Focus on: FARM FINANCES

Insights to help position your farm for success

Annex Business Media’s agricultural publications are hosting four free, live webinars with industry experts discussing key topics in farm financial management.

Part 1: Business Risk Management – A fact-based review and analysis

Part 2: Transitioning Your Farm - Opening the door to your transition

Part 3: Using Data in Ag for financial management

Recorded sessions now available on-demand at www.topcropmanager.com/webinars

Part 4: Utilizing Benchmark Information to Focus Your Farm Operation

JOIN US - June 10 - 1pm MT/3pm ET

SCAN QR CODE with phone camera or visit link below to register today for the series! A reminder email will be sent to you for each webinar.

There is no charge for qualified readers.

ALEX BARNARD ASSOCIATE EDITOR, AGRICULTURE

FEEDING FOR THE FUTURE

You are what you eat.” We hear this often in regards to human diet and – while I might not look like a donut – it’s true that what we consume can have significant and far-reaching effects on our lives, for good and bad. The same is true for crops. Properly managed, crop nutrition can help mitigate stresses caused by weather, disease and insect pests. The right nutrients can turn a good crop into a great one. But with so many different elements, products and considerations to keep in mind, determining what and how to feed your crop can become overwhelming.

These pages don’t hold all the answers, but we hope they serve as a good starting point for those looking to improve their crop’s nutrition.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) feed off plants and in turn help plants better access soil nutrients in a symbiotic relationship. Carolyn King’s story on page 4 describes two different projects examining how AMF communities react to inoculants and how they might be manipulated – or if they should be.

Bruce Barker’s story on page 12 discusses a much-needed update to nitrogen fertilizer recommendations for modern Manitoba corn cultivars. These high-yielding hybrids have outpaced the recommendations from the Manitoba Fertility Guide, so former University of Manitoba professor Don Flaten and MSc student Lanny Gardiner set to work developing new and improved nitrogen fertility guidelines.

As you’ll read on page 18, the body of evidence for silicon’s benefits to stressed crops continues to grow. While not all plants can absorb silicon in a usable way, Richard Bélanger and his research group at Université Laval are trying to add canola to the list of crops that can.

And that’s just a fraction of what you’ll find in this issue. In the world of crop nutrition, there’s something for every crop and most every situation – though you’ll know best what will suit your operation. As we hit this dry growing season’s midpoint, we wish you adequate rain and low pest pressure – and, as always, the best of luck.

ON THE COVER:

University of Manitoba MSc student Lanny Gardiner sidedressing UAN 28-0-0 on corn at the V4 stage. PHOTO COURTESY OF DON FLATEN.

UNEARTHING COMPLEXITIES

Exploring the effects of mycorrhizal inoculants.

by Carolyn King

Soil fungi called arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are known to provide vital benefits to plants. So the use of commercial AMF inoculants in crop production is increasing. But we still have much to learn about the impacts of these inoculants on a soil’s resident AMF community and about when the inoculants are likely to be beneficial. Scientists Fran Walley and Miranda Hart are both investigating these issues, but from different perspectives.

“Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi occur naturally almost everywhere – certainly in agricultural soils. AMF have a very close relationship with plants, living inside the roots of most plants on the planet. In fact, the evidence suggests that plants and these fungi evolved together from the beginning, as plants left aquatic environments and moved onto the land,” notes Walley, a professor of soil science at the University of Saskatchewan.

Mycorrhizae are propagated by spores or fungal threads called hyphae. These propagules infect plant roots, but instead of causing disease, the fungi work with the plant for mutual benefits.

“The fungi get their food and nutrition from the plant. In re -

turn, the fungi help the plant by doing different functions,” says Hart, a professor of biology at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus. “For example, they are better at acquiring certain nutrients than plant roots, and they can also protect against pathogens.”

Walley explains that AMF hyphae extend out beyond the root into the soil. “The super-thin hyphae can get into little nooks and crannies in the soil and soil micropores that roots can’t access. They really expand the volume of soil that the plant can explore.” AMF are particularly useful for capturing relatively immobile nutrients like phosphorus.

Digging into inoculant impacts

“The plant-AMF relationship is amazingly important for crop production. If you go to any field with crops like wheat or peas, virtually every one of those roots will have these fungi. And yet

ABOVE: Tillage can disrupt AMF hyphae in the soil, which can reduce AMF populations when combined with non-host crops.

PHOTO

we mostly ignore this relationship. We know very little about how agricultural practices affect it,” Walley notes.

“I think we should be interested in anything that can disrupt this extraordinary and extraordinarily beneficial relationship.”

Walley and her research group have been conducting AMF studies over the years, including recent research on commercial AMF inoculants for field crops.

“For years there was this idea: what if we could produce a commercial AMF inoculant for field crops? But people were unable to grow AMF in a typical lab situation, such as culturing them in a flask, because these fungi are so reliant on their host plant. However, researchers worked out how to culture one particular AMF species in a way that produces the vast amount of spores needed to develop commercial inoculants for field crops. So the currently available inoculants all contain that same species,” she notes.

“However, a whole host of different types of AMF are in our soils. So I wondered: What happens if we add a single-source inoculant into the soil? What impact might it have to release a non-indigenous strain into our soils, which already contain a very healthy and vibrant population of various AMF? Is it possible that the inoculant might have a negative effect on the AMF community structure that already exists and has been there as the soil developed?”

Growth chamber experiments by her research group show that some AMF species are better than others at enhancing plant growth. “So, if we are going to add a single AMF species to the soil, that AMF species better be good at enhancing nutrient uptake, for instance, and hopefully better than what is already in the soil.”

In a recent field experiment, Walley’s group explored an important aspect of this issue. “We were asking the question: if we use this commercial inoculant, will it have an impact on the native community of AMF species? Is this single AMF species going to start to take over this system?”

This three-year experiment took place in Swift Current (Brown soils), Scott (Dark Brown), Outlook (Dark Brown) and Melfort (Black). The study team, with then-PhD student Nazrul Islam, took soil cores at each of the four sites and re-installed those cores at all the sites. Each core was encased in an open-ended aluminum cylinder. At each site, a commercial AMF inoculant was applied to half of the cores in year one; the rest of the cores were used as controls. Then a pea/wheat/pea rotation was grown in the cores. No AMF inoculant was applied in years two or three.

Soil, climate and the indigenous AMF community all influenced the inoculant’s persistence and its impacts on that community. The inoculant was detectable for three growing seasons at the Swift Current and Outlook sites, two seasons at Melfort, and one at Scott.

“The inoculant shifted the AMF community, but in a way that was not predictable. At some sites there was a fairly big shift in the community composition, whereas at other sites there was only a modest shift that didn’t necessarily persist,” Walley notes.

“Bottom line, the study showed that using an AMF inoculant can impact the AMF community composition. Whether that impact will be positive or negative [for the soil microbial community and for crop production] is yet to be determined. So the next step is to ask: Do we need to worry about that impact? And that is still an unanswered question.”

She adds, “I love the idea of having a commercial inoculant because AMF are so important. But we don’t fully understand yet whether the impacts will be consistently good, or neutral, or potentially bad, if native communities are negatively affected.”

Another angle on AMF inoculants

Hart is concerned that AMF inoculants could spread beyond crop fields and pose a threat to indigenous AMF communities and the native plants that depend on them.

“The reason I’m a biologist is because I love nature and wilderness and I want to preserve nature. I started wondering if these inoculants might be invasive species, as opposed to just management tools, because they are living organisms. And the more I got into it, I realized that there wasn’t any real legislation or rules about their use, and that seemed worrisome to me,” she says.

“One of the things that most worries me is that these inoculants are being marketed as being beneficial for soils. But the reality is there is not enough research to say that yet.”

Hart explains, “The evidence from my work shows that inoculation can be inconsistent. Sometimes the inoculant doesn’t even establish. Sometimes it establishes and you still don’t see an effect. And sometimes you’ll see an improvement in crop performance. For example, I did some [horticultural] studies where there was an improvement in crop establishment post-transplant. Some studies have shown small increases in yield. And then sometimes inoculation is detrimental, with decreases in biomass.”

According to Hart, not a lot of research has been done to evaluate the risk to natural areas from AMF inoculants. That is partly

Walley’s three-year AMF study used a pea/wheat/pea rotation at all four sites.

PHOTO BY TOP CROP MANAGER.

because tracking the persistence and spread of inoculant strains has been difficult because AMF species closely related to the inoculant strains occur naturally in soils all over the world. Fortunately, recent advances in molecular tools are enabling Hart’s group and others to track the inoculant strains.

Similar to Walley’s study, Hart’s research shows that an inoculant’s effect on an indigenous fungal community is not easily predictable. “In some cases, the inoculated fungus can replace the pre-existing community. In some cases, the fungus establishes but doesn’t really change the fungal biodiversity. And sometimes it fails to establish. But it’s not clear what conditions foster each outcome.”

Hart is working on various field and greenhouse AMF studies. “I’m trying to figure out how microbes spread, how fast they spread, how far they spread. So when you use an inoculant, are there conditions where the fungus is going to spread uncontrolled? Could we manipulate our cover crops to keep it within an area?”

She cautions, “I think you can mitigate some of the onsite spread of an inoculant, but I don’t know that it is going to be successful in the big picture. Microbes move in all sorts of ways – in the water table, on animals, in the atmosphere; they move between continents.”

Her field studies include vineyards, grain cropping systems and natural areas. She works with local farmers who are already applying AMF inoculants. “Here in the Okanagan Valley, grape vine growers are very keen to try different sustainable approaches, and many are using inoculants.”

Hart is also investigating how AMF inoculants affect the functioning of a natural soil ecosystem once the inoculated fungi establish there. “Let’s say these fungi get in and they change native soil communities. That sounds bad, but if the soil ecosystem is still functioning properly then maybe it’s not such a bad thing after all. Or conversely, maybe they are completely changing how that soil ecosystem works. We don’t know. So I’m trying to look at unintended consequences below ground.”

Considerations for growers

Since crop response to AMF inoculants can vary considerably depending on such factors as the existing soil microbial community, host crop, soil properties and weather, it will be hard to predict whether AMF inoculation will provide a crop benefit in your field.

If you are planning to use an AMF inoculant, Walley suggests a strip trial could be helpful. Perhaps the indigenous AMF community that has developed under your particular field conditions is actually well suited to those conditions and will outperform a non-native inoculant.

She doesn’t have a recipe for increasing AMF populations in your fields. “Although more and more AMF research has been done over the years, we still actually know very little about the impact of different agricultural practices on AMF communities. I’m not sure I can point to research – certainly not research that I’ve done – that says here are the end strategies you can take to increase AMF.”

However, she can point to several factors that will influence your AMF populations.

“Some crops are not hosts to AMFs. Anything in the Brassica family, such as canola or mustard, is a non-host crop, so it is not unusual to have a slight reduction in the number of viable AMF propagules after a Brassica crop. Although wheat is a host, it is not highly responsive to AMF, in part because it has a really vibrant and extensive root system. Crops like peas or flax are highly mycorrhizal because their roots tend to be coarser and not as extensive as some cereal crops,” she explains.

“Tillage can disrupt the AMF hyphae in the soil. If that is

combined with growing a canola crop or having a non-crop year where there are no host plants, a fallow year for instance, it could also reduce the AMF population. I’m fairly sure that long-term flooding might have a similar effect.

“So the number of infective AMF propagules in the soil could decline over time due to any of those circumstances. And you could imagine a scenario where you’re planning to grow a highly mycorrhizal crop following a year where the AMF propagules might have declined. So perhaps those are conditions where using an AMF inoculant might be beneficial.”

But Walley points out, “Even if the propagules have declined, AMF are always present. In fact, it would be very hard to find a field where there were none.”

From Hart’s perspective, using AMF inoculants in a field situation is risky until we learn more about AMF biology and ecology. “Do you want to introduce foreign strains into an ecosystem, knowing that you can’t control what happens, knowing that you don’t know what’s going to happen to soil biodiversity?”

For now, Hart thinks an inoculant should be used only in specific situations where AMF are not already present. One example would be horticultural crops grown indoors in hydroponic systems. “Using AMF inoculants in that situation totally makes sense. Number one, the plants don’t have any mycorrhizal fungi to begin with, so if you give them some mycorrhizae, they will always do better. And number two, the fungi are confined, so they are not going to spread uncontrolled in the environment.”

Walley hopes to do more AMF studies in the near future so crop growers will have better information about how to nurture and enhance the AMF community in their fields. “We really need a better understanding of what impacts all our cropping practices and management systems are having on AMF. Part of having a healthy soil is promoting these really great organisms that plants rely on very heavily.”

Walley’s study examined the impact of inoculants on native AMF communities in Brown, Dark Brown and Black soils.

LIMITED IMPACT WITH CHOCOLATE SPOT DISEASE

Research finds plenty of disease but not much impact on faba bean.

by Bruce Barker

So far, so good. That’s the good news on chocolate spot disease affecting faba bean crops in Western Canada. While chocolate spot has been widely found on the Prairies, a four-year research study found only minor impacts on faba bean production.

“We found chocolate spot in every field that we surveyed but the incidence and severity were quite low,” says Syama Chatterton, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta.

Chocolate spot disease on faba bean is caused by two different pathogens. Botrytis fabae is considered more aggressive and destructive. Botrytis cinereal is less aggressive, and can also affect lentils and other pulses. Other pathogens, such as Alternaria spp., Fusarium spp. and Stemphylium spp. can often be found at the same time in the field. All of these species can cause leaf spotting on faba bean.

In 2015, when acreage of faba bean was expanding on the Prairies, very little research on conditions favouring diseases of faba bean had been performed in the area. In response, Chatterton received funding for a three-year study looking at the incidence and severity of chocolate spot and other foliar diseases on faba bean in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Her collaborators were Sabine Banniza at the University of Saskatchewan and Robyne Davidson, pulse research scientist formerly with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry and now with Lakeland College. Funding was provided by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture and the Canadian Agriculture Partnership, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Alberta Pulse Growers and Western Grains Research Foundation.

The research also looked at the environmental conditions leading to Botrytis spore release and infection in the field and the effect of leaf wetness duration, temperature and inoculum concentration on disease development.

Overall, 103 commercial faba bean fields were surveyed from 2017 to 2019 in Alberta and Saskatchewan. All but one faba bean field surveyed had foliar lesions at the time of surveying during flowering in late July to mid-August. Disease severity (DS) was very low across all fields, with small lesions covering one to 10 per cent of the plant surface in 2017 and 2018. Disease severity was higher in 2019 with some coalesced lesions, covering 21 to 31 per cent of the leaf surface and some defoliation. Average disease severity ranged from 1.7 to 2.7 (on scale of 1 to 5, with a minimum average DS of 1 to a maximum of 5). There were always more lesions in the lower canopy compared to the upper canopy.

LEFT: Chocolate spot with Stemphylium blight.

BOTTOM LEFT: Chocolate spot with non-aggressive and aggressive lesions.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Alternaria leaf spot.

“The symptoms can look really bad with these big black blobs on the leaves but we never really saw the disease take off to the point where it was taking over the entire plant,” Chatterton says.

In the survey, Botrytis spp. were found in 11.1 per cent of isolates, Stemphylium spp. in 24.4 per cent, and Alternaria spp. in 43.3 per cent of the total fungi isolated. Of the Botrytis spp., B. cinereal was found in 53 per cent of isolates and B. fabae in 19 per cent. B. euroamericanawas found in six per cent, and another 23 isolates could not be identified.

“One of the most interesting findings was the high level of Stemphylium and Alternaria species on faba bean. I think what is happening is that those pathogens are piggybacking on Botrytis lesions to infect the faba bean plant,” Chatterton says. “Those two pathogens are not considered to be a problem on faba bean, so there needs to be further research to see what role they play in disease development.”

There was no difference in the susceptibility of a tannin versus non-tannin faba bean cultivar to chocolate spot.

The research found that that temperature and dew point temperature significantly affected disease development. Cool night time temperatures of 10 C to 15 C and exposure to dew point temperature of 5 C for three hours favoured infection. However, weather could not be directly correlated to disease severity, as there was too much variability in the patterns from year to year.

Fungicides haven’t provided a large benefit

Over five years from 2016 through 2019, and at four locations in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Davidson looked at the impact of foliar fungicides applied at 50 per cent flowering on disease severity and yield. Two years – 2017 and 2018 – were drier and had lower chocolate spot severity, while 2016, 2019 and 2020 favoured disease development.

“Generally, I would say that fungicides weren’t that effective as a whole,” Davidson says. “Visually, disease severity was lower with fungicide application but I didn’t see much of a yield increase. When I crunched the numbers at eight to nine dollars [per bushel] faba beans, the economics didn’t work out.”

Davidson says that chocolate spot lesions can look bad, but because the disease generally develops later in the growing season, and faba bean plants are fairly robust, losing some leaves doesn’t seem to impact yield. If a grower does decide to apply a fungicide, leaving a check strip to compare yield and economics would be a good idea, given the results of this research.

“In 2020, we had faba beans growing six- to seven-feet tall. There was definitely chocolate spot, but it didn’t seem to have much impact on the faba beans,” Davidson says. “We’ve tried to find out if the chocolate spot problem is really a problem, and to this point, it probably isn’t, but that might change if faba bean acreage goes back up or there is a shift to the more aggressive Botrytis fabae pathogen.”

ENHANCING THE DURABILITY OF CLUBROOT RESISTANCE

Multiple genes and extended crop rotations provide longevity of resistance, reduction in inoculum levels and yield protection.

by Donna Fleury

For canola growers, clubroot remains a serious threat as it continues to spread in Western Canada. Although cultivar resistance is the key to clubroot management, several “new” virulent pathotypes were identified that can break resistance in the first-generation clubroot-resistant (CR) canola varieties. Researchers and industry continue to look for new strategies to improve resistance performance and durability.

“Back in 2012, we started to see more clubroot disease in some clubroot-resistant varieties in a few fields in Alberta, along with reports of several new pathotypes that were virulent on all current resistant varieties in the marketplace,” explains Gary Peng, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon.

“We worked with a breeding company to incorporate one of our AAFC resistance genes with one from the University of Alberta, along with an existing gene from one of the company’s varieties, to look at the potential of using multiple genes to broaden the resistance spectrum and durability against different pathotypes.”

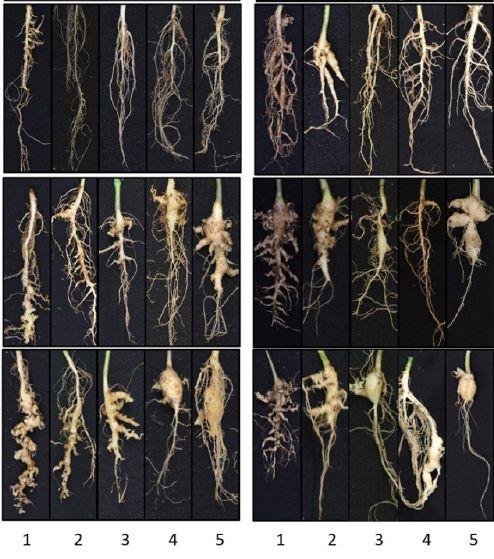

Peng and his team then initiated a unique three-year study in 2016 to investigate the efficacy, performance and durability of canola lines carrying single and multiple CR genes. The CR genes were tested against “new” pathotype 5X and pathotype 3H (old pathotype 3) populations under simulated intensive canolagrowing conditions. Researchers also wanted to look at the mechanisms of resistance for multiple genes versus single genes.

For the study, 20 canola-quality Brassica napus inbred and hybrid lines/varieties carrying single-, double- and triple-CR genes were produced by a breeding company. The varieties Westar and 45H29, both susceptible to newly identified pathotype 5X, were included as controls. 45H29 is resistant to old pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8. The lines were assessed for resistance against field populations of 5X using inoculum from Stephen Strelkov’s lab at the University of Alberta. A similar second durability study followed with the 3H pathotype commonly found on the Prairies.

The study was conducted under controlled greenhouse conditions to simulate an intensive canola rotation over five generations, which took about 18 months for each pathotype and repeated once. Using a continuous rotation of each variety, the clubroot galls were collected and put back into the soil after each generation to determine the level of inoculum returned to the soil and disease severity in the crops. In the study, two different types of soil infestation were compared for the common 3H pathotype: one with a very high level of inoculum to represent the worst cas-

Resistance performance and durability of canola varieties carrying single and double CR genes against pathotype 5X under repeated exposure to the same pathogen population.

es in Alberta, where the first-generation of resistance had deteriorated, and a second with a much lower level of inoculum, more representative of Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“From the study, only two of the double-gene hybrid varieties were moderately resistant against all populations of 5X,” Peng says. “None of the single-gene varieties seemed to have sufficient resistance to 5X. Although we are still trying to fully understand the genetic composition, the CR genes on chromosome A8 (CRB) were effective to the old pathotype 3H, but less so or variable to the new pathotype 5X depending on the pathogen population.

“However, when CR genes of A8 (CRB) were combined with one of the CR genes on chromosome A3 (Rcr1 or CRM), moderate but consistent resistance was achieved against all 5X populations. The A8 region is fairly narrow but can include more than one

PHOTO COURTESY OF GARY PENG.

gene, and is the area that provides moderate resistance against some other pathotypes. The two varieties with different combinations of two genes on A3 and A8 were the ones providing a moderate level of resistance to 5X.”

Another component of the project included a study of the molecular mechanisms of multi-gene versus single-gene resistance using RNA sequencing. Although researchers are still completing the analysis, early results show that, in response to 5X infection, many genes involved in plant immunity pathways were more strongly activated in varieties carrying these two CR genes, relative to those controlled by either of the single CR genes alone.

In other words, although similar pathways relating to plant defenses may be activated, the level or intensity of the response is stronger in the double-gene hybrids.

“In terms of performance and durability, the moderate resistance of the double genes against 5X never seemed to be significantly eroded over the study,” Peng says. “We also saw that the resistance did not change the inoculum population much except for in one case, even with the return of moderate-sized clubroot galls to the soil. In only one of the four experiments did we see a statistically significant trend of inoculum reduction, with lower inoculum levels resulting in the soil over the generations. Although the disease severity changes were not significant in the study, the single breeding lines were always higher in disease severity than the double-gene varieties.”

In the study of repeated exposure to pathotype 3H, disease levels clearly crept up over the five generations of the single-gene varieties under high initial inoculum levels, particularly with those that carry the resistance on the A8 chromosome. However, with the double-gene varieties, there was very little change across the five generations at high inoculum loads, with only a trace level of disease showing up in the final generation.

At the lower levels of inoculum, the efficacy of resistance seemed to be maintained among all CR varieties, regardless of the number of CR genes involved. Further research on resistance against additional new pathotypes (2B and 3A, for example) is necessary to confirm the validity of this multi-genic strategy for enhanced resistance efficacy and durability.

Good stewardship practices for clubroot management remain one of the best tools growers can use.

The study results highlight the value of using multi-gene resistance or stacked CR genes of different modes of action for resistance performance and durability. “At the same time, maintaining low levels of inoculum in fields using longer rotations and other strategies, such as resistant varieties and patch treatments, is also important to reduce the load of resting spores in heavily infested fields,” Peng says. “Various studies, including some in commercial fields, have shown that extended rotations of at least two years between canola crops will provide a dramatic reduction in inoculum level.

“Extending rotations provides growers with the biggest bang for their buck, and a two-year break in canola would give close to a 90 per cent reduction of pathogen inoculum. With reduced inoculum levels, the resistant variety will perform with higher efficacy and perhaps longer durability.”

Good stewardship practices for clubroot management remain one of the best tools growers can use for longevity of resistance, reduction in inoculum levels and yield protection. In Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where clubroot is still found in a relatively small number of fields, prevention remains the number one priority. Limiting the spread of the disease from farm to farm still goes a long way.

For most of the other areas, the first-generation of varieties can still be effective due to their efficacy against the predominant race types on the Prairies. The second-generation of resistant varieties with double genes or new genes may provide a wider spectrum of resistance in most of the fields. Peng notes that the task for all of us going forward is to focus more on stewardship strategies against clubroot on the Prairies that will help these secondgeneration varieties perform well and for a longer duration.

Clubroot remains a serious threat as it continues to spread across Western Canada.

NITROGEN FERTILIZATION FOR MODERN CORN HYBRIDS

Research updating the 4Rs of nitrogen management.

by Bruce Barker

As corn hybrids continue to push yield boundaries in Manitoba, so are they pushing nitrogen (N) fertility recommendations. The N recommendation from the 2007 edition of the Manitoba Fertility Guide for a 130-bushel per acre corn crop is 195 pounds of N per acre (lb. N/ac) with a nitrate-N soil test of 30 lb. N. But corn yields in Manitoba have been hitting 200 bushels per acre over the last few years.

“There was a need to revisit nitrogen recommendations because of the high yields that corn growers are hitting in Manitoba,” says Don Flaten, soil scientist and retired professor at the University of Manitoba.

The last N research on corn at the University of Manitoba was done in 1981 through 1983. The 2007 Manitoba Soil Fertility Guide’s N fertilizer recommendations suggest that corn is taking up 1.7 to 2.0 lb. N per bushel (N/bu). For a 200-bushel corn crop, these recommendations would suggest 340 to 400 lb. N/ac is required.

In 2018, MSc student Lanny Gardiner, supervised by Flaten, started a two-year trial looking at all four “Rs” in the 4R Nutrient Stewardship program for corn production in Mani -

toba – rate, source, timing and placement. Most of the results have been analyzed and there are plans for the final report to be made publicly available.

These experiments were conducted across a total of 17 locations in southern Manitoba during the 2018 and 2019 growing seasons. The studies were conducted at two levels of intensity, gold and silver. The four “gold” level sites were managed entirely by the University of Manitoba and included more treatments and measurements than for the 13 “silver” level sites, which were hosted within commercial corn growers’ fields.

Overall, corn grain yields in 2018 and 2019 were limited by inadequate moisture at many of the field sites. Therefore, Flaten says, the results of this study need to be interpreted cautiously, recognizing that crop yield potential and N losses were probably smaller than usual during these two relatively dry growing seasons.

ABOVE: Karissa Render (University of Manitoba summer student) and Lanny Gardiner (MSc student) in the zero N control plot for their corn fertilization trial near Carman, Man.

PHOTOS

Smart Nutrition™ MAP+MST® granular fertilizer supplies your soil with all the sulfur and phosphate it needs, when your crop needs it. Using patented Micronized Sulfur Technology (MST), sulfur oxidizes faster allowing for earlier crop uptake — making the nutrients available to your crops when it’s needed most.

Learn how Smart Nutrition MAP+MST can boost your soil’s performance and maximize your ROI at SmartNutritionMST.com

Optimum rates of N

Economically optimal supplies of soil test N plus fertilizer N were determined using four methods. The optimal total supply of N varied with the method of calculation, ranging between 1.09 and 1.44 lb. N/bu for 11 site-years where the yield potential exceeded 130 bushels per acre (bu/ac), assuming prices of $4.50/bu for corn and $0.45/lb. for N fertilizer. The equivalent range of optimal N supplies for seven site-years with yields less than 130 bu/ac was 1.5 to 2.1 lb. N/bu.

Similar to the results of studies in the U.S., this study showed that situations with the potential for greater corn yields require less N per bushel at the optimum rate of N. However, the optimum supply of N on a per acre basis was remarkably similar for both yield groups, generally in the range of 150-190 lbs N/acre, including soil test plus fertilizer N. Part of the reason for this was the more efficient N use at the higher yielding site-years, but part was also due to more release (mineralization) of soil organic N during the growing season at the higher yielding site-years.

“There are pros and cons to each method of determining the optimum rate of N, but for typical yields of corn in Manitoba, which are approximately 140 bushels/acre, a total N supply (soil test N plus applied N) of 1.1 to 1.3 lbs N per bushel of target yield appears to be appropriate,” Flaten says.

For lower yielding sites, the range of 1.5 to 2.1 lbs N/bu is similar to the earlier research and guidelines found in the Manitoba Soil Fertility Guide.

Nitrogen sources applied at planting

At the four gold level site-years, additional treatments applied at planting included urea-based products with a physical coating (ESN) or chemical inhibitors (eNtrench-treated urea and SuperU). The five treatments were 1) pre-plant broadcast and incorporated ESN:Urea in a 1:1 blend, 2) pre-plant broadcast and incorporated SuperU, 3) pre-plant broadcast and incorporated eNtrench-treated urea, 4) post-plant broadcast SuperU, and 5) the standard management practice treatment of pre-plant urea broadcast and incorporated. Each of these treatments was applied at 80 and 120 lbs N/acre.

Within a similar rate of N fertilization application, there were no significant differences in corn grain yield among different sources and placements.

“This lack of difference between sources was not surprising, given that both growing seasons were relatively dry, resulting in low risk of N losses by leaching or denitrification,” Flaten says. “In addition, the relatively dry conditions resulted in the lowest rate of N used in these comparisons (80 lbs N/acre) being close to the optimum N rate determined in the rate study, making any potential yield response differences between sources very small and difficult to detect.” Furthermore, Flaten noted that benefits of enhanced efficiency fertilizers might have been larger if the fertilizers had been applied in fall, rather than spring.

Nitrogen sources for mid-season application

All 17 site-years included mid-season applications of UAN (280-0 liquid) applied with and without Agrotain urease inhibitor. The mid-season treatments were applied at V8 stage (mid-late July) with a Y-drop simulated application of 53 or 106 lbs N/acre in 2018 and 40 or 80 lbs N/acre in 2019, in addition to 40 lbs N/ acre applied at planting.

Yield increased when an additional 40 or 80 lbs N/acre in midseason was applied on top of the 40 lbs N/acre applied at planting. The statistical analyses showed no advantage to adding a urease inhibitor when mid-season N was surface applied in 2018 and 2019. Even though urease inhibitors often improve the efficiency of surface-applied urea or UAN fertilizer, Flaten

explains in the N rate portion of this study, the numerical difference in overall mean yield between the 80 and 120 lbs N/ acre applied at planting was only three bu/acre, which was not statistically significant.

“This shows that under the relatively dry conditions for this study, the response to N fertilizer application at rates above 80 lb/acre was minimal. As a result, a response to the Agrotaintreated UAN fertilizer compared to untreated urea at these rates would be unlikely,” he says.

Timing and placements

Across all 17 site-years, the split application of N, applying 40 lbs N/acre at planting and another 40 to 106 lbs N/acre side-dressed at V4 or tube dropped at V8, did not increase yield compared to applying similar or slightly smaller total rates of N at planting.

Once again, the dry weather during the 2018 and 2019 growing seasons probably contributed to this lack of benefit for split applications, because the risk of losing N applied at planting was very low, and inadequate moisture was also a substantial limitation for yield.

However, split application decreased yield in three of the 17 site-years where soil test nitrate concentrations were very low at less than 40 lbs N of soil test nitrate-N/acre to two feet at planting. Flaten says this illustrates that there is a downside risk of yield loss with split N applications if the corn crop is not supplied with sufficient N in the early part of the growing season.

University of Manitoba MSc student Lanny Gardiner sidedressing UAN 28-0-0 on corn at the V4 stage.

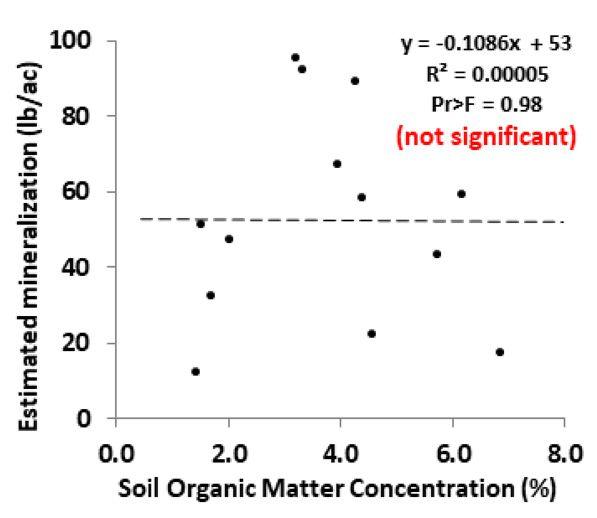

The relationship between soil test lab measurements (e.g., soil organic matter concentration and N released during 4 weeks of incubation at room temperature) and estimated mineralization of N from field measurements across 13 site-years was very poor and not statistically significant.

Applying more than 40 lbs N/acre at planting would be a way to mitigate the risks of early season N deficiency when planning for split application on soils with low levels of pre-plant N. In these trials, 40 lbs N/acre applied at planting was surface broadcast incorporated; it may also be beneficial to improve early season availability of N by banding near the seed row.

N management tools for corn growers and agronomists

Most soil tests measure residual nitrate-N that is only the immediately available N in soil.

However, the amount of N released from decomposition of soil organic matter (mineralization) during the growing season can be large. In this study, N mineralization varied from 12 to 95 lbs N/acre across the 13 site-years where N mineralization was estimated in 2018 and 2019, but other trials in Manitoba under more moist conditions have found much greater mineralization values. As mentioned previously, this variability in mineralization was one of the reasons for differences in the optimum rate of N fertilization from one site-year to another.

Flaten and Gardiner looked at 10 pre-plant soil test mineralization methods, including organic matter and a four-week incubation test, to see if they would help refine fertilizer recommendations. None were useful for predicting the soil’s capacity to mineralize additional N from soil organic matter under field conditions.

Two further tools that might be of benefit to corn growers

were also investigated. Data for the pre-sidedress nitrate test (PSNT) are still being processed to calibrate that test for Manitoba corn production. The purpose of this soil test is to enable corn growers to determine the appropriate rate of N to apply at the V4 stage, after accounting for loss of N through leaching and denitrification losses in a wet spring, or an increase of N through mineralization.

Pre-harvest stalk nitrate concentrations and late season leaf colour ratings data are also in the process of being analyzed. According to research conducted in Iowa, stalk nitrate concentrations less than 700 parts per million (ppm) indicate low to marginally sufficient N nutrition; whereas concentrations greater than 2,000 ppm indicate the plant has excessive N. Late-season leaf colour has been used as a diagnostic tool in South Dakota, where researchers have found that if the third and fourth leaf below the primary ear leaf were green (without any visual symptoms of N deficiency), yield should not have been limited due to lack of N.

Flaten says a post-harvest soil N test can also be used as an auditing tool for evaluating the nitrogen fertilization program for the crop that was recently harvested. In this study, postharvest soil samples were collected from N fertilizer rate treatments at eight of the site-years, with an additional five site-years having only the check plots post-harvest soil sampled.

Preliminary analyses of the relationship between the residual soil test data and the yield response data indicates that a postharvest nitrate-N test of less than 20 lbs N/acre to 24 inch soil depth indicates that the previous corn crop was probably deficient in N. A test value of 20-50 lbs N/ac probably indicates that the previous corn crop was not excessively fertilized. And residual soil test values greater than 50 lbs N/acre probably indicate that there was excess N available for the crop.

“The results will provide ... new nitrogen fertility guidelines and tools to help manage risks for our high-yielding corn hybrids.”

“Once the final report is completed, the results will provide corn growers and agronomists with new nitrogen fertility guidelines and tools to help manage agronomic, economic and environmental risks for our highyielding corn hybrids,” Flaten says.

A NEW APPROACH TO DIAMONDBACK MOTH CONTROL

Self-limiting moth could provide incidental benefits if used in the U.S.

by Bruce Barker

They breed, but female offspring don’t survive. That’s the technology behind Oxitec Ltd.’s insect control technology. The insects contain a self-limiting gene and, when this gene is passed on to their offspring, female offspring do not survive to adulthood, resulting in a reduction in the pest insect population. The technology was recently field-tested on diamondback moth by Anthony Shelton, a professor in the department of entomology at Cornell University in New York.

“Our research builds on the sterile insect technique for managing insects that was developed back in the 1950s and celebrated by Rachel Carson in her book, Silent Spring,” Shelton says. “Using genetic engineering is simply a more efficient method to get to the same end.”

After release of males of this strain, they find and mate with pest females, but the self-limiting gene passed to offspring prevents female caterpillars from surviving. With sustained releases, the pest population is suppressed in a targeted, ecologically sustainable way. After releases stop, the self-limiting insects decline and disappear from the environment within a few generations.

Open field trials were conducted in the summer of 2017 at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) Agriculture Experiment Station in Geneva, N.Y. These trials examined the ability of diamondback moth to survive and disperse in the field.

The researchers used the “mark-release-recapture” method. A fluorescent powder was used to mark each strain before release. The insects were later captured on pheromone traps. Each re -

The type of feeding damage that high populations of diamondback moth can potentially do to young canola plants.

leased group was then identified by the powder colour and a molecular marker in the engineered strain.

The field study results found good potential for control of diamondback moth outbreaks. The self-limiting male insects behaved similarly to their non-modified counterparts in ways like survival and distance travelled.

“Our mathematical models indicate that releasing the selflimiting strain would control a pest population without the use of supplementary insecticides, as was demonstrated in our greenhouse studies,” Shelton says.

This method can be applied to all kinds of insect pests, from the mosquitoes that transmit diseases, such as dengue and Zika, to moth caterpillars that destroy corn fields. For example, Oxitec implemented a pilot project in the Florida Keys in August 2020 using this self-limiting technology on Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The female A. aegypti mosquito is an invasive species found throughout the world that spreads dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. It poses an increasing threat. In 2020, there were localized outbreaks of dengue in the Keys.

The diamondback moth is common wherever Brassica crops are grown globally. The pest returns to Canada each year, but the severity varies considerably from year to year. Only low levels may successfully overwinter on the Prairies, and infestations primarily

PHOTOS COURTESY OF JOHN GAVLOSKI.

come from insects blown in on wind currents from the southern or western U.S. Early arrival on the Prairies can mean diamondback moths go through up to four generations in a year, building up to economically damaging levels.

John Gavloski, an entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, says the technology is unlikely to be implemented on the Prairies for diamondback moth control, given the sporadic nature of infestations here. “I see this as having potential for diamondback moth management in areas where [the moth] overwinters or is an annual concern. The feasibility of rearing and releasing male moths with the lethality gene in the Canadian Prairies may not be as great,” Gavloski explains.

Similar technology has been used in Canada on the codling moth in the Okanagan Valley, where the insect causes damage to apples and pears. The first sterile codling moths were released in the South Okanagan in 1994 and in the central and northern parts of the Valley in 2002. While the program has been relatively successful in reducing codling moth populations, some damage

is still seen every year – and it is expensive. The sterile release program has a full time staff of 17 and 70 seasonal staff.

Oxitec indicates that the release of self-limiting diamondback moth in the U.S. is a long way off. The approval of the release of A. aegypti mosquitoes came after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and seven government agencies in Florida approved an Experimental Use Permit, following a regulatory assessment that included more than 70 scientific and technical documents, 4,500 pages of material and 25 commissioned scientific studies.

Prairie canola growers could see incidental benefits if the selflimiting diamondback moth be approved and implemented in the U.S., like reduced U.S. populations and fewer migrant moths. Since the bulk of Canada’s diamondback moths come from the Pacific Northwest, Texas and northern Mexico, reduced populations in these source areas could reduce pressures for Brassica crops.

A pupa and larva of diamondback moth on a canola leaf.

HARNESSING SILICON’S STRESS-BUSTING POWER

Research to optimize silicon use in field crops.

by Carolyn King

Conflicting results and differing opinions have swirled around silicon’s role in plants for many years. But an ever-growing mountain of scientific evidence shows silicon can be effective in protecting plants against a wide variety of stresses. Field crops, of course, always face some sort of stress during the growing season. So it’s no surprise that Richard Bélanger’s diverse research on silicon includes studies with crops like soybean, wheat and canola.

For almost three decades, Bélanger, his research group at Université Laval and his collaborators have delved into the complexities of silicon’s effects on plants. This research ranges from studies that have shed light on how silicon functions within plants on a molecular level, to applied research on the use of silicon fertilizer in greenhouse, horticultural and field crop production.

Using silicon fertilizers on field crops presents some challenges, but Bélanger is hopeful. “We’re trying to develop scientific approaches to optimize silicon’s use. We want to be able to tell growers whether or not it is going to be worthwhile applying it to their crop, give them the scientific basis for that, and help them along the way,” he says.

“Because silicon can be helpful – you can reduce your pesticide use, you can increase your yield through reduction of the losses incurred by different stresses. Under the right conditions, silicon works very well, but there are a lot of factors that are important to understand.”

A few basics about silicon

Silicon (Si) is a very common element. The amount of silicon in a soil depends on various factors, but averages around 30 per cent in mineral soils. However, in most situations, very little of that silicon is in its plant-available form, which is silicic acid.

Furthermore, not all plant species are able to absorb the plantavailable silicon. And the degree to which a silicon-absorbing plant can benefit from silicon uptake strongly depends on the stress the plant is exposed to.

Over the years, scientists have generated numerous hypotheses to try to explain how silicon affects plants and have debated whether or not silicon should be classified as an essential nutrient for plant growth.

More recently, the cumulative results from many studies have made two things clearer.

One is that silicon can definitely alleviate the impacts of biotic stresses – such as certain plant diseases and insect pests – and abiotic stresses – like drought, flooding, excessive temperature, nutrient deficiency and nutrient toxicity.

The other is that plants growing under perfect non-stress con-

ABOVE: In this example of Bélanger’s research, wheat plants were inoculated with powdery mildew following fertilization with 1.7 millimolar silicon (Si+) or with water (Si-).

ditions do not benefit from silicon uptake. Bélanger explains that silicon helps plants to partially or completely recover from stress. But silicon does not improve a plant’s performance beyond what it would have been in a non-stress situation.

Silicon is not an essential nutrient under ideal growing conditions. But its benefits to silicon-absorbing plants in the real world – where plants are always encountering stresses – can be significant. As a result, the International Plant Nutrition Institute has classified silicon as a “beneficial substance.”

PHOTOS COURTESY OF RICHARD BÉLANGER.

Which plant species can absorb silicon?

“Scientists have known for a long time, based on empirical observations, that some plants will not absorb silicon and will have very little silicon in their tissues, while other plants will have quite a bit, and some others will be in between. But we didn’t know the reason for these differences,” Bélanger says.

“Then in 2006-07, it was discovered that silicon entering into a plant was mediated by specific transporters.” Transporters are proteins that help transport water and dissolved substances across cell membranes. Silicon transporters are permeable to silicic acid.

To be able to take up and accumulate silicon, a plant must have two types of silicon transporters. “One type, an influx transporter, takes silicon in the form of silicic acid from the soil solution and brings it into the plant. Then the other type of transporter, an efflux transporter, sends the silicon into the xylem to be translocated into the leaves and other plant tissues, where it will deposit as silica,” he explains.

“Plant species that have these transporters will take up and accumulate silicon. Then, depending on other features that are not completely understood right now, some of these silicon-absorbing plants will accumulate more silicon than others.” Plant species that lack these two transporters will contain only very small amounts of silicon.

Most grasses, including crops like rice, wheat, barley and corn, have the two silicon transporters. Some broadleaf plant species, such as soybean, also have these transporters. Bélanger notes, “Rice is probably the best commercial example of a plant that has very active and very strong silicon transporters.” For example, rice has around four per cent silicon content in its leaves, and soybean has about two per cent.

“On the other hand, there are plant families that do not absorb silicon because they lack these silicon transporters. The best

examples are probably the Brassicaceae, such as canola and mustard, and the Solanaceae, such as tomato, tobacco and potato . . . If you measure silicon in a canola plant, you will find a background level, maybe 0.2 per cent, but in essence these plants don’t accumulate silicon.”

Bélanger and his group have done quite a bit of research to increase scientific understanding of silicon uptake in plants. For example, in a study with soybean, they showed that it is the plant’s rootstock – and not transpiration from the leaves – that drives silicon levels in plant tissues.

They have also done applied research on silicon uptake in soybean and other plants. For instance, they evaluated the effectiveness of different silicon fertilizers on soybean under different stress conditions.

As well, they screened more than 1,000 soybean lines and identified the very few lines that are exceptionally good at absorbing silicon. At present, no commercial soybean lines have this high silicon absorption trait. However, Bélanger and his group have created DNA markers to make it much easier for breeders to develop lines with the trait, so, perhaps one day soon, Canadian growers will have high-silicon soybean varieties with an enhanced ability to cope with biotic and abiotic stress.

Which diseases are controlled?

Bélanger explains that the scientific community has also been making headway in recent years regarding exactly how silicon uptake controls plant pathogens.

“Scientists have known for some time that silicon seems to work best against pathogens that are biotrophs or hemibiotrophs. These types of pathogens have an interaction with the plant where they do not aggressively kill the plant; instead they keep it alive so they can establish some kind of a life cycle in the living plant and

Bélanger’s group inoculated hydroponically grown soybean plants with Phytophthora sojae and applied a nutrient solution with (Si+) or without (Si-) 1.7 millimolar silicon.

derive benefits from it,” he notes.

“This type of pathogen-plant interaction depends on the pathogen’s release of what we call effectors. Usually biotrophs and hemibiotrophs are very specific to a particular host plant species because the interaction is based on the recognition between a specific effector and a specific plant receptor. For example, there are many kinds of powdery mildews, and almost every powdery mildew is specific to a particular plant species. So wheat powdery mildew will not attack barley or cucumber or rose, and vice versa.”

The molecules involved in this chemical dialogue between the pathogen’s effector and the plant’s receptor flow along a pathway in the plant called the apoplast pathway. But silicon is known to deposit as silica in this pathway. Recently, Bélanger and his group have found that these silica deposits seem to hinder the release and movement of the effectors to the receptors, preventing the dialogue between them.

“It’s almost like the pathogen no longer recognizes its host,” he says.

Bélanger and his collaborators have investigated the benefits of silicon in controlling various biotrophic and hemibiotrophic diseases, such as powdery mildews in various greenhouse, horticultural and field crops, and Phytophthora root rot in soybean.

He adds, “Phytophthora sojae is a hemibiotroph pathogen, so silicon works well for controlling it. And soybean has other important diseases caused by biotrophs and hemibiotrophs. For instance, we think silicon might be effective against soybean cyst nematode [which is a biotroph].”

Could canola be made into an Si absorber?

Bélanger and his group are currently working on an intriguing project with canola. They want to see if it might be possible to add the two silicon transporters into canola and enable canola to benefit from silicon’s stress-fighting powers.

A few years ago, they conducted some related work with Arabidopsis thaliana, a small plant with a small genome in the Brassicaceae family. Like canola, Arabidopsis lacks the two silicon transporters. The researchers inserted the influx transporter from wheat into Arabidopsis and found that the modified plants could

absorb silicon and had improved disease resistance.

“We know that canola is attacked by several important diseases caused by biotrophic pathogens such as Leptosphaeria maculans [blackleg] and Plasmodiophora brassicae [clubroot]. Through discussions with SaskCanola and some producers, we felt that canola would be very interesting to study,” Bélanger says.

“If we were to transform canola with silicon transporters, could we change its intrinsic ability to accumulate silicon and therefore benefit from silicon by becoming resistant to those pathogens?”

According to Bélanger, this project is the first time that anyone has ever tried to add both silicon transporters into a plant. So, this is high-risk research, but if successful, it could lead to significant benefits for canola growers. SaskCanola and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada are funding the project.

So far, Bélanger’s group has added the influx transporter into canola. This has resulted in a small increase in silicon in the transformed plants. However, the efflux transporter is a much larger and more complicated protein, and adding it is proving to be more difficult.

The researchers have tried several measures to overcome this roadblock, but nothing has worked so far. Now they are considering other possibilities such as trying to add both transporters into Arabidopsis and then coming back to canola.

Soil and fertilizer considerations

“Very few soils contain enough silicic acid to contribute to a high level of silicon in plants,” notes Bélanger.

“Sandy soils have low levels – although sand is mainly silica, it is bound and will not go into solution. Soils that are a bit more organic will have more silicic acid. Generally, depending on the amount of organic matter and the pH, soils have between 0.1 and 0.6 millimolar of silicic acid. The highest possible concentration of silicic acid in solution is 1.7 millimolar.” (Above this concentration, it polymerizes and is unavailable to the plant.)

Most of Bélanger’s silicon research focuses on plant disease considerations, but he has done some soil and fertilizer studies. “In the soils that we have tested in southern Ontario and Quebec, the silicic acid concentrations are extremely low. [We haven’t tested Prairie soils,] but we did some analysis of soils in the United States, including the Midwest, which is more comparable to the Prairies. We found a range in the Midwest, but generally the levels of plant-available silicon are decent there.”

He explains that greenhouse growers have been using silicon fertilizer in their crops for many years because it is easy to provide these crops with plant-available silicon in a solution. The solution is made from a silicate salt like potassium silicate, the solution’s concentration can be adjusted to 1.7 millimolar, and it is applied through a drip irrigation system.

“In field crops, [solid fertilizers] have been used such as wollastonite [calcium silicate] and silicate slags from industries. From the studies that we have done, it seems that the release of plant-available silicon from either the slags or wollastonite is not optimal. We have been working with a company to try to find ways to increase the release of silicic acid, but it is very challenging,” he says.

Bélanger and his group worked with strawberry growers in experiments that compared silicon in solution applied through a drip system and a soil-applied wollastonite fertilizer. “The difference was incredible. With the drip system, strawberry plants accumulated 3 per cent silicon, which is very high, close to the level found in rice. But the strawberry plants in the field with the [solid] fertilizer had 0.3 per cent silicon.”

He adds, “The person who comes up with an affordable, high-release silicon fertilizer would become a millionaire in a hurry because this is one of the limiting factors to applying silicon in field crops.”

In a high tunnel experiment, strawberry plants received a nutrient solution containing 1.7 millimolar silicon (Si+) or not (Si-) and were untreated for powdery mildew control.

Advice to field crop growers

Bélanger is concerned that some silicon fertilizer companies report the benefits of their products in ways that are confusing or unclear.

He gives one example: “To reduce stress, you need to have silicon accumulation in the plants. So I have asked the commercial people: did you measure the difference in silicon accumulation in the plants between the treated plots and the control plots? But they can’t answer that question.” Without that data, you can’t tell if the fertilizer benefit is due to silicon uptake or something else, such as the calcium in a calcium silicate product.

Another example relates to pH levels. “Potassium silicate is extremely alkaline, so once you mix it to the right concentration, the pH will be about 10 or 11. Therefore, you have to adjust the pH before you use it. But some people have claimed to show a toxic effect of silicon on a fungus by adding the solution to the Petri dish without adjusting the pH. So they are trying to grow a fungus on pH 11. Of course, the solution is fungi-toxic but it has nothing to do with the silicon.”

Bélanger emphasizes, “We want to work together with the commercial people, but we want to test their products in the lab to make sure that it is the silicon that is providing the benefit. We are trying to demystify silicon from a scientific point of view so we can give good advice to growers.”

If you are interested in trying a silicon fertilizer on your field crop, Bélanger recommends that you start by testing the product in a small plot and compare the treated and untreated crop.

“Take precise measurements of the plant-available silicon concentrations in the soil and the silicon concentrations in the plants. Then you can draw your conclusions about the benefits of the silicon application without going all out with this technology.”

Check with the soil and plant testing labs in your region to see if they offer these tests. Bélanger’s lab at Laval is specifically equipped to do the tests; for instance, his lab has X-ray fluorescence equipment that very precisely and rapidly measures the silicon concentration in leaves.

“Our ultimate goal is to provide growers with a user-friendly approach where they could gain benefits from silicon fertilization,” Bélanger says.

“Although silicon fertilizer is standard procedure in the greenhouse industry, we are not quite there yet in the field. But we have made a lot of headway in the last 30 years, and if we persevere, hopefully we will get to that point.”

DISEASE PRESSURE IN INTERCROPS GROWN UNDER ORGANIC MANAGEMENT

Impact depends on the intercrops used and associated underground fungal communities.

by Donna Fleury

Under organic production, intercropping a nitrogenfixing crop with another species is an alternative to the lack of economic returns on legume green manures. Intercropping is also known to provide disease suppression in some cropping systems. However, little is known about the potential impact of intercropping on root rot and fungal pathogens, especially in semi-arid regions.

“As part of a larger organic intercropping study, we wanted to take a closer look at the potential impacts of different intercrops on root disease development and underground fungal pathogens,” explains Myriam Fernandez, research scientist and principal investigator with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Swift Current Research and Development Centre (SCRDC) in Saskatchewan.

“In terms of crop disease research under intercrops, root diseases and underground pathogens tend to receive less attention than above-ground diseases, so we don’t have as much information as we would like. And the changes in agronomic practices, such as the move to primarily reduced tillage and away from summerfallow has also changed the complex of underground pathogens and incidence of root diseases, such as increases in the prevalence of Fusarium species.”

A two-year study was conducted in 2017 and 2018. The objective was to determine how intercropping a legume with a cereal (field pea-oat) or oilseed (lentil-yellow mustard) might impact disease development and the abundance and diversity of fungal populations colonizing below-ground tissue as compared to their respective monocrops. In 2018 and 2019, durum wheat was also seeded across all treatments to determine underground pathogen carryover and disease implications for this subsequent crop, such as Fusarium species that can cause serious diseases like Fusarium head blight (FHB), in addition to root and crown rot. The trials were conducted at AAFC Swift Current in the semi-arid region of the Prairies. The AAFC project collaborators included Prabhath Lokuruge, Lobna Abdellatif and Mike Schellenberg.

In preparation for the study, the organic field plots were seeded in the preceding year with a cocktail mixture of a legume, an oilseed and a cereal, which were incorporated at flowering using a tandem disc harrow. The study treatments consisted of the twocrop intercrop combinations as mixed rows to maximize their

ABOVE: Mustard and lentil intercrop trials under organic management at SCRDC.

interaction and promote the exchange of N between crop species, and their respective monocrops, at three different seeding ratios. The seeding rate was 25 per cent higher than recommended for this area for non-organic production. A variety of root pathogens and other fungal species present in the crops grown in different mixtures and root rot severity in each of these, compared to their respective monocrops, were identified and quantified. Although growing conditions in 2016 were much wetter than normal, very dry conditions occurred over the duration of this study.

“The results of the intercropping study showed that root rot was significantly affected by the crop treatments in both years and varied by environmental conditions and identified pathogens,” Fernandez explains. “Root rot severity was higher in 2018 than in 2017 for legumes, in both monocrops and intercrops. However, the variation among treatments was less consistent in lentil-mustard than in field pea-oat. The results also showed that neither grain yield nor biomass were affected by root rot levels. Other factors, such as abiotic stresses due to the dry growing conditions, were likely more important than root disease in both years and might have masked any impact of root rot on crop growth.”

The study also showed that the majority of the underground fungi were ubiquitous across all of the treatments. With the exception of a few fungi, all of the identified fungal species found in the monocrops were also present in their intercropping combinations. Although fungal communities were highly influenced by the crop species, they were not always affected by intercropping. Intercropping lentil with mustard resulted in lower root rot in lentil than in the monocrop, or the intercrop with the highest lentil ratio. The main lentil pathogens declined when intercropped with the highest mustard ratio, which could be due to the allelopathic potential of mustard. The mustard monocrop had the lowest root rot severity. However, root rot in pea intercropped with oat was greater than in the pea monocrop. This is likely attributed to the higher number of fungal populations, including pathogens, that were similar between these two crops than between lentil

and mustard. On the other hand, disease severity in oat was similar or higher in the monocrop than when intercropped with pea.

The FHB pathogens F. graminearum and F. culmorum, which were present at their highest levels in oat, tended to decrease in the intercrops.

“The most common fungal species isolated from affected roots of all crops were Fusarium spp., including the pathogenic species F. avenaceum, F. culmorum, F. oxysporum, and F. solani,” Fernandez notes. “Along with pathogens, other weakly pathogenic or saprophytic species were identified. Of all of the crops, mustard had the lowest levels of total Fusarium spp. We also isolated a different set of Fusarium species only from mustard, but none have been reported to be pathogenic on this crop. Given the wide host range of one of the most commonly isolated Fusarium species,

ABOVE: Intercropping trials of field pea-oat and lentil-yellow mustard under organic management at SCRDC.

RIGHT: In this intercrop combination, the oat crop provides support for the field pea to climb.

F. avenaceum, in this study, this pathogen is not likely going to be suppressed to a great extent by intercropping. We also did testing for Aphanomyces, but likely due to the dry conditions the results were negative. Unfortunately, due to the impacts of COVID, we are still processing the subsequent durum crops for pathogen isolation and identification.”

One interesting finding was that the non-legume crops provided the highest microbial diversity in the mixtures – some pathogenic and others not. Both oat and mustard had a greater proportion of indicator species not known for being pathogenic on these crops compared to legumes, whose indicator species were mostly pathogenic. The study also found that, compared to mustard, there were more indicator species in oat when intercropped than when grown as a monocrop, some of which are known for their biocontrol potential. Therefore, companion crops with allelopathic properties such as mustard could be considered when planning intercrop mixes.

“Along with potential disease suppression of intercropping, we did find some other interesting benefits,” Fernandez adds. “In both years of the study, the thousand kernel weight of oats was consistently higher in the intercrop than in the oat monoculture regardless of the seeding mix ratio. Although we don’t have the protein data analysis completed yet, this consistent higher thousand kernel weight in oat is important.

“Another benefit to the intercrop is the support that the oat crop provided for the field pea to climb. We are also interested to see the disease incidence and protein data results from the subsequent durum wheat crop once that is completed. We want to know what the impact of the carryover of pathogen inoculum is to that next crop, such as durum, particularly for diseases such as FHB, and whether or not intercropping might bring some benefits.”

Going forward, Fernandez has a new four-year study underway to continue evaluating different combinations of crops and seeding ratios, including intercropping barley with lentil and mustard with chickling vetch, in addition to cereals underseeded to clovers. Different legumes are also being compared as cover crops,

such as clover species, to see if some might be less susceptible to root rot pathogens. One objective is to hopefully find legumes that are not detrimental at increasing Fusarium pathogens or other pathogens, such as those causing Aphanomyces. This research will help to identify the factors that might affect the fungal communities for given sets of crop species grown together at different ratios and under different environmental conditions.

“Overall, our study shows benefits to intercropping, but that the impacts on crop diseases were varied between years, among pathogens, and mixture compositions,” Fernandez says. “Especially in our semi-arid environment and under the dry conditions during the study, intercropping may not necessarily suppress root diseases, depending on the component crops and the associated underground fungal communities.” Project funders were Western Grain Research Foundation, SaskWheat, SaskPulse, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, with in-kind contributions from Grain Millers, Imperial Seed and producers in the Advisory Committee on Organic Research at SCRDC-AAFC.

ABOVE: Field pea and oat intercrop trials under organic management at SCRDC.

RIGHT: Intercropping Research Program under Organic Management at SCRDC.