling feminine power.

Many leaders rejected the “pastor as CEO” model, instead creating flattened structures that emphasized trust, shared accountability, and mutual support. In some cases, this shift was reflected in small but symbolic changes, like listing staff names alphabetically rather than by rank, or eliminating formal personnel oversight in favor of collegial trust.

“I don't like the image of pastor as CEO. I don't love hierarchical models of ministry where you have one person who is the authority. I'm most inspired by churches that have a flattened structure, where my job [as the pastor] is…to hold it all together, to make sure each part is functioning and healthy. But my job is not to say this is how it's going to be."

Several congregations adopted co-pastor models, formally or informally, to share responsibilities and provide mutual coverage of pastoral duties. However, these changes required careful balance. Actions such as dismantling committees and not clearly delineating the boundaries for shared responsibilities had the unintended consequences of increasing burdens on staff.

Consensus building was a growing priority, with most congregations adopting aspects of models to replace or supplement majority-vote systems like Robert’s Rules of Order. While time-intensive, consensus approaches allowed more voices to be heard and fostered ownership of decisions.

Modeling feminine power was another important shift, with leaders embracing relational, transparent, and collaborative practices that challenged patriarchal norms. Some pastors described the tension between adapting to male-dominated structures and fully inhabiting their own relational and nurturing leadership styles. Co-pastors modeled healthy disagreement and mutual decision-making publicly, showing congregations how collaborative leadership functions in real time. Many also emphasized setting boundaries and refusing to engage with anonymous criticism, reinforcing a culture of accountability and respect.

When engaged together, these approaches toward non-hierarchical organizational structures created more equitable, trust-filled environments which empowered both leaders and congregants.

“I think we've learned that when there's something potentially contentious or just a big change, that we don't put it out there to the congregation or a vote immediately. What we do is educate the congregation, have a lunch and learn, a listening session--something to let people understand…so that people can have time to think about it, process it, and understand what's driving the need or the concern or issue. Because usually if you give people time to digest, think, and talk, then you can get around to knowing what the right thing to do is, or at least move people toward a time of decision.”

Congregations in the study created empowering environments for women by fostering intentional support networks at multiple levels—among peers, within church leadership, and across the congregation.

Peer support networks provided critical relational and professional connections that countered the isolation many women in ministry experience. These groups offered safe spaces to share resources, process challenges, and check in on one another’s well-being, sometimes sustaining connections for decades. Supportive church leadership also played a vital role by offering trusted guidance, protection, and advocacy. Leaders who intentionally checked in, helped navigate complex situations, and stood

publicly with women pastors, particularly in moments of controversy or scrutiny, reinforced an environment where women in ministry could thrive.

“It doesn't happen every week. It doesn't happen every month. But somebody in our peer group will reach out to say or ask something like: Have you done a [particular kind of] funeral lately? What is good language to use for a [certain] situation? If I kill my spouse, then will you all come see me in the penitentiary? My kid’s in therapy and I'm just so done with everything right this minute. And we get together, sometimes once a year, sometimes more than once, to be in the same place together for several days where the agenda is only checking in--sometimes hours at a time until we've caught up with each other and we know how to retain the connection that sustains us.”

Beyond leadership, congregational support proved essential for sustaining empowering environments. Members demonstrated this by offering visible encouragement during worship, meeting practical needs, and actively advocating for women’s leadership opportunities. Some ministers relied on a core group of supportive congregants to maintain presence and positivity during challenging seasons. In other cases, individual members championed women’s inclusion in worship and leadership long before their formal appointments. These acts of advocacy and presence helped create congregational cultures that not only welcomed women in leadership but actively reinforced their value, inclusion, and authority.

“I

trust [my personnel committee] completely…they check in with me regularly, and I have conversations with our current chair of Leadership Council and Vice Chair of Leadership Council all the time.”

Participants emphasized that addressing gender issues in multiple aspects of church life is essential for creating empowering environments for women. This includes preaching on gender equity, rooting women’s empowerment in congregational values, educating children, youth, and the wider congregation on gender and sexuality, and actively confronting sexism.

Pastors integrated gender equity into sermons both as a justice issue and by lifting up women’s perspectives in scripture, while congregations reinforced these values through purpose statements and storytelling that highlighted women in ministry.

"I would say at least using children's Bibles that have solid stories of women's roles as well as men's roles is vital. I think it is helpful for children to see both sides and relate it to their everyday life."

Education for children and youth often included promoting body positivity, challenging gendered dress codes, using inclusive language, and providing sexuality education. Education for the wider congregation ranged from structured programs to everyday teachable moments, ensuring members understood the importance of inclusive practices.

"I largely preach from a white western feminist perspective, but I also try to bring in womanist theologians, and a variety of voices. And I can remember so many women coming to me and saying, ‘I’ve never heard a sermon like that before.’”

Addressing sexism directly, whether from individuals or embedded in church culture, was seen as non-negotiable. Leaders named and challenged sexist language, double standards, and undermining behaviors, encouraging direct and constructive communication. They also

acknowledged the need to confront internalized sexism among women themselves, recognizing how ingrained biases could influence expectations, interactions, and leadership opportunities. By naming and addressing both external and internal forms of sexism, congregations worked to dismantle the barriers that undermine women’s sense of belonging and value. This comprehensive approach—preaching, teaching, reinforcing values, and actively confronting bias—was described as crucial for sustaining genuinely empowering environments.

Congregations in the study emphasized that egalitarian staff policies are central to creating empowering environments for women. These policies were designed to consider the whole person and their needs, with intentional practices in hiring, scheduling, leave, and safety.

Inclusive hiring approaches included broadening experience requirements, using genderblind resume reviews, and actively seeking women candidates for pastoral roles. Flexibility in work schedules, whether formal or informal, was common, allowing staff to balance ministry responsibilities with personal and family needs. Equitable leave policies reflected congregational values, offering non-gendered parental leave, foster leave, and sabbaticals aimed at rest and renewal rather than productivity. These measures ensured that women in ministry felt supported both professionally and personally.

Another critical element was the creation and enforcement of sexual misconduct policies, reflecting an awareness of the high rates of harassment and abuse in ministry settings. Training on sexual abuse prevention, annual policy reviews, and background checks for all volunteers working with minors or vulnerable adults were standard in some congregations.

“I want to do this job, but I need flexibility. And that was one of the things I remember we discussed [in my interview process]. Sundays and Tuesdays are requirements, but other than that, it's teleworking and flexibility in terms of what you can do at home. That was a huge part of me accepting the position.”

By combining equitable hiring, flexible work structures, comprehensive leave benefits, and robust misconduct prevention, these churches demonstrated a tangible commitment to equity, safety, and well-being for women in leadership. These policies created a structural foundation for sustaining empowerment within congregational life.

Despite significant progress in creating empowering environments for women, many congregations in the study still grapple with the lingering effects of patriarchy, most often expressed through gender-based microaggressions and benevolent sexism.

Participants described these behaviors as subtle yet pervasive, often going unnoticed by the congregation as a whole. Some pastors have formally raised concerns, sharing documented examples with church leadership to highlight how such comments and actions affect them personally and professionally. While these disclosures were often met with care and concern, participants expressed uncertainty about whether acknowledgment would lead to lasting change.

“Even in a congregation like this, that is wonderful and safe and great, there are still everyday moments of sexism in the way that we’re approached and treated. And if we made a list of them and read them to the congregation, they would be horrified, because they would say, 'That’s not us, we don’t do that.'

And it’s all the time.”

A common form of these gender-based microaggressions involved unsolicited remarks about women pastors’ appearance, often framed as compliments but carrying condescending or objectifying undertones. Such comments, whether about clothing, hairstyles, or physical attractiveness, were described as diminishing their professional role and authority, and in some cases felt invasive or inappropriate. Even in otherwise supportive congregations, these subtle behaviors reinforced gendered assumptions and revealed how women’s bodies and presentation are still a focal point for evaluation.

This persistence of microaggressions and benevolent sexism demonstrates that structural and theological reforms, while essential, are not sufficient on their own; dismantling patriarchal norms requires sustained cultural change that addresses both overt and subtle forms of bias.

"We do as women still get the condescending comments of: ‘You look cute today,’ ‘I like your skirt,’ ‘I like your outfit,’ ‘You’re so pretty.’ Kind of like we're their granddaughter."

For those who are aware that affirmation alone is not enough to create an empowering environment for women in their congregations and want to actively work towards transforming their congregational environment, the first step is understanding the attitudes and actions toward gender equity in the congregation.

BWIM is working with scholars who research the areas of congregations and gender equity to develop a tool which can help congregations in this assessment. The development and first pilot of this tool occurred in the Spring of 2025 with six congregations using the assessment. While this tool is still currently in development, it assesses a congregation’s attitudes and actions toward gender equity around several key factors: hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, theological sexism, and structural sexism.

Hostile sexism in the church refers to overtly negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that reinforce traditional gender roles and seek to limit women’s participation, influence, or authority within a religious setting.

Benevolent sexism in the church refers to attitudes and beliefs that, while seemingly positive or protective toward women, ultimately reinforce traditional gender roles and limit women’s autonomy and leadership within the religious setting. This form of sexism often idealizes women as morally superior, nurturing, or naturally suited to supportive roles, which can lead to restrictive expectations about their place in church life.

Theological sexism in the church refers to attitudes and beliefs grounded in religious teachings that may reinforce gender hierarchy, such as interpretations of scripture that prescribe specific roles for men and women or promote male authority.

Structural sexism in the church addresses the organizational practices and policies that create unequal access to leadership or influence based on gender. This includes the formal and informal rules that may limit women’s opportunities to participate in decision-making or assume high-status roles within the congregation.

In 2026, BWIM will continue our partnership with scholars and researchers to conduct a second study to refine this assessment further, capturing congregational attitudes and actions as well as providing feedback to help congregations as they seek to actively work to create empowering environments for women in Baptist congregations.

Counting and celebration are in BWIM’s DNA.

One of BWIM’s foremothers, Dr. Sarah Frances Anders, began the practice of tracking the ordinations of women in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) in the late 1970s.

In June 1982 she presented a paper at a dinner for women in ministry as a part of the Women’s Missionary Auxiliary (WMU) Annual Meeting. At the time she estimated 140 women had been ordained in SBC affiliated churches, and 6 women were serving as senior pastors of SBC affiliated churches.

Her presentation, along with several other key events in 1982, were catalytic in starting the organization that is now known as Baptist Women in Ministry.

Continuing the practice of keeping data and statistics on women in ministry among Baptists became integral for BWIM to track growing and declining trends, but it also became a means of celebration.

In June 1983, the first issue of Folio, a quarterly newsletter for Southern Baptist Women in Ministry, was published. One of the regular aspects included in Folio was an “Ovations” column in which the ordinations and new calls of women in ministry were announced and celebrated. As BWIM grew over the years, the practice of celebrating the successes of women in ministry continued in Folio and its successor publication, Vocare, and most recently on social media.

Twenty years after the first report, and over forty years after Dr. Anders presented her paper, BWIM has expanded to be inclusive of all Baptist denominational groups beyond only the SBC, and continues to value keeping statistics as an act of celebration—which is the first of BWIM's current organizational values.

Like positivity, celebration which is unbalanced can become toxic. BWIM must and will continue to name and challenge the injustices that women experience among Baptists.

However, one of the ways we resist gendered oppression is to celebrate each time patriarchy’s hold on Baptists is defeated. When we celebrate the successes of women in ministry, we grab the bullhorn to shout in patriarchy’s direction that we know it can be beaten.

As women existing in patriarchal systems, we are often taught, whether consciously or unconsciously, to feel ambiguously or suspicious about the successes of other women.

Female hostility is a real obstacle of internalized gender bias that women must combat in themselves. Unconsciously, women may have gut reactions toward other women's successes by questioning her credentials, how she got the job, if she is sufficiently equipped, etc.--which oftentimes amounts to subconscious jealousy that another woman was successful in a way that a woman felt unique in achieving or was not successful herself.

This type of hostility exists in all oppressed groups as described in postcolonial theory's concept of horizontal violence.3 If oppressed people fight against their oppressors (vertically), they know they will likely be crushed. So instead, their hostility comes out sideways (horizontally) against others who are oppressed in the same way they are and who are all vying for what they perceive to be a small, limited quantity of opportunity.

So by celebrating the successes of women in ministry, women (and men) can boldly defy internalized sexism and the way patriarchy gaslights women into believing only a limited quantity of empowerment exists.

Therefore, with a spirit of celebration and bold defiance, we present to you part two of The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2025.

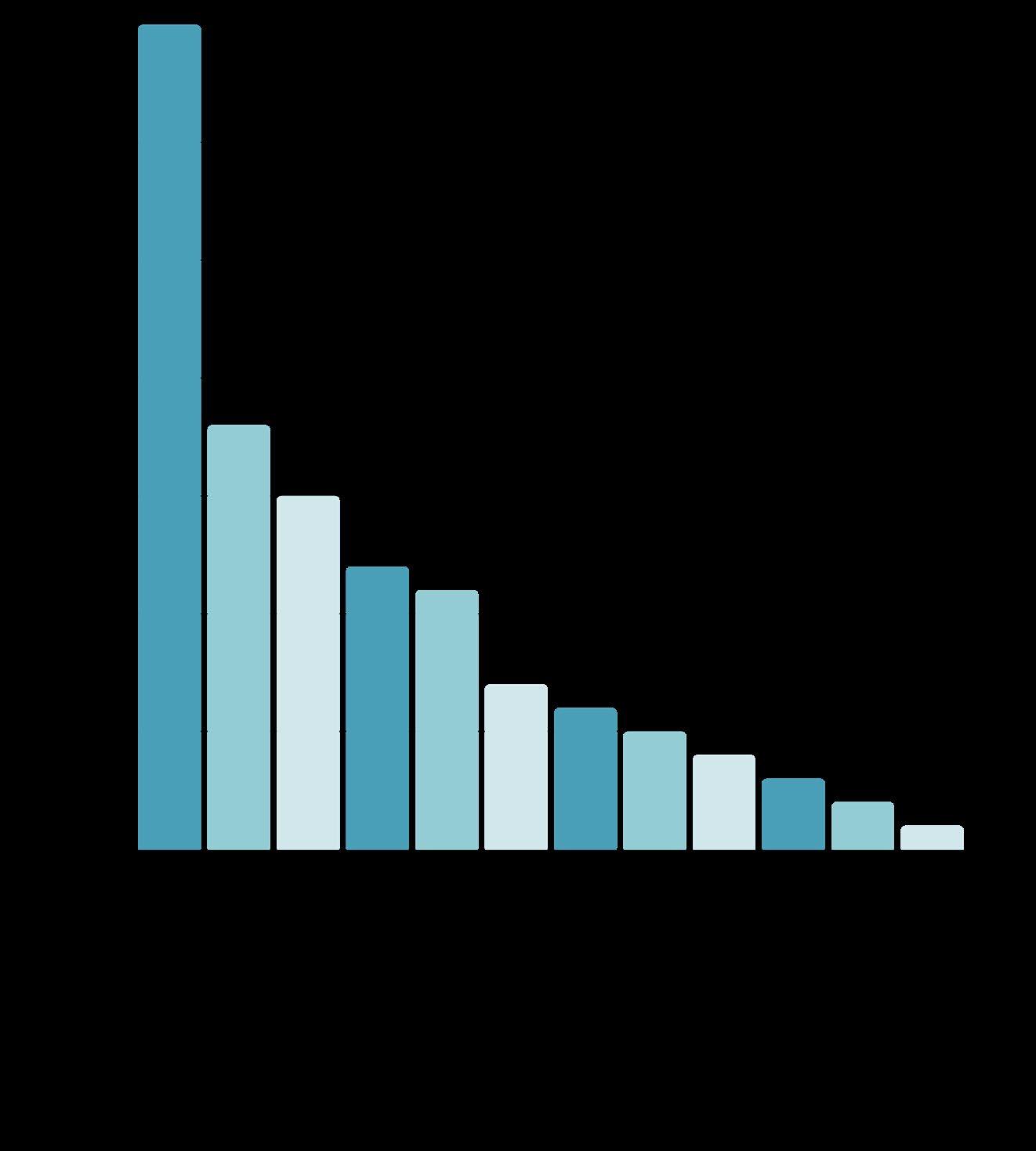

At the time of the 2021 report, BWIM’s records estimated 2,722 ordinations of Baptist women since the ordination of Addie Davis, the first Southern Baptist woman ordained to ministry in 1964. For the past 20 years, ordinations were largely gathered from women’s self-reporting to BWIM, various Baptist media outlets, newsletters, and social media.

Because the record-keeping is informal, this number cannot account for all ordinations. The true total of ordinations in this time period is likely much higher—not to mention the countless women who were not ordained but have served in various ministerial capacities. However, BWIM’s informal record-keeping signposts the overall trends of women’s ordination in the Baptist world.

2,856 ordinations of Baptist women since 1964 as estimated by BWIM's records

For this report, BWIM recorded the ordinations of 134 women from the beginning of 2022 to the end of 2024. Adding to the total from the 2021 report, BWIM has counted 2,856 Baptist women ordained to the gospel ministry.

With each ordination recorded, we celebrate that a Baptist congregation has formally identified and honored a woman’s gifts for and calling to ministry, especially when so many women have been denied that recognition for millennia.

The yearly average of 45 was slightly less than the yearly averages noted in previous reports, but did not show significant fluctuation. However, the slight decrease will be watched closely to determine if it is a trend.

Texas (18), Georgia (15), Virginia (12) and South Carolina (11) each had high totals for the threeyear period, but North Carolina’s total (35) significantly exceeded each of those states. Previous reports have noted the presence of higher numbers of ordinations near moderate-to-progressive Baptist seminaries, and with multiple such seminaries in the state of North Carolina, it could account for a higher number. Additionally, BWIM has consistently had a staff member living in the state of North Carolina, and BWIM North Carolina is the most robust of the state/ regional BWIM groups. Thus, with greater BWIM presence, it is possible that more ordinations were observed and reported.

"When I first began the conversation about ordination as a seminary student, I never could have imagined the depth of love and support my home church would show in the face of opposition from the SBC. They courageously affirmed God’s call on my life, and I will always carry that gift of love with deep gratitude."

-Rev. Jordann McMahan Pastoral Resident, Wilshire

While the majority of the ordinations BWIM records are in congregations affiliated with denominational groups that are open (to varying degrees) to women serving in ministerial and pastoral roles, some of those congregations have multiple affiliations which may include denominational groups that are more limiting to women, such as the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) which is the largest Baptist denominational group and second largest Protestant denomination in the United States.

In 2023 and 2024, the SBC took public action to disfellowship one of their largest churches, Saddleback Church, over Saddleback’s ordination and appointment of women to pastoral roles, and made efforts to pass a constitutional amendment banning churches from affirming, appointing, or employing women to any pastoral role.

While the constitutional amendment did not pass the necessary two successive votes, Saddleback Church, along with other churches disfellowshipped in those years, were used as examples to threaten SBC affiliated churches which might still be affirming of women in ministry to some extent.

When significant public actions like these take place, churches might be inclined to stifle potential ordinations of women to not appear in contradiction to the trajectory of the SBC. However, BWIM also observed that some churches responded by acting boldly in their support of women in ministry in order to make their affirmation clear. In either case, BWIM will monitor the trends of ordinations over the next few years to determine if actions of the SBC have an effect. BWIM desires that every Baptist woman have the opportunity to fully utilize her unique gifts and calling for any role to which God may lead her. We recognize and honor the many ways women serve in every type of ministry in the church and outside of the church.

Rev. Madison Harner Watts, ordained March 6, 2023 at Weatherly Heights Baptist Church, Huntsville, AL

BWIM has traditionally tracked the number of women serving as senior pastors and co-pastors of Baptist churches not because we believe those roles are more important than others, but because (1) in the nonbureaucratic Baptist world, it is a more accessible statistic to track; and (2) progress in senior leadership positions tends to reflect progress in other positions as well.

While these statistics are an important hallmark for the progress of women in ministry among Baptists, we also celebrate the great gains and opportunities women are experiencing in other areas of congregational ministry such as associate pastors and pastors/ministers for children, youth, college, adults, music, worship, missions, education, formation, social work, women’s ministry, and more.

North Carolina continues to be the leading state for women serving as senior pastors or co-pastors of Baptist congregations, with Texas and Virginia coming in second and third, respectively.

*The state-by-state statistics only include the women serving in senior pastor and co-pastor roles of whom BWIM has record by name, church, and location. Since ABCUSA only provides numbers and not individual details or a state-by-state breakdown, their statistics would significantly increase the numbers in states where there is a strong ABCUSA presence.

Between 2021 and 2025, five of the denominational groups BWIM tracks experienced growth in both the total number of female senior pastors/co-pastors and in their total percentage of women serving in senior pastoral ministry.

Four of those are Texas Baptists (BGCT), General Baptist State Convention of North Carolina (GBSC-NC), Baptist General Association of Virginia (BGAV), and District of Columbia Baptist Convention (DCBC).

The largest growth was in the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (CBF) which grew from 105 female pastors at 7.4% to 142 female pastors at 10.0%. The number of pastors represents a 35% increase from 2021 to 2025 which is highly encouraging for CBF’s trajectory of progress for women in ministry.

The Alliance of Baptists experienced a small decrease from 60 female pastors at 45.1% to 51 female pastors at 40.5%. Despite the reduction, the Alliance of Baptists remains the standard-bearer and leading Baptist denominational group for women’s opportunities in ministry.

Rev. Carrie Veal, Pastor of Second Baptist Church Lubbock, Texas

American Baptist Churches USA (ABCUSA) also experienced a decrease. In 2021, American Baptists reported 440 female pastors out of 3,249 total pastors. In 2025, the total number of female pastors has decreased to 360 out of 3,349 total pastors. Rather than the total number of affiliating churches, these numbers include the total number of senior pastors whose ordination is recognized and reported by ABCUSA Regions.

"The findings of the 2025 State of Women in Baptist Life are both a profound encouragement for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and also an unavoidable call to more growth and transformation. The fact that 10% of our congregations are now served by women senior pastors or co-pastors is a measurable step forward from the last study, not only in percentage but in actual number of congregations being led by women. At the same time, we still have far to go to reach the point where there are equal numbers of congregations led by women and men in CBF. Because we believe deeply that women and men are equally called to all forms of leadership in the church, and that congregations only fully flourish in faithfulness when the gifts of women can be unleashed as freely and powerfully as the gifts of men, we obviously still have work to do in our Fellowship and in our congregations."

-Rev. Dr. Paul Baxley, Executive Coordinator, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship

PNBC is proud of our history. We are proud of our inclusion. We don’t just talk about it- we walk it out. We are proud of our 2nd vice president, Rev. Dr. Jaqueline Thompson who is in line to be the next president of our denomination. We believe women are equal to their counterparts. We are unapologetic in that support. We are not in competition with other denominations, we just follow what we believe the Bible says. On the main stage [of the convention], you will find inclusion. You will find inclusion in the preaching and teaching. It’s been a part of our beginnings, but it has taken another level under the leadership of Charles Adams. We are a social justice organization and we take equality seriously.

-Rev. Dr. David Peoples President, Progressive National Baptist Convention

The Progressive National Baptist Convention (PNBC) was founded in 1961 during the Civil Rights Movement “to transform the traditional African American Baptist Convention, as well as society.”4 While we are unable to provide statistics on female senior pastors and co-pastors for this report, PNBC includes congregations where Black Baptist women in ministry are finding opportunities to serve.

Overall, with five denominational groups demonstrating growth, the trends for women’s opportunities as senior pastors or co-pastors in Baptist congregations are evidence that God’s call on the lives of women is being named, recognized, affirmed, nurtured, and being given opportunity for expression among Baptists more than ever before.

Women frequently minister in the fields of chaplaincy and counseling, serving in medical and hospice centers, correctional facilities, colleges and universities, all branches of the United States Armed Forces, and other specialized settings.

to right) Chaplains

Nikki

“Chaplaincy has been the vocational home where my gifts and calling have found their fullest expression. I am deeply grateful for the support of my Baptist faith community — through ordination and ecclesiastical endorsement — which makes it possible to serve in this sacred work.”

-Rev. Alice Tremaine, MDIV, MSL, BCC, Advance Care Planning Manager, Baptist Health, KY and IN

For the four endorsing denominational groups tracked in both the 2021 and 2025 report (Alliance of Baptists, Baptist Chaplaincy Relations, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, and General Baptist State Convention of North Carolina) the percentage of active endorsed chaplains and counselors remained relatively consistent.

American Baptist Churches USA’s endorsing agency also provided statistics for the 2025 report with a note that while 210 women are actively serving, other women are endorsed who may also be active but have not updated their records.

“American Baptist women serving as chaplains in the military, healthcare facilities, correctional institutions, hospice care, veteran administration, airports, campus ministry, and other specialized settings, embody courageous and compassionate leadership in some of the most critical and complex spaces of our society. Their faithful presence not only meets deep spiritual needs—it also reflects the growing impact and promise of women’s professional ministry across Baptist life.”

-Rev. Dr. Patricia Murphy, BCCI, Ecclesiastical Endorser & Director of Spiritual Caregivers

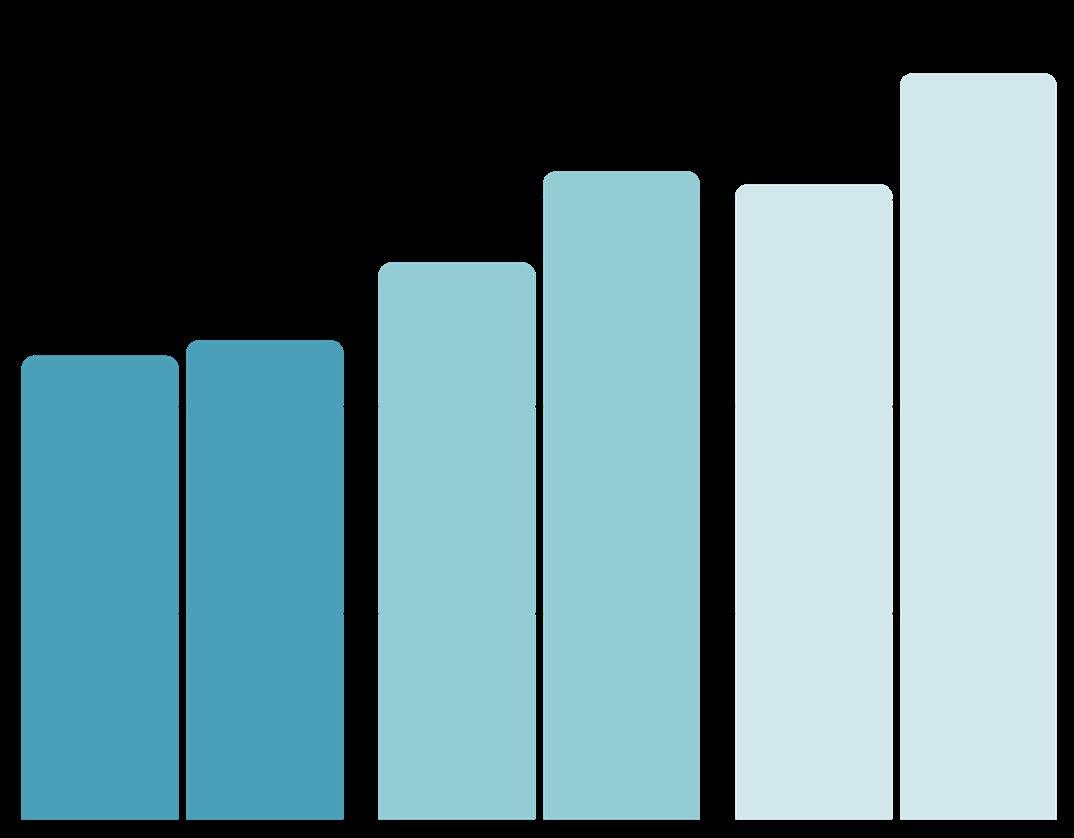

Examining the enrollment rates of female students in theological schools offers perspective into the future of women in ministry. The numbers in the charts represent enrollment for Fall 2024 in comparison with enrollment numbers for Fall 2021 as featured in the previous report.

For the institutions with a Baptist affiliation, the numbers include all enrolled students in master’s- level and Doctor of Ministry programs. For the schools without a Baptist affiliation, the numbers below represent enrolled students who self-identify as Baptists or who are connected with a program for Baptists at the seminary.

Three of the Baptist schools included in the last two reports had a higher percentage of female students enrolled at the Master’s level in Fall 2024 than in Fall 2021: Baylor University’s Truett Seminary (44.9% to 46.4%), Central Seminary (53.9% to 62.7%), and a notably significant increase at Campbell University Divinity School (61.5% to 72.2%).

Overall, the total percentage of Baptist female students enrolled at the Master’s level increased from 51.6% in the schools reporting their Fall 2021 enrollment to 52.4% for the schools reporting Fall 2024 enrollment.

The continued increase is also notable in that the total percentage of Baptist female students enrolled in Master’s level seminary programs in Fall 2024 (52.4%) is higher than the total number of female students entering Master’s level seminary programs in all theological schools affiliated with the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) in Fall 2024 (47.4%).5 These statistics demonstrate that women are responding to God’s call at higher rates among moderate-to-progressive Baptists than the average of other denominations in North America.

“The enrollment of women has increased at Campbell University Divinity School (CUDS) because we seek to create a space where women are affirmed and supported. Affirmation includes courses focused on women's experiences, classrooms where women's voices are valued, women faculty, women in leadership, women chapel preachers, special lectures featuring women scholars, and course texts written by women. Support includes providing options for course modalities to fit diverse schedules, generous financial aid, partnering with organizations that also support women, highlighting the experiences of women students, and staff, faculty, and fellow students showing up for women outside of the classroom when they preach, teach, and are ordained.

-Rev. Dr. Sarah Boberg, Assistant Professor of Christian Education, Campbell University Divinity School

For Doctor of Ministry programs, the percentage of female students enrolled increased at all of the schools that reported enrollment for both the Fall 2021 and Fall 2024 semesters.

Moreover, the total percentage of Baptist female students enrolled in Doctor of Ministry programs increased from 26.2% in schools reporting Fall 2021 enrollment to 36.7% for schools reporting Fall 2024 enrollment. This percentage is higher than the total number of female students entering Doctor of Ministry programs in all theological schools affiliated with ATS in Fall 2024 (31.9%).6

Such a significant increase over only three years demonstrates concerted and intentional efforts by the Baptist programs to reach female students, make programs more accessible to the needs of female students, and provide better financial assistance to female students seeking Doctor of Ministry programs that may not have been as accessible in the past

BWIM is highly encouraged by the steady progress for women in ministry among Baptists which is represented in this report. Not only do we celebrate the areas in which statistics show increases, growth, and opportunities, we also celebrate the churches and women who helped name the aspects of congregational environments where women thrive.

However, there is still much work to be done. While most of the denominations included in the report show growth in the percentage of women serving as senior pastors or co-pastors, none meet the goal that 50% of all Baptist pastors would be women. Moreover, though more than 50% of Master’s level Baptist seminary students are women, still only 36.7% of Baptist students in Doctor of Ministry programs are women.

While the statistics following ordinations, pastors, chaplains, and seminary students represent “top-down” progress, Part One of this report demonstrates the essential task of pairing that progress with “ground-up” transformation. As more churches engage the work of cultural shifts toward empowering environments for women, the stained-glass ceiling will continue to crack.

This report has attempted to capture the current conditions for women in ministry among Baptists in 2025, but the portrayal would be incomplete without acknowledging the broader cultural shifts in the United States which are threatening women’s rights and opportunities to thrive. Without doubt, the direction of U.S. culture, society, and politics will shape churches, whether in accommodation or resistance, and thus shape the lives of women.

Women have, and will always be, crucial to the church’s ability to further God’s grace and redemption in the world. With the progress that this report portrays, we hope you will be able to catch a glimpse of a world in which there are no limits or barriers to how women can participate in furthering God’s work, and therefore also no limits to how God might work among us.

1 Eileen R. Campbell-Reed and Pamela R. Durso, The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2005 (Atlanta, GA: BWIM, 2006).

2 Laura Ellis and Meredith Stone, The State of Women in Baptist Life Report 2021 (Waco, TX: BWIM, 2022).

3 For the origins of understanding horizontal violence, see Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (current edition with English translation: Grove Atlantic, 2007).

4 Progressive National Baptist Convention, History of PNBC, https://pnbc.org/content/historyof-the-pnbc/; Accessed 20 August 2025.

5 Association of Theological Schools, Total School Profile Reports, https://www.ats.edu/TotalSchool-Profile-Reports, accessed 6 August 2025.

6 Ibid. THE STATE OF WOMEN IN BAPTIST LIFE REPORT 2025 was researched and written by:

Assistant Professor of Social Work

Binghamton University

Binghamton, New York

Director

Georgia

BWIM's staff has created a consultation for church staffs and lay leadership which serves as an assessment of the six markers of congregations that are empowering for women. If you would like to schedule an in-person or virtual consultation, please reach out to us.

To read about more of BWIM's programs and initiatives that support and advocate for women in ministry, go to www.bwim.info.

BWIM STAFF

Rev. Dr. Meredith Stone Executive Director meredithstone@bwim.info

Rev. Nikki Hardeman Director of Advocating for Women in Ministry nikkihardeman@bwim.info

Rev. Barbara Lavarin Director of Supporting Women in Ministry barbaralavarin@bwim.info

Lauren Trowbridge Director of Development laurentrowbridge@bwim.info

P.O. Box 7458

Waco, TX 76714