Bayer is honoured to support Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture.

We believe in recognizing and promoting women's contributions across every facet of Canadian agriculture to help shape a more vital, creative and inclusive future we're all proud to be a part of. We're committed to pushing our industry forward by embracing women's unique perspectives, their invaluable contributions to the industry, and continuing to farm for change.

Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture (IWCA) is a recognition program designed to honour, highlight, and celebrate the work women are doing across Canada’s agriculture industry.

Now in its fourth year, IWCA is proud to present the six women chosen as the 2023 Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture.

Please join us in congratulating: Ana Badea, research scientist, barley breeding and genetics, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC); Della Karen Campbell, farm manager, Everdale; Kelly Daynard, executive director, Farm and Food Care Ontario; Judith Nyiraneza, research scientist, AAFC; Darby McGrath, VP, research and development, Vineland Research and Innovation Centre; and Heather Wilson, research scientist, adjunct professor, University of Saskatchewan.

These leaders have already shared their stories, wisdom, and insights in the IWCA podcast series on AgAnnex Talks, a podcast channel presented by Top Crop Manager , Potatoes in Canada , Canadian Poultry , Fruit & Vegetable , Drainage Contractor and Manure Manager magazines. Now, we’ve included highlights from those inspiring conversations in this digital publication.

And for the first time, the IWCA program will culminate with an in-person event November 7 th in Hamilton, Ont. This occasion will bring together women from across the industry to share in their experiences, offer guidance and advice in an interactive setting. Visit agwomen.ca for more information and to register.

The team behind IWCA wishes to extend a sincere thank you to our audiences for participating in the program, and to our sponsors for their support.

Enjoy these leaders’ inspiring stories in the pages ahead!

14 12 6 4 8

Ana Badea AAFC

Karen Della Campbell Everdale

Kelly Daynard Farm and Food Care Ontario

10

Judith Nyiraneza AAFC

Darby McGrath Vineland

Heather Wilson University of Saskatchewan

Join us November 7, 2023 in Hamilton, Ont., for our fourth annual IWCA Summit and first in-person program. This event is designed to inspire and educate women in agriculture..

Q&A with Ana Badea

To hear our full interview with Ana, visit agwomen.ca

AAFC’s Ana Badea contributes significantly to the Canadian agriculture and barley industry on many levels.

By Derek Clouthier

Ana Badea is a Manitoba-based research scientist for barley breeding and genetics, leading Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) largest two-row and hulless barley breeding program at the Brandon Research and Development Centre.

Badea is also involved in the development and training of the next generation of researchers and agriculture professionals as an adjunct professor at the University of Manitoba, where she helps guide graduate students as a co-supervisor and member of the advisory committee.

In this interview, Badea and agriculture editor Derek Clouthier talk about her research, what drives her passion for agriculture and where she hopes to see the industry go in the future.

What do you like best about being a research scientist for barley breeding and genetics?

I am involved with training graduate students as a course supervisor or a member of the committee. Anytime I have an opportunity and I’m invited by universities, either nationally or internationally, to talk about breeding in general or barley breeding or genetics, I take up these opportunities. As well, any opportunities to be a judge at a science fair or at conferences and symposiums for the student presentations. I love being involved in training the students.

I think it’s very important, and education is key. I’m not talking about only education in one aspect; I’m talking about education in general. Everything that is related to work and work ethic and the skills that are required. I hope that we are able to instill in them the patience and passion for conducting research and taking the time to see things grow. Agriculture is something that takes time.

As a scientist and a mentor, there is nothing better than seeing the students succeed and seeing them achieve their goals and be the best version of themselves. I cannot be happier that I am able to be part of their journey. It’s a big responsibility, but it’s also very fulfilling.

How did you end up in the field of agriculture and now as a research scientist?

It all started when I was very young. I needed to be connected to the land; I needed to be in nature. I used to love running with bare feet in the grass in the morning as a child. I was mesmerized by the dew on the leaves and being there in nature. When I had to choose what to do, there was no question. Enrolling in the university’s agriculture and science, that was it for me.

I was fortunate to be invited to join the Breeding and Genetics Club at the University of Manitoba, which was the opening for me for everything in science, genetics, and breeding. There I conducted my first scientific experiments, participated in many scientific debates, and was able to present the results of my re -

“I needed to be connected to the land; I needed to be in nature.”

search at various symposiums or conferences organized for students – the real conferences – which was amazing. This is why I think it’s really important to start as early as possible, and this is why I’m so happy to start with high school students – we do not wait until university.

As a breeder, there is nothing more rewarding than seeing partners adopting new levels of cultivars and seeing how they bring benefits to the farm and the value chain as a whole. It is a feeling I cannot describe. Being in Alberta, I remember being immersed in a field of barley…it was like an ocean. You look around and all you see is that golden barley that is undulating in the wind. When you go harvesting and you see those plump barley grains coming in the grain truck, it is exhilarating.

I was fortunate enough for the past few years to be part of an on-farm project, and our farmers across Manitoba had the opportunity for the first time to grow some of our new barley varieties

as well as other breeding programs. I was able to participate in harvesting, and it was amazing. These are moments for a breeder that make all the work worthwhile.

What is the biggest risk you have taken, either in your life or in your professional career?

Working in agriculture, as well as a research scientist working in breeding, risk is part of our professional lives. We take risks all the time; however, it’s a calculated risk. We always look at what the damage is and what we get in exchange. We balance it very well, and we always have several plans. Working against the elements isn’t easy, as you know; they can be your best friend and the very next minute, your worst enemy.

I’m speaking here about heat, drought, excess moisture…they can all take place with not much warning and sometimes in the same year. As we’ve seen in the past few years, very wet springs and very dry summers. So, there’s not a lot we can do to protect our material once it’s in the field.

Losing breeding material because of this can have a negative impact and set back the program. So, for us, each year when we have to put the limited amount of seed that we have in the ground, it is a risk, and we have to do that each year. It adds pressure, but it also adds great satisfaction.

What is a particular challenge you have faced recently and what did you learn from that challenge?

Dealing with the climate is one of the hardest challenges, and that’s for any farmer. One of the biggest challenges was not one but two rounds of flooding of the Assiniboine River in the same year.

We received warnings about the first wave of flooding, and right away we made different plans, found different locations, and shifted quickly.

I’m talking about thousands of plots that needed to be relocated, so we did that, and we had our grain safely in the ground, and we were happy. A few weeks later, a second wave came. It was the hardest thing to see.

Anyway, I am a positive person, and I like to see the highlights…it is a learning lesson, so I feel strongly that it was the best team-building exercise that our team underwent. It brought us closer; it pushed us to think, to see, to find different ways to protect the program. Also, it reminded me that breeding cannot be in a silo.

Can you pinpoint a defining moment that was a turning point in your career?

For me, it was when I was entrusted with the leadership of the western barley breeding program in 2017. This is AAFC’s flagship barley program. This was and still is a big responsibility for myself and our breeding team here. Western Canada is where the majority of barley is grown, about 95 percent. We have to protect the reputation that Canada has globally as being the fourth largest producer of barley and the second largest exporter of malt barley. That was a turning point in my career.

As a mentor, for me, when the first

graduate student applied for a job that we trained him for, and he got the job and he’s still in that position and doing great.

And as a breeder, when the first barley cultivar was registered, it was licensed, and was adopted by the growers and the end-users. Those would be highlights I look up to.

What advice would you give to someone looking to pursue a career in agriculture?

My grandfather said to me, ‘Always respect the land and the animals on your farm. They are the ones feeding you.’ These days, we talk even more about being respectful, and the fact that the land is not ours; it is something borrowed for the next generation, and we have to be mindful and look after it.

For the next generation, I would want to remind them that agriculture is so versatile and offers such a diverse and complex array of choices. Once they find that thing that uplifts their hearts and makes them happy, stick with that. •

Q&A with Karen Della Campbell

To hear our full interview with Karen, visit agwomen.ca

By Alex Barnard

Excitement can be an excellent motivator and guide in the right circumstances, as Karen Della Campbell’s experience shows. Deciding to start a market garden with her then-boyfriend, now-husband in 1995 has led to a plethora of social, educational and charitable initiatives, and a network of former interns that spans Ontario, the Prairies, and beyond. Campbell brings Everdale’s operational values of curiosity, trust and equity to every endeavour she takes on.

Her conversation with agriculture editor Alex Barnard covers how she first got into agriculture, how she views farms as a space for people to come together and connect with each other and the land.

Tell us about how you got involved in agriculture. I came to agriculture almost 30 years ago in a non-traditional way. Back in 1995, I was actually studying to be a midwife. That path had taken me to Edinburgh in Scotland, to Oregon, to New Mexico – it took me all over the place. But when we were in Eugene, Ore., there were a lot of farmers markets, local farms, people making cheese, people making spirits, local brewers, all sorts of things. My boyfriend, now husband, and I both fell in love with what was happening. I was really excited about that because I hadn’t seen anything like it here in southern Ontario before.

We had an opportunity to move to Marsville, Ont., and start a market garden. We started selling vegetables at the Guelph Market and it was an amazing year – the market garden was really successful. A lot of people would stop in to ask what’s going on, what’s a market garden. We were just learning as we went, literally with books in our hands every step of the way – so naïve it was ridiculous but loving every minute of it and making money off it. So, we continued with that.

A couple years later, that farm was going to change ownership, so we needed to find new land, and purchasing land wasn’t an option for us at the time. One day, a teacher from Everdale, which used to be a free school in the 60s, came to us and said, “I heard that you’re looking for a new farm. Why don’t you come and check out Everdale? We’re looking for farmers.”

So, we visited the farm and it is a beautiful, beautiful farm – it feels really special, really influential. It felt like home right away. However, while there had obviously been a lot of love and care at one point in time, at that moment there was a lot of disrepair. So, we thought let’s just start with what we know, continue to grow on that and see if we can adapt it to this space and start something.

Was there an example you wanted to bring to Ontario from your experiences in Oregon, or was it more the sense of community in agriculture?

I think we were just excited to grow food. At that point in time, we didn’t really have an understanding of the community that can happen on a farm, or the connection through food in that way. Through the farmers markets and a fairly large wholesale business, we formed these really strong relationships, because there weren’t a lot of people doing what we were doing in southern Ontario.

After about three years, we started to have more infrastructure in place and more capacity on the site. Once those were in place, we had more space to do other things and we passionately wanted to do an education piece. My background is also working with youth – I’ve worked with youth ever since I can remember, running different programs. We started to work with FoodShare and they started to send their youth to the farm.

Everyone talks about it as being the “Aha!” moment – we started seeing the youth that were coming up to the farm having those moments and seeing how that positive, emotional change was carried into their lives. So, we thought let’s dig deeper into this.

That was the genesis of our youth programming. Then, two or three years after that, we started an internship program, which is basically a skills- and knowledge-based program about the general principles of sustainable agriculture – from our perspective, but also from other experts’ perspectives.

Folks of all ages would come to the farm for a primarily six-month, three-season program, including a field trip every week or two. So, interns could have this broader perspective of agriculture, because my

interpretation is different than yours or the person sitting next to me, and you never know where somebody is going to get excited.

For someone who kind of came to agriculture in a non-traditional way, you’ve really spread that love of agriculture to a lot of people who might not otherwise have that opportunity.

I think farms are really important places. Farms have the capacity to bring people together in a way that other spaces can’t, because they’re active. They’re animated. There’s growth happening. There’s change happening. There’s loss happening. And if people have the space and time to be on a farm and witness that and grab a hold of what holds value to them, then all these amazing things can grow, like environmental stewardship, soil stewardship, love of birds. There’s so much to learn, to see and do.

One of the things that happens repetitively on the farm, is people will come to our community harvest days in the fall, where we harvest our large field crops for food banks. The reaction of someone who is in grade three, and the reaction of someone who is 30 is almost identical when they’re pulling a carrot or beet out of the ground.

It’s just joy, contentment, excitement – this feeling of accomplishment. If you can build on that, and if folks are able to build on that in

Egg Farmers of Canada is proud to support the next generation of agricultural leaders through our young farmer program and women in the egg industry program

Contact your egg board to learn more.

their own personal lives and carry that forward, then I firmly believe that’s how environmental and social change can happen within the community.

Oh, there’s so many things I love about it. I love the people that I work with every day. I really value a team that is diverse in thought and backgrounds, because – this might sound strange but I kind of like it when things don’t go well. There are so many plot twists in farming and when those happen is when things are figured out.

I firmly believe that a step back is a step up. So, at the time it might seem like a large bummer or crop failure or something, but I firmly believe that there’s a reason for that. Maybe that reasoning is just learning – like I haven’t paid close enough attention and I need to learn more – or maybe it’s someone else’s learning.

Working with a group of people with a complementary skill set is incredible, and having the trust within that group. You move through things really quickly when that trust is there – when you’ve done that work, sharing and planning and working hard with each other, and putting in the work to have core operational values that everyone believes in. So, it’s not just my belief, it’s the organization’s belief and something that we’re all working towards. •

Q&A with Kelly Daynard

To hear our full interview with Kelly, visit agwomen.ca

Farm

& Food Care Ontario’s Kelly Daynard is dedicated to broadening Canadians’ understanding of food and farming.

By Brett Ruffell

In her long-time role as executive director of Farm & Food Care Ontario, Kelly Daynard has been a dedicated public trust advocate. She shares meaningful stories and information with consumers to broaden their understanding of Canadian food and farming. This includes bringing people to farms both in person and virtually. She also introduces Canadians to the people behind their food through several innovative programs. And she goes above and beyond her role to further help the industry and her community.

In this interview, Daynard chats with agriculture editor Brett Ruffell about the importance of educating Canadians about their food, her insights on the future of agriculture and more.

A big part of your role is bringing the public onto farms, either virtually or in person. Can you talk about some of those projects and why you think they’re important?

I’ve always said that if we could take every single person in this country out to a farm, there would be no need for organizations like Farm & Food Care. And I think that would be a good problem to have. So, you know, in the case of our culinary colleges, the students, when they graduate, they really know how to cook but they don’t have a sense of where that product comes from. We really want to help build those connections so that when they are doing menu prepping in their careers ahead, they have a much greater understanding of where the food comes from.

It’s the same thing we do with registered dietitians, or cookbook authors, or chefs or recipe developers, you know, these people are in such a place of influence for talking to people about food. And it would be amazing if they all had a greater appreciation of where that carrot came from, or how that chicken breast was prepared. So, a lot of our work goes into that.

We’re a tiny little Canadian charity and we cannot physically take every single Canadian to a farm. So, we have a virtual reality website. People can actually go just in the comfort of their own laptop, or computer or phone and tour a farm virtually.

All of those projects connect together, we hope, to give people a much greater ability to reach out and ask a farmer where their food comes from. Because we have always believed that if you want to know where your

food comes from, why wouldn’t you go straight to the source? We want to be that person helping them find that source.

You’ve led a few interesting projects that introduced the public to the people behind their food. Tell us about some of those initiatives.

I think every single person in agriculture has an amazing story to tell. And that person, that urban consumer that we’re trying to reach, probably thinks of the primary producer but they don’t think about all of the other people directly related to that. So, Faces Behind Food is a social media campaign we do on Instagram and Facebook. We tell two stories a week about people across Canadian agriculture. It could be the new immigrant that is working in an egg processing facility, or it could be a fellow who’s been a hoof trimmer for his entire career, or it could be a milk truck driver, or it could be a chef. You know, agriculture is so diverse. We have set out to tell those stories, and they get some really great traction.

We interviewed a new Canadian a couple of years ago, who works at one of Canada’s biggest mushroom farms. And his wife had just immigrated from India. And he was working in this mushroom facility. And we posted his profile on Faces Behind Food. He got involved in the comments. And there were hundreds of comments on his post welcoming

“If I could see a Farm & Food Care in every province by the time I retire, I that would make me really happy.”

him into Canada, inviting him and his wife over for dinner. I think we gained about 200 followers from India that week, which also made me smile.

But then that project also morphed into a side project called More than a Migrant Worker, which we work on with the Ontario Fruit and

Vegetable Growers in the early days of COVID. You know, Canada depends on seasonal workers to come here and grow our fruits and vegetables. A they weren’t getting here due to borders being closed. But when they were here, people weren’t understanding how critical they were. And some of them were getting some pretty negative treatment in their communities.

So, we started this More than a Migrant Worker project where we’re going out to farms, interviewing those seasonal workers from from the Caribbean, from Mexico, about how important their careers are to their families back home. But then also talking about the role they play. I mean, I would not have asparagus right now in my local farmers market without those lovely people harvesting it right now.

What would you like to see more of in agriculture?

If I could see a Farm & Food Care in every province by the time I retire, I that would make me really happy. Our sister group in Saskatchewan is doing some increasingly great work in Western Canada and our sister group in Prince Edward Island is doing some great work down there. But I really feel a need for an organization like Farm & Food Care in all provinces. I think that a group like ours gets added credibility with consumers

because we’re not selling anything. I’m just in the business of providing information. I think that consumers and the audiences that we attract really value that because I’m not going to tell them what to buy or how to buy. I’m just going to give them a bit more information so that they can go to the grocery store with a bit of an educated knowledge.

Why do you think it’s important to celebrate the achievements of women in ag?

I think there are some amazing women from coast to coast in this country who are doing some more behind the scenes work. And if an award like this celebrates those unsung heroes, then I’m absolutely for it.

Any hidden talents?

The one thing I do outside of agricultural work is I’m a historical tour guide. I love learning about old buildings and the people that came before me and the city that I live in. So, a side gig of mine is serving as a volunteer historical tour guide in the city of Guelph. And on weekends, you’ll find me wandering the streets with people who have booked tours through the Guelph Arts Council talking about the fabulous people that came in Guelph hundreds of years before I was here. •

Q&A with Judith Nyiraneza

To hear our full interview with Judith, visit agwomen.ca

Judith Nyiraneza has dedicated more than two decades to soil science, with her love of agronomy and agriculture helping her network and collaborate.

By Bree Rody

Judith Nyiraneza is widely recognized as a leader and innovator in regenerative soil management. She has led or taken part in numerous national projects, including the Living Laboratory –Atlantic Canada project. She’s an active advocate for the Living Lab concept and is also highly invested in the next generation of soil scientists, having served as an adjunct professor at Dalhousie University and Laval University, and mentoring two summer students per year for the last decade.

In this conversation, Nyiraneza talks to agriculture editor Bree Rody about how her young life in Rwanda, which brought her an inherent appreciation for agriculture combined with an aptitude for science, led her toward that specific discipline in her academic career.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Can you tell me what led you down the path of agriculture and soil scientists? And what led you to AAFC?

I grew up in central-east Africa, in Rwanda. Agriculture is very important there. In high school, I was interested in science classes, but I wanted to pursue graduate studies in applied sciences. Agriculture was the best fit for that. I got an undergrad degree in agronomy, and I was lucky to have a scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in soil science. Then, I got a PhD in soil agronomics. After I obtained my PhD, I was a post-doc at the Quebec research centre with AAFC, and I have always been interested in assessing regenerative soil management practices and evaluating the impact on soil health and nutrient cycling. A position was opened with AAFC in Charlottetown, and that’s how I got here.

What does your day-to-day look like at your current role?

Currently, I’m working on a Living Lab project, which I’m leading. We are assessing different soil regenerative management practices, including cover cropping, the use of soil amendments, and reduced tillage intensity. As a soil scientist, I focus more on the impact on nitrogen cycling, soil health and crop productivity. My day-to-day tasks include, depending on the season, data analysis, statistical analysis, a lot of

meetings, and of course, a lot of writings – it could be presentations or scientific publications.

What do you like about your role and the research you’re doing?

What I like most is more the challenging side of my focus in a sense that the soil regenerative management practices are context-dependent. Every farm is different, and I’m always challenged and excited at the same time when it comes to data interpretation. There are so many factors affecting the results, which make a difference when you compare site-to-site.

And why is this something the average Canadian, or Canadian farmer, should care about?

Soil is not a renewable resource. We ask too much of the soil, to produce food, but in the long run, if we don’t regenerate the soil, the productivity will decrease, and we can negatively impact the environment. Yes, we want the soil to produce more, we input more in terms of nutrients, but if you don’t improve with regenerative management practices, no matter how much input you put in, you won’t see the productivity increasing.

What are some things that you foresee as either challenges or opportunities in this area, or things you’re looking forward to tackling in future years?

Agriculture is weather-dependent, and the weather is changing. So I think it’s going to be more challenging to minimize the impact on the environment and sustain crop productivity. I am seeing an extended collaboration among professionals. We need that collaboration, and also, we need to adapt to embrace new technologies. We hear about precision agriculture and people who are specialized in machine learning and AI, so we can now have an extended amount of information without even measuring the soil. The challenge now is to be able to interpret that information and to make sense, to tell the grower about the information we are obtaining. The future I’m seeing is extended collaboration.

How do you view yourself in the context of a team?

I think I am a good listener, and in a team, I value everyone’s contribution. That’s probably my biggest strength.

What is your proudest achievement of your career so far?

The list can be long – but I will try to summarize quickly. Most recently, I contributed significantly to the writing up of the Living Labs – Atlantic and the implementation of the project. This was a big project, and the beauty of the project is the collaboration between scientists and stakeholders to enhance soil health and water quality. At work, we have been focusing in the last [few] years on soil regenerative management practices. I think the research results help growers make informed decisions about what the options are to regenerate the soil, reduce the impact on the environment while sustaining crop productivity. We [also] provided tools to growers to manage phosphorus fertilizer efficiently. We identified critical values above which the phosphorus transport to the environment will increase in P.E.I., and also a critical value above which the potato crop will not respond to phosphorus fertilizer. So that really helped the growers reduce their inputs and save money. Another

project with the P.E.I. department of agriculture and land was initiated 25 years ago, and it’s called the P.E.I. soil quality monitoring project. My role is to coordinate data analysis and writing updated reports. What I enjoy more about this was that it can show growers the temporal and spatial variability of soil fertility-related parameters, such as soil pH, soil carbon and other nutrients. They can see what other changes are happening across time and change their management to improve. It’s hard to summarize all the achievements of 22 years, but those are just some examples.

What have been some of your biggest challenges or things to overcome?

Probably my biggest challenge was when I decided to attend a master’s program in an English-speaking environment when my English was not strong. I was offered an opportunity to study at Michigan State University. During my undergrad, I had taken only two English courses, and that was it. To be able to get admitted to Michigan State, I needed to [pass] two assessments. [My fellow students and I] spent six months preparing for those tests. After, we arrived in Michigan State in July. We took writing courses in the summer, and in September, we started the program. I found the beginning challenging, but what I

have learned from that is that if you consider something a challenge at the beginning, it can be turned into an opportunity.

Who have been some of your biggest mentors?

I have had many supervisors, and actually, most of them were women. For my honours thesis at the end of my bachelor’s degree, my supervisor was a woman. My supervisor for my master’s was a woman, and my postdoc supervisor was also a woman. I had such strong mentors, and I cannot take credit for everything I’ve learned.

From your undergraduate to now, have you found there’s more of a gender balance in your sector than in farming itself?

I would not say that it’s balanced. I think women are still underrepresented in my area of work. I would really like to see more girls considering to pursue their careers in agriculture. Considering the diversity of opportunities – people who enjoy being outside, there are jobs for them. People who enjoy science and economics, there are jobs for them.

Do you also find there are systemic barriers in place for new Canadians, or non-native English speakers?

I think Canada is well-positioned in terms of being a welcoming country, but if you have two candidates, one of whom is a native English speaker and another for whom it is their second, third or fourth language, then the person who has to overcome those barriers has to work harder.

When you work with people you mentor, what are some of the biggest pieces of advice you pass down?

I tend to focus on telling them that no one is perfect. If they like what they do, they will achieve their goals. I think it’s very important to collaborate and network with other students, because they can learn from each other. Language is one aspect, but if they like what they do, science and agronomists have a universal language. •

To hear our full interview with Darby, visit agwomen.ca

Vineland’s Darby McGrath succeeds by taking calculated risks and surmounting daily challenges.

By Alex Barnard

Darby McGrath has been working in horticulture in one way or another since she was 16. Now, as the vice-president of research and development at Vineland Research and Innovation Centre in Vineland, Ont., she is responsible for conducting and guiding research that benefits the horticulture industry – including some of the farms she worked on as a teenager. McGrath chatted with agriculture editor Alex Barnard about working with people you respect and enjoy being around, the daily challenge of thinking you deserve to be where you are, and asking “Why not you?” when you need a reminder that you do deserve to be there.

What do you like best about your role?

I have to say it’s the people and the projects. My team is amazing – I run a fairly large team of researchers, scientists, technicians, directors, what have you, and these are all people who are extremely interested in solving problems and challenges and opportunities. So, that part is really fun – just getting to connect with people, brainstorming on things, thinking of solutions. And then helping to guide the portfolio – that part I absolutely love.

Another part that is really fun for me is continuing to work in the industry. I consider myself having grown up in the industry. Now, being able to come back to some of the people with whom I used to work with on solutions to the challenges that they’re facing, or them coming to us with the issues as partners, clients, collaborators. It’s just really wonderful to get to continue to work here and work in a way where you can watch the results and the impact move out into the landscape.

What’s one of the biggest risks you’ve taken?

I think probably the biggest risk I’ve taken was considering this position that I’m in now. It was one of those things I was certainly interested in, but I didn’t feel like I was quite ready for. It’s a bit of a leap – you have to leap and hope that the net’s there. It was a calculated risk, of course, but it was a risk because I have a young family at home and there’s always lots to be done. So, just making sure that I had the bandwidth and capacity to do the job was something I spent a lot of time thinking about before I considered throwing my hat in the ring.

I would say, given that one of your co-workers – and one of the people you now supervise – nominated you for this award, you’ve got the backing of the folks who work with you.

Yeah, I think that was perhaps the nicest part of it – to feel that my team felt I was worthy of it. I’m a little awkward about accepting awards, I think it’s my nature, but that was so meaningful to me, because I have so much admiration for the person who nominated me as a researcher and for what they do for Canadian agriculture. Receiving a nomination from my own team was pretty surprising, and it’s something I’ll carry with me.

It’s always easier when other people are telling you you’ve done something good than it is to feel it yourself, isn’t it?

It’s true, and yet I tell my team, especially the women, that you have to be ready and willing to brag about yourself. Sometimes, you have to be your own advocate, and I should practice that habit more than I do. But it’s something that I’m always telling the people in my team: you have to be your biggest fan, you have to have your brag book ready.

Tell me about a particular challenge you’ve faced and what you learned from it.

I think I face challenges every day, and one of the things I face the most is feeling like I’m up to the challenges. I would say, since I was a kid, it’s something I have constantly grappled with – whether I should be where I am and sitting around the tables I’m sitting at. It’s a constant battle. I wouldn’t say it’s this big, monumental event; it’s the uphill battle of recognizing you deserve to be where you are. Every day, it’s having that self-awareness to say, “If not you, who else?”

That can be really hard, and women I’ve had these conversations with before have felt similar things, so the good news is I’m not totally alone in that. I don’t know that that’s ever going to go away. It’s just something you practice until you make it a habit, is the best way to put it. Sometimes you don’t feel like you’re ready for something and you just have to lean in and take it on anyways.

What is one piece of advice that you’ve received that really stuck with you?

I think the biggest message I’ve received is sort of the idea of “why not you?” This is something I laugh about with my mom because she feels badly when she hears me say it back to her now, but her advice to us as kids was: There’s always going to be someone better or smarter or faster than you. There always is. There’s a giant spectrum of people out there

with respect to capabilities. But to me, the point in that message, which she feels sounds so negative, was actually: You can’t benchmark yourself against that; everybody’s different, everyone has different capabilities. So, why not you? Why not step up and try this new thing? Because you’re not going to know until you try it. So, I think that’s a really important piece of advice.

And the flip side of that is to not be afraid of failure. You can’t do all the cool, exciting, innovative things without failing a lot along the

way. Recognizing or recasting those things not as failures, but as lessons is the way to think about it. But, frankly, they are failures – and there’s nothing wrong with that. Research does not always work; most of the time it doesn’t work, and there are lessons in that. So, being able to accept that you’re not always going to have the best answer or be the best at something, but that it’s important to keep trying those things. And recognize that a failure is nothing – it’s not always even a setback, it’s an important step along the way.

When you’re in the moment, of course, you always want to be successful, but if you don’t push you’re never going to know.

If you could go back to the beginning of your career, what advice would you give yourself?

My mantra is to enjoy the journey. I’m someone who’s always going at a very fast pace –that’s my default speed. I have so many wonderful memories now, but as you get older, you get more sentimental about those past things. Soak it all in, because things change, you’re going to change, the world is going to change. So, try to enjoy all the moments and the people that you get to meet along the way. •

Q&A with Heather Wilson

To hear our full interview with Heather, visit agwomen.ca

Heather

By Bree Rody

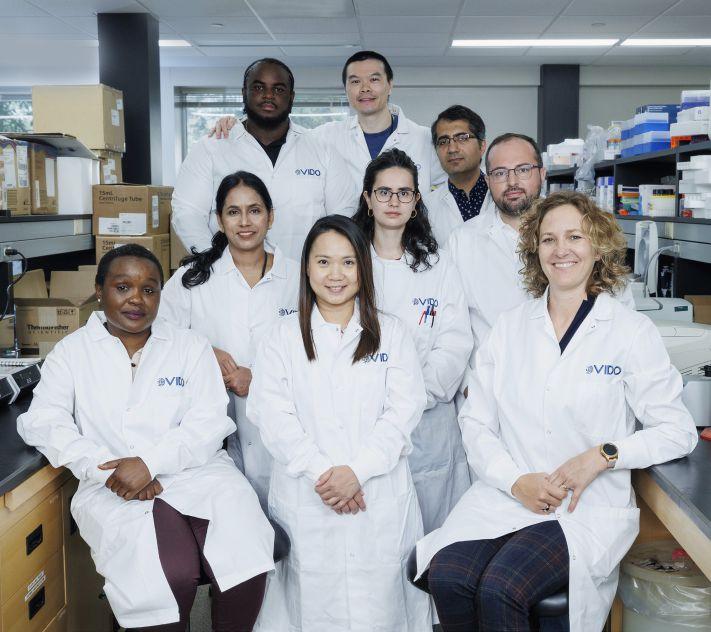

Saskatchewan-based Heather Wilson is a research scientist and program leader in the vaccine formulation and delivery group at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization, or VIDO. She’s also an adjunct professor at the University of Saskatchewan in the department of veterinary microbiology and the school of public health. She’s described as a dedicated supervisor and mentor, having previously mentored or currently mentoring four post-doctoral fellows, four master’s students, eight PhD students, three technicians, four project students and a half-dozen summer students.

In this episode, Wilson and agriculture editor Bree Rody discuss her views on leadership and mentorship, gaining the confidence to navigate tough processes such as grant-writing and networking and why it’s important to recognize one’s own strengths and weaknesses.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What led you from your education to this very specific focus and career path?

I got all my post-high school education at the University of Saskatchewan. I got my undergrad in biochemistry, which I found very interesting. Gene expression changes became very popular when I was finished – people were looking at gene expression changes after vaccination. So, then I moved to do my post-doctoral work at what was back then called the Veterinary Infectious Disease Organization, which is now the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization, or VIDO. It’s on the same campus, but that was the switch from biochemistry to immunology. I did some work looking at the neonate to the mom. I was originally looking at cattle, but they’re a bit selfish because they’ll only have one calf. So I started looking at pigs, because there will be 14 to 20 piglets, so there’s lots of room to do some different groups while keeping the genetics very similar. From there, it moved onto learning more about the pig industry and the nuances there. I didn’t grow up with cattle, I grew up with horses – I didn’t really know too much about farming, but then I married a farmer. He’s got a mixed grain and black angus cattle farm. After I

moved into the pig and learned more about the industry, I started to understand that there’s different nuances and different husbandry practices, and if you really pay attention, you can adapt what we’re doing for vaccine development so that it’s amenable to the current husbandry practices. That’s where we got into administering the vaccine, during the time of breeding, into the uterus. You’ve already rounded up the pigs, it’s something that’s happening all the time at regular intervals, which happen to be good intervals for vaccines. As long as we ensure the pig producers that we’re not negatively affecting sperm production or fertility, which we’re not, it’s a really interesting route for the industry.

With recent global concerns about ASFV or HPAI, do you feel like there’s more curiosity from outside your industry to learn more about vaccination strategies? Yes, but also, the low-hanging fruit has been grabbed. We’ve tried what we’ve tried, and we’re still making very good vaccines and good progress. But there are still some diseases out there that we’ve been trying to tackle for 100 years. It’s better to maybe learn some of the basic biology of the viruses or the bacteria and learn more about layering on, instead of just making a vaccine against the target, which is usually a protein, the protein has usually got sugar groups on it, so the different molecules are going to impact how you target that antigen. So we’re trying to learn more and integrate all that together. But [for example], porcine epidemic diarrhea virus swept through the country in North America a couple years ago. It didn’t make it into Saskatchewan, fortunately, but VIDO made a vaccine for that and was supplying it to Manitoba and, I believe, Alberta. We managed to keep it out of Saskatchewan with lots of work by the pig industry to understand transport and spread. We had to make a quick vaccine, and we managed. African Swine Fever is coming. Hopefully we can keep it out, but if it gets into the wild boar population, it’s going to be difficult to eradicate it. So, if you can’t actually handle the animals, can we get it out into the wild in a feed product? There are lots of things to think about when it comes to developing vaccines.

If you’re a woman in the agriculture industry, we have the financing and resources to help move your business forward.

Learn more at fcc.ca/WomenEntrepreneurs

DREAM. GROW. THRIVE.

It seems like mentorship is a really big part of what you do. As you’ve mentored, have you observed any shift in the gender balance? Is it split? Are things changing If you look at the classrooms – I do a little bit of teaching, but it’s not a part of the job – in the veterinary field, the classrooms have changed from basically male-dominated to fairly female-dominated now. Once you get into the graduate level, you also start seeing more people coming from all over the worlds, overseas, looking to do their master’s or their post-doctoral work. Most people’s labs are probably split fairly evenly, with certainly a very diverse workforce in terms of where people and their families are from. I think it’s great. You learn more about different farming practice, what producers do in different countries – you learn from everybody.

Who have some of your key mentors been – of any gender?

Dr. Bill Roesler was my PhD chemistry mentor. There were some very good people in his lab, as well. VIDO is a very good environment where everyone can work together. You can get support by hiring your own people, some of the pieces are quite expensive, so you can ask for a certain amount of time with technicians, or learn from people in other labs. It’s a great environment where you can learn from everybody. The veterinarians and the veterinary staff have been very good for teaching. There’s also a very good group at the Prairie Swine Centre that I’ve learned from, just outside of Saskatoon. They’ve been nice enough to let me do some of the vaccine work out there. Raelene Petracek at the Prairie Swine Centre, Colette Wheler at the animal care facility at VIDO – there’s been lots of people whom I’ve learned from.

Applying for grants is a big part of your work – can you share what you’ve learned about that process?

You don’t really learn how to write a grant when you’re in university. You don’t know how to do it until you’re in the middle of it – you get a couple back and you realize you scored pretty low. You get copies of other grants and see how they did and you learned from them. We’ve just started about 10 years ago doing [internal review]

which has increased how well the grants are written, and it’s increased our success rate. Some people are really good at writing, and some learn as they go, and I think I’m more of the latter. I think I’d never go back and read some of my old grants. It is a grind to apply for grants to keep the lab going. I’ve got friends who are in the non-university world, and they’re constantly surprised at how much work it is to keep going after the soft money.

You’ve done a lot of public speaking, most recently in Brazil. Is that something you’ve always had a knack for, or did you have to learn?

I remember being quite nervous the first view times. As a student, you’re scared you’re going to be attacked, because you’ve heard that’s what it’s like. You have to try to remember to find your audience. I find these kind of talks [podcast interviews] are more challenging for me, because I find it hard to bring it to a level where you’re interested and I’m not losing you. If I can get into using the science words, it’s a bit easier. There’s the science talks, the immunology talks, the producer talks – you have to learn your audience.

What do you think is your biggest strength as a person that have allowed you, and VIDO, to flourish?

I think I’m friendly and easy to talk to. People think of scientists as perhaps stiff. When people get to know me, it’s easy to talk to me. It makes it easier to visit with people.

Have you ever felt like being a woman in agriculture defines you?

Not as a scientist. I’m married to a farmer, and I’m maybe more aware of it there. Of course, it is his job and not mine, but there will be times when the salesperson will not even talk to me or engage with me. But I do appreciate that it would be very difficult to be othered constantly. I have not felt that, really. I think it’s still there. There’s still the “boys club” on every level of society, but I think with more and more women on the lower levels who then keep going up and up and up, and we see ourselves more in boardrooms, as CEOs and the leads of the labs… I think we’re getting there. We’ve still got a ways to go, especially for those from overseas or those who are non-white. It’s certainly more of a culture shock for them. •

7, 2023 LIVE EVENT I 1:00PM ET

INSPIRE | LEARN | LEAD | CONNECT

Register today for this unique live event coming to Hamilton.

Join us to hear from today’s most influential female leaders in Canadian agriculture.

This year, six IWCA honourees were chosen by our team. On November 7, 2023 at 1:00pm ET, they come together with other prominent trailblazers in agriculture to share their experiences, life lessons and more for the live 2023 IWCA Summit.

Join us for an afternoon of interactive discussions as they share their experience, offer guidance and discuss their journey in agriculture.

John Deere is proud to sponsor the Influential Women in Canadian Ag Summit.